163 - Posterior Mediastinotomy

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Mediastinum > Section XXIX - Primary Mediastinal Tumors and Syndromes Associated with Mediastinal Lesions > Chapter 193 - Mediastinal Parathyroid Adenomas and Carcinomas

Chapter 193

Mediastinal Parathyroid Adenomas and Carcinomas

Ann-Greth Bondeson

Norman W. Thompson

The first documented excision of a mediastinal parathyroid adenoma occurred at the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1932 when Charles Martell, a sea captain, underwent his seventh operation for persistent hyperparathyroidism. Although a small portion of the adenoma was left in place and another portion transplanted, he developed tetany that required intravenous calcium replacement. Bauer and Federman (1962), however, recorded that unfortunately, 6 weeks later, following removal of an obstructing ureteral stone, he died as a result of persistent hypocalcemia. More than half a century later, ectopically located parathyroid tumors in the mediastinum still can be a challenge and a severe test to both surgeon and patient. We will consider the current knowledge of the diagnosis, localization, and surgical management of mediastinal parathyroid tumors.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

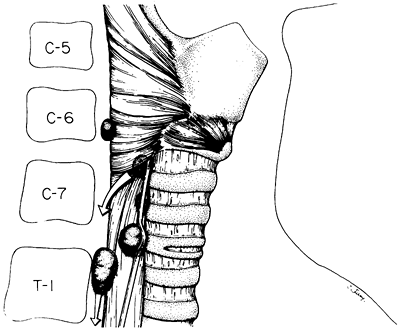

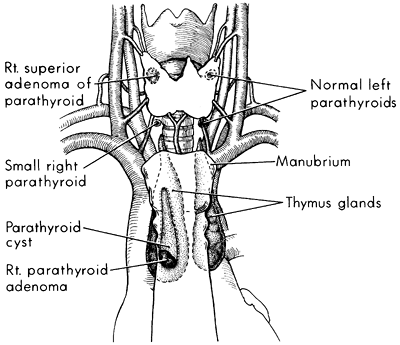

The reported incidence of mediastinal parathyroid tumors has varied considerably, ranging from a low of 1% to 2% to as high as 14% to 20%. This is because some researchers, such as Dubost and Bouteloup (1988), have considered all parathyroid glands located caudal to the cephalic border of the sternum as mediastinal, whereas Rothmund (1976) and Wang (1986) and their associates, as well as others, have included only those inaccessible during a cervical exploration. Because exploration of the upper thymic poles is currently considered routine for a missing inferior gland and will expose the majority of adenomas above the level of the aortic arch, we will consider in detail only those tumors in the deep mediastinum that are inaccessible to routine cervical exploration. These are the tumors that, even with excellent technique, require a median sternotomy to locate and excise them. They account for no more than 1% to 3% of all parathyroid tumors and with few exceptions, as one of us (NWT) and associates (1982) noted, represent inferior parathyroid glands whose abnormal embryologic descent has resulted in their ectopic location. They may be the only inferior gland on the side of their adult location or represent a supernumerary gland on that side. In nearly all cases, the arterial supply to a deep mediastinal tumor is also ectopic. Most frequently, it arises from a branch of the internal mammary artery. In contrast, cervically accessible upper mediastinal parathyroid glands usually have a blood supply arising from the inferior thyroid artery. The rare exceptions to these definition guidelines are parathyroid tumors found in the visceral compartment of the mediastinum whose embryologic origins are not clearly determined. Paraesophageal or retroesophageal parathyroid tumors, without known exception, always arise from enlarged superior glands that have mechanically descended into their acquired location (Fig. 193-1). A normal cervical blood supply is maintained from a branch of the inferior thyroid artery. These glands are not considered embryologically ectopic. Furthermore, they can always be excised during a neck exploration, providing that the surgeon is aware of this possibility. Finally, it should be noted that on occasion, even an ectopically located deep mediastinal parathyroid tumor can be removed through a neck excision if it is contained within a thymus gland that can be mobilized with careful traction from above. On at least three occasions, we have been able to excise parathyroid adenomas from positions well below the aortic arch by this method, obviating the need to perform a median sternotomy (Fig. 193-2). In one patient, the mediastinal tumor was a second adenoma arising from a supernumerary fifth gland and was excised during a cervical reexploration of the thymus prior to an anticipated median sternotomy (Fig. 193-3). The thymus had not been mobilized previously because three normal glands and an adenoma were found at the first exploration.

