Tools For Making It Easy

Jointly Explore Barriers

Knowing what to do with an ability barrier is actually fairly simple: Jointly explore the underlying ability blocks and remove them. That s easy. In contrast, knowing how to remove those barriers requires our attention. That means we need to know if others can t do something because of self (they don t have the skills or knowledge), others ( friends , family, or coworkers are withholding information or material), or things (the world around them is structured poorly). But before we consider the ability side of our six-source model, we ll have to break years of bad habits.

Avoid Quick Advice

When we hear that someone faces an ability barrier, we habitually jump in with suggestions. We don t even think about it. We re experienced and we understand how things work, and so when we see a problem, we roll up our sleeves and fix things. It s positively Pavlovian. We see a problem and bing , the gate is up and our tongues are off and running.

When people come to you and explain that they re at their wits end, it s nearly guaranteed that you re going to tell them what to do. After all, they re asking you to tell them what to do. Nevertheless, jumping in with your answers isn t always the smart move.

Should You Do It Yourself?

Let s see how this problem plays itself out. A child brings you a broken toy and you fix it, or at least you try. After all, the child either doesn t know what to do or doesn t have the skills or tools to do it, and so it s obvious that you need to do the work. It s the helpful thing to do. Or is it?

Resourceful problem solvers realize that when others face an ability block, you can either tell them outright what to do (if you know) or invite them to help come up with a solution: What do you think it ll take to fix this? Would you like to help me? Savvy problem solvers choose to work jointly through ability blocks. They fight their natural tendency to jump in with an answer and instead involve the other person. Here s why.

Involvement Both Enables and Motivates

Enables

If you involve others in solving problems, two important things happen. First, you get to hear their ideas. People may not know exactly what to do, but they probably have a good idea about what doesn t work. Actually, they may know exactly what to do but need materials or permission to do it. In any case, start ability discussions with a simple question: You ve been working on the problem. What do you think needs to be done? Ask them for their ideas. Invite them to put their theories , thoughts, and feelings on the table. They ll start to identify the barriers cell by cell .

When people aren t completely certain about what to do or if it becomes clear that they don t understand the situation fully, it s perfectly legitimate to chime in with what you think might help. Of course, how you toss in ideas makes a big difference. Style counts. The feeling of the conversation should be one of partnering. You re working together as intellectual equals, both of you throwing in your thoughts.

Motivate

There s an important secondary benefit to involving others. When people are involved in coming up with a potential solution, they re more likely to be motivated to implement it, and that s important. Consider the following formula:

Effectiveness = accuracy x commitment

Most problems have multiple solutions. The effectiveness of a solution depends on the accuracy of the chosen tactic. That s obvious. It s equally important that the person implementing the tactic believe in it. That s where commitment comes into play.

A solution that is tactically inferior, but has the full commitment of those who implement it, may be more effective than one that is tactically superior but is resisted by those who have to make it work.

Let s be clear about what we re proposing . Many people argue that the reason for involving others is to trick them into thinking the ideas are their own so that they ll work harder to implement them. We re not suggesting that you manipulate people into thinking that your ideas are theirs. Involving others is not a cheap trick. We re simply proposing that other people do have ideas, that getting them out in the open is to everyone s advantage, and that when people are involved in the entire thought process, they see why things need to be done a certain way and are motivated to do it that way.

By involving others, you empower them. You provide them with both the means and the motive to overcome problems.

Start by Asking for Ideas

Involving people is better than merely telling people. But how should you do that? This is quite simple.

Start by asking other people for their ideas. They re closest to the problem; start with their best thinking.

When we first trained people to deal with ability problems, it all seemed so simple. You ask others for their ideas, you get to hear their best thoughts, and they feel empowered. What could be easier? Who could possibly mess this up? As it turns out, there are several ways to go wrong. Here are the top three things not to do.

Don t Bias the Response

As we trained people with these materials over the years, many participants would try to involve the others in resolving an ability problem in the following way:

So you haven t been able to get in touch with the lawyers . Here s an idea: Drive over to their office and wait until they return. What do you think?

People who choose this tactic understand only half of the concept of empowerment. As long as they give the other person a chance to disagree , they feel okay.

