6 - Infectious Diseases

Editors: Schrier, Robert W.

Title: Internal Medicine Casebook, The: Real Patients, Real Answers, 3rd Edition

Copyright 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Chapter 6 - Infectious Diseases

function show_scrollbar() {}

Chapter 6

Infectious Diseases

Robert T. Schooley

Urinary Tract Infection

What host factors lead to the development of urinary tract infections (UTIs), and how are these factors different for men and women?

What organisms commonly cause lower UTIs?

What are the signs and symptoms of lower UTI, and how do these differ from those of pyelonephritis?

Discussion

What host factors lead to the development of UTIs, and how are these factors different for men and women?

Improper hygiene, sexual activity, incontinence, urinary tract instrumentation, contraceptive diaphragms with or without spermicides, diabetes mellitus, a genetic predisposition, and dehydration are all factors that can increase the

P.221

likelihood of a UTI. Most UTIs are caused by endogenous flora originating from the gastrointestinal tract. These organisms have been shown to colonize the vaginal introitus and periurethral area before UTI occurs. Women who wipe their perineal area from the posterior to anterior direction after defecation, rather than vice versa, or those who are incontinent of stool, may be subject to more frequent colonization of the short female urethra with Enterobacteriaceae. The longer urethra in men makes access to the bladder more difficult for enteric flora; however, this flora may be introduced to the normally sterile bladder area as the result of Foley catheterization or cystoscopy. One of the natural defenses against cystitis after urethral colonization is the mechanical flushing of the urinary bladder, which takes place during urination. Obviously, anyone who is dehydrated cannot benefit frequently from this natural defense mechanism. Sexual activity can predispose women to acquiring UTI. In addition, as the result of a poorly understood mechanism, women who use a diaphragm for contraception, especially with spermicides, seem to be more susceptible to urethral colonization and UTI. It has been proposed that this predisposition might be due, at least in part, to a shift in vaginal microbial flora caused by the activity of spermicides. Diabetes mellitus may predispose to UTI through a variety of mechanisms, including the defective chemotaxis of leukocytes, phagocytic defects, and enhanced growth conditions for bacteria. Genetically determined factors, such as the type and number of receptors on uroepithelial cells to which bacteria may attach, also appear to heighten susceptibility to UTIs.What organisms commonly cause lower UTIs?

Escherichia coli causes most (up to 80%) of the community-acquired uncomplicated UTIs, with Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Proteus organisms more likely to cause complicated or hospital-acquired UTIs. These are all gram-negative organisms that usually originate from the patient's own gastrointestinal flora. There are, however, several gram-positive organisms that occur as urinary pathogens. Staphylococcus saprophyticus, a coagulase-negative Staphylococcus organism, causes 20% or more of the UTIs in women 16 to 35 years of age. Streptococcus faecalis causes 2% to 3% of the UTIs in otherwise healthy young women. When Staphylococcus aureus is found in the urine, a bacteremic infection of the kidney should be suspected.

Chlamydia, Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are sexually transmitted pathogens that usually cause vaginal or cervical infections; however, they may be implicated in cases of acute urethral syndrome in which Gram's-stained urine samples exhibit pyuria without bacteriuria.

Pseudomonas and Serratia are more commonly nosocomial gram-negative pathogens that are not usually seen in community-acquired, uncomplicated UTIs.

What are the signs and symptoms of lower UTI, and how do these differ from those of pyelonephritis?

The term lower UTI actually encompasses cystitis and urethritis, as well as prostatitis. Symptoms classically include urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria,

P.222

and suprapubic discomfort. Signs may include fever, cloudy or foul-smelling urine, and hematuria. Because upper UTIs (i.e., pyelonephritis, acute lobar nephritis, and a perinephric abscess) often start as cystitis, the same signs and symptoms may exist; however, the fever is usually more severe, and may be accompanied by shaking chills. An upper UTI is often accompanied by costovertebral angle tenderness on the involved side. Elderly people and those with diabetes may exhibit fewer signs and symptoms than otherwise normal hosts.

Case

A 19-year-old, sexually active woman presents to the emergency room complaining of a 2-day history of urinary frequency, burning, and urgency. She denies vaginal discharge or itching, fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, back pain, abdominal pain, or hematuria. She has no history of UTI or a sexually transmitted disease. She recently began using a diaphragm for birth control, and reports that her last menstrual period occurred 3 weeks ago. She has only one sexual partner, who denies penile discharge or burning on urination. On physical examination, she is noted to be afebrile with a normal blood pressure and pulse. There is no costovertebral angle tenderness. Her abdomen is soft and there is mild suprapubic tenderness in response to palpation. A urinalysis reveals 1+ protein, 2+ leukocytes, and 1+ blood. The urine pH is 5.6. Gram's staining of an unspun urine specimen reveals abundant polymorphonuclear leukocytes and moderate gram-negative rods. A clean-catch urine specimen is sent to the microbiology laboratory for culture.

