The Research Approach

|

Any job can be considered from two perspectives: tasks and personal competencies. Tasks are a break out of the job itself and are usually defined in terms of the minimum requirements for acceptable performance. By contrast, personal competencies describe what the person brings to the job that allows him to do the job in an outstanding way. These competencies may include motives, traits, aptitudes, knowledge, or skills. For any given job defined as a set of tasks, personal competencies are what superior performers have or do which allow them to achieve superior results.

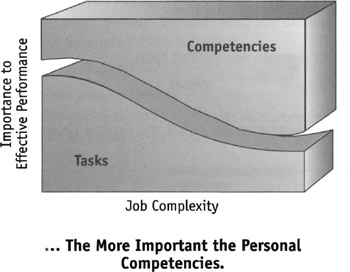

A systematic approach to job analysis should consider both tasks and personal competencies, as shown in Figure 2. The inclusion of personal competencies pushes beyond the minimum job requirements to what makes for superior performance. DSMC chose to study personal competencies of project managers rather than use traditional methods like task analysis and expert panels that had been employed in the past. The reasoning is that for more complex jobs, such as project managers in defense acquisition, it is more important to study what each project manager brings to the job that results in outstanding performance. Figures 2, 3, and 4 and Tables 2 and 3 are provided courtesy of Cambria Consulting in Boston, MA who were employed as a support contractor for the initial DSMC research studies (Klemp 1982).

Figure 2: The More Complex the Job …

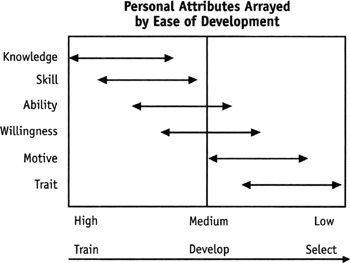

Figure 3: Personal Attributes Arrayed by Ease of Development

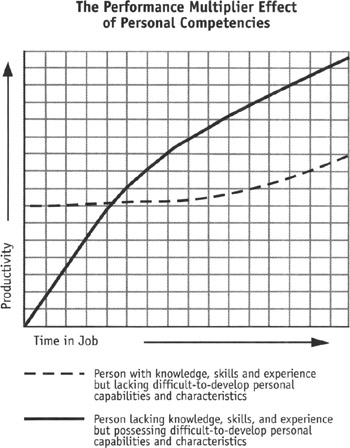

Figure 4: The Performance Multiplier Effect of Personal Competencies

| New Product Development Managers |

| What the experts thought: |

| √ Senses trends and identifies opportunities |

| √ Takes risks |

| √ Is creative—able to generate new product ideas |

| √ Has knowledge of manufacturing processes |

| New Product Development Managers |

| What the competency research found: |

| √ Senses trends and identifies opportunities |

| |

| |

| |

| In addition, the research revealed: |

| √ Has skill in informal influence |

| √ Has skill in facilitating groups |

As an example, consider the difference between a capable pilot and a fighter ace. The basic skills of flying can be considered of moderate complexity on the Figure 2 diagram and are probably amenable to a task-analysis approach. On the other hand, a fighter ace or "top-gun" pilot would be difficult to characterize based on tasks alone. This is especially true if you were interested in what differentiates the ace from the other capable pilots in the squadron. This is where the analysis of personal competencies is of most value. One could argue that a project manager's job is on the right side of the complexity scale in Figure 2 along with the fighter ace and, therefore, is also most suitable for analysis of personal competencies.

Using critical incident interviews and detailed follow-up surveys, the selected research process gets beneath espoused theories about what it takes to do a job, to what the best performers actually do. Past studies (Klemp 1982) have shown that job experts are often wrong in their assumptions about what it takes to do a job well. This is illustrated in Tables 2 and 3, which summarize a private sector research study on new product development managers in different divisions of the General Electric Company. At the start of the research project, a panel of company new product development experts was assembled and asked to predict the competencies that would characterize top performers (Table 2). Then, selected top performers from the different divisions (based on results achieved) were interviewed and surveyed. The research findings confirmed only one of the expert panel competencies but found additional competencies the experts had not identified (Table 3).

Even the top performers themselves are often unaware ("unconsciously competent") of what they do that makes them so effective. An interesting example from Training Magazine (Gilbert 1988) illustrates this point. Two researchers interviewed the famous American College football Coach Paul "Bear" Bryant at the University of Alabama and asked what he did that made him such a great coach. Coach Bryant stressed recruitment, motivation, and teamwork in his interview. However, instead of immediately writing up the findings from their interview notes, the researchers stayed on for several days and actually observed Coach Bryant in practice sessions and during games. What they found was that Coach Bryant didn't actually do most of the things he alluded to in the interviews. They also discovered other "new" behaviors, such as detailed observation of player performance and immediate feedback, that actually accounted for Coach Bryant's success. As the article states, "exemplary performers differ very little from average ones, but that the differences are enormously valuable" (Gilbert 1988).

The competency research process is outlined in Table 4 and has several benefits. It identifies the characteristics that distinguish outstanding project managers from their contemporaries. The research focuses on the critical few characteristics that make the most difference in job performance. These characteristics are defined in terms of observable job-related behavior rather than abstract concepts. Finally, the resulting leadership model serves as an excellent communication tool and training model to move organizations toward their goal of creating a cadre of top performing project leaders.

| Interviews

|

| Surveys

|

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 207