Unfortunately, when you re speaking from a power base, offering up your idea first and then asking for the other person s approval misses the mark. You re likely to bias the other person. First, you re filling his or her head with your idea, and this can cut off new thinking. Second, you may inadvertently be sending the message that your idea is what you really want, and so others are not about to disagree with you.

In the example above, the person is likely to say, Perfect, I ll drive across town.

Ask other people for their thoughts; wait for them to share their best ideas, and then, if it is still necessary, chime in with your thoughts. For example, when you are speaking to your teenage son about not clearing two feet of snow from your driveway , he explains that the gas- powered snow thrower is jammed .

You ask, What will it take to fix it? You have an idea but wait to hear what he has to say. He explains that he ran over the Sunday paper and the machine ate it, and now its throat is jammed. From there he explains what it ll take to clear it, what he s doing, and how long it ll take. You offer an idea about a better tool and a way to use it, and together you come up with a plan for what he ll do.

Don t Pretend to Involve

This mistake in involving other people in solving an ability barrier is propelled by two forces. First, you already have an idea and would prefer to implement it without involving others. Second, you believe that you now have to involve others because it s the politically correct thing to do. Here s what you come up with: You simply pretend to involve others by asking for their ideas, after which you subtly manipulate them to come around to your way of thinking.

As you might suspect, this technique comes off as glaringly manipulative. It looks more like sending a rat through a maze and periodically throwing it a pellet for making the correct turn than like a legitimate effort to involve another human being in removing an ability barrier. Here is an example:

What do you think it ll take to get these things out on time? you ask.

How about if we put more people on the job? (You grimace and shake your head.)

I guess I could work overtime myself . (This time you frown deeply.)

I don t know. What if I leave out a few steps along the way?

What did you have in mind? you inquire .

We don t have to shrink-wrap the materials. That ll save a couple of hours.

No, not that. Maybe the paperwork.

I could leave out the billing until . . .

I was thinking of different paperwork, you hint.

How about the environmental reports ?

I love your idea. Delay the environmental stuff, and oh yeah, thanks for coming up with the perfect solution.

People laugh at this script because this kind of thing happens all the time. Some parents practically have a doctorate in this technique:

What would you like to have for dinner? Mom asks.

Mac and cheese! the kids shout.

I was thinking of something with more green in it.

Really old mac and cheese.

Funny. How about something with vegetables? Mom continues.

Mac and cheese with green beans.

Nope, Mom says with a frown. Too starchy. And the endless search for what Mom really has in mind continues.

The problem with these interactions is not that the person in authority had an opinion. These people do have opinions, and they re certainly allowed to share them or even give a unilateral command. That s not the problem. The problem comes when this person attempts to pass off his or her opinions as an involvement opportunity. The sham ends up looking like a game of read my mind and is quite insulting.

Involve others in solving ability blocks only if you re willing to listen to their suggestions.

Don t Feel the Need to Have All the Answers

This mistake is the product of low confidence and a bad idea. Newly appointed leaders are often unwilling to ask their direct reports for their thoughts because these leaders believe that if they don t appear to know everything about the job, they ll look incompetent. In their view, asking for ideas isn t a smart tactic; it s a sign of weakness. When they are facing an employee with an ability problem, the newly appointed do their best to share their insights. The last thing they want to do is query an employee who not only reports to them but obviously needs help.

Of all the bad ideas circulating the grapevine , pretending that leaders must know everything is among the most ridiculous and harmful . Leaders earn their keep, not by knowing everything, but by knowing how to bring together the right combination of people (most of whom know a great deal more about certain topics than the leader will ever know) and propel them toward common objectives.

Confident leaders are very comfortable saying, It beats me. Does anyone know the answer to that? or I don t know, but I can find out.

A couple s version of not involving others takes an interesting turn. We re often unwilling to approach a loved one with a high-stakes problem until we ve come up with the exact solution we want. The uncertainty of approaching a conversation without a bulletproof plan can be terrifying. What if we can t fix it all? What if there is no answer? What if our partner comes up with a really stupid answer? Thus, we think up everything in advance, precluding the other person s genuine involvement.

