Business networks in China and overseas Chinese communities

One can often hear the word guanxi in any Chinese community, whether it is mainland China (Bian 1994; Wu 1995a), Hong Kong (Wong 1991), Singapore (Wong 1995) or Taiwan (Kao 1991; Numazaki 1985), though there may be some slight differences in pronunciation as a result of the distinctive Chinese dialects spoken in those communities.

Guanxi has been regarded as a special relationship two persons have with each other (Alston 1989), as a special kind of personal relationship in which long-term mutual benefit is more important than short- term individual gain (Zamet and Bovarnick 1986), and as having the status and intensity of an on-going relationship between two parties (Kirkbride et al 1991). Bian (1994) states that guanxi has two meanings attached to it: the indirect relationship between two people and the direct relationship between two people and a contact person. For the purpose of this study, guanxi can be defined as a special personal relationship in which long-term mutual benefit is more important than short-term individual gain and contains the key elements of indirect relationship between two people through proper introduction by a third party, and direct relationship between two people who trust each other and the contact person.

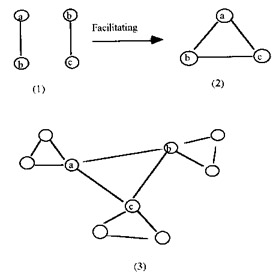

While guanxi operates on a dyadic level, guanxiwang (network) [*] certainly goes further than that. Guanxiwang refers to a network of exchanges or transactions between two parties and beyond. Goods and services such as physical products or favours exchanged can be anything of value and mutual benefit to the parties concerned , for example, raw materials, promotion, gifts, information, facilitation and so on. Guanxiwang obtains when one set of separate, personal and total relationships between two individuals, A and B, and another set of such relationships between B and C are interlinked through the common agent, B, acting as a witness and facilitator (see Figure 4.3.1). As a result, the originally 'total and personal relationship' (Alston 1989) transforms into a complex network of social exchanges with such inter- linkage extended into other sets through numerous common agents like A, B and C. Therefore, it can be concluded that guanxi is not simply, as many believe, one of the key features of Chinese culture (Lockett 1988) or one of the key 'themes' which depict core aspects of Chinese values (Kirkbride et al 1991); it is the mother of all relationships.

Figure 4.3.1: Guanxi and guanxiwang

Although there are various kinds of guanxiwang in China and overseas Chinese communities, they can be divided into two main groups: social networks and business networks. It is important to understand the relationship between a social network and a business network. A social network can be broadly defined as a web of social relationships established within the sphere of core family members, extended family members, friends , classmates, fellow townsmen and so on. According to Redding (1990), the Chinese social network consists of lineage, village or neighbourhood, clan or collection of lineage and special interest associations. Their main function is to protect and help each other and to have an ethnic and/or unique identity in a wider social context. A business network can be defined as a web of business organisations to create or internalise a market for the purpose of profit maximisation or cost minimisation for all the members concerned.

There are four distinct types of such inter-firm networks:

-

ownership networks (firms linked though common ownership);

-

investment networks (firms linked by capital and investment;

-

production networks (firms linked by production sequences); and

-

distribution networks (firms linked by the distribution of commodities) (Hamilton et al 1990).

While a social network is not a business network per se, the former can reinforce and overlap with the latter (Omohundro 1983). It has been widely accepted that one needs a good personal relationship ( guanxi ) to do business successfully in the Chinese communities such as China, Taiwan and Singapore (Redding 1990). It is common practice for Chinese to do business with trusted friends. Johanson and Mattsson (1987) stress that it is individual actors that are the major players in an industrial or business network. Deglopper (1978: 297) says: 'Business relations are always, to some degree, personal relations.' Consequently, sometimes the difference between the two can become very blurred. There is an increasing body of research devoted to the study of the relationship between social/personal networks and business networks (Kao 1991; Numazaki 1985; Omohundro 1983).

There is a bias in the study of Chinese business networks. Although there exists much corruption among overseas Chinese (Redding 1990), very little has been mentioned in the study of overseas Chinese business networks. Yoshihara (1991) may be one of the few exceptions to echo indigenous peoples' view that Chinese businessmen in south-east Asia are not genuine entrepreneurs because they are basically successful by making the right political connections, favours and contracts. However, when it concerns mainland China, guanxiwang is immediately branded as corruption (Li and Wu 1993; Agelasto 1996; The Economist 1989:62). Many people often treat guanxi and guanxiwang as derogatory terms. Guanxiwang is regarded as an unhealthy social tendency. The truth is guanxiwang per se is purely a form of organisational governance. Nothing more, nothing less. It has nothing to do with corruption when a transaction is legal and does not infringe any public interests, but simply takes place between members within a business network. Guanxiwang only becomes corrupt when exchange or transaction taking place within a guanxiwang involves corrupt activities such as bribery. Because of the special characteristics of guanxiwang such as trust and bonding, corrupt deals are more likely to take place between members of a guanxi- wang particularly when an adequate and effective legal and disciplinary system is lacking.

Networks are essential to overseas Chinese success in China. They allow access to the right officials at the township or village level. Benefits flow both ways through the networks (East Asia Analytical Unit 1995). Business networks existed throughout the history of the People's Republic of China (Bian 1994). During the period of the Cultural Revolution, the classic market was not allowed to exist. For example, there were campaigns to cut 'the tail of capitalism ' in the countryside. With the failure of bureaucratic governance and nonexistence of market, an alternative, the network, played a major role in social and industrial exchanges and transactions in China. In a recent empirical research on the relationship between guanxi and the allocation of urban jobs in China, Bian (1994) found that guanxi accounted for a considerable proportion of jobs in all historical periods between 1949 and 1988. The operation of network was suppressed by a tight and rigid bureaucratic control before the economic reform. It has been revealed that with the loosening of state control, guanxi had been widely used to substitute for the imperfect market (Bian 1994). Solinger (1989) discovered that the withdrawal of the planning system based on quotas and local government-directed input and output transactions gave rise to relational contracting in which many of the former business relationships were maintained .

Therefore, it can be concluded that with the shared legacies of social history and the key Chinese cultural values, there is no significant difference between business networks in China and their counterparts in overseas Chinese communities. The difference, if any, is diminishing rapidly with the ever increasing number of cross-border investments by overseas Chinese in China and the further deepening of Chinese economic reform.

[*] Network and guanxiwang are interchangeable throughout this chapter.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 648

- Chapter I e-Search: A Conceptual Framework of Online Consumer Behavior

- Chapter III Two Models of Online Patronage: Why Do Consumers Shop on the Internet?

- Chapter IV How Consumers Think About Interactive Aspects of Web Advertising

- Chapter V Consumer Complaint Behavior in the Online Environment

- Chapter XV Customer Trust in Online Commerce