BUDGET

Once you have completed the macro plan the next step is to produce a budget for the project. At this stage this means producing a coarse budget with an accompanying sensitivity analysis.

The budget plan is often thought of as the budget statement and it is based on the task, resource and timescale estimates that were previously completed to enable the production of the macro plan. As with the task estimating, the objective is to produce a coarse estimate rather than a very accurate estimate. This enables you to go quickly and present the budget for approval in principle sooner.

Building a project budget is a mechanistic task. However, it does demand a methodical and thorough approach from you or whoever will be responsible for its production. Trying to cut corners to speed the process up will normally result in disaster.

The first step is to work out all the relevant costs that can be associated with the tasks defined so far. The identified costs should be split into capital and revenue costs. Capital costs are those that occur on a once-off basis - for example buying a software program. Revenue costs are those that occur on an ongoing basis - for example the maintenance of the software program.

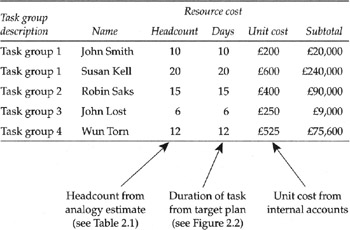

Normally the largest revenue cost for a project is the staff cost. Calculating this cost first helps to put the other revenue costs into perspective. If they are less than 1 per cent of the staff costs it is not worth spending a significant amount of time calculating them. To make the cost calculation easier it is useful to set up a spreadsheet. A sample spreadsheet is shown in Table 2.2.

|

Most of the information required to populate the table will already have been gathered. It is likely that for any given task there will be more than one person working. This is shown in Table 2.2 for task group 1. By simply inserting an extra line in the table you can easily add resources. This method can also be applied for people who are working for the same length of time but have different unit costs.

In addition to identifying the task-based costs you must also identify the capital costs for the project. This should also be done on a task-by-task basis. At this early project stage it is likely that many of the capital costs will be unknown and as a result the costs will be best guesses. A simple way to improve the guess of the cost is to use a three-point estimation technique. This is simply a repetition of the method used earlier for estimating task resource needs. A sample table is shown in Table 2.3.

| Cost description | Analogy | Best case | Most likely | Worst case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||

| Analogy code: DB - done this or similar before | ||||

You need to judge which costs you should use. So as with the resource estimates you should assess the estimators using the analogy criteria. With an assessment of the estimators you should be able to determine which costs to use. Once you have determined the costs you should collate them with the resource costs into a table like the one shown in Table 2.4.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task description | R | C | R | C | R | C | R | C | R | C | R | C | R | C | |

| Total | |||||||||||||||

| R - revenue C - capital | |||||||||||||||

The table shows a month-by-month timescale. This timescale was arbitrarily chosen and should be changed to fit with the overall length of the actual project concerned . In most cases months will be the minimum time period that should be used. It is more likely that quarterly or six-month periods will be appropriate for an advanced project. Each time slot is split into two parts , the revenue costs and the capital costs. These costs are totalled at the bottom of the columns . This total is then the total expenditure per month or per quarter depending on the time period used.

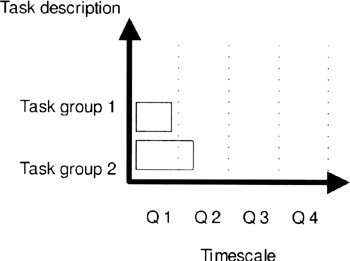

Once the costs have been attributed across the various months it is likely that there will be cost scheduling issues. This is illustrated in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Distributing the costs

Figure 2.3 shows two tasks. The costs associated with the first task are all contained in the first quarter. However the second task, task group 2, is split across quarter 1 and quarter 2. You need to decide whether the cost gets written up in the first quarter, the second quarter or apportioned between the quarters .

The simplest way of dealing with the cost is to attribute it on a straight-line or linear basis. This is achieved by dividing the total cost for task group 2, by 4, the period over which the task runs. If the total cost for task group 2 is 40,000 then this means that 10,000 is spent per month for four consecutive months. This means that 30,000 is attributed to the first quarter and & pound ;10,000 is attributed to the second quarter. In most cases this method is sufficient. However, in some cases it is necessary to model the cost for the task.

Modelling costs can be complicated. However, at this stage simplicity is always better since the planning is still at a coarse level. Modelling costs should only be used when the cost is obviously not spent in a linear manner, for example when there is a large payment due at the start of the task perhaps as part of contract signing. As the planning progresses, more and more sophisticated models can be used. It is likely that you will have both linear and modelled costs. These should be added together and put into a table like the one shown in Table 2.5.

| Quarter | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost description | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| Linear costs | |||||

| Modelled costs | |||||

| Total | |||||

This table shows the total costs per quarter for the project. This shows the total spend that the project requires to make in the given time period and therefore the amount of funding the organization needs to supply, a key ingredient for the business case.

