1 - Introduction to Diabetes

Authors: Unger, Jeff

Title: Diabetes Management in the Primary Care Setting, 1st Edition

Copyright 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > 1 - Introduction to Diabetes

1

Introduction to Diabetes

I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel .

Maya Angelou, American poet, 1928

Take Home Points

Primary care physicians (PCPs) manage 90% of the patients with diabetes in the United States.

PCPs, on average, receive 4 hours of training related to diabetes while in medical school.

Twenty percent of patients seen in the primary care setting have diabetes.

PCPs should be adept at screening high-risk patients for diabetes. Early detection of the disease may reduce the risk of developing long-term diabetes-related complications.

Diabetes management in the primary care setting may be enhanced when physicians have access to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) standards of care, involve patients in their own care, partner with staff members and pharmaceutical companies to provide basic diabetes education in the office setting, and adapt the use of structured interview forms for data management.

Diabetes is exemplary of a chronic disease state, which offers an opportunity for PCPs to have a central role in managing and coordinating patient care.

Primary Care Physicians Should Provide the Cornerstone for Diabetes Care

Management of the patient with diabetes mellitus a chronic, disabling illness epitomizes the spirit of primary care medicine. Although specialists are often asked to evaluate and treat patients who have advanced complications or require complex treatment regimens, 90% of patients with diabetes can successfully be managed in a primary care setting.1,2 PCPs can screen high-risk

P.2

patients for diabetes, initiate treatment to reduce hyperglycemia, monitor and fine-tune pharmacologic therapies, as well as detect and manage microvascular and macrovascular complications. Family physicians also provide a portal for important life-altering information to their patients, such as access to certified diabetes educators (CDEs) and registered dieticians (RDs).

We are our patients' first line of defense for ensuring that their pregnancies have favorable outcomes, when we begin to discuss preconception planning with adolescents with diabetes. Armed with the knowledge that eating disorders are frequently encountered in adolescent patients with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) (see Chapter 8), we are able to elicit a history of the danger signs that are suggestive of this dangerous behavior pattern. Athletes seek our advice on how to manage their medication therapy when they are training for a marathon or seeking to join the high school football team.

Because PCPs monitor every aspect of their patient's metabolic history, we should not hesitate to share this information openly with other specialists. Imagine the appreciation an ophthalmologist would likely show if a patient arrived at his or her office complete with an updated medical history, A1C level, and lipid panel. Most specialists are forced to provide patient care without having access to this information, which may delay the integration of certain therapies into the patient's treatment regimen. For example, how could a nephrologist offer any advice to a patient who says only, My doctor sent me to you because he thinks my kidneys are failing. But honestly, I feel just fine! Where is the patient's glomerular filtration rate (GFR), blood count, A1C level, or tests for urinary albumin excretion? What medications is the patient taking? Is there a family history of chronic kidney disease? Does the patient have hypertension or hyperlipidemia? Communication with a specialist would be critical in these situations.

PCPs have a unique opportunity to evaluate, predict, and prevent many of the devastating long-term complications associated with diabetes. For example, simply identifying patients at high risk for diabetes developing based on their family history, ethnicity, history of gestational diabetes, or body-fat distribution should warrant the introduction of lifestyle and behavioral interventions that could delay or prevent the onset of diabetes (Table 1-1). Early and aggressive management designed to normalize hyperglycemia early in the course of the disease can improve outcomes.3,4,5

P.3

Case 1

Norma, age 32, has made this appointment for her annual physical. She is in excellent health and has no complaints. The doctor does note, however, that Norma has gained 4 pounds since her last visit 1 year ago.

Norma says: OK, I stopped exercising 4 months ago. I got too busy at work And you know with the kids getting back to school and their music lessons, I barely have any free time. But hey, I'm always chasing after them. Does that count as exercise?

Doctor: Norma, I see from your past medical records that you had gestational diabetes with your last pregnancy. How long ago was that, and how much did your baby weigh when he was born?

Norma: Eight years ago, the doctors said I had borderline diabetes, but 6 weeks after John was born, they tested me, and I was back to normal. Oh, John weighed 9 pounds. I remember that because they had to do a C-section, and the nurse in the delivery room said he was going to grow up to be a linebacker on the Raiders some day!

Doctor: Norma, the nurse did a fasting blood glucose level on you today, which was 226 mg per dL. That's a bit high. You may have diabetes, which is very common in patients like you who have a history of gestational diabetes. We are going to have to run some additional tests on you to determine if we need to start some medication to control your high blood sugars. We are also going to show you how to monitor your own blood sugar levels at home, fasting and at bedtime on Monday, Wednesday, and Sunday each week until I see you back in a month.

Norma: Oh no, do you think I have to go on the needle?

Doctor: Norma, there is a strong possibility that may be necessary in the future, depending on how well your blood sugars respond to our treatment plan. Remember, we will need to help you lose 7 pounds in the next year and show you what type of exercise program might be beneficial in controlling your hyperglycemia. We have treatment targets, Norma. If we can't get you to target with one therapy, we'll find one that will. We do not treat patients to failure here!

Norma: Thanks, Doctor.

Doctor: Norma, regarding John, because he weighed more than 9 lb at birth and you had gestational diabetes, he may be at risk for diabetes developing as well. Let me evaluate him next time you come in. If he is overweight for his age, I can suggest some dietary and exercise programs that could limit his weight gain and slow his progression toward diabetes. This is really important, because if we miss this opportunity to identify and treat high-risk patients like John, premature heart disease could develop.

Norma: I appreciate that, too, Doctor. John is really struggling in school right now. Lots of kids are teasing him about his weight. I've been concerned about this as well, but I can't get him off the computer long enough to talk to him about any health issues!

Table 1-1 Patients at High Risk for Developing Diabetes | ||

|---|---|---|

|

P.4

Encouraging behavioral changes requires our time and expertise. Although physicians argue that compensation for time spent with the patient may be minimal at best, we should not abandon these efforts based solely on financial incentives. As physicians, our ultimate responsibilities are to prevent illness and, in the case of diabetes, to offer comprehensive and aggressive treatment at the earliest stages of the disease.