The emergency room physician diagnoses an uncomplicated UTI and prescribes trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), one double-strength tablet twice a day for 3 days.

What other therapeutic options would have been appropriate in this patient?

What can this woman do to help prevent recurrent UTIs?

Should this woman's sexual partner be evaluated for UTI?

Was the Gram's staining an important diagnostic test, and in what way did the findings alter the management of this case?

What is the value of knowing the urine pH in this setting?

What other diagnostic or laboratory tests should have been performed?

What would be an appropriate analgesic for a patient with UTI who is experiencing severe urethral discomfort?

What side effects of therapy should this woman know about?

What possible consequences could arise if this woman does not comply with therapy?

Case Discussion

What other therapeutic options would have been appropriate in this patient?

TMP-SMX remains the drug of choice for the empirically based treatment of uncomplicated UTIs. For sulfa-allergic patients, ampicillin, amoxicillin, a first-generation cephalosporin, or a quinolone is the appropriate alternative. Therapy may then be modified on the basis of the urine culture results and the sensitivities of the infecting organism. Enterococci are not susceptible to either TMP-SMX or

P.223

cephalosporins, which points out the utility of performing urine Gram's staining when deciding on antibiotic therapy. The prevalence of ampicillin-resistant E. coli may be as high as 30% in some communities, and this needs to be considered when selecting an appropriate antibiotic. S. saprophyticus responds to ampicillin, TMP-SMX, and the quinolones. In the past, treatment of lower UTIs for 5 to 7 days was recommended. Short course therapy with agents that achieve high and sustained urinary concentrations (single dose with one or two double-strength TMP/SMX or 3 g of amoxicillin) will usually suffice for uncomplicated infections. Failures of short course therapy are indications that complicating factors requiring more extensive evaluation might be present. In general, single-dose therapy is contraindicated in patients with known anatomic or functional abnormalities, or with immunocompromising diseases such as diabetes mellitus. After single-dose therapy urine cultures should be performed 1 to 2 weeks later, to document the cure. In the event of treatment failure, a longer course of the appropriate antibiotic should be administered and an evaluation of potentially complicating factors should be undertaken.Regardless of the pathogen and the choice of antibiotics, aggressive oral hydration is a reasonable recommendation in the management of an uncomplicated UTI. Although there is no evidence that hydration improves the results of appropriate antimicrobial therapy, it does dilute the bacteria and removes infected urine by frequent bladder emptying.

What can this woman do to help prevent recurrent UTIs?

Some women find that switching to another method of birth control considerably reduces the frequency of recurrent bacterial UTIs. Thorough cleansing of the perineal area before sexual relations may decrease the incidence of postcoital UTI in those prone to UTI; however, most patients find this to be an impractical and not completely effective preventive measure.

Choosing another method of birth control may not be necessary for most women if they remember to drink a large glass of water before intercourse and void after intercourse; however, studies have shown that diaphragm usage is an independent risk factor for UTI. Regular antibiotic prophylaxis should be reserved for those patients with a history of multiple recurrent UTIs, or complicated UTI or upper tract infections, or for immunocompromised hosts. The disadvantages of ongoing prophylaxis include the development of drug-related side effects and colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms.

Should this woman's sexual partner be evaluated for UTI?

No. Although lower UTIs in women are associated with sexual activity, this is not a sexually transmitted disease. The infecting organisms are usually endogenous flora. Healthy men without predisposing factors such as urinary tract instrumentation or diabetes mellitus rarely get lower UTIs. Bacterial prostatitis does not put his sexual partner at risk for cystitis.

Was the Gram's staining an important diagnostic test, and in what way did the findings alter the management of this case?

When bacteriuria is found in Gram's-stained, uncentrifuged urine, this is a very specific finding for the diagnosis of UTI. The finding of microscopic bacteriuria corresponds to urine culture colony counts of 105/mL in more than 90% of such

P.224

specimens. Distinguishing between gram-positive and gram-negative infections can be quite useful in making therapeutic decisions.What is the value of knowing the urine pH in this setting?

Alkaline urine may be caused by infection with Proteus species, which produce urease. The presence of nonalkaline urine in this patient makes infection with a urea-splitting organism unlikely.

What other diagnostic or laboratory tests should have been performed?

