Using the Tools of Persuasion

Now you are ready to think about persuasion strategies. When I teach groups of new leaders about influence in organizations, I often start with a simple thought experiment. You are sober, serious professional managers, I say. But suppose I wanted to get you to do something absurd and embarrassing, such as standing up, bouncing up and down on one foot with your thumbs in your ears singing ˜Row, Row, Row Your Boat at the top of your lungs. How might I persuade you to do that?

Shaping Perceptions of Choices

Two influence strategies usually emerge right away: bribery and threats. Both are examples of changing individual incentives to change behavior. Both alter how people perceive their alternatives when they are deciding whether to comply . This is the art of choice shaping .

Before bribes are offered or threats uttered, members of the group might perceive their alternatives ”status quo and change ”as shown in figure 8-2. Status quo means staying in one s seat, while change entails looking silly. Faced with this choice, most people would choose the status quo. People facing change in organizations often see their alternatives in the same way: Should I make uncomfortable changes or stick with the relatively comfortable status quo?

Figure 8-2: Choice Between Status Quo and Change

Now suppose I offer people money to do what I ask. The status quo option remains the same, but the attractiveness of the change option increases . Everyone has a price at which he or she would tolerate minor social discomfort because the payoff is sufficiently attractive.

The analogue in organizational change initiatives is: Find ways to compensate potential losers to make change more palatable. Of course, there are practical limits on your ability to do this; sometimes the price is simply too high. But it is always worth asking yourself whether you can offer trades or other forms of compensation (such as support for an initiative they care about) to win support.

Now suppose that, instead of offering compensation, I told the group to do as I said or I would get hired goons to break their legs. And suppose that my threat was credible: The doors were locked and the goons were visible, pipes and bars in hand. This influence strategy also alters the group s perceived alternatives. But rather than making the benefits of compliance more attractive, it makes noncompliance more costly. The perceived cost of looking silly remains the same, but the group no longer has the alternative of just sitting tight. The analogue in managing organizational change is: Find ways to eliminate the status quo as an alternative . If you can convince people that change is going to happen with or without them, for example, their choice is transformed as shown in figure 8-3.

Figure 8-3: Choice Between Participating or Having Change Happen Anyway

Framing Compelling Arguments

Eventually a participant in my demonstration says something like, All this talk about bribes and threats is distasteful. Why don t you just ask us to do it and see what happens? The answer is that it is by no means a certainty that people will comply without a persuasive argument or rationale. So I ask the group, Suppose I were simply to ask you to do this embarrassing thing. How could I increase the likelihood that you would comply? What rationale could I offer that might either reduce the perceived costs of action or increase the perceived costs of inaction?

One possible rationale I could offer is that doing what I ask would contribute materially to the educational objectives of the program. If the group believed me and found me credible (because of my expertise and authority as their instructor), my plea might move them. So it can help to marshal persuasive rationales and the data to back them up. A compelling argument for change can function in the same way.

Persuasive appeals can be based on logic and data, or on values and the emotions that values elicit, or on some combination thereof. Reason-based arguments have to directly address the pragmatic interests of the people you want to convince. Valuebased arguments aim to trigger emotional reflexes ”for example, by evoking patriotism to win support for sacrifices during wartime. Classic values invoked to convince others to embrace potentially painful change are summarized in table 8-1.

| Core Values | Within the Business Environment |

|---|---|

| Loyalty |

|

| Commitment and contribution |

|

| Individual worth and dignity |

|

| Integrity |

|

Setting Up Action-Forcing Events

How can you get people to take action at all? It is all too easy, even with the best intentions, to defer decisions, delay, and avoid committing scarce resources. When your success requires the coordinated action of many people, delay by a single individual can have a cascade effect, giving others an excuse not to proceed. You must therefore eliminate inaction as an option.

One approach is to set up action-forcing events ”events that induce people to make commitments or take actions. Those who make commitments should be locked into timetables with incremental implementation milestones. Meetings, review sessions, and deadlines can all sustain momentum: Regular meetings to review progress, and tough questioning of those who fail to reach agreed-on goals, increase the psychological pressure to follow through.

Be careful, though: Avoid pressing for closure until you are confident the balance of forces acting on key people is tipping your way. Otherwise, you could succeed in forcing them to take a stand, but inadvertently push them toward the opponent side of the ledger. Again, you need to rely on your conversations with the people involved and with your intelligence network to get a sense of where the situation stands.

Employing Entanglement

Reformulating incentives, framing arguments, and setting up action-forcing events are relatively static persuasion techniques: You figure out how people perceive their choices, and then you craft a mix of push and pull forces that alter those perceptions. Voil , you get the behavior you want.