Completing the conversation in one s head ”before one actually speaks ”nullifies the whole purpose of a crucial confrontation. The idea should be jointly to create shared solutions that serve your mutual Purpose. If you feel compelled to prefabricate answers, consider this: You don t have to make it all better. All you have to do is collaborate. As you develop shared solutions, crucial confrontations become the glue of your relationship; they help you face and conquer common enemies. Don t exclude your partner by developing a plan before you ve even opened the conversation.

Parents struggle with the same issue. Should they hold true to the adage Never let them see you sweat ? Obviously, kids need to know that adults are confident and in charge. They feel secure believing that grown-ups know what to do. So whatever you do, don t ask them for their ideas. It ll freak them out. Still, wouldn t it be better if children learned early on that their parents may be trying their best but don t always know everything?

Get over it. It s okay to ask children for their ideas. They re eventually (say, by age seven) going to know more than you do about all things electronic. Take comfort in the knowledge that you don t have to be omniscient or even semiscient. You ve been around. You bring home the bacon and cook it. You ve been potty-trained for years. Don t worry. You already have enough power and credibility to guilt-trip your kids.

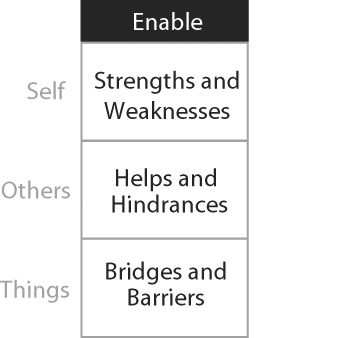

Look at the Six Sources of Influence

Let s assume that after observing someone who has failed to live up to a promise, you carefully diagnose the situation. It s clear that the other person is motivated but can t do what he or she has been asked. You stop, pause long enough to stifle your ingrained impulse to jump in with your best and smartest recommendation, and ask the other person, You re closest to the problem. What do you think needs to be done?

Having asked for the other person s view, it s time for us to return to our diagnostic tool. We need to think through jointly which of the potential sources is at play. We need to listen to the other person s recommendations and then do our best to partner with that person in thinking through the root causes.

This can be tricky. When it comes to motivating others, any single source can overcome all the detractors. You may hate doing your job, your friends may make fun of you for doing it, and your family may offer no support whatsoever, but you need the money. You re motivated. When it comes to motivation, one source is all it takes.

With ability, the opposite is true. Any single barrier can trump all the enabling forces. You know what to do and have the right materials to do it, but you don t have the authority. You re missing only one element, but you re dead in the water. When it comes to ability, since one factor can stop all the other forces in the universe that have joined together to make it possible to do what s required, you d better be good at exploring all possible detractors. Otherwise you could be minutes away from a severe disappointment. You, along with the other person, had better be good at exploring all the existing as well as all the potential ability barriers.

Brainstorm Ability Barriers

Let s assume that the other person is willing to look at the various forces that are making it hard to do what s required. But it s not that easy. He or she s not completely aware of all the forces at play. The two of you will have to brainstorm the underlying causes. And if you want to do that, you need to be good at dealing with ability barriers that stem from self, others, and things.

Self

Brainstorming personal ability issues can be tricky. As we suggested earlier, people often mask inability. They ˜d rather point to other barriers than say they can t do something, particularly if the task is a fundamental part of the job. Make it safe for the other person to talk about personal challenges. Calmly ask about his or her comfort with doing the job, knowledge levels, and other skill factors. Keep the conversation upbeat.

Others

The enabling or disabling role others play is typically easier to discuss. This is about what others are or are not doing, and so it can be less threatening . Nevertheless, when the people you re talking with worry about ratting on their colleagues, they may cover up for their friends by blaming other factors. Once again, make it safe to talk about colleagues and coworkers. Don t use a find the guilty tone. This isn t about blame or retribution; it s about finding and removing ability barriers.

Things

The role the physical world plays is generally the easiest to discuss. People willingly point fingers at the things the company is doing to make their life more difficult ”if they remember to think about them. Remember, human beings tend to forget the role of things in preventing them from achieving what they want to do. People also accept the physical world around them as a given, something that can t be changed: Things have always been this way. Kick-start people s thinking. Ask about everything from systems, to work layout, to policies and procedures.

