Defining Project Management

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Project management is the supervision and control of the work required to complete the project vision. The project team carries out the work needed to complete the project, while the project manager schedules, monitors, and controls the various project tasks. Projects, being the temporary and unique things that they are, require the project manager to be actively involved with the project implementation. They are not self-propelled.

Project management is comprised of the following nine knowledge areas. Chapters 4 through 12 will explore the knowledge areas in detail.

-

Project Integration Management This knowledge area focuses on project plan develop and execution.

-

Project Scope Management This knowledge area deals with the planning, creation, protection, and fulfillment of the project scope.

-

Project Time Management Time management is crucial to project success. This knowledge area covers activities, their characteristics, and how they fit into the project schedule.

-

Project Cost Management Cost is always a constraint in project management. This knowledge area is concerned with the planning, estimating, budgeting, and control of costs.

-

Project Quality Management This knowledge area centers on quality planning, assurance, and control.

-

Project Human Resource Management This knowledge area focuses on organizational planning, staff acquisition, and team development.

-

Project Communications Management The majority of a project manager's time is spent communicating. This knowledge area details how communications can improve.

-

Project Risk Management Every project has risks. This knowledge area focuses on risk planning, analysis, monitoring, and control.

-

Project Procurement Management This knowledge area involves planning, solicitation, contract administration, and contract closeout.

Defining the Project Life Cycle

One common attribute of all projects is that they eventually end. Think back to one of your favorite projects. The project started with a desire to change something within an organization. The idea to change this 'something' was mulled around, kicked around, and researched until someone with power deemed it a good idea to move forward and implement the project. As the project progressed towards completion there were some very visible phases within the project life. Each phase within the life of the project created a deliverable.

For example, consider a project to build a new warehouse. The construction company has some pretty clear phases within this project: research, blueprints, approvals and permits, breaking ground, laying the foundation, and so on. Each phase, big or small, results in some accomplishment that everyone can look to and say, 'Hey! We're making progress!' Eventually the project is completed and the warehouse is put into production.

At the beginning of the project, through planning, research, experience, and expert judgment, the project manager and the project team will plot out when each phase should begin, when it should end, and the related deliverable that will come from each phase. Often, the deliverable of each phase is called a milestone. The milestone is a significant point in the schedule that allows the stakeholders to see how far the project has progressed-and how far the project has to go to reach completion.

Defining the Project Management Process

Will all projects have the same phases? Of course not! A project to create and manufacture a new pharmaceutical will not have the same phases as a project to build a skyscraper. Both projects, however, can map to the five project management processes. These processes are typical of projects, and are iterative in nature-that is, you don't finish a process never to return. Let's take a look at each process and its attributes.

Initiating

This process launches the project, or phase. The needs of the organization are identified and alternative solutions are researched. The power to launch the project or phase is given through a project charter, and when initiating the project, the wonderful project manager is selected.

Planning

Can you guess what this process is all about? The planning process requires the project manager and the project team to develop the various core and subsidiary management plans necessary for project completion. This process is one of the most important pieces of project management.

Executing

This process allows the project team and vendors to move toward completing the work outlined in the Planning process. The project team moves forward with completing the project work.

Controlling

The project manager must control the work the project team and the vendors are completing. The project manager checks that the deliverables of the phases are in alignment with the project scope, defends the scope from changes, and confirms the expected level of quality of the work being performed. This process also requires the project manager to confirm that the cost and schedule are in sync with what was planned. Finally, the project team will inform the project manager of their progress, who will, in turn, report on the project's progress to the project sponsor, to management, and perhaps even to key stakeholders in the organization.

Closing

Ah, the best process of them all. The closing process, sometimes called the project postmortem, involves closing out the project accounts, completing final acceptance of the project deliverables, filing the necessary paperwork, and assigning the project team to new projects. Oh yeah, and celebrating!

Most projects have similar characteristics, such as the following:

They Are Demanding

The stakeholders, the people with a vested interested in the project, are all going to have different expectations, needs, and requests of the project deliverables. No doubt there will be conflict between the stakeholders.

They Have Clear Requirements

Projects should have a clearly defined set of requirements. These requirements will set the bar for the actual product or service created by the project, the quality of the project, and the timeliness of the project's completion.

