Protocol Characteristics

The first part of this chapter discusses the basic characteristics found in the world's available transport protocols. This information is meant to provide a bit of background on the type of behavior that protocols adhere to as well as to inform you, the programmer, of how a protocol will behave in an application.

Message-Oriented

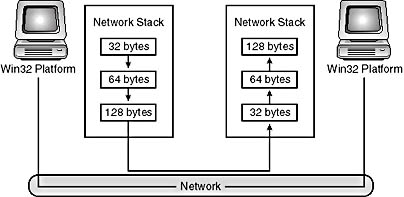

A protocol is said to be message-oriented if for each discrete write command it transmits those and only those bytes as a single message on the network. This also means that when the receiver requests data, the data returned is a discrete message written by the sender. The receiver will not get more than one message. In Figure 5-1, for example, the workstation on the left submits messages of 128, 64, and 32 bytes destined for the workstation on the right. The receiving workstation issues three read commands with a 256-byte buffer. Each call in succession returns 128, 64, and 32 bytes. The first call to read does not return all three packets, even if all the packets have been received. This logic is known as preserving message boundaries and is often desired when structured data is exchanged. A network game is a good example of preserving message boundaries. Each player sends all other players a packet with positional information. The code behind such communication is simple: one player requests a packet of data, and that player gets exactly one packet of positional information from another player in the game.

Figure 5-1. Datagram services

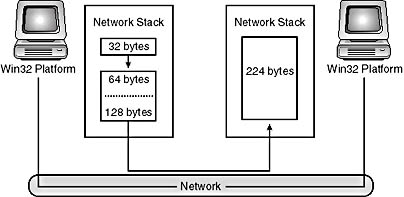

A protocol that does not preserve these message boundaries is often referred to as a stream-based protocol. Be aware that the term "stream-based" is often loosely applied to imply additional characteristics. Stream service is defined as the transmitting of data in a continual process: the receiver reads as much data as is available with no respect to message boundaries. For the sender, this means that the system is allowed to break up the original message into pieces or lump several messages together to form a bigger packet of data. On the receiving end, the network stack reads data as it arrives and buffers it for the process. When the process requests an amount of data, the system returns as much data as possible without overflowing the buffer supplied by the client call. In Figure 5-2, the sender submits packets of 128, 64, and 32 bytes; however, the local system stack is free to gather the data into larger packets. In this case, the second two packets are transmitted together. The decision to lump discrete packets of data together is based on a number of factors, such as the maximum transmit unit or the Nagle algorithm. In TCP/IP, the Nagle algorithm consists of a host waiting for data to accumulate before sending it on the wire. The host will wait until it has a large enough chunk of data to send or until a predetermined amount of time elapses. When implementing the Nagle algorithm the host's peer waits a predetermined amount of time for outgoing data before sending an acknowledgement to the host so that the peer doesn't have to send a packet with only the acknowledgement. Sending many packets of a small size is inefficient and adds substantial overhead for error checking and acknowledgments.

On the receiving end, the network stack pools together all incoming data for the given process. Take a look at Figure 5-2. If the receiver performs a read with a 256-byte buffer, all 224 bytes are returned at once. If the receiver requests that only 20 bytes be read, the system returns only 20 bytes.

Figure 5-2. Stream services

Pseudo-stream

Pseudo-stream is a term often applied to a system with a message-based protocol that sends data in discrete packets, which the receiver reads and buffers in a pool so that the receiving application reads data chunks of any size. Combining the sender in Figure 5-1 with the receiver in Figure 5-2 illustrates how pseudo-streams work. The sender must send each individual packet separately, but the receiver is free to gather them. For the most part, treat pseudo-streaming as you would a normal stream-oriented protocol.

Connection-Oriented and Connectionless

A protocol usually provides either connection-oriented services or connectionless services. In connection-oriented services, a path is established between the two communicating parties before any data is exchanged. This ensures that there is a route between the two parties in addition to ensuring that both parties are alive and responding. This also means that establishing a communication channel between two participants requires a great deal of overhead. Additionally, most connection-oriented protocols guarantee delivery, further increasing overhead as additional computations are performed to verify correctness. On the other hand, a connectionless protocol makes no guarantees that the recipient is listening. A connectionless service is similar to the postal service: the sender addresses a letter to a particular person and puts it in the mail. The sender doesn't know whether the recipient is expecting to receive a letter or whether severe storms are preventing the post office from delivering the message.

Reliability and Ordering

Reliability and ordering are perhaps the most critical characteristics to be aware of when designing an application to use a particular protocol. In most cases, reliability and ordering are closely tied to whether a protocol is connectionless or connection-oriented. Reliability, or guaranteed delivery, ensures that each byte of data from the sender will reach the intended recipient unaltered. An unreliable protocol does not ensure that each byte arrives, and it makes no guarantee as to the data's integrity.

Ordering has to do with the order in which the data arrives at the recipient. A protocol that preserves ordering ensures that the recipient receives the data in the exact order it was sent. Obviously, a protocol that does not preserve order makes no such guarantees.

Reliability and ordering are closely tied to whether a protocol is connectionless or connection-oriented. In the case of connection-oriented communications, if you are already making the extra effort to establish a clear communication channel between the two participants, you usually want to guarantee data integrity and data ordering. In most cases, connection-oriented protocols do guarantee reliability. The next section discusses actual protocols and their characteristics. Note that by assuring packet ordering, you do not automatically guarantee data integrity. Of course, the great benefit of connectionless protocols is their speed: they don't bother to establish a virtual connection to the recipient. Why slow this down with error checking? This is why connectionless protocols generally don't guarantee data integrity or ordering, while connection-oriented protocols do. Why would anyone use datagrams with all these faults? Generally, connectionless protocols are an order of magnitude faster than connection-oriented communications. No checks need to be made for factors such as data integrity and acknowledgments of received data, factors that add a great deal of complexity to sending even small amounts of data. Datagrams are useful for noncritical data transfers. Datagrams are well suited for applications like the game example that we discussed earlier: each player can use datagrams to periodically send his or her positions within the game to every other player. If one client misses a packet, it quickly receives another, giving the player an appearance of seamless communication.

