Avoid Wasted Effort by Making Smart Pre-Proposal Decisions

|

Once you've analyzed the RFP, if there is one, or reviewed the customer's expectations if you're writing a proactive proposal, there are two important decisions you must make before you begin working on the proposal itself:

-

Is this job worth bidding on?

-

How much effort should I put into the proposal?

By making intelligent decisions before you start working on the opportunity, you can save yourself a lot of time and expense and you can feel confident that you are going after the deals that have the most potential value to you.

Perform a Bid/No Bid Analysis

Perhaps the most fundamental decision is whether to bid or not. Companies and individuals waste huge amounts of time and money creating proposals for opportunities they never had a chance of winning. In some companies, the phrase "no bid" is never uttered. These cockeyed optimists go after everything, perhaps on the theory that winning is unpredictable at best so you might as well give it a shot.

Good proposals are expensive. They're time consuming. They can soak up valuable resources. Before you start, why not get real? Do you really have a reasonable chance of winning? If you do win, can you fulfill the commitments you are making in the proposal? Can you do so profitably?

As my friend Tom Amrhein, who has written some of the largest winning proposals in U.S. government history, often counsels people, "The best way to improve your win ratio is to stop bidding for work you have no chance of winning." That's great advice, but it's often surprisingly hard for people to take.

In a "no win" situation, the competition is not truly open and fair. The company has solicited your proposal because they need a couple of dummy comparison points to show they did proper due diligence. Or they're hoping you'll quote a low price which they can then use to beat up their current vendor. Or they're operating under acquisition rules that require them to solicit a minimum number of bids, even though they already know who they want. The specifics may vary, but in all of these situations the decision maker's mind is already made up.

It's also smarter to pass on jobs you really don't want to win—or at least wouldn't want if you gave it some thought. Let's face it, not all business is business that's worth having. Some clients are so demanding, so high maintenance, so fundamentally unfair in their approach to doing business, that winning their business will make you wish you had lost.

To avoid these mistakes, implement a structured, flexible bid/no bid analysis. Develop your own bid/no bid analysis scheme, taking into account issues such as the following:

-

Are we the incumbent provider of the product or service being requested in this RFP?

-

Statistically, in government contracting incumbents win about 90 percent of all rebids. It's lower in the commercial sector, but the current incumbent vendor still has a huge advantage. Can you overcome those odds? I'm not saying you can't, but it will require a proposal that demonstrates extraordinary value to turn a decision maker away from a proven incumbent vendor.

-

-

Is the customer happy with the incumbent's performance?

-

Even in those situations where the incumbent has done a poor job and the decision maker is unhappy, the incumbent still wins almost half the time. But common sense tells you that you have a much better chance to win if the current provider has messed up.

-

-

If the customer is unhappy with the current vendor's performance, was the RFP issued to deal with those problems?

-

If the RFP was issued to solve problems inherent in the current vendor's performance, this is a good sign. You've got a chance. The client is telling you that they're really fed up. Of course, it's still possible they're just using the RFP as a stick to beat the incumbent with and aren't really committed to making a change. But it's definitely worth giving it a shot.

-

-

Do we have a strong relationship with the customer?

-

One of the Big Four consulting firms found that the single factor most predictive of a successful proposal was the existence of a strong relationship with the customer. If they had a relationship, their win ratio was over 40 percent. If there was none, the win ratio was below 10 percent.

-

-

Does this RFP play into one of our strengths?

-

Do you have provable differentiators? Can you cite compelling evidence of successful prior experience?

-

-

Does the RFP appear to be slanted toward a competitor?

-

Do the requirements strongly favor a competitor? Is there language in the RFP that comes from your competitor? It's possible your competition gave the prospective client a sample RFP, parts of which ended up in the one that was issued, but the presence of content that favors one provider should be a caution signal.

-

-

Is this project or acquisition funded?

-

Make sure there's money behind the opportunity. There are people who see nothing wrong with having you create a proposal even though they know the project isn't funded. Don't waste your time.

-

-

If not, are funds available within the client's budget?

-

Maybe the money has been allocated for the next fiscal year's budget. This will be a judgment call, but if you can get confirmation from two or more executives in the client organization, particularly if they have financial responsibility, then you have to assume the funds probably will be there.

-

-

Is the client serious about making a decision, or is this more of an exercise in information gathering?

-

Is there a compelling, imminent event in the client's universe that's driving this decision?

-

-

Will completing this project or deliverable require heavy investments of time and money on our part?

-

This doesn't mean you shouldn't bid. But it could affect the potential profitability of the deal. And winning could preclude you from pursuing other opportunities for a while.

