MSF Risk Management Process

| As discussed at the beginning of this chapter, MSF Risk Management consists of two things: the MSF Risk Management Process and the discipline to use it efficiently, effectively, systematically, and repetitiously. This section bundles it all together into a process that enables proactive risk management, continuous risk assessment, and integration into decision making throughout a project or operational life cycle. A project needs just enough rigor to make sure that risks are continuously assessed, monitored, and actively managed until they are either resolved or turn into issues to be handled. Although the MSF Risk Management Process draws upon the well-known Software Engineering Institute (SEI) Continuous Risk Management process model[1],[2] for technical project risk, MSF seeks to interpret this model in view of Microsoft's extensive product development experience and the software development and deployment project experience derived from Microsoft Consulting Services (MCS) and Microsoft partners.

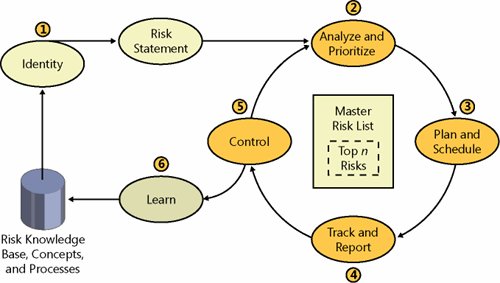

The MSF Risk Management Process consists of the following six steps, as depicted in Figure 5-1:

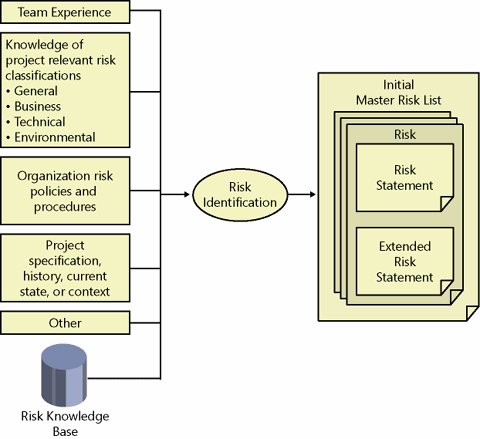

Figure 5-1. MSF Risk Management Process Note that these steps are logical steps and that they do not need to be followed in strict chronological order for any given risk. Teams often cycle iteratively through the identification analysis-planning steps as they develop experience on a project for a class of risks and only periodically visit a learning step for capturing knowledge for an enterprise. It should not be inferred from the diagram that all project risks pass through this sequence of steps in lockstep. Rather, MSF advocates that each project define during project planning when and how a risk management process will be initiated and under what circumstances transitions between the steps should occur for individual or groups of risks. For example, a project team might deem that all risks that have significant financial implications need to be reviewed by project sponsor(s) before being incorporated into a project schedule. Another example is when a cursory review of risks is performed to determine a tentative priority. After assessment of the impact on the schedule, more analysis might be required (i.e., bouncing risks between step 2 and step 3). The following sections explain each step of the MSF Risk Management Process. Step 1: Identify RisksRisk identification is the initial step in the MSF Risk Management Process. Risks must be identified and stated clearly and unequivocally so that a team comes to consensus and moves on to analysis and planning. During risk identification, a team focus should be deliberately expansive. Attention should be given to learning activity and directed toward seeking gaps in knowledge about a project and its environment that might adversely affect a project or limit its success. Figure 5-2 depicts graphically the inputs, outputs, and activities for a risk identification step. Figure 5-2. Risk identification GoalsThe goal of a risk identification step is for a team to identify project risks and, from them, produce a comprehensive, consensus list of these risks, covering all areas of a project in clear and unambiguous stated form. InputsThe inputs to a risk identification step are the available knowledge of general and project specific risk in relevant business, technical, organizational, and environmental areas. Additional considerations are the experience of a team; the current organizational approach toward risk in the forms of policies, guidelines, templates, and so forth; and information about a project as it is known at that time, including history and current state. A team can choose to draw upon other inputsanything that a team considers relevant to risk identification should be considered. At the start of a project, it is useful to employ group brainstorming, facilitated sessions, or even formal workshops to collect information on project team and stakeholder perceptions on risks and opportunities. Industry classification schemes such as the SEI Software risk taxonomy,[3] project checklists,[4] previous project summary reports, and other published industry sources and guides can also be helpful in assisting a team in identifying relevant project risks.

