Managing Service Delivery

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

The services delivered by IT to its customers across the enterprise have evolved over time and are in a constant state of flux as both the business needs of the organization and its underlying enabling information technologies evolve. [5] Given this ever-changing landscape and the general inadequacies of the typical lines of communication between IT teams and their customers, much of what is expected from IT is left unsaid and assumed. This is a dangerous situation, inevitably leading to misunderstandings and strained relations all around. The whole point of service level management is for IT to identify customer requirements clearly and proactively, to define IT services in light of those requirements, and to articulate performance metrics (i.e., service levels) governing service delivery. Then, the information technology organization should regularly measure and report on IT's performance, working to reinforce the value proposition of IT to its customers.

In taking these steps, IT management will provide its customers with a comprehensive understanding of the ongoing services delivered by the IT organization. Furthermore, service level management establishes a routine for the capture of new service requirements, for the measurement and assessment of current service delivery, and for alerting the customer to emerging IT-enabled business opportunities. In so doing, IT service delivery management will ensure that IT resources are focused on delivering the highest value to the customer and that the customer appreciates the benefits of the products and services so delivered. The guiding principles behind such a process may be summarized as follows:

-

Comprehensive — the process must encompass all business relationships and the products and services delivered by IT to its customers

-

Rational — the process should follow widely accepted standards of business and professional best practice, including standard system development life cycle (SDLC) methodologies

-

Easily understood — the process must be streamlined, uncomplicated, and simple, hence easily accessible to nontechnical participants in the process

-

Fair — through this process, the customer will understand that he or she pays for the actual product or service as delivered; cost and service level standards should be benchmarked and then measured against other best-in-class providers

-

Easily maintained — the process should be rationalized and largely paperless, modeled each year on prior-year actuals, and subsequently adjusted to reflect changes in the business environment

-

Auditable — to win overall customer acceptance of the process, key measures must be in place and routinely employed to assess the quality of IT products, services, and processes

The components of the IT service delivery management process include the comprehensive mapping of all IT services against the enterprise communities that consume those services. It also includes service standards and performance metrics (including an explicit process for problem resolution), the establishment and assignment of IT customer relationship executives (CREs) to manage individual customer group relations, a formal SLA for each constituency, and a process for measuring and reporting on service delivery. Let us consider each of these in turn.

As a first step in engineering an IT service level management process, IT management must segment its customer base and conceptually align IT services by customer. If the information technology organization already works in a business environment where its services are billed out to recover costs, this task may be easily accomplished. Indeed, in all likelihood such an organization already has SLAs in place for each of its customer constituencies. For most enterprises, however, the IT organization has grown along with the rest of the business and without any formal contractual structure between those providing services and those being served. [6] If your enterprise falls in the latter category, begin your assessment of the situation by employing an enterprise organizational chart to map your IT service delivery against that structure. As you do, ask the following questions:

-

What IT services apply to the entire enterprise and who sponsors (i.e., pays for or owns the outcome of) these services?

-

What IT services apply only to particular business units or departments and who sponsors (i.e., pays for or owns the outcome of) these services?

-

Who are the business unit liaisons with IT concerning these services, and who are their IT organization counterparts?

-

How do the business unit and IT measure successful delivery of the services in question? How is customer satisfaction measured?

-

How does IT report its results to its customers?

-

What information technology services does IT sponsor on its own initiative, without any ownership by the business side of the house?

Obviously, the responses to these questions will vary greatly from one organization to another and may in fact vary within an organization, depending on the nature and history of working relationships between IT and the constituencies it serves. Nevertheless, it should be possible to assign every service IT performs to a particular customer group or groups, even if that group is the enterprise as a whole. Identifying an appropriate sponsor may be more difficult, but in general, the most senior executive who funds the service or is held accountable for the underlying business enabled by that service is its sponsor. If too many services are owned by your IT executive team rather than line-of-business leaders, IT may have a fundamental alignment problem. Think broadly when making your categorizations. If a service has value to the customer, some customer must own it; if no customer comes forward, why is IT delivering that service in the first place? In doing such analysis for employers and clients, the author has regularly uncovered services that the enterprise no longer requires. These services were subsequently eliminated, freeing IT resources for work of greater customer value.

In concluding this analysis, the IT team will have identified and assigned all of its services (nondiscretionary work) to discrete stakeholder constituencies. This body of information may now serve as the basis for creating SLAs for each customer group. The purpose of the SLA is to identify, in terms that the customer will appreciate, the products and services that IT brings to that group. The purpose of the SLA, however, goes well beyond a listing of services. First and foremost, it is a tool for communicating vital information to key constituents about how they may most effectively interact with the IT organization. Typically, the document includes contact names, phone numbers, and e-mail addresses. Second, an SLA also helps shape customer expectations in two different but important ways. On the one hand, an SLA identifies customer responsibilities in dealing with IT. For example, it may spell out the right way to call in a problem ticket or a request for a system enhancement. On the other hand, it defines IT performance metrics for standard services and for the resolution of problems and customer inquiries. Last but not least, a standard SLA compiles all the services and service levels that IT has committed to deliver to that particular customer, reinforcing the value proposition between that business entity and the information technology organization.

SLAs can take on any number of forms. [7] Whatever form you chose, ensure that it is as simple and brief a document as possible. Avoid technical jargon and legalese, and be sensitive to the standard business practices of the greater enterprise within which your IT organization operates. [8] Most of all, write your SLAs from your customer's perspective, focusing on what is important to the customer. State in plain English what services the customer receives from you, the performance metrics for which IT is accountable, and what to do when things break down or go wrong. A more detailed discussion of the SLA may be found in Chapter 4. Whatever the final form of your SLA, prepare SLAs for your entire customer base at one time to ensure that, in total, they address all IT services as delivered and their associated consumption of IT resources.

