FINDINGS USING A CASE METHODOLOGY

Thus, using a case methodology to test the absence or presence of the factors listed in Figure 1, the results indicated in Table 2 emerged, based on data collected from 30 interviews, organizational documentation, participant observation and application demonstration.

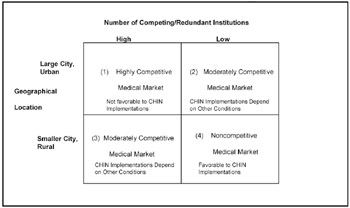

In-depth case data was collected from three voluntary CHIN implementations: the Wisconsin Health Information Network (WHIN), Regional Health Information Network of Northeast Ohio (RHINNO) and Northeast Ohio Health Network (NEOHN). The parallels among these CHINs make them appropriate for investigation. Each CHIN is located in the Midwest USA; they cover the range from big city to rural areas, and share common initial objectives i.e., sharing services among multiple health care players with the potential to increase profits. In addition, each of these CHINs is thought to have technology similarities with regard to data repositories, dedicated telecommunications media to enable interorganizational information sharing, and the IS expertise of a single vendor for technical, sales and marketing support. Thus, this sample of three CHINs is a starting point to uncover patterns in the CHIN/IOS implementation process which can later be studied in a broader sample. The results demonstrate that WHIN, NEOHN, and RHINNO represent CHINs that have met with different degrees of success. Both NEOHN and RHINNO have experienced cycles of interest, investment, and development, but no sustained operation as CHINs. On the other hand, WHIN serves as both an application (CHIN) vendor and an IOS venture electronically supporting its multiple health care participants. What differentiates these situations, and what implications can we draw from this for our model of IOS implementation? Perhaps the biggest difference in the study results between WHIN on the one hand and RHINNO and NEOHN on the other, is the apparent impact of Push/Pull Factors. While these factors showed little impact in the WHIN case, they had a largely negative impact for both RHINNO and NEOHN implementation. These factors are, no doubt, related to the environment. The nature of the market, geographical location, and infrastructure supporting CHIN implementation differentiates WHIN from the other two cases. The Wisconsin market is characterized by a fairly large group of relatively small, non-competing health care providers. CHIN implementation in this environment is not a zero-sum game. CHIN participants stand to lose little by engaging in cooperative information exchange processes. WHIN participants, unlike those in RHINNO and NEOHN, do not appear to endorse the idea that one organization's gain is another's loss. Further, CHIN participation becomes particularly appealing as smaller organizations recognize their inability to fund such massive infrastructures on their own, and larger, free-standing hospitals and payors realize their limited ability to finance the expenditures associated with implementation. WHIN and its participants are located in a smaller urban environment (unlike CHIN initiatives in New York, Chicago, and Cleveland), where health care players tend to be geographically dispersed. This, in part, engenders the need to electronically share information and may explain the lack of concern for competitive forces in the WHIN case. Figure 2 shows how the nature of the competitive environment might impact the desirability of shared IOS, including CHINs. In a large, urban market with many competing health care providers and/or payment plans, a highly competitive market develops (Box 1 of Figure 2). Institutions within this market are generally technologically sophisticated and often have their own, internal health care information systems and procedures in place to enable electronic data sharing. The nature of such markets could hinder CHIN implementations. Organizations in these competitive markets are likely to be unwilling to share information due to the perceived threat of competition. Consequently, there appears to be little justification for interorganizational cooperation or a voluntary CHIN in such markets. The Cleveland metropolitan market has these characteristics, and this may explain the failure of RHINNO to develop.

At the other extreme, small cities or rural areas with relatively few, geographically dispersed health care providers and payors present non-competitive markets (Box 4 of Figure 2). CHIN participation is most attractive in these cases, as organizations can engage in information sharing with little or no perceived threat of competition. The lack of service redundancy in the marketplace increases the likelihood that information sharing utilizing a shared infrastructure can add value. Markets in larger, less populous states are examples that fit this model. In such markets, push/pull factors like competition and economics as identified in the proposed CHIN implementation model (Figure 1) would likely favor implementation. Boxes 2 and 3 represent moderately competitive markets, which can develop both in large and small metropolitan regions. These settings fall somewhere between the extremes of those markets characterized by Box 1 or 4. They are likely to be smaller markets, or markets with less "density" of medical providers and payors. These are likely to be markets where the impact of competitive and economic factors on CHIN/IOS implementation is more difficult to predict. Markets like Milwaukee and Akron would seem to fall into this category. In Milwaukee, the lower degree of competition allowed WHIN to proceed successfully. In Akron, on the other hand, NEOHN was less successful, perhaps due to the proximity (and overlapping) of Cleveland (and RHINNO), a large, competitive (Box 1) market. These different market situations suggest the need for alternative models, both for CHIN functioning and for CHIN implementation. Health care players in highly competitive environments may participate in IOS educational, general organizational information, and clinical services. Similar to trade associations, such health care cooperatives could pool resources to gain power through political lobbying, engage in knowledge transfer particularly in specialized domains, and seek purchase discounts for needed technologies and services. Widespread sharing of patient information, however, will not occur easily in such markets, as powerful players develop proprietary systems to serve their own needs and maximize their individual market shares. In less competitive markets, the true potential of CHIN functionality for sharing data among multiple providers is more likely to be realized. As is evident from this study, the factors affecting CHIN implementation are likely to differ in different market situations. While Behavioral Factors seemed to play similar roles in each case, Push/Pull Factors and Shared System Topology (infrastructure) factors did not. The conditions for success depicted in the research model appear to be unattainable in certain environmental scenarios. This is particularly the case in environments characterized as a highly competitive. In these cases, the competitive forces, economic justification, political issues, and IOS enablers are most critical to determining implementation success they emerged as the go/no-go factors in the research model. Thus, it appears that the market for cooperative CHINs may be limited.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 194