|

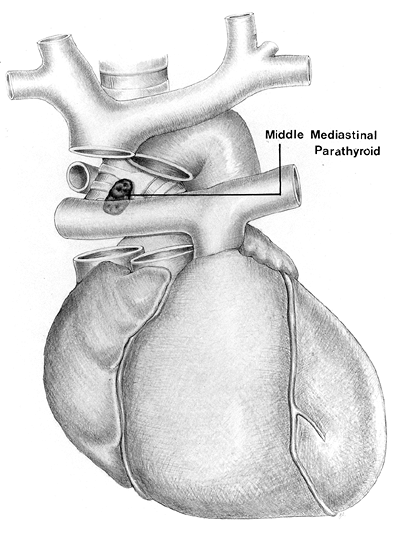

Fig. 193-1. Artist's drawing of ectopic locations of superior parathyroid adenomas. Those migrating along or posterior to the esophagus do so in the prevertebral space and can always be excised from the neck because their vascular pedicle arises from the inferior thyroid artery. From Thompson NW, Eckhauser F, Harness J: The anatomy of primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 92:814, 1982. With permission |

P.2813

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

With few exceptions, mediastinal parathyroid tumors are first considered after a failed cervical exploration for hyperparathyroidism. However, McHenry and associates (1988) reported several cases in which mediastinal adenomas were identified by one or more imaging techniques prior to operation and led directly to a mediastinal exploration in critically ill patients in whom the first operation had to be curative. Because deep mediastinal tumors are so uncommon (1% to 3%), most surgeons would not recommend localization studies prior to a routine cervical exploration for hyperparathyroidism. Such studies are not considered to be cost effective, and negative results do not rule out the presence of an ectopic adenoma.

|

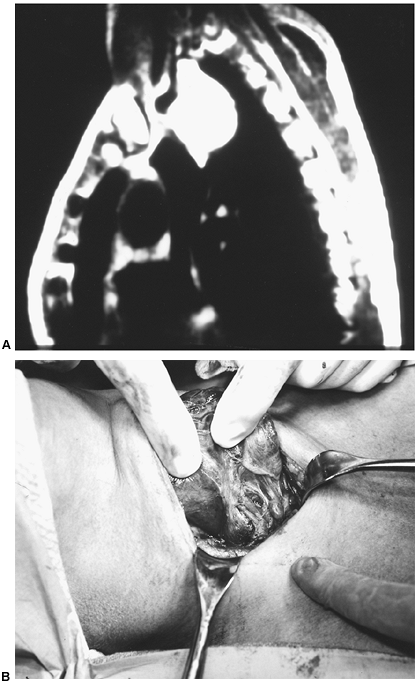

Fig. 193-2. Operative findings in a 27-year-old woman with a 3-cm parathyroid adenoma in caudal thymus teased from cervical incision. The adenoma was at the level of the pericardium, about 13 cm below the sternal notch. Note well-developed thyrothymic tracts still attached to lower poles of thyroid on both sides. Usually adenomas at this level require median sternotomy for excision. |

|

Fig. 193-3. Artist's drawing of a cystic parathyroid adenoma within the thymus that was excised by cervical thymectomy during a reoperation for persistent hypercalcemia despite identification of three normal glands and excision of an adenoma at initial operation. |

Localization of missing'' parathyroid tumors in the deep mediastinum can be achieved by a variety of imaging techniques, although no single study or combination of studies approaches 100% sensitivity because of false-negatives and false-positive results. Therefore, such adjuncts do not eliminate the need for thorough knowledge of parathyroid embryology, which is discussed in Chapter 156.

The most important first step before undertaking a reoperation in the mediastinum is to analyze the operative notes and pathology report from the previous exploration or explorations to determine whether the missing'' gland is most likely to be superior or inferior in origin, because that simple fact can determine where the search should be directed. If four normal glands were previously identified with certainty and the patient has biochemical proof of hyperparathyroidism, the disease is most likely due to a supernumerary gland tumor in the mediastinum. If an inferior gland was not found after a thorough exploration, including intrathyroidal, carotid sheath, and upper thymic locations, the tumor is assumed to be in the deep mediastinum. As reported by Dubost and Bouteloup (1988), as well as by Dubost (1984),

P.2814

Proye (1988), and one of us (NWT) (1982) and associates, approximately 80% of all deep mediastinal parathyroid tumors are located in the anterior mediastinum and are usually situated within or in close contact with the thymus.

Inferior gland tumors arise from parathyroid tissue that has been embryologically displaced. This occurs likely because of the common origin of the thymus and inferior parathyroid gland from the third branchial pouch. It is emphasized that most parathyroid tumors within the anterior mediastinum can be reached from the neck and do not require sternotomy for removal. In most individuals it is possible to tease out 5 to 10 cm of thymus, even when the gland is atrophic. In some younger patients (see Fig. 193-2), the entire thymus may be removed and parathyroid tumors as caudad as the pericardium may be successfully excised. Gentle handling is important because rupture of the fragile capsule of the thymic remnant in older patients makes application of cephalic traction without disruption of the entire gland impossible. Often, the intrathymic parathyroid tumor can be felt between the fingers before being teased into view. As noted, the majority of mediastinal tumors are intimately associated with the thymus. In Russell and associates' (1981) series of 37 parathyroid adenomas removed from the anterior mediastinum, 26 were associated with the thymus, whereas 2 were attached to the pericardium and 9 were behind the thymus in proximity to the aortic arch. Similar experiences have been reported by Rothmund (1976) and one of us (NWT) (1982) and our respective associates. One of us (NWT) (1978) and co-workers (1982) have noted that parathyroid tumors of the superior glands migrate into the upper posterior part of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum in approximately 40% of cases. The larger the tumor, the more likely this is to occur, and this probably results from a combination of factors, including gravity, deglutition, negative chest pressure, and an unobstructed pathway into the prevertebral space. When a superior parathyroid gland is not easily found in the neck, an exploration of the prevertebral space is always indicated.

