Chapter 1: What s the Big Idea?

Overview

It is not necessary to do extraordinary things to get extraordinary results.

Warren Buffett

Modern life is a mistake. I m not talking about the marvelous progress we have made in science, technology, and business, which has enabled us to eat better, stay younger , live longer, conquer disease, travel easily, and enjoy greater comfort than earlier generations.

It s the way we organize our personal and social lives that s a mistake. Instead of working to live, we live to work. If we had more self-confidence and the right philosophy, we could accomplish even more than we do now and enjoy our work more, yet labor for far fewer hours and conserve a larger part of our energy for our family and social lives.

This would be a major change in how we experience life. Here progress has run backwards . We used to enjoy more relaxed and balanced lives, with a more relaxed lifestyle, more free time, greater commitment to family and friends , greater social equality and fraternity, more civility to strangers, less stress and depression, less dependence on alcohol and drugs, and less addiction to money and power. We are now more conscious of ourselves and our individuality , but many of us are terrified of our new freedom. We worry far more, desperately seeking the illusion of security, which, despite our increasingly frantic striving, recedes ever further from us.

Life today divides into the fast track or the slow track. Both are less agreeable than the broad track of yesteryear. For many the slow track means economic insecurity: low earnings, low social standing, anxiety about unemployment, and missing out on the increasing material delights enjoyed by those on the fast track. But the fast track is not without its hazards. For many it means a single-minded obsession with getting ahead, total commitment to the job at the expense of personal relationships, and a frenzied lifestyle where work takes precedence over everything else. The fast track, too, brings anxiety and poverty, though in this case it s poverty of time and love rather than money.

If this analysis of the material advantages and personal disadvantages of modern life strikes a chord, I ve great news. If we accept that modern life works at the material, scientific, and technological level, but often screws up our personal lives, I can announce that there s a novel way out of this box.

I am referring to the 80/20 principle, the observation that roughly 80 percent of results stem from 20 percent or fewer of causes. Later in this chapter I ll explain how the principle works and give many fresh examples. For the moment, let me just say that whereas the 80/20 principle has been used successfully in business and economics and has driven progress throughout the modern world, it has not yet been applied, on anything like the same scale, to the lives of individuals. If it were so applied, we could enjoy life much more, work less, and achieve more.

In reality, the best way to achieve more is to do less . Less is more when we concentrate on the few things that are truly important, not the least of which is happiness for ourselves and our loved ones.

What is this life, if full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

William Henry Davies

I ll explain how and why using the 80/20 principle can cause a fundamental change in the way we approach life in Chapters 2 and 3. But I mustn t run ahead of myself . First, let me introduce you properly to the 80/20 principle, one of the most mind-blowing, far-reaching, and surprising discoveries of the past 200 years .

If we took 100 people and divided them into a team of 80 and a team of 20, we d expect the team of 80 to achieve four times as much. And if we randomly selected the people, something like that would probably happen.

Yet imagine a wonky world,

where the 20 people achieve

more results

than the other 80.

Make the wonky world even stranger. Imagine that not only do the 20 people achieve more than the 80, they achieve four times more .

This is exactly the wrong way round. We would expect the 80 people to achieve four times more than the 20. Now, in this curious and lopsided world, we imagine the reverse: the 20 people somehow manage to get four times the results of the other 80.

Impossible? Unlikely? Surely this wonky world, though not totally unthinkable, must be very rare.

What if one day we discovered that far from being unusual, the wonky world was actually typical ” that the world routinely divides into a few very powerful influences and the mass of totally unimportant ones. Wouldn t this turn our whole view of life upside down?

This is what happens when we discover the 80/20 principle. We find that the top 20 percent of people, natural forces, economic inputs, or any other causes we can measure typically lead to about 80 percent of results, outputs, or effects.

Counting the top cities in England, I found that the largest 53 cities had 25,793,036 people living in them, and next largest 210 cities or towns had 6,539,772. This is a terrifyingly precise 80/20 relationship:20.2 percent of the cities have 79.8 percent of the people. [1] It s worth spelling out the calculation:

-

53 out of 263 cities = 20.2%

-

25,793,036 out of 32,332,808 people = 79.8%.

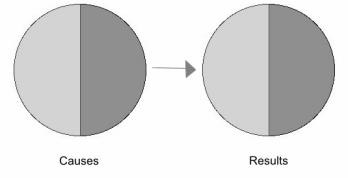

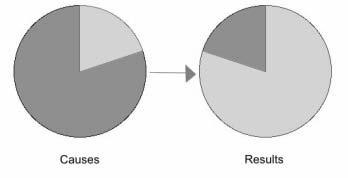

The power of the 80/20 principle lies in the fact that it is counter-intuitive , it s not what we expect. We seem to be programmed ” perhaps by our liberal culture or by an innate sense of fairness ” to expect the picture shown in Figure 1, where causes and results are balanced roughly equally: Instead, what we get is something totally different, more like Figure 2:

Figure 1: Causes and results: What we expect

Figure 2: Causes and results: What really happens

Here are some other illustrations:

-

Five people sit down to play poker. It s likely that one of them ” 20 percent ” will walk away with at least 80 percent of the stakes.

-

In any large retail store, 20 percent of the sales staff will make more than 80 percent of the dollar value of sales.