Three More Hints

As you jointly brainstorm ability barriers, don t forget to ask yourself the following three questions as the discussion winds down.

-

Will this person keep facing the problem? When you are removing ability blocks, you must ensure that the problem won t keep resurfacing. Coming up with a one-time fix is hardly the preferred solution. For instance, the person doesn t have the materials needed. Making a phone call to secure the material solves the immediate problem but doesn t answer the question Will this problem occur again, and why?

-

Will others have similar problems? This companion question explores the need for extending the solution to others. For example, a person doesn t know how to do the job. The two of you come up with a development plan. Will others need a similar plan, or is the problem unique to that person?

-

Have we identified all of the root causes? The ultimate question, of course, is Have you brought to the surface all the forces, fixing them once and for all? For instance, the person needs to take a software course. Why didn t the existing course help? The teacher was ineffective ? Why was that? Japanese executives encourage leaders to ask why five times. We suggest that you probe until you ve dealt with all the elements once and for all.

Advise Where Necessary

Our goal has been to collaborate with the other person in bringing to the surface and resolving ability blocks. We don t want to rush into solutions too quickly or force our ideas onto others. Besides, as we ve argued all along, the people closest to a problem are likely to see more barriers than anyone else can. Nevertheless, there are times when people do need help. They can t see the barriers that have them stymied. In this case, it is our job to teach and advise, to point out stumbling blocks. In short, our job is to make invisible barriers more visible.

Think Physical Features

What kinds of barriers are most likely to remain a mystery to people? As we suggested earlier, most people have a hard time seeing organizational or environmental factors. The things around us are static to the point of becoming invisible. Left to our own devices, we d be the frog in the pot that boils to death because we miss the fact that the heat around us is slowly increasing. We have a hard time noticing subtle forces such as the design of the environment, the availability of tools and technology, the chain of command, and policies and procedures.

For instance, your increasingly estranged relationship with your teenage son may be affected by the fact that he moved into the basement . Now the two of you bump into each other only in and around the vicinity of the refrigerator. Since you re on a diet and he no longer shares a bathroom, you hardly see each other anymore. Be sure the natural flow of the physical world supports your social goals. Think things. Help others see the impact of the physical world.

In a similar vein, it can be helpful to encourage people to identify the various bureaucratic forces that are preventing them from doing what needs to be done. With time and constant exposure, people start to accept rules, policies, and regulations as a given. They start treating them like commandments or laws of nature. Soon these highly constraining walls of bureaucracy become invisible.

Make them visible. Play the role of ignorant outsider. Keep asking, Why can t we do that? If a policy is no longer relevant, do away with it. If a rule is excessively constraining, treating people as if they can t be trusted, secure permission to release the constraint. Every time someone passes a new company rule, you can bet it s in response to someone making a bad choice. Now everyone is restricted from ever making a choice:

Listen up, folks. Roberta broke the law yesterday , so we ll all be going to jail.

Keep in mind that rules and policies don t solve everything and that the ones you make in-house you can unmake.

If you really want to help people identify hidden barriers, attack the paperwork. Look at forms and signatures as targets for change. If people can t complete their jobs on time because it takes seven signatures to get started, revisit why the signatures are required.

One company cut their response time in half by reviewing such a policy. The typical customer-service response couldn t begin until seven people signed off on a form. This was the liberating idea: Typically, three of the people needed to give approval, but four only needed to be informed. Allowing employees to act after three signatures and then routing the form to the other four after the fact rocked their world.

By all means give people easy access to the information they need to make the right choices. Make sure that from the mass of data that s out there, the right data are in front of the right people at the right time. For example, quit complaining that your daughter isn t following her diabetes regimen if she s cut off from the data that would encourage her to do the right thing (her various blood sugar levels and the consequences of each one). You can harangue. You can beg. Or you can put numbers and charts in front of her.

Here s another helpful tool. To help surface all variables , ask, If you ran this place, what would you do to solve this problem? Asking people to assume the role of the big boss can be extremely liberating. Freed from the shackles of thinking from within their own fields of influence, they begin to look for ways to remove every company-made barrier.

In short, think hidden forces, think lots of forces, and keep at it until you re satisfied that you ve wrestled every single barrier to the ground.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 115