Contingency

Before finalizing the budget, additional cost should be added for contingency. Contingency is the addition of funds to the project budget to allow for tasks becoming more expensive than originally planned. This can occur where project tasks run late or where they are underestimated or the external supplier costs more than expected.

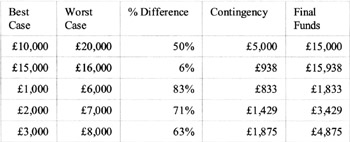

One method of calculating contingency is to assume that all costs used in the budget preparation are the most likely costs. This then allows a mechanistic method of calculating the contingency on a task-by-task basis. This is achieved simply by: 1 ˆ’ (best case / worst case) — best case. The sum of this calculated cost and the most likely cost is the contingency-adjusted figure. This figure accounts for the difference between the best case and worst case scenarios. This is illustrated in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4(a): Contingency calculation

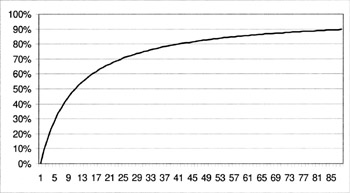

The table in Figure 2.4(a) shows that a large difference between best and worst case returns a high contingency. Conversely when the difference between the best case and worst case is low the contingency figure is lower. This can be illustrated by the curve in Figure 2.4(b). In the figure the initial slope of the curve is steep and the end of the curve is shallow . Effectively the calculated result is normally close to the most likely figure for the work. This means that excessive amounts of contingency are not added unless the worst case and best case estimates vary enormously.

Figure 2.4(b): Contingency weight attribution

The main difficulty with using this method for calculating contingency is its reliance on the use of the best case estimate. It is really only appropriate to use this when the task estimate is based on or close to the best case or most likely case estimate. Often project managers will use worst case figures where they believe the task risk is high. In these cases the calculation for contingency will not work.

An alternative method of calculating contingency is simply to add a 5 per cent or 10 per cent allowance on top of the total project budget requirement. This pragmatic approach often produces a very similar result to the more technical and mechanist approach.

Reserve

As well as adding contingency to the budget you should also add a project reserve. Reserve funds are included for coping with forgotten areas of spend. The amount you should set aside depends greatly on the type of the project that you are managing. If it is a completely new project and the work is unknown then setting aside a very large reserve is advisable. Projects such as the Channel tunnel or the baggage handling system at Denver airport both overran their initial budgets by more than 100 per cent.

If it is a project that is similar to one undertaken before then the amount set aside should be a lot less. In some cases it is acceptable not to set aside any funds. Instead anything that is forgotten is sought from the organization's normal operating funds. It should now be possible to construct a final budget. The final budget consists of the calculated cost for revenue and capital, the contingency cost and the reserve cost.

Once the budget is complete you should be able to start producing the business case for the project. You should now have all of the information necessary to enable you to pull together a compelling business case.

Business case production

Leaving the approval of the business case until this point in the planning can make project managers uncomfortable. Many project managers would hope to write and get approved their business case at the start of the project. However, business cases approved early on in the project life cycle often are only approved in principle and generally they need to be continually revisited as the project progresses.

Leaving the production of the business case until this stage in the project enables you to use the information developed so far in the business case material. This material is built on firm ground and will have been worked through with the steering group. Practically this means that the steering group members will be happier to approve the business case fully.

The style and format for the business case will vary from organization to organization. Whenever possible you should use the organization's style, thereby avoiding duplication of existing work. However, regardless of the template, in almost all organizations two basic questions will remain at the heart of the business case: 1) What is going to be done? 2) What is the commercial justification for doing it?

What is going to be done?

Writing the first part of the business case is something that either you or the project sponsor should undertake. Writing this part of the business case should be relatively straightforward since all of the information needed is already available from the macro plan. This presents the requirements and timescales in a coherent fashion and it is often called the ˜project strategy'. Many organizations will have a prescribed format for this part of the business case. However, as with many areas of work in advanced projects it is also likely that no template will be available. When this happens you should adopt a simple format.

The first area to present is a written summary of the project's aims and objectives. This should concentrate on the commercial value of the completion of the project. If you are writing the material you should present it in an overview manner. The presentation should explain what will be done, why it is commercially justified and how much it will cost. This should be between 200 and 400 words in length. If the project cannot be summarized in this volume of words then the project is not properly understood . Skilled project managers should always be able to summarize their project simply - they will have to do this many times as the project progresses.

Once the initial summary is written then the second area to include is a presentation of the scope of the project. It is not necessary to present all of the tasks from the brainstorm meeting or the senior managers' wish lists. Whilst this material is relevant it should be relegated to an appendix to the plan. What should be presented is the main task groups and, in detail, a description of any task that you consider to be high-risk. You can identify high-risk tasks from the analogy estimation carried out as part of the task and cost estimations. The high-risk tasks are those that have been identified as not done (ND) before.