Your next step is to assign a customer relationship executive (CRE) to each SLA account. The CRE serves as a primary point of contact between customer executive management and the IT organization. In this role, the CRE will meet with his or her executive sponsors for an initial review of that business unit's SLA and thereafter on a regular basis to assess IT performance against the metrics identified in the SLA. Where IT delivers a body of services that apply across the enterprise, you might consider creating a single, community SLA that applies to all and then brief addenda that list the unique systems and services pertaining to particular customer groups. Whatever the formal structure of these documents, the real benefit of the process comes from the meetings in which the CRE can reinforce the value of IT to the customer, listen to and help address IT delivery and performance problems, learn of emerging customer requirements, and share ideas about opportunities for further collaboration between the customer and IT. Within IT, the CRE will act as the advocate and liaison for, and as the accountable executive partner to, his or her assigned business unit in strategic and operational matters.

CREs must be chosen with care. They should be good listeners and communicators. For the customer in question, they must have a comprehensive understanding of what IT currently delivers and what information technology may afford. Although they need not be experts in all aspects of the business conducted by the customer, they must at least have a working knowledge of that business, its nomenclature, and the roles and responsibilities of those working in that operating unit. Among the many skills that a good CRE must possess is the ability to translate business problems into technical requirements and technical solutions into easily understood narratives that the customer can appreciate. The CRE also must be a negotiator, helping the customer to appreciate the breadth of that business unit's portfolio of IT services and projects, within the limitations of the resources available to serve those needs. At some times, such conversations may require that the customer choose among existing options, and at others, defer a request for IT services to a more opportune occasion.

IT customers will appreciate immediately the value of the CRE, because this role offers them a single channel for addressing their strategic and tactical IT needs. Over time, this arrangement may lead to abuses, such as customers who approach the CRE with problems more appropriately directed to the IT help desk or an IT line service provider. When this occurs, the CRE should take the information, indicate that he or she will forward it to the proper person in IT, and suggest that the customer go directly to the appropriate IT party in the future. Here, the CRE functions as a facilitator of best practices in the working relationship between a given customer group and the information technology organization. He or she can also note weaknesses in IT procedures and work behind the scenes with IT colleagues on process improvements. The greatest value of the CRE, however, is to act as a human link to a key IT customer constituency, managing customer expectations while keeping IT focused on the quality delivery of its commitments to that group.

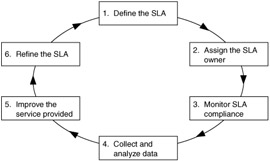

This effort is iterative: collecting and processing data, meeting with customers and IT service providers, listening, communicating, and educating. As depicted in Exhibit 3, SLA process management operates on an annual calendar. The CRE reports to the customer on a monthly or more frequent basis and brings back data to refine and clarify existing service delivery, as well as the service objectives for the coming year.

Exhibit 3: The SLA Management Process

Again, the key to success for the CRE and the SLA process is attention to detail. Customers hate surprises. They can understand that IT will fail from time to time; after all, what technical or, for that matter, human process components do not? What matters is keeping the customer apprised of what is going on and what IT is doing to address performance difficulties. If the customer remains well informed, much of the tension between IT and those it serves will dissipate as trusting business relationships mature. By respecting the cycle of service delivery and by communicating regularly and with full disclosure, the overall process will pay off for you and your IT team.

The service level management process will ensure the proper alignment between customer needs and expectations on the one hand, and IT resources on the other. The process clearly defines roles and responsibilities, leaves little unsaid, and keeps the doors of communication and understanding open on both sides of IT service delivery. From the standpoint of IT leadership, the SLA process offers the added benefit of maintaining a current listing of IT service commitments, thus filling in the nondiscretionary layers of IT's internal economy model. Whatever resources remain may be devoted to project work and applied research into new, IT-enabled business opportunities. Bear in mind that this is a dynamic model. As the base of embedded IT services grows, a greater portion of IT resources will fall within the sphere of nondiscretionary activity, limiting project work. The only way to break free from these circumstances is to curtail existing services or to broaden the overall base of IT resources.

In any event, the service level management process will provide most of the information that business and IT leaders need to make informed decisions concerning the scope, quality, and value of day-to-day IT service delivery. Chapter 4 contains a more detailed consideration of service delivery management tools and techniques. With the service delivery side of the house clarified, let us now turn to the discretionary side of IT investment: project delivery. IT project work calls for a body of management practices complementary to those on the service side if such efforts are to succeed.

[5]For a particularly comprehensive consideration of this subject, see Rick Sturm, Wayne Morris, and Mary Jander, Foundations of Service Level Management (Indianapolis, IN: SAMS, 2000).

[6]Unless the enterprise's leadership has chosen to operate IT as a separate entity with its own profit-and-loss statement, the author would recommend against the establishment of a charge-back or transfer pricing system between IT and its customers. Instead, the author recommends that the business and IT leaderships agree jointly on the organization's overall IT funding level and that IT manage those funds in line with the service level and project commitment management processes and performance metrics outlined in this book.

[7]See Sturm, Morris, and Jander, pp. 189–196.

[8]For example, an SLA that resembles a formal business contract is appropriate and necessary for a multi-operating unit enterprise in which each line of business runs on its own P&L and must be charged back for the IT services that it consumes. On the other hand, such an SLA would only confuse and frustrate the executives of an institution of higher education, who are unaccustomed to formal and rigorous modes of business communication and operate more collegially in an informal context of mutual trust and respect.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 132