Risk Identification ActivitiesDuring risk identification, a team seeks to create an unambiguous statement or list articulating risks that they face. At the start of a project, it is easy to organize a workshop or brainstorming session to identify risks associated with a new situation. Unfortunately, many organizations regard this as a one-time activity, and never repeat the activity during a project or operations life cycle. MSF Risk Management emphasizes that risk identification should be undertaken at periodic intervals during a project. Risk identification might be schedule-driven (e.g., daily, weekly, or monthly), checkpoint-driven (associated with a planned checkpoint in a project plan), or event-triggered (forced by significant disruptive events in the business, technology, organizational, or environmental settings). Risk identification activities should be undertaken at intervals and with scope determined by each project team. For example, a team might complete a global risk identification session together at major checkpoints of a large development project, but might choose in addition to have individual feature teams or even individual developers repeat risk identification for their areas of responsibility at interim checkpoints or even on a weekly scheduled basis. During the initial risk identification step in a project, interaction between team members and stakeholders is very important because it is a powerful way to expose assumptions and differing viewpoints. For this reason, MSF advocates involvement of as wide a group of interests, skills, and backgrounds from a team as is possible during risk identification. Risk identification also can involve research by the team or involvement of subject matter experts to learn more about risks within a project domain. The two main areas of activity during an identification step are risk classification and risk statement formation. Risk ClassificationRisk classifications, sometimes called risk categories and risk taxonomies, serve multiple purposes for a project team. Risk classification provides a basis for standardized risk terminology needed for reporting and tracking. During risk identification, they stimulate thinking about risks arising within different areas of a project as well as providing a ready-made list of project areas to consider from a risk perspective that is derived from previous similar projects or industry experience. During brainstorming, risk classifications also ease complexities of working with large numbers of risks by providing a convenient way for grouping similar risks together. Finally, risk classifications are critical for establishing and maintaining working industry and enterprise risk knowledge bases because they provide a basis for indexing new contributions and searching and retrieving existing work. Table 5-1 illustrates high-level classifications for sources of project risk.

There are many taxonomies or classifications for general software development project risk. Well-known and frequently cited classifications that describe the sources of software development project risk include Barry Boehm,[5] Caper Jones,[6] and the SEI Software Risk Taxonomy.[7]

Lists of risk areas covering limited project areas in detail are also available. Schedule risk is a common area for project teams, and a comprehensive, highly detailed list for assisting software development project teams with risk identification around schedules has been compiled by Steve McConnell.[8]

Different kinds of projects (e.g., infrastructure or packaged application deployment), projects carried out with specialized technology domains (e.g., security, embedded systems, safety critical, EDI), vertical industries (e.g., health care and manufacturing), or solution-specific projects can carry well-known project risks unique to that area. Within the area of information security, risks concerning information theft, loss, or corruption as a result of deliberate acts or accidents are often referred to as threats.[9],[10] Projects in these areas will benefit from a review of alternative risk (threat) classifications or extensions to well-known general-purpose risk classifications to ensure breadth of thinking on the part of a project team during a risk identification step.

Other sources for project risk information include industry project risk databases such as the Software Engineering Information Repository (SEIR)[11] or internal enterprise risk knowledge bases.

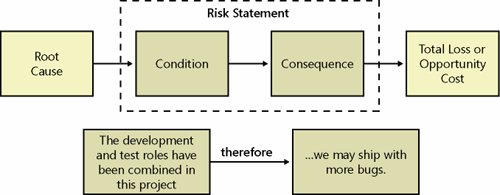

Risk StatementsA risk statement is a natural language expression of a causal relationship between a real, existing project state of affairs or attribute and a potential, unrealized second project event, state of affairs, or attribute. The first part of a risk statement is called the condition and provides a description of an existing project state of affairs or attribute that a team feels might result causally in a project loss or reduction in gain. The second part of a risk statement is called the consequence and describes an undesirable project attribute or state of affairs. The two parts of a statement are linked by a term or phrase such as "therefore" or "and as a result" that implies an uncertain (in other words, less than 100 percent sure) but causal relationship. This is depicted schematically along with an example in Figure 5-3. Figure 5-3. MSF risk statement The two-part formulation of risk statements has the advantage of coupling risk consequences with observable (and potentially controllable) risk conditions within a project early in a risk identification stage.[12],[13] Use of alternative approaches where a team focuses only on identification of risk conditions within a project during a risk identification stage usually requires that a team back up to recall a risk condition later on in a risk management process when they develop management strategies.

Although commonly done, it is not recommended that risk statements be written initially as "if-then" statements. Instead, it is recommended that risk statements be left loosely defined for later refinement during an analysis step. Similar to brainstorming where a goal is to get everything on the proverbial table without refinement or judgment, the goal of risk identification is to identify as many risks as possible, deferring what-if analysis for a Plan Track (discussed in Chapter 8, "MSF Plan Track: Planning a Solution"). During risk identification, it is not uncommon for a team to identify multiple consequences for the same condition. Sometimes a risk consequence identified in one area of a project can become a risk condition in another. These situations should be recorded by a team so that appropriate decisions are made during risk analysis and planning to take into account causal dependencies and interactions among risks.