Few of us could argue that in our modern era of polypharmaceutical intervention, patients are dying, not as the direct result of diabetes, but from the effects of the devastating complications related to their complex metabolic disorders. Despite our armamentarium of newer insulin analogues, novel insulin-delivery systems, incretin mimetics, thiazolidinediones, combination oral agents, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor agents (ARBs), and beta blockers, 70% of our patients with diabetes still die of heart disease.6 Numerous landmark evidence-based studies have proven the importance of intensively managing patients with all forms of diabetes. Yet, who among us is recommending, prescribing, and counseling our patients regarding these life-saving and life-altering interventions? In a move that is insulting and demeaning to our specialty, some insurers are refusing to allow PCPs to prescribe medications such as exenatide or pramlintide to our patients without their first being evaluated by an endocrinologist.

Let us take a closer look at this one point. Some insurance companies are preventing our patients from receiving timely and effective therapies as prescribed by licensed PCPs. In the belief that incretin mimetics and pulmonary insulin, for example, are specialty drugs, a patient must be referred to an endocrinologist prior to gaining access to these drugs. What the third party payors must understand is that not all endocrinologists are experts at diabetes management, preferring instead to subspecialize in treating thyroid

P.5

disorders, osteoporosis, or reproductive diseases. In some parts of the country, our patients are waiting 3 to 6 months before being evaluated by a diabetes specialist for a nonemergency appointment. As PCPs, we must be willing to stand up for our rights to ensure good comprehensive care for all of our patients, especially for those with chronic illnesses. As a group, we can have a profound effect on improving diabetes control in the United States.

Simply raising the A1C level from 6% to 10% will result in an 11% increase in overall costs for each patient with diabetes.7 If every PCP reduces the A1C levels by 2% in 100 of their patients, the financial savings realized per physician could be $150,000 over a 3-year period. The combined efforts of all 50,000 practicing members of the American Academy of Family Physicians at reducing the A1C levels of the diabetes patient population by 2% could reduce healthcare costs by $2.5 billion annually.

The cost of managing a patient with diabetes and coexisting coronary heart disease and hypertension over a 3-year period is 300% higher than the cost in those with diabetes alone ($46,000 vs. $14,000).7

Within 6 to 8 years of being diagnosed as having type 2 diabetes (T2DM), up to 80% of patients experience at least one episode of major depression (see Chapter 13). Depressed patients not only are at high risk for diabetes developing, but also have a higher incidence of coronary artery disease.8,9 Treatment costs over a 3-year period for depressed patients with diabetes average $32,000 versus $22,000 for those without coexisting depression.7 Patients with mental illness (such as major depression, bipolar depression, and schizophrenia) are unlikely to adhere successfully to their prescribed medical regimen unless their mental illness is stabilized.10 Rather than chastise these patients for their difficulty in controlling their diabetes, PCPs should take an active role in screening all patients with diabetes for mental illness and in treating this ubiquitous disorder when necessary.10 Screening for diabetes should also be performed on all patients with mental illness because of the higher prevalence of hyperglycemia in this population group.10

PCPs should welcome the challenge to become more involved in the management of their patients with diabetes. As gatekeepers, we have the responsibility to our patients, their families, and third-party payors to provide a foundation of comprehensive medical care for those who have chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemias. Although ideally, patients with diabetes should be managed by a group of knowledgeable clinicians and educators, the co-captains of this team should include the PCP and the patient. When consulted, the ophthalmologist will gladly perform a comprehensive dilated eye examination each year but is unlikely to provide the patient with any advice on improving lipid levels. The cardiologist would be delighted to detect a high-grade stenosis in the left coronary artery and suggest stent placements as soon as possible. Will the cardiologist also make certain that the patient is not having difficulty with balance or experiencing painful symptoms of peripheral neuropathy? Although we would not hesitate to refer a patient to a nephrologist to initiate dialysis on a patient

P.6

with end-stage renal disease, are we not better off identifying patients at risk for chronic kidney disease and providing them with a comprehensive treatment plan that may reduce their future dependence on dialysis?

As in a marriage made in heaven, we monitor our patients for years through the good times and the bad, through sickness and in health. We know our patients by their first names, their family histories, their gynecologic histories, their social histories, their types of employment or hobbies, the names of their medications, and their drug interactions. We are privy to some of their most intimate details. We are often the first physicians they consult regarding sexual dysfunction, infertility, depression, and marital discord. We are trained to inquire about physical, sexual, and verbal abuse in our chronic pain patients. Many of our patients feel most comfortable and confident in the PCP environment. For these reasons, the PCP's influence on our patients' diabetes outcomes should be substantial, and we should welcome these challenging patients into our practices with open arms. For so many of our patients, we have become their first and most important line of defense against microvascular and macrovascular disease.

Despite all our newest oral agents, faster and more predictably absorbed insulin analogues, new insulin-delivery systems (pens, pumps, inhalers), drug classes [incretin mimetics, amylin, and dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors], our patients with diabetes are still chronically hyperglycemic. Only one third of all patients with T2DM in the United States have been successfully treated to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommended glycosylated hemoglobin target of 7%.11 The rate-limiting step of diabetes management is fear of hypoglycemia. If hypoglycemia were not a concern, all patients with diabetes who were adherent to their treatment regimens could attain their prescribed A1C target. In the Diabetes Control and Complication Trial (DCCT), attempts to achieve near-normal glucose levels resulted in a 3.3-fold increase in the rate of severe hypoglycemia.12 To avoid hypoglycemia, patients must perform more frequent self-monitoring, anticipate situations during which they might be prone to develop hypoglycemia, and become knowledgeable about the recognition and management of low blood glucose values.13 Any physician who manages patients with diabetes should be prepared to discuss emergency management of hypoglycemia with their patients and families (see Fig. 6-8).

Does the A1C truly predict one's future risk for developing long-term complications? This is important to understand clinically, because a subset of patients in the DCCT maintained similar A1C values greater than 9% throughout the trial. However, the intensively treated patients had far less retinopathy and urinary albumin excretion than did the conventionally treated individuals. Although the DCCT demonstrated that intensively lowering the A1C from 9.1% to 7.2% can reduce the risk of microvascular complications by 60%,12 more recent analysis of the DCCT data suggests that wide glycemic excursions cause mitochondria to release superoxide molecules.14,15,16 These reactive oxygen species appear to incite the common complication pathways leading to microvascular and macrovascular disease (see Chapter 11). Thus, glycemic

P.7

variability within a given A1C range may be more predictive of one's future risk of developing complications. The intensively managed DCCT patients experienced less day-to-day glycemic variability when compared with patients taking insulin twice daily.

