Acquisition and Retention Features

Most computer and video games have only one distribution problem: how to acquire customers ”that is, how to get the customers to walk into a store and buy the box. This includes retail hybrids, as most publishers don't provide an online distribution or multiplayer support solution for customers; they depend on the players to do that for themselves , or for one of several online hybrid gaming portals such as GameSpy or The Zone to do it for them. In neither case does online in-game support become a factor. Hybrids today are a product, but they are not yet a full service in most aspects. Online games in the persistent world (PW) category, being both a product and a service, have a unique problem: They not only have to acquire customers, but they also have to retain them. If a subscription fee is involved, the retention factors have to work for a minimum of some months or, preferably, years . It makes plain sense, then, to know just who it is you want to play and pay for the game and what features those people want that will keep them coming back month after month. If you accept the market demographic niche definitions found in Chapter 1, "The Market," you have a pretty good idea of who will pay a subscription fee, who might pay a fee, and who you're going to have a devil of a time getting to pay you a penny. That puts you halfway home; now you must nail down the details. Before we can really start listing the features, we have to know who we want to, and/or is likely to, play the game after launch. Prioritizing: Who Are We Designing This Game For?Design/development teams proposing expensive PW projects tend to engage in a bit of (mostly) unintentional obfuscation toward executives; the teams treat the PW market as a solid whole and fail to mention that there are identifiable sub-populations within the genre . In effect, they engage in lying by omission because they either don't really understand the different sub-populations' motivations or they just assume the executives won't understand the difference between someone whose primary play motivation is hanging out and chatting and one who is going single-mindedly to gather every cool possession in the game. Some experienced online game designers don't want to admit to the " suits " that there might be a significant percentage of players (25%, in fact) who care as much or more for socializing than about the game or its mechanics. They might put a limit on all of the neat stuff the designers want to load into the game in favor of more chat tools, for instance, and where's the coolness in designing chat tools? There is nothing wrong with building a PW game that appeals only to one or two of the four main player niches ; for example, EQ appeals directly to the achiever class of gamer, with a nod or two to the socializers , and one could hardly call that game unsuccessful . To appeal to the broadest possible cross-section of potential subscribers, however, a PW should contain elements that appeal directly to the four main Bartle player types. Before that can happen, everyone ”from executives paying the bills to the most junior designer ”needs to agree on just what those types are. Thankfully, a pretty good definition and model set exists, written by the good Dr. Bartle. The Bartle Player TypesDr. Richard Bartle was the co-creator of the first MUD in 1978. Over the years, as MUDs proliferated on university mainframes and eventually as commercial products, he noticed certain types of common play behavior in MUDs and made the first attempt to categorize those behaviors. The categories he defined were achiever, explorer, socializer, and killer, and he explained the behavior patterns in an article titled "Hearts, Clubs, Diamonds, Spades: Players Who Suit Muds." [2] The article was first written in 1995 and gained widespread recognition quickly. Over the years, Dr. Bartle has periodically edited and revised the article to keep it current.

Here is how Bartle described what he saw:

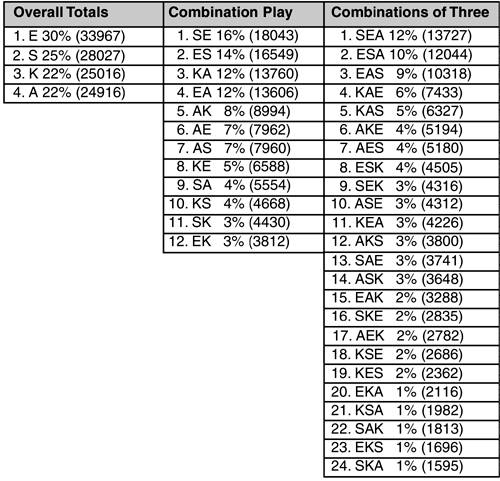

This was the first attempt to define general player and gameplay types in a virtual world, and these motivations still hold up well in today's market, where games with 20,000 “100,000 simultaneous players are no longer unknown or even rare. These types more than adequately explain the gross motivations of the general player base and provide a good framework from which to start designing a massively multiplayer (MMP) game world. Moreover, players rarely exhibit just one form of play behavior; they tend to mix and match styles and change behaviors over time. Several years ago, Erwin Andreasen put up on the web a survey of questions, the answers to which would allow MUD and PW players to rate their own play styles and discover how much of their play time was as an achiever, socializer, explorer, or killer. Table 8.1 includes some of the results from the Bartle Quotient Survey [3] on the web, showing how players rate themselves in various combinations of those four general categories created by Dr. Bartle, sorted by response rates, combinations of play in the categories, and percentages of the total respondents. The responses to the survey gives you an inkling of how players see themselves and their own playing styles in PWs.

Table 8.1. Survey Results from "Measuring the Bartle Quotient"From the "Measuring the Bartle Quotient" web site, http://www.andreasen.org/bartle/, March 4, 2002 at 2:28pm EST. Abbreviations: E= explorer, S= socializer, A= achiever, and K= killer. The numbers in parentheses represent the total number of respondents scored in that percentile. The Combination Play column represents the total percentage of players scored by combination players, such as socializer/explorers (16% of the total respondents). The Combinations of Three column represents an even finer gradation of play, such as 12% of the total respondents showed elements of socializer, explorer, and achiever in play style. As of the date and time this sample was taken, there had been a total of 111,926 respondents included in this composite. Despite the fact that the survey is unscientific, it has been the experience of the authors that these percentages fairly closely match the reality of the customer base in current commercial PWs, with the exception of the "importance" of the killer class of players. The importance of that class has been overblown by a vocal minority and by PvP combat-oriented designers. For example, check out the specific survey results for the top five commercial PWs [4] in Appendix C "The Bartle Quotient Survey and Some Results," and you'll find few people rating themselves as pure killers in most games.

The takeaway from this exercise should be obvious: 55 “60% of players in both the general population and those playing for-pay games classify themselves primarily as socializers and explorers. These are people who form and join guilds and teams, spend quite a bit of time in-game chatting or engaging in social events, and wander about the world, exploring its secrets. For three of the five commercial games, 20% or fewer of the players rate themselves as killers, with 26% for UO and 25% for Dark Age of Camelot , two games that are attractive to the killer class of player due to the faction-based conflict inherent within their designs. What this says is that, even if you build a game heavily weighted toward the killer classes via PvP and faction or team/guild conflict, chances are you're going to be attractive to only 20 “25% of the total player base. The dichotomy of this is that most of the PWs that launched in 2001 or are being developed today for launch in 2002 “2003 are heavily weighted in design toward the killer class. This is likely to cause increased churn rates for the socializer and explorer classes, whom the killers look at as their intended victims by virtue of that same design. Unless you're firmly set on appealing to one player type and you're comfortable with the thought that such a design may greatly limit your subscriber total potential, the idea is to have a balanced design that appeals to a number of player niches. Features: Acquisition and Retention Over TimeFor purposes of the following discussion, we're going to assume that you want to appeal in some fashion to all four Bartle types, in an attempt to maximize the subscriber total of your game. Now that you have a general idea of the size and scope of the basic customer groups, you can take the design treatment discussed earlier and begin to match up the vision of the game with the features the players will want to have available. Exactly what those features are, however, is a matter of some controversy within the industry. Some general features that apply to all four player types, such as secure player-owned housing and no-conflict safe zones, are unanimously accepted among the design literati as required to attract and retain customers for the long term . After that general feature set, however, few design teams actually give much thought to applying features to player types. They have a general understanding of the features they want in the game and which features have worked or not worked in other games. They rarely dig very deeply into player needs and motivations or list them out by the Bartle types, or any other analytic measurement for that matter. Thus, the features list tends to be scattered and a bit incoherent for the design as a whole, and that usually comes back to haunt the team later on. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 230