When formulating a risk statement, a team should consider both the cause of the potential, unrealized less desirable outcome as well as the outcome itself. A risk statement includes the observed state of affairs (condition) within a project as well as the observable state of affairs that might occur (consequence). As part of a thorough risk analysis (a step that is often overlooked), team members should look for similarities and natural groupings of the conditions of project risk statements and backtrack up the causal chain for each condition, seeking a common underlying root cause.[14] It is also valuable to follow the causal chain downstream from a conditionconsequence pair in a risk statement to examine effects on an organization and environment outside a project to gain a better appreciation for the total losses or missed opportunities associated with a specific project condition.[15]

Depending on the relationships among risks, closing one risk might close a whole group of dependent risks and change an overall risk profile for a project. Documenting these relationships early during the risk identification stage provides useful information for guiding risk planning that is flexible, comprehensive, and that uses available project resources efficiently by addressing root or predecessor causes. Benefits of capturing such additional information at an identification step should be balanced against rapidly moving through the subsequent analysis and prioritization and then reexamining the dependencies and root causes for the most important risks during a planning and scheduling step. OutputsThe minimum output from risk identification activities is a clear, unambiguous set of risk statements faced by a team, recorded as a risk list. A risk list in tabular form, as exemplified in Table 5-2, is the main input for the next stage of the risk management processanalysis. The risk identification step frequently generates a large amount of other useful information, including the identification of root causes and downstream effects, affected parties, owner, and so forth.

Initial Master Risk ListA master risk list is the compilation of all risk assessment information at an individual project list level of detail. It is a living document that forms a basis for an ongoing risk management process and should be kept up-to-date throughout the cycle of risk analysis, planning, and monitoring. A master risk list is a fundamental document for supporting active or proactive risk management. It enables team decision making by providing a basis for the following activities:

An example of an initial master risk list resulting from an identification step is depicted in Table 5-2. Extended Risk StatementsWhen identifying individual project risk, it is beneficial to record additional information with a risk statement to provide context to assist others in better understanding a risk.[16],[17],[18] Although not part of a risk statement, this information coupled with a risk statement is often referred to as an extended risk statement or risk statement form. Note that given the potential verbose nature of this additional information, it is sometimes easier to retain it as a separate document from a master risk list. This information also helps classify risks (by project area or attribute)especially when using project risk information to build and use an enterprise risk knowledge base. Risk context information that some project teams might choose to record during risk identification to capture team intent includes the following:

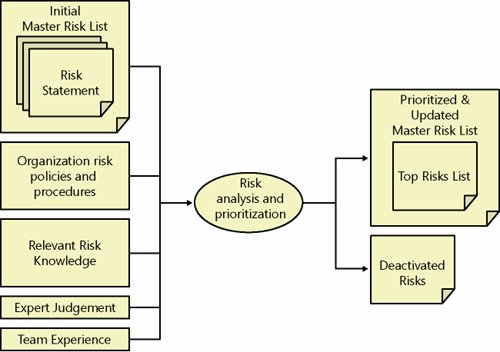

It is typical that this information might not be fully known during an identification step. This information can also be added during subsequent steps. Step 2: Analyze and Prioritize RisksRisk analysis and prioritization make up the second step in the MSF Risk Management Process. Risk analysis involves conversion of risk data into a form that facilitates decision making. Risk prioritization ensures that team members address the most important project risks first. Selecting the "right" risk analysis method or combination of methods depends on making the right trade-off decision between expending effort on risk analysis or making an incorrect or indefensible (to stakeholders) prioritization choice. Risk analysis should be undertaken to support prioritization that drives decision making and should never become analysis for the sake of analysis. The results from quantitative or semiquantitative approaches to risk prioritization should be evaluated within the context of business goals, opportunities, and sound management practices and should not be considered an automated form of decision making by itself. During this step, a team examines an initial list of risk items produced in the risk identification step and prioritizes it for action, within a master risk list. A team determines to which top risks they will commit resources for planning and executing a specific strategy. A team also identifies which risks, if any, are of such low priority for action, and not likely to increase in priority, that they can be dropped from a list. As a project moves toward completion and as project circumstances change, risk identification and risk analysis will be repeated and changes made to a master risk list. New risks might appear and old risks that no longer carry a sufficiently high priority might be removed or deactivated. The inputs and outputs to this step are depicted in Figure 5-4. Figure 5-4. Risk analysis and prioritization GoalThe goal of this step is to perform just enough analysis of each risk to be able to prioritize items on a risk list and determine which of these risks warrant commitment of resources for planningtypically for the highest priority risks.