Glycemic variability may be minimized with the use of continuous glucose-sensing devices, which could be programmed to alarm when glucose levels fall to less than 70 mg per dL or rise to more than 240 mg per dL. Use of these devices in a recent clinical trial was shown to reduce by 21% the time spent in the hypoglycemic range (55 mg per dL) and by 23% the time spent exposed to hyperglycemia (>240 mg per dL), When compared with control subjects not using the sensors, 26% more time was spent within the glycemic target range (81 140 mg per dL). Although these sensors are available for clinical application, very few PCPs are knowledgeable about their existence or utility.

However, not every patient with diabetes will be given an insulin pump and sensor. Using frequent home blood glucose monitoring and comparing the standard deviations of patient meter downloads with the mean blood glucose readings during that reporting period will provide clinicians insight into how to improve glycemic variability by using a PC, meter software, and a cable attaching the meter to the PC. There is nothing fancy here, just simple and effective technology that is readily available to all healthcare providers (see Chapter 7). The use of hand-written glucose logs is so yesterday that some physicians will not even acknowledge their existence when they are turned in to the nurse. After all, a glucose log can be filled in with numbers that would satisfy anyone's mood on any given day. Let's see, do I want to make my doctor happy with my progress, or should I be confrontational today? Why not just confuse the doctor and write down some numbers that not even Einstein could interpret!

Managing Diabetes in the Primary Care Setting

The chronic progressive nature of diabetes that affects more than 20 million Americans17 and the devastating coexisting disease states that share its pathologic stage make diabetes a ubiquitous disease in primary care. Twenty percent of all patients seen by family physicians have diabetes.18 More than 90% of the patients with diabetes in the United States are managed by PCPs, the vast majority of whom have had less than 4 hours of diabetes-related education while in medical school.19,20,21 PCPs refer fewer than 10% of their diabetes patients to endocrinologists. Sixty percent of these referrals are for patients requiring insulin replacement therapy. More than half of these patients continue to receive their diabetes care with the endocrinologists.22

On average, a PCP will see 40 patients per day, which translates into an 8-minute visit per patient, many of whom have multiple complaints. The treatment and educational parameters outlined by the ADA and the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) (Table 1-2) can be addressed by physicians who become time managers, similar to an NFL quarterback trained in the 2-minute drill at the end of the game. Table 1-3 lists the common

P.8

discussion points related to diabetes management and the approximate time required to address each issue in a typical primary care setting.

Table 1-2 Diabetes Care Measures Used by the Provider Recognition Program of the American Diabetes Association/National Committee on Quality Assurancea | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Although managing diabetes may appear to be too challenging and time consuming on the surface, flow sheets, structured interview forms, and group education programs in the office setting allow physicians to provide comprehensive and motivational care to these patients. A summary of the 2006 standards of care for screening and treating patients with diabetes (Table 1-4) can be used as an excellent reference for anyone managing these complex patients.

Many different approaches may be helpful in implementing a more efficient means of monitoring and managing patients with diabetes in the office setting. The feasibility of each of the following suggestions will depend on the practice setting. Offices without a computerized reminder system may find pocket cards and flow sheets easy and effective to implement, whereas other practices may have the resources to implement a computerized tracking system or an electronic medical record with decision support. The initial step is to recognize the need to improve and to make a conscious effort to change.

The following suggestions may be helpful in streamlining one's approach to managing the expansive amount of data required to treat patients with diabetes successfully. The first step in treating patients with diabetes is to become as knowledgeable as possible about this complex metabolic disorder. Although a team approach is recommended for treating patients with diabetes, the team's thought leader should be the treating physician, who is ultimately responsible for the health and well-being of the patient.

P.9

P.10

Thought leaders should be well versed in the ADA standards of care, while promoting individualized care (Table 1-4).

Table 1-3 Time Required for In-office Patient Diabetes Management | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What works best for one patient may fail with another. Patients learn skills differently. Some of the most challenging patients to manage in the office setting are other healthcare professionals, who often must unlearn antiquated skills while reluctantly adapting behaviors that will offer them a great chance of successful outcomes. Knowledge forms the basis of successful diabetes management for both the treating physician and the patient.

Set standards for diabetes care. Recognition of the basic ADA guidelines regarding diabetes screening, glycemic control, hypertension, and lipid-treatment targets; use of aspirin; and frequency of eye, foot, and kidney evaluations are critical to basic diabetes care. These treatment standards are available online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/full/29/suppl_1/s4.

Involve the patients. Advise the patients to join the ADA. Online applications are available at: http://www.diabetes.org/membership/consumer.jsp. The more patients become involved in their chronic illness, the more likely they are to become active participants in their own long-term care. Encourage patients to become active in local chapters of the ADA. Physicians may even consider having monthly office-based diabetes support meetings. A general topic for these meetings can be posted in advance and announced in the local newspaper. Guest speakers such as RDs, CDEs, exercise physiologists, or other diabetes specialists can be invited to give presentations. Many of these group meetings are supported by grants available through local diabetes pharmaceutical sales representatives. An outstanding educational program featuring patients with diabetes who have achieved an A1C level of less than 7% is known as A1C Champions. Available through http://www.diabeteswatch.com/A1C/, these well-trained individuals will come to the medical office free

P.11

P.12

P.13

P.14

P.15

P.16

of charge and teach other patients how they too may become successful at reducing their A1C levels.Table 1-4 Standards of Care for Adults with Diabetes

Parameter Target Goals Screening for diabetes Initiate screening in all patients ages 45 and for diabetes older, then annually if screening test is negative for prediabetes or diabetes.

Screening should begin sooner in patients at high risk for diabetes developing (Table 1-1).

Community-based screening (i.e., health fairs are inappropriate venues for diabetes screening). Screening should be performed directly by a healthcare professional.

To screen for diabetes/prediabetes, either a fasting plasma glucose or a 2-h glucose challenge (using 75 g glucose) or both are appropriate.

Screening high-risk patients (Table 1-1) with a 2-h glucose challenge may detect more patients with abnormal glucose tolerance or diabetes than testing fasting plasma glucose.

