Moving Beyond Compliance to Self-Sustaining Continuous Improvement

Compliance, of course, is simply the first step, and many would argue, only fleeting if more fundamental issues are not addressed. It is one thing not to employ child labor, or to provide on-site washing facilities, but it is only when the labor force is well-trained, safe, and adequately compensated that any sustainable improvements can be assured. But to truly move from minimum compliance to higher levels of productivity and continuous improvement requires something more than just imposing international codes of conduct. This level of productivity improvement is most likely, not when it is imposed by an outside code, but when the management and employees of the supplier themselves take responsibility for continuously improving working conditions, environmental policies, and productivity methods . This is just as true for a manufacturing site in Indonesia, India, or China as it is in Toledo, Birmingham, or Lille. This usually means helping the supplier to develop other, more advanced management techniques, such as creating a program for worker training and development or providing incentives for productivity improvement.

Both H&M and Chiquita have gone even further.

| |

The following text is directly quoted from Ethical Performance, Autumn 2001. See source note below.

Chiquita, which produces a quarter of Latin American bananas, has spent eight years working to ensure all its banana farms in Latin America meet labour and environmental standards that are independently verified by an international non-governmental organization.

In the often-troubled Latin American banana industry, where labour unions have been seeking change for more than a decade , one company has made a bold ” and so far lone ” move to become a model of best practice on workplace conditions and environmental management.

Last autumn, after eight years of hard work, the fresh food group Chiquita met an independently verified social and environmental standard for the 127 banana farms it owns in Latin America. The standard is run by the Rainforest Alliance, an international non-profit organization responsible for certifying farms under its Better Banana Project (BBP).

Chiquita is the only global banana company to have undertaken and met the BBP s standards, which are the centrepiece of a rapidly expanding corporate social responsibility programme. Chiquita outlined many of its initiatives in its first Corporate Responsibility Report published in September 2001.

The publication of this report sets a high standard for the whole industry. The same can be said for the groundbreaking recent agreement with unions in Latin America that commits Chiquita to respect the core labour conventions of the International Labour Organization and establishes mechanisms for regular consultation, and for oversight of compliance.

The Rainforest Alliance began the BBP in 1991, around the same time that Chiquita, which produces roughly 25 per cent of the world s bananas, began looking for just such an authoritative environmental standard to improve life for its employees and safeguard the environment.

Jeff Zalla, corporate responsibility officer at Chiquita, says senior management at the company had reached the conclusion ” through education and increased awareness rather than any reputational catastrophe ” that things needed to change. We wanted to improve our social and environmental performance in an authentic way and BBP was the most rigorous standard, he says.

We felt we had a particular responsibility as an agricultural producer in developing countries to do something ” and as a brand to lead our industry. As a result, Chiquita and the Rainforest Alliance began talks, that, in 1992, led the company to test out the idea of trying to meet the BBP standards.

The standards, which are detailed in a 19-page document, cover a wide range of topics, from workers rights to the storage of packaging material on plantations. When two pilot farms in Costa Rica achieved certification, senior management decided to extend the work. The first batch of Chiquita farms was certified in 1994, and the long haul to 100 per cent certification began.

Since then Chiquita has, among other things, made efforts to reduce pesticide use, reforested more than 1000 hectares with native trees and put 525ha of land under protection. On workers welfare, certification has helped Chiquita employees attain a much higher standard of living than other agricultural workers in the countries where the company operates.

Employees in Costa Rica, for instance, now earn more than oneanda-half times the standard minimum wage. They also have improved training, housing, health benefits, education, and transport. All company workers have the right to associate freely , and Chiquita has almost as many union workers as all other banana companies in Latin America combined.

The Chiquita farms are certified only after frequent visits by trained independent inspectors, who are brought in from a network of conservation organizations affiliated to the Rainforest Alliance. They verify that the changes needed to meet the standards are being made, and that farms have introduced measures to improve the quality of life of workers, reduce agrochemical use and increase water quality and wildlife habitat.

All farms owned by the company in Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama, cultivating more than 28,400ha, have now been certified. A further 30 per cent of independent farms selling bananas to the company have also been certified, and the company is keen to encourage the remaining 70 per cent of independent producers to follow suit. Together, according to the Rainforest Alliance, total production from Chiquita s certified owned and independent producer farms, amounts to almost 15 per cent of banana exports from Latin America.