InputsDuring the risk analysis and prioritization step, a team draws upon its own experience and information derived from other relevant sources regarding risk statements produced during risk identification. Relevant information to assist the transformation of an initial master risk list into a prioritized master risk list can be obtained from an organization's risk policies and guidelines, industry risk databases, simulations, analytic models, business unit managers, and domain experts, among others. Risk Analysis ActivitiesRisk analysis is the process of transforming estimates or data about specific project risks into a form that the team uses to make decisions around prioritization. Many qualitative and quantitative techniques to accomplishing prioritization of a risk list exist. One easy-to-use technique for risk analysis is to use consensus team estimates of two widely accepted components of risk: probability and impact. Risk ProbabilityRisk probability is a measure of the likelihood that the state of affairs described in the risk consequence portion of a risk statement will actually occur. Whatever measure is used to indicate priority, it must be clearly understood across the team and all stakeholders. Typically, a team will use ratings in numerical form or natural language expressions (e.g., high, medium, low). Which one used is often dictated by the way in which probability is determined. For instance, if probability is mathematically calculated, a numerical rating is often used. If communicating with stakeholders and users, natural language ratings are more intuitive and therefore are used. However, an obvious downside of using natural language ratings not based on numeric values is that level determinations are subjective and therefore prone to inconsistent leveling. This issue increases as the number of levels used increases. Probabilities are notoriously difficult for individuals to estimate and apply, although industry or enterprise risk databases can be helpful in providing known probability estimates based on samples of large numbers of projects. Most project teams, however, verbalize their experience, interpret industry reports, and provide a spectrum of natural language terms. If necessary, these terms are mapped back to numeric probability ranges. This can be as simple as mapping "low-medium-high" to discrete probability values (e.g., 17%, 50%, 84%) or as complex as mapping different natural language terms, such as "highly unlikely," "improbable," "likely," and "almost certainly." So, how many levels are recommended? A rule of thumb is to use the simplest means necessary to adequately represent the degree of precision needed. Table 5-3 demonstrates an example of a three-value division of risk likelihood expressed in probabilities. Table 5-4 demonstrates a seven-value division.

Note that the probability values used for calculation in the tables represent a midpoint of each range. With the aid of these mapping tables, an alternative method for quantifying probability is to map a probability range or natural language rating agreed upon by the team to a numeric score. No matter what technique is used for quantifying uncertainty, a team needs to agree on a consistent rating approach for risk probability that represents their consensus view regarding each risk. Also provided in the tables for each level of probability is a numeric score. This is just another way to represent a range of probability. Typically, the numeric score used for each probability range is a linear progression of values starting from 1. Risk ImpactRisk impact is an estimate of the severity of adverse effects, or the magnitude of a loss, or the potential opportunity cost should a risk be realized within a project. It should be a direct measure of the risk consequence as defined in a risk statement. Like probability, impact might be represented either in numerical terms or as natural language expressions. Unlike probability, more flexibility is afforded to define what is meant by "impact." For instance, impact might be represented in various terms, such as financial loss, schedule slippage, or market share. In addition to natural language ratings often used for probability, an additional level is used with impact (e.g., critical) to emphasize catastrophic impact to a project. As such, an artificially high score is assigned. This ensures that a risk with even low probability will rise to the top of a risk list and remain there if the impact is serious. A scoring approach for estimating impact often matches the complexity of how impact is determined (i.e., simple impact assessments lead to simple scoring). An impact score should reflect a team's and organization's values and policies. For instance, if impact is measured financially, a $10,000 monetary loss that is tolerable for one team or organization might be unacceptable for another. Hence, the former team might assign a low impact score whereas the latter team will likely score the impact higher. Table 5-5 is an example of natural language ratings for impact and their respective scores.

The following two sections provide a bit more insight on impact scoring. They discuss impact scoring based on a single attribute and on multiple attributes. Single-Attribute Impact ScoringThe simplest form of determining risk impact is to use only one attribute. Often, using only one attribute makes it easier and more intuitive to quantify the magnitude of loss or opportunity cost. It also helps when communicating to stakeholders and users to relate impact in their terms. For instance, financial impact can be agreed to represent long-term costs in operations and support, loss of market share, short-term costs in additional work, or opportunity cost. Once a team reaches agreement on what "impact" means, the same people need to agree on quantifying the magnitude of the impact. It is helpful to create translation tables relating specific units such as time or money into values that can be compared to subjective units used elsewhere in the analysis, as illustrated in Table 5-6. This approach provides a highly adaptable means for comparing the impacts of different risks across multiple projects and at an enterprise level.

Multiattribute Impact ScoringAt times, it is challenging to assess impact using only one attribute. Often, impact results from a confluence of factors. As such, a team might need to assess impact based on multiple attributes. Table 5-7 provides an example of determining impact based on multiple attributes.[19]

If possible, try to use attributes that are not too project specific because assessing risk at the program, portfolio, and/or enterprise level will be challenging. Risk Prioritization ActivitiesRisk prioritization is the process of ranking risks in order of their overall threat to an organization and, therefore, their priority for action. Because a goal of risk analysis is to prioritize risks and to drive decision making regarding commitment of project resources toward risk control, it should be noted that each project team should select a method for prioritizing risks that is appropriate to a project, a team, stakeholders, and risk management infrastructure (tools and processes). The simplest form of common quantitative means to prioritize risk is to sort them by a single calculated value, called risk exposure, derived by multiplying risk probability by risk impact. Like impact scoring, other more advanced means of prioritization are based on multiple attributes. Risk Exposure: Simple Prioritization ApproachRisk exposure measures the overall threat of a risk, combining information expressing the likelihood of actual loss (i.e., probability) with information expressing the magnitude of a potential loss (i.e., impact) into a single rating estimate. Risk exposure can be represented either in numerical terms or as natural language expressions. When nonnumeric scores are used to quantify probability and impact, it is sometimes convenient to create a matrix that considers the possible combinations of scores to determine a resultant exposure rating. For example, Table 5-8 is a common assignment of exposure given natural language expressions of probability and impact. In this arrangement, it is easy to classify risks as low, medium, high, and critical depending on their position within the diagonal bands of increasing score.