-

Studies consistently show that 20 percent of customers lead to more than 80 percent of profits for any particular firm. For example, Toronto-based Royal Bank of Canada recently worked out how much profit each of its customers provided. It was staggered to learn that 17 percent of customers yielded 93 percent of profits.

-

Fewer than 20 percent of media stars hog more than 80 percent of the limelight, and more than 80 percent of books sold come from 20 percent of authors.

-

More than 80 percent of scientific breakthroughs come from fewer than 20 percent of scientists. In every age, it is the celebrated few scientists who make the vast majority of discoveries.

-

Crime statistics repeatedly show that about 20 percent of thieves make off with 80 percent of the loot.

| |

The latest craze for single people in New York and London ” though it may have fizzled out by the time you read this ” is speed dating.

It works like this. Put around 20 “40 people in a room. The women sit down at tables and the men move from seat to seat. Each couple has between three and five minutes to talk before the man moves on to the next woman . Everyone has a unique number on a badge and you make a note of the number of anyone you d like to go on a proper date with. The organizers collect the notes at the end of the evening and match up pairs who ve liked each other. The next day they email the matches with names and contact details.

A major speed dating operator in the US confirms that most dates go to relatively few participants . At least 75 percent of the interest goes to about 25 percent of the people, he comments. Naturally they tend to be the most attractive people, but it s also true that about half of the guys who do well had been to speed dating before, and so were more confident about it.

It seems that to get a large number of dates, it s a good idea to attend at least two speed dating events.

| |

Note that 80/20 is simply shorthand for a very lopsided relationship between causes and results. The numbers don t have to add up to 100. In some cases, 30 percent of causes may lead to 70 percent of results. Other examples may show a 70/20 relationship: 20 percent of causes lead to 70 percent of results. Or the split may be 80/10, or 90/10, or even 99/1.

We often find an even more exaggerated picture than 80/20 where far fewer than 20 percent of people or causes, in some cases as little as 1 percent or less, lead to at least 80 percent of results. Here are some very wonky cases:

-

Bet fair, the world s leading betting exchange, where individuals take bets with other individuals, says that 90 percent of the money staked comes from 10 percent of its clients .

-

In Indonesia in 1985, Chinese residents comprised less than 3 percent of the population, but owned 70 percent of the wealth. [2] Similarly, the Chinese are only a third of Malaysia s population, yet own 95 percent of its wealth. [3] In Mauritius, French families make up only 5 percent of the population but own 90 percent of the wealth.

-

Out of 6,700 languages, 100 ” the top 1.5 percent ” are used by 90 percent of the world s people.

-

In a famous experiment, psychologist Stanley Milgram randomly selected 160 citizens of Omaha, Nebraska and asked them to send a package to a Boston stockbroker, but not directly. They had to send the package to someone they knew personally , who then had to pass it on to another personal contact who they thought might know someone who knew someone close to the stockbroker, and so on. Most of the packages reached the stockbroker within six steps, leading to the idea of six degrees of separation. But the point for us is that more than half the packages that made it to the stock broker came through only three well-connected individuals in Boston. Those three people were more important, in getting the desired result, than all the other inhabitants of Boston. [4]

-

Epidemics are caused by a tiny proportion of cases, which then have an effect out of all proportion to their numbers. For instance, in an outbreak of gonorrhea in Colorado Springs, neighborhoods comprising just 6 percent of the city s population accounted for 50 percent of cases. Investigation revealed that 168 people, who met in 6 bars, caused the whole epidemic . Less than 1 percent of the population of Colorado Springs was therefore responsible for 100 percent of the disease. [5]

-

Americans comprise less than 5 per cent of the world s population, yet consume 50 percent of its cocaine.

-

Much more than 80 percent of wealth created from new businesses comes from fewer than 20 percent of people who start them. Probably only 1 percent of new ventures in the past 30 years ” including Microsoft, which is worth over $200 billion ” account for 80 percent of the value created. Similarly, 1 percent of entrepreneurs ” notably Bill Gates, who is worth more than $30 billion ” make more than 80 percent of the money from new enterprises .

-

Historical files reveal that police spies in Europe were aware of several thousand professional revolutionaries between 1847 and 1917. Yet only one of them ” Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, who called himself Lenin ” actually caused a lasting revolution. Thus 1 revolutionary out of more than 3,000 ” 0.03 per cent of revolutionaries ” precipitated 100 percent of successful revolutions between those dates. Though this is an extreme example, history is full of cases where a tiny minor ity of players have diverted its whole course.

To be sure, the 20 percent or fewer of people who cause 80 percent or more of results ” whether good or bad ” are not randomly selected. They are not typical. They are interesting because they produce results that are at least 10 or 20 times greater than those produced by other people. As the high performers are not 10 or 20 times more intelligent than other people, it is the methods and resources they use that are unusually powerful.

[1] Data from the census on April 21, 1991 relating to England alone (not including the rest of the United Kingdom) from the website www.citypopulation.de.

[2] The Economist , 27 November 1993, p. 33.

[3] The Economist , 17 July 1993, p. 61.

[4] Stanley Milgram (1967) The small-world problem, Psychology Today , Vol. 2, pp. 60 “67.

[5] Malcolm Gladwell (2000) The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference , Boston: Little, Brown.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 86