What is the commercial justification for doing it?

Once you or the project sponsor have written the scope section of the business case you need to produce part two, the commercial justification. Producing the commercial justification is normally the project sponsor's responsibility. However, the majority of the work on this area will have been completed either by you or by the finance department. As a result, the project sponsor will need significant help in producing this section of the business case.

Normally the commercial justification presents the proposed cost estimates for the project and accompanies them with a project revenue stream that will result at the completion of the project. This enables a cash flow to be determined and an investment decision made. The cash flow and the investment part are normally dealt with by the finance part of the organization rather than the project.

The project normally presents the cost basis for the project. It can be tempting to present the costs using a copy of the tables already developed (eg the cash flow). This should be avoided. The purpose of the presentation is to give an overview of the costs, not a detailed account of them. As with the task summary, the detail should be presented in an appendix. The best way to present the resource and budget requirements of the project is to start from the broadest level. This means saying the project will take x years and cost between y and z. Many project managers leave this statement until the end of the justification. They feel the correct way to present the cost is to build up to this statement rather than state it at the start. They are wrong. Stating the overall cost in the opening section is the right way of managing the readers. If you do not do this, the first thing readers will do is flip forward until they find the figures that they are looking for. By building from the top down, readers are encouraged to build understanding. The simplest way to validate this approach is to consider what you would say if someone told you figures in this way. A general format would be:

The project will take x months to complete and will require between z and v in funding.

z is the lower-risk estimate and is calculated on the lowest resource and capital expenditure estimates. See Appendix Z.

v is the higher-risk estimate and is calculated on the highest resource and capital expenditure estimates. See Appendix Z.

The tasks with the widest cost range are:

X

min cost

max cost

Y

min cost

max cost

Business case approval

Once the business case is complete the next step is to seek formal approval for its implementation. Surprisingly it is not always clear who has the approval authority for an advanced project's business case. This applies equally to organizations that have properly documented procedures and those that do not have them. Advanced projects are not like other projects. Organizations do not undertake many of them in the course of a year. Often they involve a complicated move in strategy for the organization, something that does not happen particularly often. The small frequency of occurrence means that procedures to cover the eventuality are often not produced. Where there is a lack of process you need to rely on the steering group that you have already formed . You should seek approval from them for the business case and the associated plans.

It is likely that your steering group will already include a director or someone very senior in the organization. When you take the business case forward you should also ensure that you have added any technical and business authorities. You should also assess if there is another project relying on the use of the same resources as your project. If there is then that project manager should also be invited. This serves two purposes. Firstly, it ensures that any conflict is brought into the open where it can be dealt with effectively. Secondly, it's always good practice to have another peer review the plans that you have produced. Hopefully, the other person can add value by suggesting areas for improvement.

Often the approval meeting can become long and tedious . Participants get weary and the result is a very poor start for the project. This should be avoided. You should prepare the approval session well in advance. The simplest way to do this is to brief the proposed attendees before the meeting. This should be on a one-to-one basis and it should give you an opportunity to understand any potential disagreements that might exist. It is also an opportunity for finding and developing possible solutions that would be acceptable.

Once all the members of the steering group have been canvassed for their views in one-to-one meetings then the business case should be updated. This updated version of the plan should take account of difficulties or problems found and it should be sent out to the steering group members. Once the members have had a short time to review the material the steering group should meet to review the business case for approval. At the meeting the business case should be presented. This presentation should include a commentary of the key issues and their proposed solutions.

If it is difficult to carry out one-to-one reviews then an alternative is to use a paper review. A paper review involves sending to each of the steering group meeting participants the macro plan and a comment sheet. The comment sheets are gathered together and analysed, and the document is iterated. After several iterations the business case is normally pretty complete and the steering group can be called together.

It is worth sounding a note of caution about this approach. Whilst this might seem an attractive approach it does prove to be less focused and less fruitful than one-to-one meetings. Reviewers comment on the quality of the English rather than the substance of the document. It is only when they get to the meeting that they start really to discuss the essence of the business case.

Whatever method is chosen, the purpose of the review is to get the organization behind the project. This is the sole objective that you should have in mind when running the meeting. Project managers often find it difficult to remain dispassionate about their projects. They want to argue down dissenting voices, not promote them into being considered . However, it is much better to hear and deal publicly with the views than to have them aired privately behind your back. Your role is to ensure that all points of view are heard and dealt with effectively - even the negative ones!

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 69

- Chapter I e-Search: A Conceptual Framework of Online Consumer Behavior

- Chapter III Two Models of Online Patronage: Why Do Consumers Shop on the Internet?

- Chapter XIII Shopping Agent Web Sites: A Comparative Shopping Environment

- Chapter XVII Internet Markets and E-Loyalty

- Chapter XVIII Web Systems Design, Litigation, and Online Consumer Behavior