Section 10.4. Content

10.4. ContentWe define content broadly as "the stuff in your web site." This may include documents, data, applications, e-services, images, audio and video files, personal web pages, archived email messages, and more. And we include future stuff as well as present stuff. Users need to be able to find content before they can use itfindability precedes usability. And if you want to create findable objects, you must spend some time studying those objects. You'll need to identify what distinguishes one object from another, and how document structure and metadata influence findability. You'll want to balance this bottom-up research with a top-down look at the site's existing information architecture. 10.4.1. Heuristic EvaluationMany projects involve redesigning existing web sites rather than creating new ones. In such cases, you're granted the opportunity to stand on the shoulders of those who came before you. Unfortunately, this opportunity is often missed because of people's propensity to focus on faults and their desire to start with a clean slate. We regularly hear our clients trashing their own web sites, explaining that the current site is a disaster and we shouldn't waste our time looking at it. This is a classic case of throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Whenever possible, try to learn from the existing site and identify what's worth keeping. One way to jump-start this process is to conduct a heuristic evaluation. A heuristic evaluation is an expert critique that tests a web site against a formal or informal set of design guidelines. It's usually best to have someone outside the organization perform this critique, so this person is able to look with fresh eyes and be largely unburdened with political considerations. Ideally, the heuristic evaluation should occur before a review of background materials to avoid bias. At its simplest, a heuristic evaluation involves one expert reviewing a web site and identifying major problems and opportunities for improvement. This expert brings to the table an unwritten set of assumptions about what does and doesn't work, drawing upon experiences with many projects in many organizations. This practice is similar to the physician's model of diagnosis and prescription. If your child has a sore throat, the doctor will rarely consult a reference book or perform extensive medical tests. Based on the patient's complaints, the visible symptoms, and the doctor's knowledge of common ailments, the doctor will make an educated guess as to the problem and its solution. These guesses are not always right, but this single-expert model of heuristic evaluation often provides a good balance between cost and quality. At the more rigorous and expensive end of the spectrum, a heuristic evaluation can be a multi-expert review that tests a web site against a written list[*] of principles and guidelines. This list may include such common-sense guidelines as:

Each expert reviews the site independently and makes notes on how it fares with respect to each of these criteria. The experts then compare notes, discuss differences, and work toward a consensus. This reduces the likelihood that personal opinion will play too strong a role, and creates the opportunity to draw experts from different disciplines. For example, you might include an information architect, a usability engineer, and an interaction designer. Each will see very different problems and opportunities. This approach obviously costs more, so depending on the scope of your project, you'll need to strike a balance in terms of number of experts and formality of the evaluation. 10.4.2. Content AnalysisContent analysis is a defining component of the bottom-up approach to information architecture, involving careful review of the documents and objects that actually exist. What's in the site may not match the visions articulated by the strategy team and the opinion leaders. You'll need to identify and address these gaps between top-down vision and bottom-up reality. Content analysis can take the shape of an informal survey or a detailed audit. Early in the research phase, a high-level content survey is a useful tool for learning about the scope and nature of content. Later in the process, a page-by-page content audit or inventory can produce a roadmap for migration to a content management system (CMS), or at least facilitate an organized approach to page-level authoring and design. 10.4.2.1. Gathering contentTo begin, you'll need to find, print, and analyze a representative sample of the site's content. We suggest avoiding an overly scientific approach to sample definition. There's no formula or software package that will guarantee success. Instead, you need to use some intuition and judgment, balancing the size of your sample against the time constraints of the project. We recommend the Noah's Ark approach. Try to capture a couple of each type of animal. Our animals are things like white papers, annual reports, and online reimbursement forms, but the difficult part is determining what constitutes a unique species. The following dimensions should help distinguish one beast from another and build toward a diverse and useful content sample:

Consider what other dimensions might be useful for building a representative content sample for your particular site. Possibilities include intended audience, document length, dynamism, language, and so on. As you're balancing sample size against time and budget, consider the relative number of members of each species. For example, if the site contains hundreds of technical reports, you certainly want a couple of examples. But if you find a single white paper, it's probably not worth including in your sample. On the other hand, you do need to factor in the importance of certain content types. There may not be many annual reports on your web site, but they can be content-rich and very important to investors. As always, your judgment is required. A final factor to consider is the law of diminishing returns. While you're conducting content analysis, you'll often reach a point where you feel you're just not learning anything new. This may be a good signal to go with the sample you've got, or at least take a break. Content analysis is only useful insofar as it teaches you about the stuff in the site and provides insights about how to get users to that stuff. Don't just go through the motions. It's unproductive and incredibly boring. 10.4.2.2. Analyzing contentWhat are you looking for during content analysis? What can you hope to learn? One of the side benefits of content analysis is familiarity with the subject matter. This is particularly important for consultants who need to quickly become fluent in the language of their client. But the central purpose of content analysis is to provide data that's critical to the development of a solid information architecture. It helps you reveal patterns and relationships within content and metadata that can be used to better structure, organize, and provide access to that content. That said, content analysis is quite unscientific. Our approach is to start with a short list of things to look for, and then allow the content to shape the process as you move forward. For example, for each content object, you might begin by noting the following:

This short list will get you started. In some cases, the object will already have metadata. Grab that, too. However, it's important not to lock into a predefined set of metadata fields. You want to allow the content to speak to you, suggesting new fields you might not have considered. You'll find it helpful to keep asking yourself these questions:

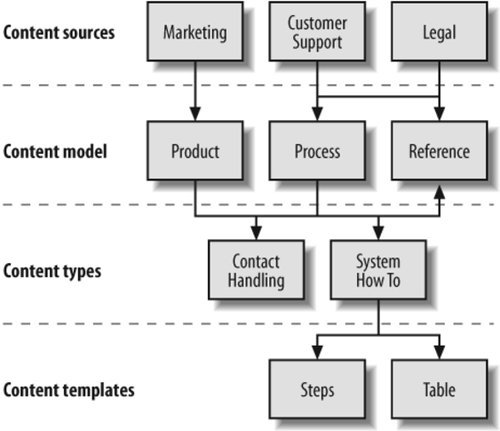

Moving beyond individual items, also look for patterns and relationships that emerge as you study many content objects. Are certain groupings of content becoming apparent? Are you seeing clear hierarchical relationships? Are you recognizing the potential for associative relationships, perhaps finding disparate items that are linked by a common business process? Because of the need to recognize patterns within the context of the full sample, content analysis is by necessity an iterative process. It may be on the second or third pass over a particular document that the light bulb blinks on and you discover a truly innovative and useful solution. With the exception of true bottom-up geeks (and we use the term respectfully), most of us don't find content analysis especially thrilling or addictive. However, experience has proven that this careful, painstaking work can suggest new insights and produce winning information architecture strategies. In particular, content analysis will help you in the design phase, when you begin fleshing out document types and metadata schema. But it also provides valuable input into the broader design of organization, labeling, navigation, and searching systems. 10.4.3. Content MappingHeuristic evaluation provides a top-down understanding of a site's organization and navigation structures, while content analysis provides a bottom-up understanding of its content objects. Now it's time to bridge these two perspectives by developing one or more content maps. A content map is a visual representation of the existing information environment (see Figure 10-4). Content maps are typically high-level and conceptual in nature. They are a tool for understanding, rather than a concrete design deliverable. Figure 10-4. A small slice of a content map Content maps vary widely. Some focus on content ownership and the publishing process. Some are used to visualize relationships between content categories. And others explore navigation pathways within content areas. The goal of creating a content map is to help you and your colleagues wrap your minds around the structure, organization, and location of existing content, and ultimately to spark ideas about how to provide improved access. 10.4.4. BenchmarkingWe use the term benchmark informally to indicate a point of reference from which to make comparative measurements or judgments. In this context, benchmarking involves the systematic identification, evaluation, and comparison of information architecture features of web sites and intranets. These comparisons can be quantitative or qualitative. We might evaluate the number of seconds it takes a user to perform a task using competing web sites, or take notes about the most interesting features of each site. Comparisons can be made between different web sites (competitive benchmarking) or between different versions of the same web site (before-and-after benchmarking). In both cases, we've found benchmarking to be a flexible and valuable tool. 10.4.4.1. Competitive benchmarkingBorrowing good ideas, whether they come from competitors, friends, enemies, or strangers, comes naturally to all of us. It's part of our competitive advantage as human beings. If we were all left to our own devices to invent the wheel, most of us would still be walking to work. However, when we take these copycat shortcuts, we run the risk of borrowing bad ideas as well as good ones. This happens all the time in the web environment. Since the pioneering days of web site design, people have repeatedly mistaken large financial outlays and strong marketing campaigns as signs of good information architecture. Careful benchmarking can catch this misdirected copycatting before it gets out of control. For example, when we worked with a major financial services firm, we ran up against the notion that Fidelity Investments' long-standing position as a leader within the industry automatically conferred the gold standard upon its web site. In several cases, we proposed significant improvements to our client's site but were blocked by the argument, "That's not how Fidelity does it." To be sure, Fidelity is a major force in the financial services industry, with a broad array of services and world-class marketing. However, in 1998, the information architecture of its web site was a mess. This was not a model worth following. To our client's credit, they commissioned a formal benchmarking study, during which we evaluated and compared the features of several competing sites. During this study, Fidelity's failings became obvious, and we were able to move forward without that particular set of false assumptions. The point here is that borrowing information architecture features from competitors is valuable, but it must be done carefully. 10.4.4.2. Before-and-after benchmarkingBenchmarking can also be applied to a single site over time to measure improvements. We can use it to answer such return-on-investment (ROI) questions as:

Before-and-after benchmarking forces you to take the high-level goals expressed in your statement of mission and vision, and tie them to specific, measurable criteria. This forced clarification and detail-orientation will drive you toward a better information architecture design on the present project, in addition to providing a point of reference for evaluating success. Following are the advantages of before-and-after benchmarking, as well as those of competitive benchmarking: Benefits of before-and-after benchmarking

Benefits of competitive benchmarking

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 194