But what if moving people from where they are (comfortable with the status quo) to where you want them to be (enthusiastically supporting change) is either impossible to achieve all at once or just too expensive for you? What do you do then?

You could adopt entanglement strategies that move people from A to B in a series of small steps rather than a single leap. To return to the example of inducing a group to do something embarrassing, I could start by asking them to stand up. Then I could ask them to stand on one foot, and so on.

One approach is to leverage small commitments into larger ones. If you are trying to launch a new initiative, begin by getting people to agree to participate in an initial organizing meeting. Then get them to commit to a subsequent meeting, then to doing a small piece of analysis, and so on. Entanglement works because each step creates a new psychological reference point for deciding whether to take the next small step. When possible, try to make each step irreversible, like a door that locks once it has been passed through. Getting people to make commitments in public, for example, creates a barrier to backsliding, as does getting commitments in writing.

A related technique to overcome resistance to change is a multistage approach to problem solving. Start by getting people to take part in some shared data collection, for example, on how the organization is performing relative to competition. Oversee this process carefully to be sure that they take a hard look at performance using external comparisons. The key at this stage is to get them to recognize that there is a problem or problems that must be dealt with.

When that task is done, shift the focus to gaining a shared definition of the the problem. What exactly is the problem? Push them hard to engage in root cause analysis, using process analysis tools if helpful. Then get them to work jointly on criteria for evaluating alternative courses of action. What would a good solution look like? How should we measure success?

Finally, use the resulting criteria to evaluate the alternatives. How do the various alternative approaches stack up? By the alternative-evaluation stage of this process, many people will accept outcomes they would have rejected at the outset.

Another entanglement strategy is to use behavior change to drive attitude change . This may sound backwards , but the attitude/behavior-change equation runs both ways. It is possible to alter people s attitudes (with a compelling argument or evocative vision) and thus to change their behavior. But attitude change, and its close organizational cousin cultural change, is difficult to achieve and to sustain.

It turns out, interestingly enough, that if you can change peoples behavior in desired ways, their attitudes will shift to support the new behavior. This occurs because people feel a strong need to preserve consistency between their behavior and their beliefs. The implication for persuasion is clear: It often makes sense to focus first on getting people to act in new ways, such as by changing measurement and incentive systems, rather than trying to change their attitudes. If you get them taking the right actions, the right attitudes will follow.

Sequencing to Build Momentum

As we have seen, people consistently look to others in their social networks for clues about right thinking, and defer to others with expertise or status on particular sets of issues. The resulting influence networks can be a formidable barrier to your efforts or a valuable asset, or both.

Let us return once more to the example of asking a group of people to do something embarrassing. Suppose that, in response to my request, a respected member of the group said, No way I m doing that. It is disrespectful and foolish. Almost certainly no one else in the group would do what I had asked. But suppose the same person jumped up, grabbed someone else and said, Let s do it! It ll be fun! The odds are that everyone else would eventually follow suit. In fact, the last to rise would feel social pressure to do so: What s the matter with you?

Now suppose I did an analysis of the group before this exercise and identified the most respected person. Suppose I met with that person before the exercise and enlisted his or her aid as a confederate to make some important points about group dynamics and social influence. The odds are good that this person would agree to do so ”and that others would follow.

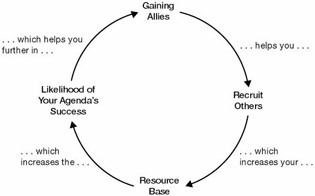

The fundamental insight is that you can leverage knowledge of influence networks into disproportionate influence on a group with what my colleague Jim Sebenius termed a sequencing strategy . [2] The order in which you approach potential allies and convincibles will have a decisive impact on your coalition -building efforts. Why? Once you gain a respected ally, you will typically find it easier to recruit others. As you recruit more allies, your resource base grows. With broader support, the likelihood increases that your agenda will succeed. That optimistic outlook makes it easier to recruit still more supporters.

If you approach the right people first, you can set in motion a virtuous cycle (figure 8-4). Therefore, you need to decide carefully who you will approach first, and how you will do it.

Figure 8-4: The Coalition-Building Cycle

Who should you approach first? Focus on the following:

-

People with whom you already have supportive relationships

-

Individuals whose interests are strongly compatible with yours

-

People who have the critical resources you need to make your agenda succeed

-

People with important connections who can recruit more supporters

[2] David Lax and Jim Sebenius coined this term . See David Lax and James Sebenius, Thinking Coalitionally, in Negotiation Analysis, ed. H. Peyton Young (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991), and James Sebenius, Sequencing to Build Coalitions: With Whom Should I Talk First? in Wise Choices: Decisions, Games, and Negotiations, ed. Richard J. Zeckhauser, Ralph L. Keeney, and James K. Sebenius (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996).

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 105