Graceful Close

A graceful close is associated only with connection-oriented protocols. In a graceful close, one side initiates the shutting down of a communication session and the other side still has the opportunity to read pending data on the wire or the network stack. A connection-oriented protocol that does not support graceful closes causes an immediate termination of the connection and loss of any data not read by the receiving end whenever either side closes the communication channel. In the case of TCP, each side of a connection has to perform a close to fully terminate the connection. The initiating side sends a segment (datagram) with a FIN control flag to the peer. Upon receipt, the peer sends an ACK control flag back to the initiating side to acknowledge receipt of the FIN, but the peer is still able to send more data. The FIN control flag signifies that no more data will be sent from the side originating the close. Once the peer decides it no longer needs to send data, it too issues a FIN, which the initiator acknowledges with an ACK control flag. At this point, the connection has been completely closed.

Broadcast Data

To broadcast data is to be able to send data from one workstation so that all other workstations on the local area network can receive it. This feature is available to connectionless protocols because all machines on the LAN can pick up and process a broadcast message. The drawback to using broadcast messages is that every machine has to process the message. For example, let's say the user broadcasts a message on the LAN, and the network card on each machine picks up the message and passes it up to the network stack. The stack then cycles through all network applications to see whether they should receive this message. Usually a majority of the machines on the network are not interested and simply discard the data. However, each machine still has to spend time processing the packet to see whether any applications are interested in it. Consequently, high-broadcast traffic can bog down machines on a LAN as each workstation inspects the packet. In general, routers do not propagate broadcast packets.

Multicast Data

Multicasting is the ability of one process to send data that will be received by one or more recipients. The method by which a process joins a multicast session differs depending on the underlying protocol. For example, under the IP protocol, multicasting is a modified form of broadcasting. IP multicasting requires that all hosts interested in sending or receiving data join a special group. When a process wishes to join a multicast group, a filter is added on the network card so that data bound to only that group address will be picked up by the network hardware and propagated up the network stack to the appropriate process. Video conferencing applications often use multicasting. Chapter 11 covers multicast programming from Winsock as well as other critical multicasting issues.

Quality of Service

Quality of service (QOS) is an application's ability to request certain bandwidth requirements to be dedicated for exclusive use. One good use for quality of service is real-time video streaming. In order for the receiving end of a real-time video streaming application to display a smooth, clear picture, the data being sent must fall within certain restrictions. In the past, an application would buffer data and play back frames from the buffer to maintain a smooth video. If there is a period during which data is not being received fast enough, the playback routine has a certain number of buffered frames that it can play. QOS allows bandwidth to be reserved on the network, so frames can be read off the wire within a set of guaranteed constraints. Theoretically this means that the same real-time video streaming application can use QOS and eliminate the need to buffer any frames. QOS is discussed in detail in Chapter 12.

Partial Messages

Partial messages apply only to message-oriented protocols. Let's say an application wants to receive a message but the local computer has received only part of the data. This can be a common occurrence, especially if the sending computer is transmitting large messages. The local machine might not have enough resources free to contain the whole message. In reality, most message-oriented protocols impose a reasonable limit on the maximum size of a datagram, so this particular event is not encountered often. However, most datagram protocols support messages of a size large enough to require being broken up into a number of smaller chunks for transmission on the physical medium. Thus the possibility exists that when a user's application requests to read a message, the user's system might have received only a portion of the message. If the protocol supports partial messages, the reader is notified that the data being returned is only a part of the whole message. If the protocol does not support partial messages, the underlying network stack holds onto the pieces until the whole message arrives. If for some reason the whole message does not arrive, most unreliable protocols that lack support for partial messages will simply discard the incomplete datagram.

Routing Considerations

One important consideration is whether a protocol is routable. If a protocol is routable, a successful communication path can be set up (either a virtual connection-oriented circuit or a data path for datagram communication) between two workstations, no matter what network hardware lies between them. For example, machine A is on a separate subnet from machine B. A router linking the two subnets separates the two machines. A routable protocol realizes that machine B is not on the same subnet as machine A; therefore, it directs the packet to the router, which decides how to best forward the data so that it reaches machine B. A nonroutable protocol is not able to make such provisions: the router drops any packets of nonroutable protocols that it receives. The router does not forward a packet from a nonroutable protocol even if the packet's intended destination is on the connected subnet. NetBEUI is the only protocol supported by Win32 platforms that is not capable of being routed.

Other Characteristics

Each protocol supported on Win32 platforms presents characteristics that are specialized or unique. Also, a myriad of other protocol characteristics, such as byte ordering and maximum transmission size, can be used to describe every protocol available on networks today. Not all of those characteristics are necessarily critical to writing a successful Winsock application. Winsock 2 provides a facility to enumerate each available protocol provider and query its characteristics. The third section of this chapter explains this function and presents a code sample.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 159

- A View on Knowledge Management: Utilizing a Balanced Scorecard Methodology for Analyzing Knowledge Metrics

- Measuring ROI in E-Commerce Applications: Analysis to Action

- Technical Issues Related to IT Governance Tactics: Product Metrics, Measurements and Process Control

- Governance in IT Outsourcing Partnerships

- The Evolution of IT Governance at NB Power