The areolar tissue and fascia to the prevertebral fascia level is incised lateral to the upper third of the thyroid lobe, allowing a finger to be inserted under the inferior thyroid artery trunk down into the posterior portion of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum (Fig. 193-4). By this maneuver, a tumor in this location can be identified, gently manipulated with traction from above and pressure from below, brought up into the field of vision, and its vascular pedicle from the inferior thyroid artery ligated. In our experience, all superior gland adenomas in the posterior portion of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum (para or retroesophageal in position) can be excised by this technique through a cervical approach.

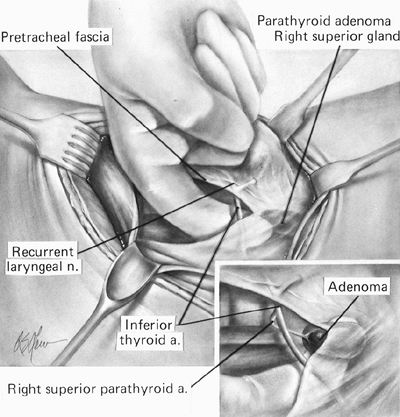

Sarfati (1985), Curly (1988), McHenry (1988), and Proye (1988) and their associates reported that the most difficult parathyroid tumors to localize and excise are those arising in the central portion of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum. Although previously considered extremely rare, they are being reported with increasing frequency, primarily because of their detection by imaging techniques such as that reported by McHenry and colleagues (1988). Curly and associates (1988) have reported that the two most common sites where these lesions have been detected are the aortopulmonary window (Fig. 193-5) and in close proximity to the right pulmonary artery near the tracheal bifurcation or slightly to the left on or above the left main-stem bronchus (Fig. 193-6). The occurrence of such lesions is difficult to explain on an embryologic basis, and it is not known with certainty whether their origin is from an inferior or superior gland. An inordinately high percentage of these tumors have been fifth glands, found after four normal glands were initially found at cervical exploration. Embryologic fragmentation of either parathyroid III (inferior) or IV (superior) can occur, but at the 7.5- to 11-mm embryo stage, parathyroid IV tissue could develop in the proximity of the future right pulmonary artery and thus remain in the visceral compartment (the middle mediastinum). Regardless, these ectopic tumors will be impossible to find unless specifically sought. Cohn and Silen (1982) reported that in one case, a 4-cm adenoma in the aortopulmonary window was finally discovered after 10 previous cervical and 3 mediastinal explorations.

|

Fig. 193-4. Artist's rendering of the technique used routinely in exploration for an enlarged superior gland. Note that the fascia has been divided so that a finger can slide along the prevertebral fascia within the avascular space dorsal to the inferior thyroid artery down into the prevertebral space of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum. |

Because parathyroid tumors may develop within the visceral compartment (the middle mediastinum), failure

P.2815

to identify a tumor within the anterior mediastinum now necessitates extension of the search to include the aortopulmonary window and the remainder of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum, even though these areas may be difficult to explore through a median sternotomy.

|

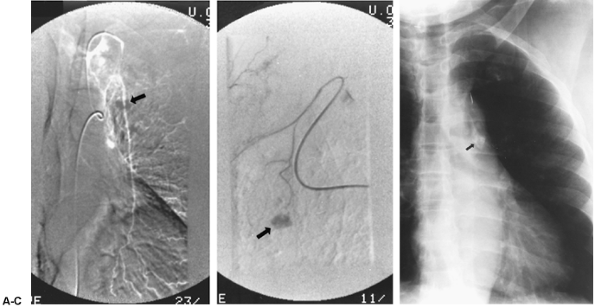

Fig. 193-5. A. Selective left internal mammary arteriogram in a 56-year-old man who had suffered with multiple ureteral stones for 10 years. Two previous cervical and one mediastinal exploration had failed. Serum calcium was always below 11 mg/dL. The arrow points to a small adenoma located in the aortopulmonary window. This site was suggested by the radiologist after reviewing the films, which included lateral and oblique viewers. B. Artist's drawing showing the location of the adenoma (same case as in A). This was excised through a left anterior thoracotomy, which was used because of a previous median sternotomy. From Curley IR, et al: The challenge of the middle mediastinal parathyroid. World J Surg 12:818, 1988. With permission. |

|

Fig. 193-6. Artist's drawing showing a common location for the uncommon middle mediastinal parathyroid adenoma in the visceral compartment. Although difficult to expose through a median sternotomy, this location can be visualized after careful mobilization of the great vessels. From Curley IR, et al: The challenge of the middle mediastinal parathyroid. World J Surg 12:818, 1988. With permission. |