Multiattribute Prioritization ApproachIn addition to risk exposure, some projects can benefit from use of other attributes in determining risk priority. Commonly, weighted multiattribute techniques are used to factor in other components that a team wishes to consider in a ranking process such as required time frame, magnitude of potential opportunity gain, or reliability of probability estimates and physical or information asset valuation. An example of a weighted prioritization matrix that factors in not only probability and impact but critical time window and cost to implement an effective control is shown in Table 5-9, where ranking score is calculated using this formula: Ranking value = 0.5 (Probability x Impact) 0.2 (when needed) + 0.3 (Control cost x Probability control will work)

This method enables a team to factor in risk exposure and schedule criticality (when a risk control or mitigation plan must be completed to be effective), and to incorporate the cost and efficacy of the plan into the decision-making process. This general approach enables a team to rank risks in terms of the contribution toward any goals that they have set for a project and provides a foundation for evaluating risks both from the perspective of losses (impact) and opportunities (positive gains). Deactivating RisksRisks can be deactivated or classified as inactive so that a team concentrates on those risks that require active management. Classifying a risk as inactive means that the team has decided that it is not worth the effort needed to track that risk. A decision to deactivate a risk is made during risk analysis. Some risks are deactivated because their probability is effectively zero and likely to remain so, that is, they have extremely unlikely conditions. Other risks are deactivated because their impact is below a threshold where it is worth the effort of planning a mitigation or contingency strategy; it is simply more cost-effective to suffer the impact if a risk is realized. Note that it is not advisable to deactivate risks above this impact threshold even if their exposure is low, unless the team is confident that the probability (and hence the exposure) will remain low in all foreseeable circumstances. Also, note that deactivating a risk is not the same as resolving one; a deactivated risk might reappear under certain conditions and the team might choose to reclassify a risk as active and initiate risk management activities. OutputsRisk analysis provides a team with a means to prioritize a master risk list to guide the team in risk planning activities. Because a master risk list can include many risks, a team should focus only on the highest priority risks, collectively called the top risks list. Prioritized Master Risk ListA master risk list was introduced during the risk identification step. The analysis step enables a team and stakeholders to mutually agree on a means to prioritize risks in a master risk list. Table 5-10 is an example of a prioritized master risk list in tabular form using a two-factor (i.e., probability and impact) estimate approach.

Top Risks ListRisk analysis weighs the threat of each risk to help a team decide which risks merit action. Managing risks takes time and effort away from other activities, so it is important for a team to do only what is necessary to manage them. A simple but effective technique for monitoring risk is to list risks and establish a cut-off for ones that are considered high priority (i.e., top risks list). The top risks list is externally visible to all stakeholders and often is included in critical reporting documents, such as the vision/scope document, project plan, and project status reports. Typically, a team identifies a limited number of high-priority risks that must be managed (usually 10 or fewer for most projects) and allocates project resources to address them. If it becomes necessary to address more than the top 10 risks, the list should be segmented and the higher priority risks addressed before moving to less critical risks. After ranking risks, a team should focus on a risk management strategy and how to incorporate risk action plans into the overall plan. Additional Analysis MethodsSome teams might choose to perform additional levels of analysis to clarify their understanding of project risk. Alternate techniques performed by the team to provide additional clarification of project risk are discussed in standard project management and risk management textbooks.[20],[21] Techniques such as decision tree analysis, causal analysis, Pareto analysis, simulation, and sensitivity analysis have all been used to provide a richer quantitative understanding of project risk. These techniques provide good root cause analysis that can help identify issues not apparent by analyzing individual risks. The decision to use these techniques should be based on value that a team feels these tools bring in either driving prioritization or in clarifying the planning process to offset resource costs.

