The Valid XML Document

Let's say I ask you to give me a well-formed document that describes your favorite jokes. You give me two documents, a short joke and a long one.

<?xml version="1.0"?> <favorite-joke author="Pate"> <one-liner>A duck walks into a bar and says to the bartender, "Gimme a shot of whisky and put it on my bill."</one-liner> </favorite-joke> |

The long joke has a more complex format than the first.

<?xml version="1.0"?> <duck_joke> <scene number="1"> A duck walks into a bar, goes up to the bartender, and says, "Do you have any grapes?" The bartender says, "No, this is a bar, of course we don't have any grapes." </scene> <scene number="2"> The next day, the duck walks into the bar, goes up to the bartender, and says, "Do you have any grapes?" The bartender says, "No, like I told you yesterday, we don't have any grapes. If you come in here one more time asking for grapes, I'm going to nail your webbed feet to that bar!" </scene> <scene number="3"> The next day, the duck walks into the bar, goes up to the bartender, and asks, "Do you have any nails?" The bartender says, "No, this is a bar, of course we don't have any nails." Then the duck says, "Do you have any grapes?" </scene> </duck_joke> |

Both of these documents contain enough information for a human to figure out the meaning of each element. The first document is clearly the author's favorite joke, and it is clearly a one-liner. We can see that the second document is a duck joke with three scenes. Both documents are well-formed, and an XML parser will not issue any errors when it reads them.

But what if I want to gather many documents like these together and write a program to load jokes into a database? The two documents here—and whatever documents I get from other people—are entirely useless to me. Why? Because there is no standard structure. There's no way to predict how the data will be arranged or even how a submitter will format their tags. Therefore, I can't write a program that can reliably interpret all the different jokes that might come in.

Even though the documents here are self-describing to a human, computers aren't as smart as we are. They need some help in understanding the data before they can process it. Without a predefined formal structural definition, an XML document is only a text file.

To help the computer interpret these documents, I can create a predefined structure for the information and give that to you. A computer on your end can use that structural definition to guide your document creation. You then give me an XML document that is compatible with my database-loading program. This definition becomes a style guide for structure.

Style guides are not a new invention. Every journalist in the field gets a style guide that he uses to ensure that he follows the rules of the newspaper. This style guide will probably have policies for grammatical style, libel avoidance, and the overall tone of an article. A style guide will also indicate the desired structure for an article submission. For example, it might indicate that an article must consist of a headline, followed by a byline, followed by a dateline, an abstract, and an article body. The body, in turn, must consist of one or more paragraphs.

The journalist puts a piece of paper in the typewriter and starts typing his article. He types the headline, byline, and abstract, and then he starts writing paragraphs. He removes the paper from the typewriter and sends it downstairs to the copy editor.

The copy editor notices that the journalist forgot the dateline. She sends the paper back upstairs. What happened here? Two humans were involved in this error, an expensive proposition. If only this journalist had a guardian angel to watch over the keyboard, help him create the document to spec, and keep him from removing the paper until he follows all the rules. For implementers of XML, that guardian angel is valid XML, and the set of rules is the schema.

The Document Type Definition

As you learned in the beginning of this chapter, the XML spec defines a valid XML document thusly:

An XML document is valid if it has an associated document type declaration and if the document complies with the constraints expressed in it.

So, what's a document type declaration?

The document type declaration tells the XML parser where to find a set of rules against which a document can be checked. Where does this set of rules come from? Someone determines the structure of the members of a particular class of documents and makes that structural description available to the parser. The parser reads the structural description, and then parses the document to determine whether it is wellformed. In XML 1.0, the set of rules pointed to by the document type declaration (DOCTYPE) is called the document type definition (DTD).

The well-formed document now has an extra burden: not only must it adhere to the well-formedness constraints that I listed previously, but it also must be structured according to this user-created structural description.

This structural description is called a schema. In XML 1.0, the only type of schema allowed is the DTD. The DTD was taken straight from SGML and slimmed down to get rid of some optional features and hard-to-implement bits.

A DTD for the first Joke document looks like this:

<!ELEMENT Joke (Setup, Punchline) > <!ATTLIST Joke author CDATA #REQUIRED firstTold CDATA #IMPLIED > <!ELEMENT Setup (#PCDATA) > <!ELEMENT Punchline (#PCDATA) > |

To create a valid XML document, I place the document type declaration on top of the document to indicate that the physical file containing the DTD—named Joke.DTD—should be read first, and that the Joke document should be validated according to that structure.

<?xml version="1.0"?> <!DOCTYPE Joke SYSTEM "Joke.dtd"> <Joke author="Groucho Marx"> <Setup>Outside of a dog, a book is man's best friend</Setup> <Punchline>Inside of a dog, it's too dark to read.</Punchline> </Joke> |

This book is probably the only XML book on the shelf that will not attempt to teach you the DTD. Many XML resources are available to teach you the syntax and meaning of the various parts of the DTD.

The DTD was designed to describe legacy document information. We have 15 years of experience in SGML and XML indicating that the DTD works as designed. However, several factors limit the DTD's applicability in e-business transactions.

First, DTD is not written using XML syntax. As you can see from the preceding example, the DTD uses a terse syntax with strange words such as #PCDATA and ATTLIST. Such syntax is not consistent with the sixth XML design goal: "XML documents should be human-legible and reasonably clear."

Another problem is that the DTD has just a single useful data type: TEXT. We can define an element as containing other elements or text. What if we want to validate that the contents of a document form a valid number or a valid date? The parser verifies only that an element contains characters. It's the application's job to verify that a particular string of characters forms a valid date.

But remember that one of the advantages of an XML document is that XML separates data from the processes that act on the data. Thus, several different applications might process the same XML document. Each application that touches the document bears the burden for verifying that a particular element content or attribute value contains a particular data type. Wouldn't it be better if the parser verified the correctness of the data types before the application got the document?

The last major problem with the DTD is that a document can have only one document type to describe the entire document, making it fairly inflexible. The DTD was created in the days of top-down bureaucratic document management. This is good when you need to make sure that documents conform to very rigid standards. For example, all aircraft maintenance manuals must have the same predictable structure because safety is at stake. Safety engineers, maintenance personnel, and even legal departments had a say in this structure's design. Failure to adhere to the approved structure could have disastrous consequences.

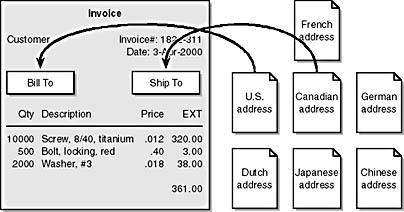

The top-down design approach doesn't work quite so well for a business document such as an invoice or medical record though. Consider an invoice, such as the one shown in Figure 4-1. A typical invoice has some header information such as invoice number, date, and customer number. Then there's a place for the address of the vendor, followed by an area that describes the items ordered.

We can use this invoice to bill customers all over the world. Part of the invoice will be the same no matter where we send it. The customer number, invoice number, and line items are all objects common to all vendors. However, what if we do business with a company in the United States? In the United States we use a street address structure that has a city, state, and zip code. The Canadian structure uses a city, province, and postal code. Japan, Germany, and France all have different addressing standards. If we were forced to define our invoice using the all-inclusive, top-down approach that the DTD requires, the invoice would be overly complex.

Wouldn't it be nice to describe an invoice with a single schema, and then "plug in" a second schema from a collection of schemas that describe address blocks? We can do exactly that with the new XML schema syntax and namespaces.

Figure 4-1. A business document can include other documents. This invoice can be sent to many different countries, each of which has a different way of specifying physical address information.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 150