LOCALIZATION STUDIES

All patients who have had a failed parathyroid operation should undergo preoperative localization procedures before proceeding with another exploration, particularly if a mediastinal procedure is anticipated. Rothmund (1976), Edis (1984), Norton (1985), and Wang (1986) and their associates reported the failure rate for mediastinal exploration to be 30% to 36% in those cases in which localization studies have not identified a tumor before undertaking the operation. Noninvasive imaging studies are also indicated before an initial cervical exploration in patients who are in hypercalcemic crisis, because a mediastinal exploration must be seriously considered if the disease is not found in the neck.

P.2816

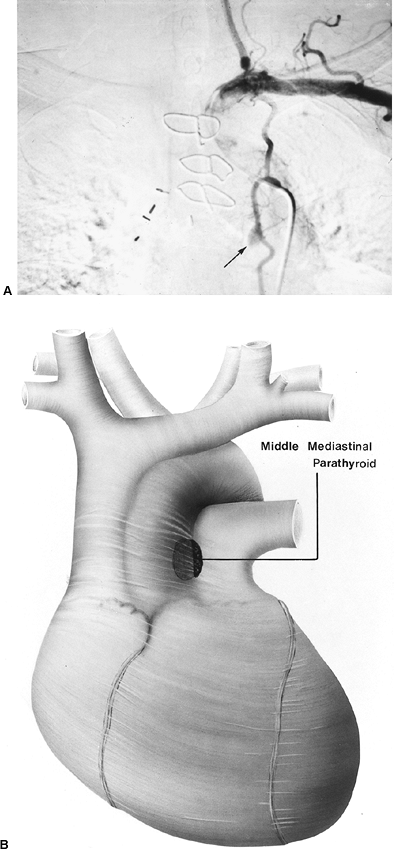

As Levin and colleagues (1987) have noted, in this urgent situation, localization study results are usually positive because of the large gland or glands present and may confirm the suspected diagnosis when biochemical studies are still pending (Fig. 193-7).

The two most commonly used imaging techniques for mediastinal parathyroid tumors are computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 193-8) and technetium 99m sestamibi [99mTc methoxyisobutylisonitrile (MIBI)] scintigraphy. The value of these studies has been pointed out by Norton (1985), Sarfati (1985, 1987), Levin (1987), Curly (1988), and McHenry (1988) and their associates, among others. Rubello and colleagues (2002) have suggested a single-day imaging protocol of 99mTc pertechnetate-MIBI subtraction scintigraphy and MIBI single-photon emission computed tomographic (SPECT)/CT image infusion for localization of mediastinal parathyroid adenomas. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging has also been used with increasing frequency. However, these noninvasive techniques have been successful in identifying only about half of all subsequently proven mediastinal tumors present. Doppman and colleagues (1996) found that the rare parathyroid adenoma in the aortopulmonary window could be differentiated from the more common anterior mediastinal tumor with SPECT scanning in 100% of patients (six of six) when the results of 99mTc sestamibi scintigraphy were positive. This compared with positive results of 89% with CT and 63% with MR imaging studies. This precise localization is of utmost importance, particularly when we are advancing to thoracoscopic techniques. When these techniques have failed to demonstrate a missing'' parathyroid tumor, selective venous sampling using the intact serum parathyroid hormone immunoradiometric assay is the next indicated study. This study may or may not be helpful, but usually will regionalize the source of hormone to the mediastinum if a tumor is present there. Selective arteriography is reserved for those cases in which all other studies have failed

P.2817

and the surgeon is certain that the parathyroid tumor is not in the neck. This procedure has been associated with significant neurologic complications (2%) and should be limited to the internal mammary arteries, avoiding as much as possible any manipulations near the orifice of the vertebral arteries. In addition to identifying an otherwise occult tumor, the procedure may be modified as a therapeutic alternative by injecting hypernormal contrast material into the tumor. When this can be accomplished, the artery is then embolized with fibrin or a small metal coil. If a mediastinal tumor has a single feeding artery and the contrast material is retained within the adenoma, infarction of the adenoma is likely to occur, resulting in alleviation of the hypercalcemia (Fig. 193-9) without the need for a mediastinal exploration. Doherty and colleagues (1992) reported a 60% success rate following angiographic ablation of mediastinal parathyroid adenomas and no major complications. These patients are at an increased risk for developing permanent hypoparathyroidism, because no tissue is preserved for implantation. There is also no tissue available for histopathologic examination. We recommend that this technique be reserved for patients with an increased surgical risk and at least one normal parathyroid gland remaining in the neck.

