Section 9.3. Modeling Cybersecurity

9.3. Modeling CybersecurityCybersecurity economics is a nascent field, bringing together elements of cybersecurity and economics to help decision-makers understand how people and organizations invest constrained resources in protecting their computer systems, networks, and data. Among the many questions to ask about cybersecurity investments are these:

Transferring ModelsWhat kinds of models are available to help us make good investment decisions by answering questions such as these? Typical first steps often involve applying a standard approach in one discipline to a problem in a second discipline. For example, to answer the first question, Gordon and Loeb [GOR02a] apply simple accounting techniques to develop a model of information protection. They consider three parameters: the loss conditioned on a breach's occurring, the probability of a threat's occurring, and the vulnerability (defined as the probability that a threat, once realized, would be successful). The impact is expressed in terms of money expected to be lost by the organization when the breach occurs. They show that, for a given potential loss, the optimal amount an organization should spend to protect an information asset does not always increase as the asset's vulnerability increases. Indeed, protecting highly vulnerable resources may be inordinately expensive. According to Gordon and Loeb's models, an organization's best strategy may be to concentrate on information assets with midrange vulnerabilities. Moreover, they show that, under certain conditions, the amount an organization should spend is no more than 36.8 percent of the expected loss. However, Willemson [WIL06] constructs an example where a required investment of 50 percent may be necessary; he also shows that, if the constraints are relaxed slightly, up to 100 percent is required. Campbell et al. [CAM03] address the second question by examining the economic effect of information security breaches reported in newspapers or publicly traded U.S. corporations. Common wisdom is that security breaches have devastating effects on stock prices. However, Campbell and her colleagues found only limited evidence of such a reaction. They show that the nature of the breach affects the result. There is a highly significant negative market reaction for information security breaches involving unauthorized access to confidential data, but there seems to be no significant reaction when the breach involves no confidential information. Models based on these results incorporate the "snowball effect, accruing from the resultant loss of market share and stock market value" [GAL05]. Gal-Or and Ghose [GAL05] use the Campbell result in addressing the third problem. Using game theory, they describe the situation as a non-cooperative game in which two organizations, A and B, with competing products choose optimal levels of security investment and information sharing. A and B choose prices simultaneously. The game then helps them decide how much information to share about security breaches. Included in the game are models of cost and demand that reflect both price and competition. Their model tells us the following about the costs and benefits of sharing information about security breaches:

In general, there are strong incentives to share breach information, and the incentives become stronger as the firm size, industry size, and amount of competition grow. Models such as these offer an initial framing of the problem, particularly when researchers are exploring relationships and setting hypotheses to obtain a deeper understanding. However, as with any new (and especially cross-disciplinary) research area, initial understanding soon requires a broader reach. Models for Decision-MakingThe reach of initial models is being broadened in many ways. For example, some researchers are looking to anthropology, sociology, and psychology to see how human aspects of decision-making can be woven into economic models. This research hopes to expand the explanatory power of the models, enabling them to reflect the complexities of human thought about problems that are sometimes difficult to comprehend but that have a clear bearing on making economic decisions about cybersecurity investments. For example, as we saw with the Gordon and Loeb model, many economic models include parameters to capture the risk that various problems will occur. But deriving a reasonable probability for the risk is not always the only problem with risk quantification. Once the risk factors are calculated, they must be communicated in a way that allows a decision-maker to compare and contrast scenarios. Jasanoff [JAS91] describes the difficulty of understanding and contrasting numbers that do not relate easily to everyday experience. Framing the IssueWhen presented with information about risk in terms of probability and payoff, researchers have found that