See Figure 4-1 for impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and diabetes diagnostic criteria.A1C <7% (ADA)

<6.5% (AACE)a

Normal, 4% to 6%Preprandial glucose level 90 130 mg/dL (ADA)

<110 mg/dL (AACE)

Normal, 100 mg/dL2-Hour postprandial glucose level <180 mg/dL (ADA)

<140 mg/dL (AACE)

Normal, <140 mg/dLBlood pressure (no proteinuria) <130/80 mm Hg

Note: All patients with diabetes and hypertension should be treated with a regimen that includes either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB. If one class is not tolerated, the other should be substituted.

Before beginning treatment, patients with elevated blood pressure should have their blood pressure re-examined within 1 mo to confirm the presence of hypertension.Blood pressure (with proteinuria) <120/75 mm Hg Blood pressure (pregnancy with chronic hypertension) 110 129/65 79 mm Hg

Note: ACE inhibitors and ARBs are contraindicated during pregnancy. Antihypertensive drugs known to be effective and safe in pregnancy include methyldopa, labetalol, diltiazem, clonidine, and prazosin.Lipid screening Test annually, then more often if needed to achieve target goals. Lipid management goals for patients without overt coronary artery disease LDL-C <100 mg/dL

If older than 40 y, use statins to reduce LDL-C by 30% to 40% regardless of baseline LDL-C level.

If younger than 40 y, but at increased risk because of other CV risk factors, unable to achieve lipid goals via lifestyle modification, pharmacologic therapy is appropriate.Lipid-management goals for patients with overt coronary artery disease Use statin therapy to reduce baseline LDL-C by 30% to 40%. Attempt to lower LDL-C to the target of 70 mg/dL. Triglycerides HDL-C <150 mg/dL

<40 mg/dL (men); >50 mg/dL in women

Combination therapy with statins is often needed to achieve these goals.Antiplatelet therapy Use aspirin, 75 162 mg/day, for patients with diabetes + a history of CVA.

Use aspirin, 75 162 mg/d, for T1DM or T2DM patients older than 40 y + additional risk factors (+ family history of heart disease, hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, albuminuria).

Consider using aspirin in patients ages 30 40 in the presence of other cardiovascular risk factors.

Aspirin is not recommended for patients younger than 21 because of risk of Reye syndrome, those with aspirin sensitivity, those with history of a recent gastrointestinal bleed, or those with hepatic insufficiency.

Consider combination therapy of aspirin + clopidogrel for patients with severe and progressive coronary artery disease.Medical nutrition therapy Weight loss is suggested for all individuals with a BMI >25 kg/m2 who have diabetes or are at risk for developing T2DM.

Reduce caloric intake by 500 1000 kcal/day.

Carbohydrate intake should be 45% to 60% of total daily calories (low-carbohydrate diets are not advised).

Protein intake should be 15% 20% of total daily calories; lower (10% of total daily calories) in patients with nephropathy.

Fat intake should be 25% 35% of total daily calories, with <7% derived from saturated fat. Trans-fat intake should be minimized.

If adults with diabetes choose to use alcohol, daily intake should be limited to a moderate amount (1 drink per day or less for adult women and 2 drinks per day or less for adult men); 1 drink is defined as 12 oz beer, 5 oz wine, or 1.5 oz distilled spirits.

Routine nutritional supplements lack scientific support for efficacy or long-term safety and are not recommended.Physical activity 30 45 min of moderate aerobic activity 3 5 d/wk (a minimum of 150 min/wk).

More frequent and more intensive exercise programs are needed for successful weight reduction.

A graded exercise test with electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring should be seriously considered before undertaking aerobic physical activity with intensity exceeding the demands of everyday living (more intense than brisk walking) in previously sedentary diabetic individuals whose 10-y risk of a coronary event is likely to be 10%.

Patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy should avoid vigorous aerobic or resistance training.

Patients with peripheral neuropathy should participate preferentially in non weight-bearing activities such as swimming, bicycling, Pilates, yoga.

Patients with diabetic autonomic neuropathy are at risk for silent ischemia and should undergo a cardiac evaluation before initiating any strenuous exercise program.Screening for psychiatric disorders Screen for depression.

Screen for eating disorders.

Screen for cognitive impairment.Immunizations Influenza vaccine annually for all patients 6 mo or older

Provide at least one lifetime pneumococcal vaccine for adults with diabetes. A one-time revaccination is recommended for individuals older than 64 y previously immunized when they were younger than 65 y if the vaccine was administered more than 5 y ago. Other indications for repeated vaccination include nephrotic syndrome, chronic renal disease, and other immunocompromised states, such as after transplantation.Nicotine use All patients should be counseled against using nicotine. Coronary heart disease screening and treatment Assess cardiovascular risk in all patients annually. (These risk factors include dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, a family history of premature coronary disease, and the presence of micro- or macroalbuminuria.)

Candidates for a screening cardiac stress test include those with (a) a history of peripheral or carotid occlusive disease and (b) sedentary lifestyle, age older than 35 y, and plans to begin a vigorous exercise program. No data suggest that patients who start to increase their physical activity by walking or similar exercise increase their risk of a CVD event, and therefore, they are unlikely to need a stress test.

Patients with abnormal exercise ECG and patients unable to perform an exercise ECG require additional or alternative testing. Currently, stress nuclear perfusion and stress echocardiography are valuable next-level diagnostic procedures. A consultation with a cardiologist is recommended regarding further workup.Any patient with diabetes, older than 55, with any additional risk factor for coronary heart disease, should be given an ACE inhibitor, if not contraindicated, to reduce CV risk

Patients with history of myocardial infarction should be given a beta-blocker to reduce mortality.Screening for retinopathy Adults and adolescents with T1DM should have an initial dilated and comprehensive eye examination by an ophthalmologist within 3 5 y after the onset of diabetes.

Patients with T2DM should have an initial comprehensive eye examination performed by an ophthalmologist shortly after being diagnosed.

Annual follow-up eye examinations are recommended, although patients with normal and stable fundus examinations may be evaluated every 2 3 y.

Women who are planning pregnancy should undergo a comprehensive eye examination as well as during the first trimester of pregnancy, throughout pregnancy, and for 1 y postpartum.Screening for neuropathy Screen all patients initially for distal symmetric polyneuropathy by using simple clinical tests. Screening should be repeated annually.

Screening for autonomic neuropathy should be instituted at diagnosis of T2DM and 5 y after the diagnosis of T1DM.

Insensate feet should be visually inspected every 3 6 mo.

Consider referral to a podiatrist for special footwearbScreening and treatment of nephropathy Screen for microalbuminuria annually in patients with T1DM with diabetes duration 5 y or at onset of puberty.