|

Fig. 193-7. A. MR imaging, lateral view, showing huge 6 5 cm hyperplastic parathyroid (HPT) in the prevertebral portion of the visceral compartment of the mediastinum. This 65-year-old woman was admitted in hypercalcemic crisis. Imaging confirmed the diagnosis of HPT and allowed for urgent neck exploration as soon as the calcium level had been lowered from 18 to 12 mg/dL. B. Operative findings in the same patient as in A. The techniques used were as in Fig. 193-4. After retracting the right thyroid lobe medially and opening the fascia to the prevertebral space, gentle finger dissection and further retraction exposes the cephalic end of the large gland just under the inferior thyroid artery. Note the 1.5-cm inferior parathyroid gland anterior and caudal to the artery. This patient had asymmetric hyperplasia. A subtotal parathyroidectomy was performed, leaving 50 mg of viable tissue. |

|

Fig. 193-8. CT scan enhanced with contrast injection shows anterior mediastinal parathyroid adenoma at the level of lower border of aortic arch. The arrow points to an adenoma. A previous cervical exploration had failed to identify a right inferior gland, despite a partial thymectomy. The adenoma was posterior to the thymus and adherent to the ascending aorta when removed through a median sternotomy. |

|

Fig. 193-9. A. Selective left internal mammary arteriogram shows a 2-cm parathyroid adenoma in a 72-year-old woman who had undergone two previous cervical explorations. The arrow points to the adenoma. B. Super selective contrast injection into the mediastinal parathyroid adenoma (subtraction film) was followed by injection of embolizing coils to occlude the parathyroid artery. C. Chest radiograph 24 hours after contrast injection and embolization, showing contrast material still present. This patient became normocalcemic and remained so for 2 months following the procedure. Arrows point to the adenoma. |

PATHOLOGY

Benign Adenomas and Hyperplasia

The pathology of mediastinal parathyroid lesions does not differ from that of cervical parathyroid glands. Solitary adenomas predominate, and secondary hyperplasia of an ectopic parathyroid gland is less common. Primary adenomas are generally small (2 to 4 cm), although lesions larger than 5 cm have been reported, such as those by Dieter (2002) and Batsakis (2001) and their associates.

Hyperplasia affects mediastinal parathyroid glands to the same extent as it does glands in normal locations. A supernumerary gland, occurring in approximately 15% of patients with hyperplasia, is found in the anterior mediastinum in more than 50% of cases. Because such glands are usually within the upper thymus, cervical thymectomy has become a routine part of the surgical treatment of both primary and secondary hyperplasias.

Regardless of whether the surgeon is intending to perform a total parathyroidectomy and autotransplantation or subtotal parathyroidectomy, adenomas may develop in supernumerary glands as well. However, thymectomy is performed routinely only when four normal glands have been

P.2818

identified or an inferior gland has not been detected after finding three other normal glands.

Linos and colleagues (1989) reported that occasionally a hyperfunctioning parathyroid gland may assume the appearance of a large cyst in the mediastinum. In Calandra and associates' (1983) review of parathyroid cysts, 50% were associated with hyperparathyroidism and the majority (90%) were located in the neck. A literature review by Guvendik and associates (1993) identified 18 mediastinal parathyroid cysts. Only 4 (22%) were associated with hyperparathyroidism. However, Shields and Immerman (1999), in a more recent review of mediastinal parathyroid cysts, identified 94 patients including our own case report with such cysts. Thirty-nine patients (41.4%) had functioning cysts (i.e., associated with hypercalcemia). In an addendum to their report, two additional case reports of a patient with a nonfunctioning cyst were published by Hattori (1998) and Shibata (1998) and their associates after the closing date of the aforementioned review (see Chapter 197). For reasons unknown, the cyst occurs more commonly on the left side, although the largest cyst that we have encountered developed in a right-sided supernumerary gland that was a second adenoma in the patient. The 8-cm cyst was entirely within the thymus and extended caudally to the pericardium but was teased out of the mediastinum from a cervical incision at a reoperation for persistent hypercalcemia (see Fig. 193-3). The cyst fluid has markedly elevated levels of parathyroid hormone. This can assist in diagnosis if a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is performed. Radionuclear scintigraphy also has been useful in determining if a mediastinal cyst is of parathyroid origin. Biopsy of the cyst wall is often not helpful because the parathyroid tissue is not homogeneous; rather, the cyst wall contains multiple nests of parathyroid tissue. It is controversial whether these cysts are the result of cystic degeneration of a parathyroid adenoma or a separate entity (see Chapter 197).

