Delighted Customers

| In 1984, Dr. Noriaki Kano of Tokyo Rika University published a landmark paper on "attractive quality."[10] In it, he presented the Kano model, a tool to help clarify how to create great products that delight customers (see Figure 3.1).

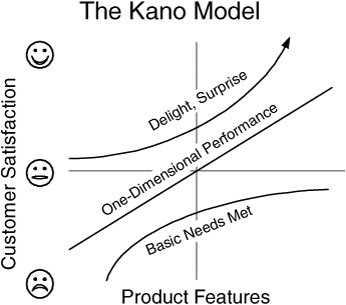

Figure 3.1. The Kano model The Kano model shows that just to get in the door, you have to meet customers' basic needs. After that, there are two areas for differentiation: 1) increase performance by adding features, or 2) discover needs that customers aren't even aware of and delight them by meeting these needs. Kano noted that increasing performance gives linear resultscustomer satisfaction is increased in direct proportion to the increased performance. To get an exponential increase in satisfaction, you need to discover and meet unmet needs and thus surprise and delight customers. Kano said that great products do not come from simply listening to what customers ask for, but from developing a deep understanding of the customer's world, discovering unmet needs, and surprising customers by catering to these needs. This is the way to create delighted customers. Google seems to be very good at delighting customers. As we travel around the world giving talks and classes, we usually ask the question: How many people in the room really like Google? Invariably, just about everyone raises their hand, and then we hear about an amazing number of ways in which people use Google products. Our son regularly sends us pointers to unique new Google features. Our granddaughter routinely uses Google to do elementary school research. Deep Customer Understanding"Great software grows out of a mind-meld between a person who really understands the business and a person who really understands the technology," Tom was telling an interviewer. Suddenly the reporter's eyes lit up. "I understand!" he exclaimed, and then he interrupted the interview to tell us this story:

There's plenty of average software in the world, but occasionally some truly innovative software catches our attention. And we want to know "How do they do that?" or more accurately, "How can we do that?" Focus on the JobIn 1982, 30-year-old Scott Cook was wondering the same thing.[11] The IBM PC had just been introduced, and Cook was one of a host of entrepreneurs trying to invent software products to sell to PC owners. Cook had an advantage over his peers. He had spent five years in brand management at Procter & Gamble, where he acquired a playbook for creating and selling products that would change people's lives. So he did what any good P&G brand manager would do. He started by finding a job that needed to be done for which no optimal tool yet existed. He noticed his wife's frustration with managing the family finances and decided that financial management software could provide a better tool to get that job done. Cook wasn't alone in this discovery. By the time he had founded Intuit and introduced Quicken in 1983, it had no fewer than 46 competitors.

At P&G Cook had learned to deal with competition by thoroughly understanding the job that people need to do, what was wrong with current tools, and exactly what it meant to do the job better. He started by methodically researching how people currently managed their finances. He learned that most people did only three things: pay bills, maintain their check register, and periodically total and review their expenditures. And he discovered that they found these jobs unpleasant and wanted to complete them as fast as possible. So Quicken was designed from the beginning to do threeand only threejobs faster than they could be done manually. By shifting his view of the competition to paper and pencil, Cook could not only ignore existing software competitors, he changed the basis of competition. The P&G playbook included research throughout the product lifecycle. Cook found that competing financial software was laden with features and took hours to install. Cook decided to create a program so simple that a PC novice could install it and be writing checks in fifteen minutes. Then he more or less invented usability testing so that Quicken 1.0 could be tested and simplified until it met this goal. Meanwhile, the same tests confirmed that it took experienced PC users up to five hours to write their first check on the feature-laden competing products. Because having a better tool is not enough, Intuit's research extended to packaging and pricing. The people who have a job to do must clearly understand that there is a better tool for the job. Finally, Intuit continued to improve the tool, making sure that it maintained its position as the best tool for the job. Cook contends that value is created by focusing on the job that needs to be done and improving the product so that it does the job better than any alternative.[12]

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 89