Screen annually for microalbuminuria in all patients with T2DM at the time of diagnosis.

Screen for microalbuminuria during first trimester of pregnancy.

Serum creatinine should be measured at least annually for the estimation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in all adults with diabetes, regardless of the degree of urine albumin excretion.

ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be used for patients with CKD, except during pregnancy.

In patients with nephropathy, attempt to maximize glycemic control and limit glycemic variability.

Aggressively manage hypertension, hyperlipidemia, medical nutritional therapy, aspirin use, and anemia.

Specialty referral is suggested when the GFR is <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or if hypertension is resistant to treatment.

Nephrology referral is suggested when the GFR is <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.Foot examination Annual foot examination should include the following:

Visual inspection of the skin, looking for ulcers and calluses, palpation of peripheral pulses, sensorimotor evaluation, musculoskeletal evaluation, looking in particular for deformities, gait, and balance

Neurosensory evaluation

128-Hz tuning fork at base of the hallux

Monofilament testing

Deep tendon reflexes

Patients at risk for amputation include those who have lost all

protective sensation (insensate)

Altered biomechanics (foot deformity)

Evidence of increased pressure (erythema, hemorrhage under a callus)

Peripheral vascular disease

A history of ulcers or amputation

Severe nail pathology

Focus on patient education

Foot hygiene

Proper footwear

Foot trauma prevention/treatment

Visual inspection

Smoking and alcohol abuseACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor agent; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CV, cardiovascular; CVA, cardiovascular accident; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

aAACE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. (Source: AACE/ACE medical guidelines. Endocr Pract 2002;8[suppl 1]:40-82); ADA, American Diabetes Association.

bPatients who are insensate are unable to feel a 128-Hz tuning fork vibration at the base of the great toenail and/or are unable to perceive a monofilament anywhere on the foot. These patients have a 60% risk of an ulcer developing within 3 years and a higher risk if a foot deformity is present. Medicare will pay for 80% of one pair of custom footwear annually for insensate patients because custom footwear decreases ulceration rate from 60% to 20% over a 3-y period. (Source: National Diabetes Education Program. 2000. Available at: http://www.ndep.nih.gov/diabetes/pubs/Feet_HCGuide.pdf. Accessed 2/19/06.)

Notes:

- A1C is the primary target for glycemic control, not individual blood glucose levels.

- Glycemic targets should be individualized. High-risk patients, such as those with autonomic dysfunction, coronary heart disease, recent stroke, hypoglycemic unawareness, or elderly patients may require a higher A1C target.

- Children, adolescents, pregnant women, and women contemplating pregnancies have different A1C targets (see Chapter 8).

- Although achieving an A1C, 6% may reduce microvascular and macrovascular complications, patients may experience a higher likelihood of developing hypoglycemia and/or weight gain.

Data from American Diabetes Association. Position Statement: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2006. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:S4-S42Involve the staff. Physicians who manage patients with diabetes must engage their medical staff to become involved with patient care. Obviously not all PCPs have access to a CDE or an RD, much less to an insulin-pump trainer. Physicians can focus on interventional strategies that will improve long-term outcomes, while allowing their ancillary staff members to provide basic diabetes teaching skills, such as those shown in Table 1-5. Allow the pharmaceutical representatives to educate your nursing staff about their

P.17

diabetes products. Before long, the nursing assistants and the front-office personnel will feel comfortable handling the many complex gadgets and diabetes-treatment regimens.Table 1-5 Skills That May Be Used in the Primary Care Setting by a Trained Member of the Physician's Medical Staff

- Home blood glucose monitoring instruction. In addition, nursing assistants are excellent at assessing the patient's home monitoring techniques, especially if a large discrepancy is found between the A1C level and the level of control noted in the home blood glucose download study.

- Home blood glucose monitoring downloading

- Insertion and downloading of continuous glucose sensors

- Input data for global risk assessment such as UKPDS Risk Enginea and Diabetes PHDb

- Use of insulin pen injectors and inhaled insulin devices

- Teach integration of sensors and insulin pumps

- Teach basic concepts of carbohydrate counting to patients with good glycemic control

- Point-of-service A1C testing

- Provide instructions for initiation of insulin therapy, including timing, dosing, and location of injections. Preprandial and supplemental insulin dose strategies also can be discussed.

- Proper use of exenatide and pramlintide

- Provide instructions for proper foot care

- Discuss proper management and prevention strategies for hypoglycemia and sick-day regimens

- Authorize routine prescription refills

- Triage sick-patient phone calls

- Instruct in treat-to-target insulin protocols

- Provide screening tools for major depression and bipolar depression

- Arrange for specialty referrals

- Discuss prevention and management of hypoglycemia

- Assist patient with issues related to insulin pump training

aUKPDS, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study. This risk engine is available for downloading at http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/index.html?maindoc=/riskengine/download.html.