Other morphologic variants include partially calcified adenomas, which are uncommon but noteworthy because they can be seen on plain chest radiographs. All calcified nodules in the mediastinum are not granulomas; when a single calcified nodule is found in the anterior mediastinum in a hypercalcemic patient, an adenoma should be suspected. It has been our experience that large adenomas with calcification have contained other areas of hemorrhagic necrosis and scarring. Some of these adenomas have been associated with a surrounding desmoplastic reaction, evidently induced by an inflammatory reaction in the capsule. These adenomas have been found in both the neck and the mediastinum and can be initially misinterpreted as parathyroid carcinoma because of their capsular thickening and local adherence. However, microscopically there is no evidence of capsular invasion. Rarely, as noted by Jordan and co-workers (1981), hemorrhagic infarction of a parathyroid adenoma can cause rupture of the capsule and massive extracapsular hemorrhage. Numerous researchers, including Capps (1934), Stocks and Hartley (1986), and Berry (1974), Santos (1975), Sarfati (1985), Simic (1989), and Nakajima (2002) and their associates, have reported the occurrence of this complication. In two cases, this occurred in patients with mediastinal adenomas, resulting in chest pain and hypotension in one and neck swelling, dyspnea, and chest ecchymosis in the other. Three additional patients with spontaneous rupture of cervical adenomas were initially diagnosed as having dissecting aortic aneurysms. The triad of acute neck swelling, hypercalcemia, and ecchymosis of the neck or chest is strongly suggestive of this entity. Chest pain is also likely when the adenoma is located in the mediastinum (see Chapter 168).

Parathyroid Carcinoma

Parathyroid carcinoma is exceedingly rare. When parathyroid malignancy in the mediastinum occurs, Cohn and Silen (1982) and Dubost and colleagues (1984) report that, as a rule, it represents metastatic spread from a primary tumor in the neck. However, an example of a parathyroid carcinoma arising in an ectopic mediastinal parathyroid gland in the superior portion of the visceral compartment has been reported by Lee and Hutcheson (1974). Pezzullo and co-workers (2003) recently reported a large parathyroid carcinoma that mimicked a large substernal goiter on physical and radiologic examination. The histologic diagnosis is difficult, and the evidence of invasion is the best criterion.

TREATMENT

Mediastinal parathyroid tumors that cannot be excised by cervical thymectomy have been traditionally approached by a median sternotomy or thoracotomy. Minimally invasive techniques such as thoracoscopic and mediastinoscopic resections of mediastinal parathyroid adenomas have been reported with increasing frequency. The first thoracoscopic parathyroidectomy was performed in 1992 by Proye and colleagues in Lille, France, and reported by Prinz and colleagues (1994). Thoracoscopic resection has had an increasing role in the treatment of parathyroid adenomas as our localization and operative techniques continue to advance. For example, thoracoscopy has been used successfully to remove ectopic hyperactive parathyroid adenomas located in the mediastinum by Medrano (2000), Furrer (1996), and Smythe (1995) and their colleagues, among others. In some cases the lesion may be small and as such it may be difficult to identify it from the surrounding tissues at thoracoscopy. In such a situation, Ott and co-workers (2001) have used the preoperative injection of radioactive 99mTc sestamibi (in a patient whose lesion had been shown to take up the material during a diagnostic scan) to locate the small adenoma with a handheld gamma counter during the thoracoscopic procedure.

P.2819

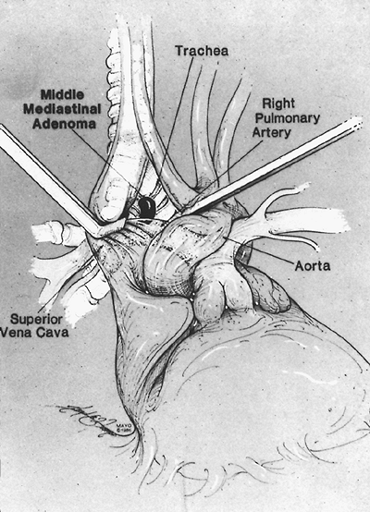

To perform a median sternotomy, we execute an initial sternal split to the third interspace level, because many tumors can be exposed through a limited sternotomy. If the tumor has been localized to a deeper level or is not found after an initial exploration, the sternotomy may be extended caudally to allow greater exposure. The entire thymus may be removed and the great vessels dissected. If the tumor has still not been identified, the pericardium is opened and the great vessels of the middle mediastinum are explored. Although the rare tumor in the region of the pulmonary artery on the right side may be difficult to locate, it is possible to do so through a median sternotomy, as pointed out by Curly and associates (1988), if the great vessels are adequately mobilized and gently retracted (Fig. 193-10). Boushey and Todd (2001) reported that the superior transpericardial approach to these middle mediastinal parathyroid adenomas is superior to that of a posterolateral thoracotomy. If a tumor has been localized in this region by imaging and the patient has had a previous sternotomy, Cheung and colleagues (1989) suggested that an anterior left thoracotomy may be used as an alternative. We have also infrequently used an inframammary left thoracotomy incision in several young women whose tumors were localized before any mediastinal exploration. This was done in deference to their desire to avoid any possible unsightly midline scar.