Complying with the BBP has cost the group more than $20 million in capital expenditure, along with millions of dollars in annual operating costs, but Tensie Whelan, executive director of the Rainforest Alliance, says the company s extraordinary efforts to reach compliance are leading the way for the rest of the industry. George Jaksch, Chiquita s quality director in Europe also judges the money has been well-spent.

What we have done in our tropical division is hugely important for our European business, Jaksch says. Many of our retail customers would not be doing business with us unless we had a really thorough and deeply rooted programme like this.

Zalla says the BBP has helped align the whole organization behind a clear performance standard. He adds: We see a lot more discipline throughout the company as a result of what we have done under the BBP. It s hard to put a cost figure on the improvements, but they are very real in terms of workplace conduct and productivity. There have also been real cost savings through measures such as reducing the use of pesticides.

Even without those benefits, Zalla says Chiquita would have done what it did because we are committed to doing the right thing. He adds: In a country such as Colombia there are huge social problems in the areas where we produce bananas. It makes a real difference that the company has a programme of this kind. It creates a workplace where people can feel valued and work safely.

Source: Ethical Performance, Autumn 2001 at www.ethicalperformance.com/best_practice/archive/1001/case_studies/chiquita.html.

| |

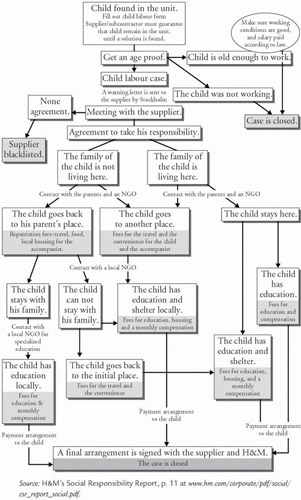

H&M, the European clothing retailers provide another good example of an innovative program that helps to deal with the issue of child labor. Rather than severing contact with a supplier that is found guilty of employing child labor, H&M require the supplier to pay for the child s education costs until he or she is old enough to begin to work legally.

When a child is found, H&M executes an action plan together with the child s family and the supplier in order to get the child back in school, says H&M. When seeking a solution for the child, H&M makes sure that the measures taken are in the child s best interest. This is our primary focus. H&M demands the supplier pays both for school and retained salary. H&M stays in contact with the supplier, the family, and the school to make sure that the child continues his education. If this is not cared for, the children often are off to another job, trying to earn double incomes. [10 ] (See Figure 15-1.)

It is a truism of business strategy that sustainable change does not result-from adapting systems, procedures and processes, says Michael Allen from the Global Alliance, but requires a shift in an organization s culture ” in the ethos, attitudes and behavior of its people. This may seem abstract in relation to improving workplace conditions in an Asian apparel factory or a Central American plantation.

Our experience, says Allen, based on confidentially consulting over 10,000 workers and managers in several Asian countries, suggests that investing in employee training, services and development ” including critical health, workplace and life skills ” can be a catalyst for changing workplace culture and cultivating local ownership of workplace improvement. [11 ]

One method for deciding the level of effort and strategic importance of the company s efforts in this area is simply to define how the company wishes to be perceived by stakeholders by using the following scale:

-

Minimum effort: Indifferent to ethical or legal issues.

-

Below the industry average, or unable to accurately judge ethical or environmental standards.

-

Complies with all laws.

-

Has made the decision to create an ethical framework and to actively promote social and environmental policies.

-

Industry leadership.

One of the most innovative companies in the area of CSR and supplier management is British Telecom, which, with 28 million fixed phone lines and another 7.5 million mobile phone customers, already has in place a strong set of environmental programs governing their emissions, energy usage, and disposal of waste and used materials. As part of a comprehensive environmental management system they have implemented ISO 14001 in all of their UK operations. Their recycling program now recycles nearly 1/3 of the company s total waste, reducing waste to landfill by 5.6 percent. This focus on waste recycling saves them more than $4 million each year on landfill tax alone. At the same time they have focused on improving their fleet size and efficiency, and in the last decade have reduced company energy usage by 23 percent, saving them more than $6 million during the same period. [12 ]

Figure 15-1: Overview of H&M Actions in Case of Suspected Child Labor Developed by Our CSR-Team in India (similar procedures are followed in other countries)

Source: H & M s Social Responsibility Report, p. 11 at www.hm.com/corporate/pdf/social/csr_report_social.pdf.