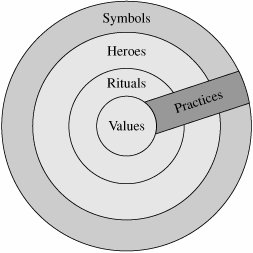

Many cybersecurity risks have a very small likelihood of occurrence but can have an enormous impact in terms of cost, schedule, inconvenience, or even human life. More generally, the way a problem is framed can make a big difference in the choices people make. For example, when cybersecurity investment choices are portrayed as risk avoidance or loss avoidance, the options are immersed in one kind of meaning. However, when the choices are described as opportunities to establish a competitive edge as a totally trustworthy company or as required by the demands of recognized "best practices" in the field or industry, the same group may make very different investment selections. Swanson and Ramiller [SWA04] suggest that this phenomenon is responsible for technology adoption that seems otherwise irrational. Thus, the communication of information can lead to a variety of framing biases. Decision-support systems based on models of cybersecurity economics can use this kind of behavioral science information about framing and risk perception to communicate risk so that the decision maker selects the best options. Group BehaviorWhen behavioral scientists examine economic actions, they question whether rational choice alone (assumed in most cybersecurity economics models) can adequately model how economic agents behave. Behavioral economics is based on hypotheses about human psychology posed by researchers such as Simon [SIM78], Kahneman and Tversky [KAH00], and Slovic et al. [SLO02]. These researchers have shown not only that people make irrational choices but also that framing the same problem in different but equivalent ways leads people to make significantly different choices. One of the key results has been a better understanding of how humans use heuristics to solve problems and make decisions. Often, decision-makers do not act alone. They act as members of teams, organizations, or business sectors, and a substantial body of work describes the significant differences in decisions made by individuals acting alone and acting collectively. When an individual feels as if he or she is part of a team, decisions are made to meet collective objectives rather than individual ones (Bacharach [BAC99] and Sugden [SUG00]). This group identity leads to team reasoning. But the group identity depends on a sense of solidaritythat is, on each team member's knowing that others are thinking the same way. Normative expectations derived from this group identity can govern team behavior. That is, each member of a group is aware of the expectations others have of him or her, and such awareness influences the choices made. Such behaviors can sometimes be explained by the theory of esteem [BRE00]. Esteem is a "positional good," meaning that one person or organization can be placed above others in a ranking of values, such as trust. The esteem earned by a given action or set of actions is context-dependent; its value depends on how that action compares with the actions of others in a similar circumstance. For example, one corporate chief security officer interviewed by RAND researchers noted that he is motivated by wanting his customers to take him seriously when he asks them to trust his company's products. His esteem is bound to their perception of his products' (and company's) trustworthiness. Jargon is also related to normative expectations. Shared meanings, specialized terminology, and the consonance of assumptions underlying group discussions can lead to familiarity and trust among team members [GUI05]. The jargon can help or hurt decision-making, depending on how a problem is framed. The most frequently cited downside of group decision-making is the tendency in a hierarchy for the most dominant participant(s) to speak first and to dominate the floor. The other group members go along out of bureaucratic safety, groupthink, or because they simply cannot get the "floor time" to make themselves hearda phenomenon known as production blocking. Some groupware systems now on the market are designed specifically for overcoming these potentially negative effects of interpersonal factors in group decision-making [BIK96]. Group behavior extends beyond teams to affect clients, colleagues, and even competitors. Each of these peers can affect the decision-maker as consumer of a good or service when something's value can depend on who else uses it ([COW97] and [MAN00]). We see examples when managers ask about "best practices" in other, similar companies, embracing a technology simply because some or most of the competition has embraced it. In the case of security, the technology can range from the brand of firewall software to the security certification (such as CISSP) of software developers. Credibility and TrustThe number and nature of encounters among people also affects a decision. When information is passed from Jenny to Ben, Ben's confidence in Jenny affects the information's credibility. Moreover, there is an "inertial component": Ben's past encounters with Jenny affect his current feelings. The number of encounters plays a part, too; if the number of encounters is small, each encounter has a "noteworthy impact" [GUI05]. This credibility or trust is important in the economic impact of cybersecurity, as shown in Sidebar 9-3. The Role of Organizational CultureTrust and interpersonal relations are solidly linked to economic behavior. Because interpersonal interactions are usually embedded in the organizations in which we work and live, it is instructive to examine the variation in organizational cultures to see how they may affect economic decision-making, particularly about investments in cybersecurity. We can tell that two cultures are different because they exhibit different characteristics: symbols, heroes, rituals, and values.

These three characteristics make up a culture's practices. It is easy to see that a key motivation for any organization wanting to improve its trustworthiness or that of its products is to build a cybersecurity culturethat is, to embrace practices that make developers more aware of security and of the actions that make the products more secure. As shown in Figure 9-1, values lie at the culture's core. We can think of values as "broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others" [HOF05, p. 8]. This relationship is crucial to understanding cybersecurity's economic tradeoffs: If developers, managers, or customers do not value security, they will neither adopt secure practices nor buy secure products. Figure 9-1. Manifestations of National Culture [Hofstede and Hofstede 2005] A person's personal values derive from family, school and work experiences. From a cybersecurity perspective, the best way to enhance the value of cybersecurity is to focus on work and, in particular, on organizational culture. Hofstede and Hofstede [HOF05] have explored the factors that distinguish one organizational culture from another. By interviewing members of many organizations and then corroborating their findings with the results of other social scientists, they have determined that organizational cultures can be characterized by where they fit along six different dimensions, shown in Table 9-4. The table shows the polar opposites of each dimension, but in fact most organizations fall somewhere in the middle. We discuss each dimension in turn.

These differences are summarized in Table 9-5.

These dimensions affect an organization's cybersecurity economics. The organizational culture, described by the set of positions along six dimensions, reflects the underlying organizational values and therefore suggests the kinds of choices likely for cybersecurity investment behavior. For example:

Companies and organizations invest in cybersecurity because they want to improve the security of their products or protect their information infrastructure. Understanding the human aspects of projects and teams can make these investment decisions more effective in three ways. First, knowing how interpersonal interactions affect credibility and trust allows decision-makers to invest in ways that enhance these interactions. Second, cybersecurity decision-making always involves quantifying and contrasting possible security failures in terms of impact and risk. Behavioral scientists have discovered dramatic differences in behavior and choice, depending on how risks are communicated and perceived. Similarly, people make decisions about trustworthiness that are not always rational and are often influenced by recentness. Tools supporting cybersecurity investment decisions can take into account this variability and can communicate choices in ways that users can more predictably understand them. Third, organizational culture can be a key predictor of how a firm uses security information, makes choices about security practices, and values positional goods like esteem and trust. Each of these actions in turn affects the firm's trustworthiness and the likelihood that its products' security will match their perception by consumers. The behavioral, cultural, and organizational issues have effects beyond the organization, too. Because one firm's security has implications for other enterprises in a business sector or along a supply chain, the interpersonal interactions among colleagues in the sector or chain can affect their expectations of trust and responsibility. Companies can make agreements to invest enough along each link of the chain so that the overall sector or supply chain security is assured, with minimal cost to each contributor. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 171