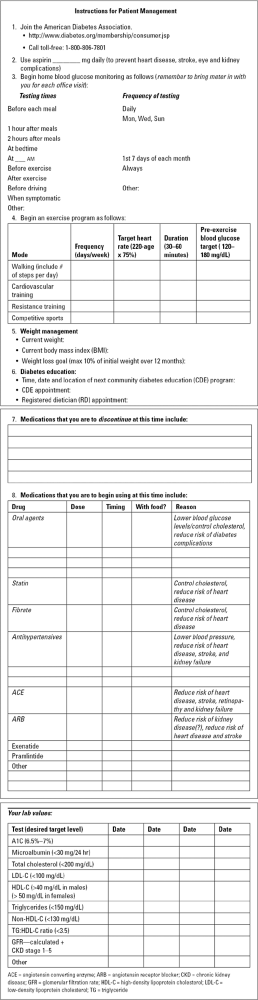

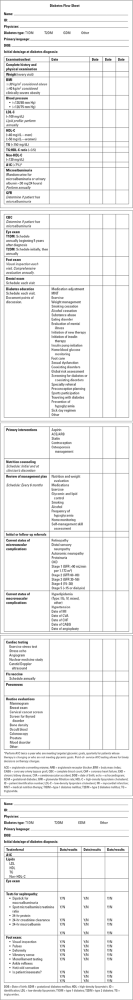

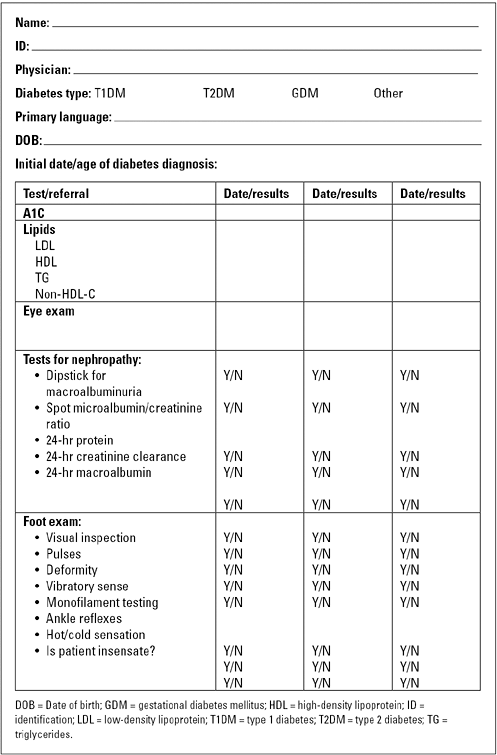

bDiabetes PHD, Personal Health Decisions (Table 1-3).Develop office tools for your patients. Although electronic medical records would be the ideal method of tracking and monitoring patients with diabetes, the majority of PCPs do not have access to these systems. The use of flow sheets and structured patient interviews is extremely helpful in organizing patient care. These forms may also be photocopied and provided to any specialist who is evaluating the patient, ensuring continuity of care. Figures 1-1,1-2,1-3,1-4 provide examples of flow sheets, a structured diabetes intake interview, and forms for patient encounters that may be of benefit in the primary care setting.

Provide nonbranded handouts to patients. Educational materials are appreciated by patients who may not fully comprehend the full extent of the illness. Patients may also leave the office confused as to the specifications of their individualized treatment plans. Consider writing down as much information as possible so the patient is able to review the instructions at a later date. Patients who are receiving insulin therapy should be given a copy of the prescribed treatment plan (see Fig. 5-12). The encounter form (Fig. 1-2) can be useful in providing patients with a comprehensive treatment plan as well as with goals to target future therapeutic interventions.

Opportunities to Intervene in Diabetes Management Abound in the Primary Care Setting

Diabetes provides PCPs with a unique opportunity to enhance the lives of patients by providing behavioral modification, preventive treatments, urgent therapies, and psychological support. In a patient with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), in all likelihood, T2DM eventually will develop. The PCP would suggest that these high-risk patients begin a daily exercise regimen, coupled with strategies to reduce their weight, in an attempt to delay their progression toward diabetes (see Case 1). Children born to mothers with GDM whose birth weight exceeded 9 pounds have a higher incidence of T2DM that develops during adolescence, which, in turn, would increase their risk of coronary artery disease during the second decade of life. Early intervention with patient education regarding lifestyle modification may be helpful in reducing the prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease in at-risk populations.

Preconception counseling can prevent microvascular complications and improve maternal/fetal outcomes. By initiating the discussion on preconception planning for all adolescent patients in the primary care setting, physicians are able to emphasize the benefits of attaining and maintaining targeted glycemic levels as soon as possible after the diagnosis of diabetes is made.

P.18

P.19

P.20

P.21

P.22

P.23

P.24

P.25

P.26

P.27

P.28

|

Figure 1-1 Comprehensive Structured Diabetes History Form. |

PCPs are trained in behavioral intervention strategies. By providing the proper guidance, therapeutic options, and encouragement to enhance successful outcomes, we can become a motivational force for our patients to replace harmful behaviors such as smoking and inactivity with healthful lifestyle interventions. Prescribing a basic exercise program, asking a patient to eat sensibly by using the ADA food pyramid (see Chapter 9), and providing patients with the tools necessary to perform home blood glucose monitoring (see Chapter 7) are neither time consuming nor counterproductive.

P.29

P.30

P.31

|

Figure 1-2 Patient Encounter Form. |

Our patients look to their PCP for guidance related to all aspects of their medical care, from managing influenza to diagnosing the cause of their chronic headaches. Patients realize that diabetes is a complicated disorder that lacks a cure. However, by guiding patients toward the lowest and safest attainable A1C level, we will allow them to live longer, more productive lives in the comfort of their own homes and away from the unfriendly confines of the intensive care unit (ICU).

PCPs should always be alert for patients at risk not only for having prediabetes, but those who might benefit substantially from early diagnosis and intervention of their abnormal metabolic profiles. PCPs are often consulted by patients who are concerned about acne, obesity, hirsutism, abnormal periods, and infertility. These patients may have polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (see Chapter 3), an endocrine disorder that predisposes the individual to diabetes and heart disease. Treating these patients with metformin or a thiazolidinedione (TZD) may allow them to become pregnant and improve their metabolic status.

Primary prevention of diabetes-related complications should be our first priority. Unfortunately, many of our patients are seen in our practices for the first time with poorly controlled diabetes of long duration. Our management must focus on secondary intervention strategies, as exemplified most often in patients with microvascular disease. Although we are unable

P.32

P.33

P.34

P.35

to reverse the structural damage to neurons, nephrons, or the retina, we can certainly provide patients with the tools necessary to slow the rate of disease progression and limit their physical disabilities. Our approach should always be focused on complication surveillance.

|

Figure 1-3 Diabetes Flow Sheet. |

Encourage patients to remove their shoes at each visit so that their feet can be inspected. Patients who are insensate should be given a monofilament to use on their own feet on a daily basis. Instead of telling a patient I want you to inspect your feet each night and let me know if you see anything

P.36

P.37

suspicous, ask the patient to use a monofilament on his feet each night before bedtime. In the case of patients who are insensate, you have my permission to tell them a little white fib. John, I'd like you to take this monofilament home with you. Beginning each night at bedtime, go ahead and touch your feet with the filament. Let me know when the feeling comes back into your feet (this is the white fib, by the way). As soon as you feel anything, let me know immediately. Oh, and if you happen to see any blisters, red spots, ulcers, or anything else that might concern you, I want to know about it right away! Go ahead and call my office. Thanks for helping us out here, John.

|

Figure 1-4 Data Collection Flow Sheet. |

In reality, the feeling in John's feet will never return. However, this patient is at high risk for a plantar ulcer or a Charcot foot syndrome. The use of the monofilament essentially forces John to inspect his feet each night. If he sees a suspicious area on the foot, he knows he has permission to contact his doctor. This proactive approach might save a limb. Having done this with my own patients, I have found even more success when I contact these individuals by phone 1 week after providing them with their monofilament. I ask them the following question: Hey John, this is your doctor. I'm just checking to see if you have felt any sensation in your feet since you started using that monofilament I gave you. Well, keep trying, because you never know when that tingling may return to your feet. Let me know if you see any funny stuff on your feet that concerns you. We'll see you next time around, and thanks for helping me keep you in such good shape!