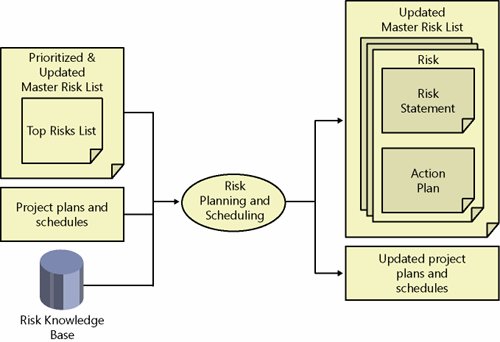

Step 3: Plan and Schedule to Manage RisksRisk planning and scheduling is the third step in the risk management process. Planning involves developing detailed strategies and actions for each of the top risks, prioritizing risk actions, and creating an integrated risk management plan. Scheduling involves the integration of the tasks required to implement risk action plans into a project schedule by assigning them to individuals and actively tracking their status. The inputs and outputs of this step are depicted schematically in Figure 5-5. Figure 5-5. Risk planning and scheduling GoalsThe goals of the risk planning and scheduling step are to develop detailed plans for addressing the top risks identified during risk analysis and to integrate these plans with project plans using standard project management processes to ensure that they are completed. InputsMSF advocates that risk planning be tightly integrated into the standard project planning processes and infrastructure. Inputs to the risk planning process include not only a master risk list and information from the risk management knowledge base, but also project plans and schedules. Risk Planning ActivitiesRisk planning is a process of trying to reduce risk exposure of the top risks and developing action plans for those that remain top risks. The first step in the process is to attempt to reduce exposure for each risk (i.e., reduce probability and/or impact). If not reduced sufficiently, action plans need to be formed to handle a risk should it be realized. Exposure ReductionConsistent with the proactive philosophy of MSF, it is better to mitigate a risk before it is realized. In support of this, a team should first seek to reduce risk exposure, starting with the top priority risks and working down in priority. The following are a few risk reduction approaches to consider:

Risk Action PlanningSo now that the risks have been identified, a team needs to do something about those pesky risksbut what? If exposure reduction activities have not yielded sufficient results, action plans need to be developed to deal with the potential realization of the risks deemed worthy of redress, typically the top risks. The first step in formulating an action plan is for the team to consider which of the following six approaches to handling risk best fit the needs of a project (explained further in subsequent sections). Based on which approach is selected, plan details need to be worked out. This includes planned adjustments in committed resources, schedule, and feature set, resulting in a set of risk action items specifying individual tasks to be completed by team members. A team should also understand how these tasks will be integrated into standard project plans and schedules, should it be necessary.

ResearchMuch of a risk that is present in projects is related to uncertainty surrounding incomplete information. Risks that are related to lack of knowledge can often be resolved or managed most effectively by learning more about a domain before proceeding. For example, a team might choose to pursue market research or conduct user focus groups to learn more about user baseline skills or willingness to use a given technology before completing a project plan. If the decision by a team is to perform research, a risk plan should include an appropriate research proposal, including hypotheses to be tested or questions to be answered, staffing, and any needed laboratory equipment. AcceptSome risks are such that it is simply not feasible to intervene with effective preventative or corrective measures, so a team elects to accept a risk to realize an opportunity. Acceptance is not a "do nothing" strategy, and a plan should include development of a documented rationale for why a team has elected to accept a risk and not develop mitigation or contingency plans. It is prudent to continue monitoring such risks through a project life cycle in the event that changes occur in probability, impact, or the ability to execute preventative or contingency measures related to this risk. These ongoing commitments to monitor or watch a risk should have appropriate resources committed and tracking metrics established within an overall project management process. AvoidOn occasion, a risk is identified that is easily controlled by changing the scope of a project in such a fashion as to eliminate the risk altogether (e.g., remove activities that have unacceptable risk). The risk plan should then include documentation of the rationale for a change, and the project plan should be updated and any needed design change or scope change processes initiated. TransferSometimes it is possible for a risk to be transferred so that it can be managed by another entity outside of a project. Examples where risk is transferred include these:

Risk transfer does not mean risk elimination. Rather, it means a reduction to an acceptable level of risk. In general, these risks still require proactive management and might even generate new risks. For instance, using an external consultant might transfer technical risks outside of the team, but can introduce risks in project management and budgetary areas. MitigationRisk mitigation involves actions and activities performed ahead of time either to prevent a risk from occurring altogether or to reduce the impact or consequences of its occurring to an acceptable level. For example, using redundant network connections to the Internet reduces the probability of losing access by eliminating a single point of failure. In cases where mitigation is not available, it is essential to consider effective contingency planning instead. Because of project constraints (e.g., financial pressures), sometimes it is not possible to mitigate a risk even though the risk might be in the top risk list. In this situation, a team might need to postpone implementing risk mitigation until more definitive effects of a risk are evident. To facilitate this, a team can choose to use a mitigation trigger. A trigger is a defined event, situation, or condition that, when it occurs, invokes a respective plan or action. A mitigation trigger invokes the start of the respective mitigation efforts. A team establishes mitigation triggers based on the type of risk or the type of impact that will be encountered. There are three types of triggers:

ContingencyRisk contingency planning involves creation of one or more fallback plans that are activated if efforts to prevent the adverse event fail. Contingency plans are necessary for as many risks as is prudent, including those that have mitigation plans. They address what to do if a risk is realized. This means focusing on the consequence and minimizing its impact. To be effective, a team should make contingency plans well in advance. Each contingency plan is invoked by satisfying criteria defined within an associated contingency trigger. It is important for a team to agree on contingency triggers and their values with the appropriate stakeholders as early as possible so that there is no delay committing budgets or resources needed to carry out a contingency plan. Risk Scheduling ActivitiesRisk scheduling is the process of integrating risk management plan tasks into a project schedule. Scheduling risk management and control activities does not differ from the standard approach recommended by MSF toward scheduling project activities in general. It is important that a team understand that risk control activities are an expected part of a project and are not an additional set of responsibilities to be done on a voluntary basis. All risk activities should be accounted for within project scheduling and status reporting processes. OutputsThe outputs from risk planning and scheduling should include specific risk action plans employing one of the six approaches discussed earlier at a step-by-step level of detail. A master risk list should be updated to reflect the additional information included in mitigation and contingency plans. It is convenient to summarize risk management plans into a single document. Updated Master Risk ListTop risks within a master risk list are updated with additional information derived from risk exposure reduction efforts as well as action plan development. Because risk action plans are sometimes complex and detailed, they are often put in a separate document. Risk Action PlanA risk action plan outlines an approach (e.g., avoid a risk) and tasks necessary to handle a stated risk. Table 5-11 lists examples of simple action plans associated with risk statements, where a selected approach is mitigation with contingency as the backup approach should mitigation not work.