|

Fig. 193-10. Schematic drawing of operative exposure of a parathyroid adenoma in the visceral (middle) compartment of the mediastinum via a median sternotomy and retraction of the great vessels after ligation and division of the left innominate vein. A transpericardial approach would also be satisfactory. From Curley IR, et al: The challenge of the middle mediastinal parathyroid. World J Surg 12:818, 1988. With permission. |

In 38 patients who underwent a median sternotomy for parathyroid adenoma resection, Russell and colleagues (1981) reported a 29% morbidity. The primary complications consisted of pleural effusions (10.5%), pneumonitis (7.9%), and wound complications such as hematoma or sternal dehiscence (7.8%).

Candidates for thoracoscopic resection are those in whom the mediastinal parathyroid adenoma has been precisely located. Thoracoscopy is not advocated for an exploratory operation. The operation requires a double-lumen endotracheal tube and positioning of the patient laterally. The procedure, as described by Smythe and colleagues (1995), requires two incisions made for port sites in the fourth intercostal space, one at the anterior axillary line and one at the posterior axillary line. These port sites are used for resection instruments. A third incision is made in the seventh intercostal space at the midaxillary line. This third port site is for the fiberoptic camera and for placement of a 28F thoracostomy tube at the completion of the resection. The advantages of thoracoscopic removal over a sternotomy are decreased patient discomfort, decreased hospital stay, and decreased morbidity. Tovar (1999, 2001) has reported a minimally invasive thoracoscopic route via a small cervical collar incision and Wei and colleagues (1995) have described a subxiphoid laparoscopic approach for removal of mediastinal parathyroid lesions after preoperative localization by a 99mTc sestamibi radionuclide scan.

The advantages of the aforementioned surgical procedures over angiographic embolization procedures are that it is more successful in curing hyperparathyroidism, there is tissue for histopathologic evaluation, and it allows for preservation of parathyroid tissue for autotransplantation or cryopreservation.

With increasing experience, it is evident that some patients with mediastinal adenomas can be successfully treated by intraarterial hypertonic contrast material and embolization. This procedure should be carefully considered in selected poor-risk patients prior to referral to a skilled angiographer.*

REFERENCES

Batsakis C, et al: Giant mediastinal parathyroid adenoma in a woman with hypercalcemia. Clin Nucl Med 26:950, 2001.

Bauer W, Federman D: Hyperparathyroidism epitomized: the case of Capt. Charles F. Martell. Metabolism 11:21, 1962.

P.2820

Berry BE, et al: Mediastinal hemorrhage from parathyroid adenoma simulating dissecting aneurysm. Arch Surg 108:740, 1974.

Boushey RP, Todd TRJ: Middle mediastinal parathyroid: diagnosis and surgical approach. Ann Thorac Surg 71:699, 2001.

Calandra DB, et al: Parathyroid cysts: a report of eleven cases including two associated with hyperparathyroid crisis. Surgery 94;887, 1983.

Capps RB: Multiple parathyroid tumors with massive mediastinal and subcutaneous hemorrhage. Am J Med Sci 188:800, 1934.

Cheung P, Borgstrom A, Thompson NW: Strategy in reoperative surgery for hyperparathyroidism. Arch Surg 124:676, 1989.

Cohn KH, Silen WS: Lessons of parathyroid reoperations. Am J Surg 144:511, 1982.

Curly I, et al: The challenge of the middle mediastinal parathyroid. World J Surg 12:818, 1988.

Dieter RA Jr, O'Brien T, Carpenter R: Giant mediastinal parathyroid adenoma with hypercalcemia. Int Surg 87:217, 2002.

Doherty GM, et al: Results of a multidisciplinary strategy for management of mediastinal parathyroid adenoma as a cause of persistent primary hyperparathyroidism. Ann Surg 215:101, 1992.

Doppman JL, et al: Parathyroid adenomas in the aortopulmonary window. Radiology 201:456, 1996.

Dubost C, Bouteloup P-Y: Explorations mediastinales par sternotomie dans la chirurgie de l'hyperparathyroidie. J Chir (Paris) 125:631, 1988.

Dubost C, et al: Successful resection of intrathoracic metastases from two patients with parathyroid carcinoma. World J Surg 8:547, 1984.

Edis AJ, Grant CS, Egdahl RH: Manual of Endocrine Surgery. 2nd Ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1984, pp. 61 65.

Furrer M, Leutenegger AF, Ruedi T: Thoracoscopic resection of an ectopic giant parathyroid adenoma: indication, technique, and three years follow-up. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 44:208, 1996.