Equally important, BT have put together a broad program for implementing high standards within its extended supply chain, and have issued a set of guiding principles that can be valuable for any company contemplating adopting standards and developing a supplier program. These guiding principles provide a strong framework for their ethical supply chain program.

Principle 1: Working Together

BT will:

Work collaboratively with suppliers in pursuit of these standards.

Guide relationships by the principle of continuous improvement.

Welcome rather than penalise suppliers identifying activities that fall below these standards (undertaken by themselves or sub-contractors) and who agree to pursue our aspirations.

Review and, where appropriate, revise these principles in the light of experience.

Consider a similar ethical trading standard as a reasonable alternative where suppliers are already working towards this alternative.

Not hold a supplier to a higher standard than BT s own policy on these issues.

Principle 2: Making a Difference

BT and it suppliers should:

Use a risk-based approach to the implementation of these standards.

Focus attention on those parts of the supply chain where the risk of not meeting these standards is highest and where the maximum difference can be made with resources available.

BT s suppliers should:

Be prepared to share with BT the basis of their approach with regard to the above.

Principle 3: Public Reporting

Report publicly our performance and practices with regard to the implementation of GS18 Sourcing with Human Dignity .

Principle 4: Awareness Raising and Training

BT and its suppliers should:

Ensure that all relevant people are provided with appropriate training and guidelines to implement the standards.

Principle 5: Monitoring and Independent Verification

BT will:

Recognise that the implementation of these standards may be assessed through monitoring and independent verification, and that these methods will be developed as our understanding grows.

BT s suppliers should:

Provide BT or its representatives with reasonable access to all relevant information and premises and cooperate in any GS18 Sourcing with Human Dignity assessment ” using reasonable endeavors to ensure that subcontractors do the same.

Use reasonable endeavours to provide workers covered by the standards with a confidential means to report to the supplier failure to observe the standards.

Principle 6: Continuous Improvement

BT and its suppliers should:

Apply a continuous improvement approach in agreeing schedules for improvement plans with suppliers not meeting these standards.

Base improvement plans on individual case circumstances.

Not use this project to prevent suppliers from exceeding these standards.

BT will:

Following an escalation to BT s Chief Procurement Officer, consider terminating any business relationship with the supplier concerned where serious shortfalls of these standards persist. [13 ]

Whatever level of supplier engagement a company ultimately chooses, the SEAAR movement continues to push companies toward creating reports for their investors that reflect what policies and procedures a company has put in place in order to manage risks that might come from the workplace and environmental policies of its suppliers. Creating those sustainability reports is the final feature of an ethical supply chain framework.

[10 ] H&M Social Responsibility Report, op. cit., p. 10.

[11 ] Michael Allen, Analysis: Increasing Standards in the Supply Chain, Ethical Corporation, October 2002, pp. 34 “ 36.

[12 ] Conference discussion with Chris Tuppen, November 2002; also Case Studies, BT: Staying online with ISO 14001, 2001 Business in the Environment, Ernst & Young.

[13 ] GS18 Sourcing With Human Dignity: A Supply Chain Initiative, British Telecom, Issue 3, September 13, 2002, pp. 4 “ 5 at http://216.239.51.100/search?q_ cache:Y2QOEfgf8nQC: www.selling2bt.com/data/working/humandignity/gs18.pdf _ ethical _ supply _ chain&hl _ en&ie _ UTF-8.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 123

- Using SQL Data Definition Language (DDL) to Create Data Tables and Other Database Objects

- Using SQL Data Manipulation Language (DML) to Insert and Manipulate Data Within SQL Tables

- Working with Functions, Parameters, and Data Types

- Working with SQL JOIN Statements and Other Multiple-table Queries

- Repairing and Maintaining MS-SQL Server Database Files

- Chapter I e-Search: A Conceptual Framework of Online Consumer Behavior

- Chapter V Consumer Complaint Behavior in the Online Environment

- Chapter VII Objective and Perceived Complexity and Their Impacts on Internet Communication

- Chapter XI User Satisfaction with Web Portals: An Empirical Study

- Chapter XVIII Web Systems Design, Litigation, and Online Consumer Behavior