Should the selected approach be mitigation with contingency as backup (which is the most common approach), a team should consider including the following information when developing their action plans:

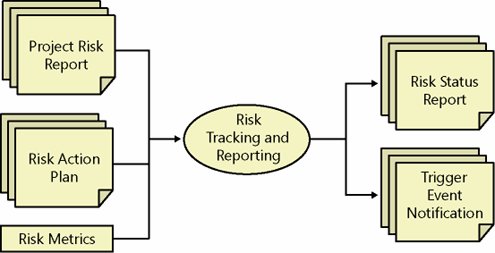

Updated Project Schedule and Project PlanPlanning documents related to risk should be integrated into the overall project planning documents. A master project schedule should be updated with new tasks generated by the action plans. Step 4: Track and Report Risk StatusRisk tracking and reporting is the fourth step in the MSF Risk Management Process. Risk tracking and reporting is the proactive process of managing risk prevention (e.g., mitigation plan execution) and reporting associated status. Risk tracking is the monitoring function of a risk action plan. It also ensures that assigned tasks implementing preventative measures are completed in a timely fashion within project resource constraints. Risk reporting provides updated status on risk metrics and provides notification of triggering events. Risk tracking and reporting is depicted schematically in Figure 5-6. Figure 5-6. Risk tracking and reporting GoalsThe goals of the risk tracking and reporting step are these:

InputsThe principal inputs to the risk tracking and reporting step are the following:

Depending on specific project metrics being tracked by a team, other sources of information such as project tracking databases, source code repositories or check-in systems, or even human resources management systems can provide tracking data for a project team. Risk Tracking ActivitiesRisk tracking activities include monitoring risk metrics and triggering events to ensure that planned risk actions are working. A team executes the actions in a mitigation plan as part of the overall team activity. Progress toward these risk-related action items and relevant changes in trigger values are captured and used to create specific risk status reports for each risk. Risk Reporting ActivitiesRisk status reporting provides a project team and stakeholders with regular, detailed updates of project risks. The particulars of who, what, when, and how to report risks should be encompassed in a project communications plan. At a minimum, risk status reports should consider four possible risk management situations for each risk:

For external reporting, a team should report the top risks and then summarize the status of risk management actions. It is also useful to show the previous ranking of risks and the number of times each risk has been on the top risks list. As a project team takes actions to manage risks, the total risk exposure for a project (i.e., the cumulative exposure of the top risks) should begin to approach acceptable levels. OutputsThe main outputs from this step are regular, detailed risk status reports and notifications of any contingency trigger conditions that have been met, which subsequently invoke a risk's contingency plan (i.e., a risk has been realized). Risk Status ReportThe purposes of a risk status report are to communicate changes in risk status and report progress of mitigation planning activities. Typically, a communications plan calls for a project team status report and a higher-level summary for people outside of a project team. Information that is useful in a project team risk status report includes the following:

Another type of risk status report is for people external to a project team (e.g., executives and stakeholders). Useful information to include in this summary risk status report includes the following:

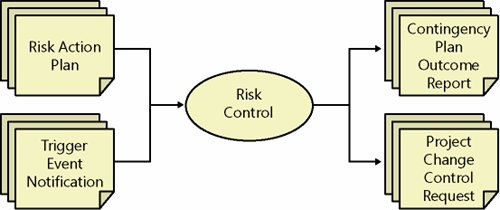

Step 5: Control RiskThe fifth step in the MSF Risk Management Process is risk control. Risk control is the reactive process of managing risk contingency plan execution and reporting associated status. Risk control also includes initiation of project change control requests when changes in risk status or risk plans could result in changes in project features, resources, or schedule. The inputs and outputs of this step are depicted in Figure 5-7. Figure 5-7. Risk control GoalsThe goals of the risk control step are these:

InputsThe inputs to the risk control step are notifications of what triggers have involved their respective contingency plans and risk action plans that detail contingency plan activities to be carried out by project team members. Risk Control ActivitiesRisk control is the process of executing risk contingency plans for realized risks and providing updated status for affected risks and overall changes to risk analyses, priorities, plans, and schedules. Risk control also includes initiation of project change control requests when changes in risk status or risk plans could result in changes in project features, resources, or schedule. Risk control activities should use standard project management processes for initiating, monitoring, and assessing progress along a planned course of action. Specific details of risk plans vary from project to project, but a general process for task status reporting should be used. It is important to maintain continuous risk identification to detect secondary risks that might appear or be amplified because of the execution of a contingency plan. OutputsThe outputs from a risk control step are project change control requests and contingency plan outcome reports. Change Control RequestA change control request is documentation of and a request for permission to change a solution or delivery of a solution. A change might be necessary as part of contingency plan execution. Contingency Plan Outcome ReportA contingency plan outcome report documents the results, status, and lessons learned from contingency plan execution. This information likely will become part of a project and enterprise risk knowledge base and will be rolled into a risk status report, as discussed previously. It is important to capture as much information as is possible about problems when they occur or about a contingency plan when it is invoked to determine the efficacy of such a plan or strategy on risk control. Step 6: Learn from RisksLearning from risks from a strategic, enterprise, and organizational perspective is the sixth and last step in the MSF Risk Management Process. This step extracts, documents, and communicates project risk lessons learned and captures relevant project artifacts in an enterprise-wide risk knowledge base. This step, sometimes referred to as risk leverage, emphasizes the value that is returned to an organization by increased capabilities and maturing at team, project, and organizational levels and improvement of a risk management process. Risk learning should be a continuous activity throughout the MSF Risk Management Process and can begin at any time. It focuses on three key objectives:

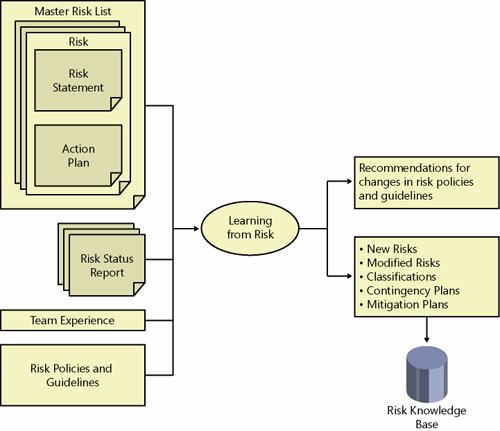

Risk review meetings provide a forum for learning from risk. They should be held on a regular basis, and, like other MSF reviews, they benefit from advance planning; development of a clear, published agenda in advance; participation of all participants; and free, honest communication in a "blame-free" environment. Figure 5-8 depicts a learning step. Figure 5-8. Learning from risk GoalsThe goals of the learning step are these:

InputsLearning comes from and as a result of a combination of many inputs. Basically, learning comes from all aspects of risk management. Risk Learning ActivitiesLearning spans the range from tangible improvements in a risk management process to less tangible personal team member growth. Learning needs to be captured, managed, and retained in such a way that others are able to draw meaning later. Capturing Learning About RiskHow does a team capture learning because learning comes in so many forms and with so many levels of learning? How do they enable personal learning, which is very different from institutional learning? One of the tangible areas of experiential refinement is risk classifications. Refining risk classification is a powerful means for ensuring that lessons learned from previous experience are made available to teams performing future risk assessments. Two key aspects of learning associated with risk classifications are as follows:

Managing Learning from RisksOrganizations using risk management techniques often find that they need to create a structured approach to managing project risk. Otherwise, lessons learned identified by team members quickly fade away as teams refocus on the next project. Experience has shown that elements of successful learning management include the following:

Retaining Learning from RisksMost often, retaining lessons learned includes a knowledge base. It is one form of knowledge repository that can range from a simple collection of risk collateral (e.g., action plans) to a complex collaboration server that helps categorize and index the knowledge for faster identification and retrieval. Sometimes knowledge retention is as simple as the shared experience among a team. Like what has been said before about other parts of MSF, with risk knowledge management, keep it simple and do only as much as provides a compelling return on investment of time and effort. OutputsJust as there might be areas within risk management that team members learn from, those same areas might also benefit and be refined based on those lessons learned. For instance, a risk management process should be refined and matured to better fit an organization. Part of this maturation is typically getting better at retaining knowledge, usually within a knowledge base. The process of identifying and quantifying risk greatly benefits from risk lessons learned. As discussed at the beginning of this chapter, using risk classification is a great way to stimulate a team's thinking and to make sure a team considers enough risk areas. Risk Knowledge BaseA risk knowledge base is a key driver of continual improvement in risk management. It is a formal or informal mechanism by which an organization captures learning to assist in future risk management. Without some form of knowledge base, an organization might have difficulty adopting a proactive approach to risk management. A risk knowledge base differs from a risk management database, which is used to store and track individual risk items, plans, and status during a project. Context-Specific Risk ClassificationsRisk identification might be refined by developing risk classifications for specific repeated project contexts. For example, a project delivery organization might develop classifications for different types of projects. As more experience is gained on work within a project context, risks can be made more specific and associated with successful mitigation strategies. Please keep in mind that making risk classifications more specialized increases the potential that these classifications might not be applicable outside of a project.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 137