Patients with chronic kidney disease should be advised to stop smoking. They should be given statins to lower their low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels to less than 100 mg per dL, take aspirin, limit their dietary intake of red meat, begin using an ACE or an ARB, reduce their blood pressure to less than 120/75, and be screened for anemia. Although appearing complicated, if not a bit overwhelming, these tasks are mandated by the ADA practice management guidelines23 and should be followed by all physicians caring for patients with diabetes.

PCPs may see one to two patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) each day, most of whom are at high risk for developing T2DM. Patients with T2DM and MDD share some common phenotypic characteristics: obesity, inactivity, cigarette smoking, and elevations in C-reactive protein. Not only do 80% of patients with T2DM have a history of MDD within 8 years of their initial diagnosis,24 but depressed diabetes patients also have a higher risk of coronary artery disease than do diabetic patients without mood disorders.8 Perhaps screening depressed patient for diabetes and patients with diabetes for depression should be considered.

Insulin resistance can have several implications. The insulin resistance syndrome refers to a cluster of metabolic abnormalities that may increase one's risk for developing cardiovascular disease. More than 52 million Americans are estimated to have metabolic syndrome25 (see Chapter 2), a disorder that can easily be recognized by observing the rolls of abdominal fat that extend beyond the belt line as the patient reluctantly stands on the

P.38

scale while making excuses about eating a donut on the way to the doctor's office.

The other type of insulin resistance involves the reluctance on behalf of patients and physicians to incorporate insulin therapy into the diabetes treatment plan. Patients perceive insulin as being the drug that caused Aunt Rose to go blind and lose her leg. Physicians believe that patients might walk away from their practice if they suggest using any type of injectable drug. Unfortunately, the intensification of diabetes therapy in the United States takes on average up to 10 years, during which time, persistent hyperglycemia causes irreversible glucose toxicity. We must overcome our fear of insulin by understanding when and how to use this drug appropriately in the office and hospital settings. Patients should be given insulin analogues whenever possible, rather than older insulin preparations such as NPH (neutral protamine Hagedorn) and regular. We now have at our disposal inhaled insulin, which may be advantageous to many of our patients requiring prandial insulin dosing. Patient-friendly insulin pen injectors and new-generation insulin pumps with real-time continuous sensor integration are now available. In the future, insulin pumps will become smaller, more user friendly, and easily adaptable to a primary care practice.

The marketing of exenatide and pramlintide provides novel therapies designed to reduce postprandial glycemia while limiting weight gain. Newer drugs that target glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) receptors and enzymes responsible for breaking down GLP-1 hormone (DPP-IV) will be available in the near future.

Within the past year, two new therapies have been approved for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathic pain. Historically, patients were prescribed drugs that, although they were effective, had multiple side effects and required frequent dosing titrations to reach a meaningful pain response. Duloxetine and pregabalin are both well tolerated and have been proven to improve global pain assessment significantly within 2 weeks of drug initiation. These drugs improve pain and patient function while appearing to work much more quickly than those that have been commonly used in the past for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. Drug therapy for male sexual dysfunction has all but eliminated the need for surgical intervention (see Chapter 11). The management of patients in the hospital setting is also becoming more intensive (see Chapter 10). Guidelines have been established for managing patients with diabetes in labor and delivery and in the ICU setting. Limiting hyperglycemia in the acute hospital setting has been shown to improve a number of long-term outcome parameters, including infections, myocardial infarction, and stroke recovery.

PCPs who manage diabetes during pregnancy must understand and anticipate the intricate glycemic changes that occur on a near-daily basis (see Chapter 8). One should not hesitate to become a partner with an obstetrician, perinatologist, endocrinologist, CDE, RD, or pediatrician who can assist in optimizing each patient's care.

P.39

Improving the Inertia toward Intensification of Therapy

The vast majority of patients with diabetes in the United States require intensification of their diabetes therapy. Koro et al.11 compared epidemiologic data from adult patients with T2DM from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2000. The mean A1C level increased 3% between these two population groups from an A1C level of 7.7% to 7.9%. The rate of glycemic control (defined as the percentage of patients with an A1C less than 7%) declined from 44.5% to 35.8% over a 12-year period. Thus, despite the current emphasis on early diagnosis and aggressive treatment, patients with T2DM are not attaining adequate glycemic control. Prolonged exposure to hyperglycemia will increase the likelihood of long-term complications developing and increase the costs of managing this chronic disease state.

We must be more aggressive in our approach to intensification of diabetes management. Our traditional approach to managing patients with T2DM includes prescribing a period of lifestyle intervention, followed by the introduction of a single oral agent. In time, as glycemic control deteriorates, a second oral agent is added, followed eventually by a third. Patients are informed that the diabetes is getting worse, and they must become more involved with their own care. Be careful with what you eat and exercise more often. When patients return several months later accompanied by another increase in the A1C levels, they may be labeled noncompliant. In reality, these patients are doing their best as their pancreatic beta cell function deteriorates. Eventually, and reluctantly, some of these patients are started on exogenous insulin therapy. Their improvement in A1C levels may be associated with uncomfortable weight gain and hypoglycemia. Frustration ensues on the part of the physician and the patient. Explain disease states to patients, as well as potential side effects of the commonly used medication regimens. If plan A is unsuccessful, move on to plan B. Simply giving a patient a pat on the back and providing a cursory statement such as, everything is going just fine, will not be well accepted by most individuals and accomplishes little in improving metabolic control. Do not be afraid to think outside the box. For example, a patient with severe insulin resistance using more than 150 units of insulin daily may do well with a basal insulin combined with U-500 insulin and exenatide. Consultation with specialists is encouraged for patients with complex management issues.