Guvendik L, et al: Management of a mediastinal cyst causing hyperparathyroidism and tracheal obstruction. Ann Thorac Surg 55:167, 1993.

Hattori Y, et al: Nonfunctioning parathyroid cyst in the mediastinum: report of a case. J Jpn Assoc Chest Surg 12:543, 1998.

Jordan FT, Harness JK, Thompson NW: Spontaneous cervical hematoma: a rare manifestation of parathyroid adenoma. Surgery 89:697, 1981.

Lee YT, Hutcheson JK: Mediastinal parathyroid carcinoma detected on routine chest films. Chest 65:354, 1974.

Levin KE, et al: Localization studies in patients with persistent or recurrent hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 103:917, 1987.

Linos DA, Schoretsanitis G, Carvounis C: Parathyroid cysts of the neck and mediastinum. Case report. Acta Chir Scand 155:211, 1989.

McHenry C, et al: Resection of parathyroid tumor in the aorticopulmonary window without prior neck exploration. Surgery 104:1090, 1988.

Medrano C, et al: Thoracoscopic resection for ectopic parathyroid glands. Ann Thorac Surg 69:221, 2000.

Nakajima J, et al: Parathyroid adenoma manifested by mediastinal hemorrhage: report of a case. Surg Today 32:809, 2002.

Norton JA, Schneider PD, Brennan MF: Median sternotomy in reoperations for primary hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg 9:807, 1985.

Ott MC, Malthaner RA, Reid R: Intraoperative radioguided thoracoscopic removal of ectopic parathyroid adenoma. Ann Thorac Surg 72:1758, 2001.

Pezzullo L, et al: Cervico-mediastinal carcinoma of the parathyroid: report of a case. Tumori 89:280, 2003.

Prinz RA, et al: Thoracoscopic excision of enlarged mediastinal parathyroid glands. Surgery 116:999, 1994.

Proye C, et al: Adenome parathyroidien mediastinale moyen de la fenetre aorto-pulmonaire. Chirurgie 114:166, 1988.

Rothmund M, et al: Diagnosis and surgical treatment of mediastinal parathyroid tumors. Ann Surg 183:139, 1976.

Rubello D, et al: An ectopic mediastinal parathyroid adenoma accurately located by a single-day imaging protocol of Tc-99m pertechnetate-MIBI subtraction scintigraphy and MIBI-SPECT-computed tomographic image fusion. Clin Nucl Med 27:186, 2002.

Russell CF, et al: Mediastinal parathyroid tumors. Experience with 38 tumors requiring mediastinotomy for removal. Ann Surg 193:805, 1981.

Santos GH, Tseng CL, Frater RW: Ruptured intrathoracic parathyroid adenoma. Chest 68:844, 1975.

Sarfati E, et al: Un adenome parathyroidien de localization exceptionelle au mediastin moyen. J Chir (Paris) 122:515, 1985.

Sarfati E, et al: Adenomes parathyroidien de sieges inhabituels, ectopiques ou non. J Chir (Paris) 124:24, 1987.

Shibata Y, et al: Mediastinal parathyroid cyst; a case resected under video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J Jpn Assoc Chest Surg 12:676, 1998.

Shields TW, Immerman SC: Mediastinal parathyroid cysts revisited. Ann Thorac Surg 67:581, 1999.

Simic KJ, et al: Massive extracapsular hemorrhage from a parathyroid cyst. Arch Surg 124:1347, 1989.

Smythe WR, et al: Thoracoscopic removal of mediastinal parathyroid adenoma. Ann Thorac Surg 59:236, 1995.

Stocks AE, Hartley LCJ: Hypercalcemia: the case of the missing adenoma. Med J Aust 145:92, 1986.

Thompson NW: Discussion on Edis A, et al: Results of reoperations for hyperparathyroidism with evaluation of preoperative localization studies. Surgery 84:384, 1978.

Thompson NW, Eckhauser F, Harness J: The anatomy of primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 92:814, 1982.

Tovar EA: Transcervical resection of an aorticopulmonary window parathyroid tumor. Surg Rounds 22:638, 1999.

Tovar EA: Minimally invasive resection of mediastinal parathyroid adenomas [Letter to the editor]. Ann Thorac Surg 71:402, 2001.

Wang CA, Gaz R, Moncure A: Mediastinal parathyroid exploration. A clinical and pathologic study of 47 cases. World J Surg 10:687, 1986.

Wei JP, et al: The subxiphoid laparoscopic approach for resection of mediastinal parathyroid adenoma after successful localization with TC-99m-sestamibi radionuclide scan. Surg Laparosc Endosc 5:402, 1995.

*This chapter was updated from the fifth edition by the Senior Editor with deep appreciation for the fundamental information and experience of the original authors.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203