-

-

Would winning this contract further our own goals?

-

Where do you want to move your company? What kinds of markets do you want to be in?

-

-

Is this client likely to be a strong partner or reference account in the future?

-

Landing a trophy account who is willing to be a reference or a case study may be invaluable to you downstream.

-

-

Would winning this opportunity be particularly damaging to our competitors?

-

Do you have the chance to steal away one of your competitor's most important accounts? Can you shut them out of a region or a market?

-

-

Are there strong political considerations affecting our decision to bid?

-

If you "no bid" an opportunity, will you be removed from the approved bidders list? Is the key executive at the client organization a close friend of your firm's CEO?

-

How to Say No Nicely

As the last question above suggests, when you consider whether or not to "no bid" an RFP, you must ask yourself what consequences that action may have downstream. Will a "no bid" decision limit future opportunities to bid on this customer's business? If a consultant is involved, will a "no bid" decision affect your company's relationship with that consultant in the future?

If you decide not to go forward with an opportunity, particularly one where you have already moved several steps down the sales cycle, you obviously need to tell the prospect. Simply cutting off contact or not submitting a proposal will create confusion and destroy the customer's trust. So what should you do?

The short answer is that you need to tactfully walk the line between telling them you don't want their business because of something that's wrong with them (they have lousy credit, you think their management team is nuts, and so on) and telling them that you can't do the job because there is something wrong with you (you don't have the expertise, your own management team is nuts, and so on).

So the best way to position a "no" is to suggest that the details don't provide a good business fit: "We want to make sure that the money you spend on this project produces the best possible solution for you, but in reviewing the details of the opportunity we have concluded that we are probably not the partner in this case who can provide the best solution. As a result, we respectfully decline the opportunity to bid. However, we are eager to work with you in the future where our unique combination of experience and resources can provide you with an excellent outcome."

If they press, I'd focus first on their infrastructure requirements (you want Oracle, we only do Sybase; you want brick exteriors, we only do vinyl siding). Focus next on the timing issues (given the project plan you outlined and due to other commitments, we will not have our in-house experts available to support your project when you need them). Look last at the business focus (this is an exciting opportunity, but it is not part of our core focus at this time). Those are somewhat neutral-sounding reasons.

If you can deliver the message deftly enough, you can avoid long-term commitment but still remain friends.

Determine the Appropriate Level of Effort

The second important decision you have to make, after you decide whether or not to bid in the first place, is how hard to work on the opportunity.

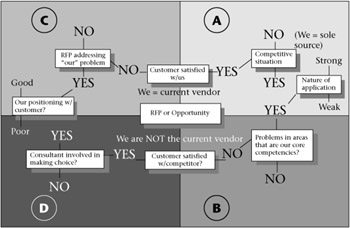

A decision tree, perhaps based on some of the questions listed above or others that you would normally use in a bid/no bid analysis, can help you determine how much effort to put into responding. For example, in Figure 8-2, the first question is "Are we the incumbent vendor?" If the answer is yes, that leads to a second question, which might be, "Is the customer satisfied with us?" If that answer is yes, we're moving into a realm where our probability of winning is high. However, if the answer to the first question is no, we are not the incumbent vendor, our chances are somewhat lower. The next question in that case might be, "Is the customer satisfied with the current vendor?" In this diagram, opportunities in the upper right quadrant (labeled A) have a high probability of being successful. Opportunities in quadrant D (lower left) are almost guaranteed losers. The other two quadrants have probabilities somewhere in between, with a slightly stronger likelihood going to those opportunities where you are the incumbent (quadrant C).

Figure 8-2: Determining the Level of Effort.

If you can create this kind of decision tree, you will be able to determine how much effort to put into an opportunity. At the top level, your very best opportunities call for dedicated commitment and focused effort. You will create a formal proposal that is highly customized to the client and the opportunity.

The next level down is an opportunity where you believe the competitive playing field is open and fair, but your likelihood of winning is substantially lower. For such an opportunity, you would be wise to spend less time and effort, but still try to deliver a customized proposal. The difference is that you will rely heavily on boilerplate and spend less time during the editing process on customizing the content.

At the next level, we may be in a zone where there are lots of caution signs. We are perilously close to a "no bid," but if you decide to respond, you should consider submitting a generic proposal or one that you have generated from a proposal automation system, but not spent much time revising. Your focus should be on turning the proposal around extremely fast, in no more than a few hours, and the effort should involve the absolute minimum number of contributors.

At the lowest level, of course, we have the option of not bidding at all. In that case, we simply prepare a tactful letter explaining that this opportunity does not seem right for us.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 130