Patients at risk for developing T2DM should be screened according to the ADA guidelines.23 Lifestyle intervention should begin immediately for all high-risk individuals. Patients newly diagnosed with diabetes should be given combination drug therapy in addition to behavioral interventions. Failure to attain an A1C level of less than 7% should initiate a rapid progression to intensification of treatment. Strategies might include addition of another oral agent, an incretin mimetic, pramlintide, basal insulin plus oral agents, or inhaled insulin. Those patients who cannot achieve the targeted A1C levels

P.40

should be given an aggressive protocol using either a treat-to-target mixed insulin analogue protocol or a basal-bolus regimen. Improving the inertia toward diabetes intensification can reduce the time of the patient's exposure to hyperglycemia by 50%.

Table 1-6 Role of the Primary Care Physician in Diabetes Management | |

|---|---|

|

Aggressive management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes during the earliest stages of the disease process should provide patients with an opportunity to develop metabolic memory, reducing their chance of complications developing. PCPs can have a significant impact on the outcomes of diabetes patients. Table 1-6 suggests the role the PCP should take in managing diabetes.

Summary

As a chronic disease, diabetes offers an opportunity for PCPs to have a central role in managing and coordinating patient care. Diabetes has a broad spectrum of severity, with the majority of patients having a less severe and less intimidating form of the disease. Most patients with diabetes require pharmacologic regimens that are well established, widely used, and safe, allowing PCPs to provide care for many of their own patients and referring more complex cases to specialists. The coexisting disorders that accompany diabetes must be addressed by the PCP. Patients with chronic, poorly controlled hyperglycemia may have multiple complications that require the coordination and management skills of a shrewd practitioner. Finally, expertise in behavioral change and disease self-management is central to successful care of any chronic disease, especially diabetes. No one is better trained to promote patient adherence

P.41

and self-management to chronic disease states than PCPs. Whereas specialty training focuses on managing a single disease state or organ, PCPs understand the connection between the mind and the body. We know our patients better than anyone else. If we can make our patients feel good about themselves and their efforts in diabetes self-management, we should be able to help patients expand their lifetimes and live complication-free lives.

This book provides PCPs with the tools necessary to manage successfully the many medical challenges related to diabetes. Patients can achieve their targeted metabolic goals through a variety of lifestyle interventions and behavioral modifications. Simply admonishing a patient to lose weight, exercise, eat right, and check your sugars will most often result in a failed attempt at pleasing the medical provider. Patients will often incorporate a healthy lifestyle into their daily lives if they become partners in their own care and students of diabetes pathophysiology.

What an exciting era we have entered as we attempt to lead our patients with diabetes down a road less littered with weakened bodies riddled by complications. Before the discovery of insulin in 1922, patients died as a direct result of diabetes. In modern times, patients with diabetes are living on average 45 years longer than they did before insulin was available. The long-term consequences of chronic hyperglycemia exposure results in morbidity and mortality from eye, kidney, neurologic, and cardiovascular disease. Our landmark studies have taught us the importance of targeting the lowest and safest glycosylated hemoglobin level possible for each of our patients. Physicians know that intensification of diabetes therapy saves lives, eyes, kidneys, and hearts. We know the indisputable importance of enforcing lifestyle intervention, reducing blood pressure, improving lipids, reducing one's weight, and using aspirin therapy. So many evidence-based trials have been reported, yet how do we integrate these recommendations into our private practices?

Managing diabetes is certainly not an easy undertaking. However, we are embarking on a mission to prevent and delay complications that tend to develop and interfere with one's quality of life and productivity as many patients reach the prime of their lives. We owe our patients every opportunity to enjoy a long, meaningful, and enjoyable life, even in the shadow of diabetes. The following chapters should provide some practical and valuable clues on how these goals can be obtained in a primary care setting. Your patients will applaud your dedication to their cause, and so will I.

References

1. Unger J. Diabetes management in the new millenium (Editorial, Primary Care Edition). The Female Patient. 2001;6:10 11.

2. Hiss RG. Barriers to care in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: the Michigan experience. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:146 148.

3. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes four years after a trail of intensive therapy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:381 389.

P.42

4. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study Group. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2643 2653.

5. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. Intensive diabetes therapy and carotid intima-media thickness in type 1 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2294 2903.

6. Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229 234.

7. Gilmer TP, O'Connor PJ, Rush WA, et al. Predictors of health care costs in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:59 64.

8. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Russo J, et al. Cardiac risk factors in patients with diabetes mellitus and major depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1192 1199.

9. Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, et al. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2668 2672.

10. Unger J. Managing mental illness in patients with diabetes. Pract Diabetol. 2006; 25;44 53.

11. Koro CE, Bowlin SJ, Bourgeois N, Fedder DO. Glycemic control from 1988 to 2000 among U.S. adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a preliminary report. Diabetes Care. 2004;27: 17 20.

12. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977 986.

13. Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26: 1902 1912.

14. Hirsch IB, Brownlee M. Should minimal blood glucose variability become the gold standard of glycemic control? J Diabetes Complications. 2005;19:178 181.

15. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes. 1995;44:968 983.

16. Garg S, Zisser H, Schwartz S, et al. Improvement in glycemic excursions with a transcutaneous, real-time continuous glucose sensor: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:44 50.

17. CDC National Diabetes Fact Sheet United States 2005. Available on-line at http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/aag_ddt2005.pdf. Accessed 2/18/06.

18. Unger J. Type 2 diabetes patients need intensive management. Primary Care Network, Primary Issues. 2002;4:1 3.

19. Unger J. Targeting glycemic control in the primary care setting. The Female Patient. 2003;28:12-16

20. Unger J. Intensive management of type 1 diabetes. Emerg Med. 2001;33:30 42.

21. Unger J. Intensive management of type 2 diabetes. Emerg Med. 2001;33:28 43.

22. Endo and PCP needs survey: Lilly Pharmaceuticals. Data on File. 2002.

23. American Diabetes Association. Position Statement: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2006. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:S4-S42.

24. Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Clouse RE. Depression in adults with diabetes: results of 5-yr follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 1988;11:605 612.

25. Unger J. Diagnosing and managing insulin resistance syndrome. Emerg Med. 2004;36:36 43.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 19

- Chapter I e-Search: A Conceptual Framework of Online Consumer Behavior

- Chapter II Information Search on the Internet: A Causal Model

- Chapter VIII Personalization Systems and Their Deployment as Web Site Interface Design Decisions

- Chapter XI User Satisfaction with Web Portals: An Empirical Study

- Chapter XV Customer Trust in Online Commerce