They Come with Assumptions

Projects also have assumptions. Assumptions are beliefs held to be true, but that haven't been proven. For example, the project may be operating under the assumption that the project team will have access to do the work at any time during the workday, rather than only in the evenings or weekends.

Constraints Are Imposed

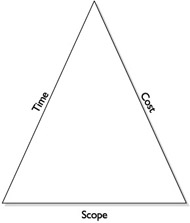

Within every project there is a driving force for the project. You've probably experienced some force first-hand. For example, ever had a project that had to be done by an exact date or you'd face fines and fees? This is a schedule constraint. Or a project that could not go over it's set budget? This is a financial constraint. Or what about a project that had to hit an exact level of quality regardless of how long the project took? This is scope constraint. All are forces that tend to be in competition with each other.

Specifically, there are three constraints that a project manager will encounter:

-

Project Scope The scope of the project constitutes the parameters of what the project will, and will not, include. As the project progresses, the stakeholders may try to change the project scope to include more requirements than what was originally planned for (commonly called scope creep). Of course, if you change the project scope to include more deliverables, the project will likely need more time and/or money to be completed. We will talk about scope in Chapter 5.

-

Schedule This is the expected time when the project will be completed. Realistic schedules don't come easily. You'll learn all about scheduling and estimating time in Chapter 6. As you may have experienced, some projects require a definite end date rather than, or in addition to, a definite budget. For example, imagine a manufacturer creating a new product for a tradeshow. The tradeshow is not going to change the start date of the show just because the manufacturer is running late with their production schedule.

-

Cost Budgets, monies, greenbacks, dead presidents, whatever you want to call it-the cost of completing the project is always high on everyone's list of questions. The project manager must find a method to accurately predict the cost of completing the project within a given timeline, and then control the project to stay within the given budget. We will learn more about this in Chapter 7. Sounds easy, right? The following diagram illustrates the Iron Triangle of scope, schedule, and cost constraints.

Consider the Project Risk

Do you play golf? In golf, as in project management, there is a theory called The Risk-Reward Principle. You're teeing off for the seventh hole. If you shoot straight, you can lay up in the fairway, shoot again, and then two-putt for par. Pretty safe and predictable. However, if you have confidence in your driver, you may choose to cut the waterway and get on the green in one. If you accept and beat that risk, you'll have a nice reward. Choke and land in the water and you're behind the game. In project management, the idea is the same. Some risks are worth taking, while others are worth the extra cost to avoid. You'll learn all about risks in Chapter 11.

Consider the Expected Quality

What good is a project if it is finished on time and on budget, but the quality of the deliverable is so poor it is unusable? Some projects have a set level of quality that allows the project team to aim for. Other projects follow the organization's Quality Assurance Program such as ISO 9000. And, unfortunately, some projects have a general, vague idea of what an acceptable level of quality is. Without a specific target for quality, trouble can ensue. The project manager and project team may spend more time and monies to hit an extremely high level of quality when a lower, expected level of quality would suffice for the project. Quality is needed, but an exact target of expected quality is demanded.

Exam Watch

Project constraints influence practically all areas of the project process. Consider constraints as a ruling requirement over the project. Common constraints you'll encounter are time constraints in the form of deadlines and the availability of resources.

Management by Projects

In today's competitive, tight-margin business world, organizations have to move and respond quickly to opportunity. Many companies have moved from a functional environment-that is, organization by function-to an organization, or management, by projects. A company that organizes itself by job activity, such as sales, accounting, information technology, and other departmental entities is a functional environment. A company that manages itself by projects may be called a projectized company.

An organization that uses projects to move the company forward is using the Management by Projects approach. These project-centric entities could manage any level of their work as a project. These organizations, however, apply general business skills to each project to determine their value, efficiency, and, ultimately, their return on investment. As you can imagine, some projects are more valuable, more efficient, or more profitable than others.

There are many examples of organizations that use this approach. Consider any business that completes projects for their clients, such as architectural, graphic design, consulting, or other service industries. These service-oriented businesses typically complete projects as their business.

Here are some other examples of management by projects:

-

Training employees for a new application or business method

-

Marketing campaigns

-

The entire sales cycle from product or service introduction, proposal, and sales close

-

Work completed for a client outside of the organization

-

Work completed internally for an organization

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 209