The physical examination and diagnostic studies performed in an emergency room setting should be directed toward elucidating the nature of the patient's chief complaint and history. A pelvic examination would be appropriate if the patient had reported symptoms of increased vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, or exposure to a known sexually transmitted disease in the partner. The indications for performing cultures for sexually transmitted pathogens are similar to those for a pelvic examination. Chlamydia, Ureaplasma, N. gonorrhoeae, or Mycoplasma infection should have been considered in this patient if no organisms were seen on the Gram's-stained urine specimens, or if subsequent routine bacterial cultures grew no organisms.

Intravenous pyelography and a renal ultrasound examination should be reserved for when a complicated UTI or upper UTI such as pyelonephritis is suspected. A pregnancy test should be performed in any woman of childbearing age before prescribing an antibiotic that may be contraindicated in pregnancy.

What would be an appropriate analgesic for a patient with UTI who is experiencing severe urethral discomfort?

Phenazopyridine hydrochloride is a urinary tract analgesic agent that exerts a topical analgesic effect on the mucosa of the urinary tract through an unknown mechanism of action. The side effects are minimal, and include the urine acquiring a red or orange color that may stain fabric. It is usually not necessary to prescribe more than a 2-day supply to patients with uncomplicated UTIs who are receiving appropriate antibiotic therapy. Opioid analgesics are relatively contraindicated in UTI because they may cause acute urinary retention.

What side effects of therapy should this woman know about?

Vaginal candidiasis commonly develops after antimicrobial therapy because antibiotics eliminate much of the normal vaginal flora and create an ideal environment for the overgrowth of Candida albicans. Hypersensitivity reactions may occur with any antibiotic; however, TMP-SMX may rarely also be associated with interstitial nephritis, aseptic meningitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or erythema multiforme. A careful history to rule out known drug allergy is important.

What possible consequences could arise if this woman does not comply with therapy?

The consequences of noncompliance with therapy include continuing symptoms, the induction of antibiotic-resistant strains of microorganisms, and, most important, ascending infection leading to acute pyelonephritis or even a perinephric abscess.

Suggested Readings

Bent S, Saint S. The optimal use of diagnostic testing in women with acute uncomplicated cystitis. Am J Med 2002;113(Suppl 1A):20S.

P.225

Dunagan WC, Ridner ML. Manual of medical therapeutics, 26th ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1995:257.

Fihn SD, Latham RH, Roberts P, et al. Association between diaphragm use and urinary tract infection. JAMA 1985;254:240.

Hooten TM, Scholes D, Hughes JP, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infections in young women. N Engl J Med 1996;335:468.

Latham RH, Running K, Stamm WE. Urinary tract infection in young adult women caused by Staphylococcus saprophyticus. JAMA 1983;250:3063.

Leibovici L, Alpert G, Laor L, et al. Urinary tract infections and sexual activity in young women. Arch Intern Med 1987;147:345.

Norrby SR. Short term treatment of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections in women. Rev Infect Dis 1990;12:458.

Rubin RH, Fang LST, Jones SR, et al. Single-dose amoxicillin therapy for urinary tract infection. JAMA 1980;244:561.

Sobel JD, Kaye D. Urinary tract infections. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 6th ed. New York: Elsevier Science, 2005:875.

Stamey TA. Pathogenesis and treatment of urinary tract infections. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1980.

The Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

What are the principles of antiretroviral chemotherapy?

When should antiretroviral chemotherapy be started?

What are the most important human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1 associated opportunistic infections, and the treatments used in the HIV-1 infected individuals who live in developed countries?

Discussion

What are the principles of antiretroviral chemotherapy?

HIV-1 associated morbidity and mortality is the direct result of immunosuppression mediated by viral replication. The goal of antiretroviral chemotherapy is to drive plasma HIV-1 levels to below the limits of detection with the most sensitive available assay. This approach affords two major benefits: (a) Successful suppression of viral replication arrests destruction of the immune response and allows for immune reconstitution. This, in turn, results in a dramatic decline in HIV-1 associated morbidity and mortality. (b) The emergence of drug resistance can be eliminated or greatly reduced by driving viral replication rates to extremely low levels.

Suppression of plasma HIV-1 RNA to levels of 20 copies/mL is currently best achieved through the use of a combination regimen containing at least three agents. The inclusion of multiple agents is required both for potency and for interposing a significant genetic barrier to the virus with respect to the emergence of resistance. HIV-1 replication occurs at the rate of approximately 10 billion viral particles per day in each infected person. With the

P.226

replicative infidelity of HIV-1's reverse transcription mechanism, this high level of replication rapidly results in the creation of a diverse quasispecies of virus. Therefore, it is likely that at the institution of therapy, viral variants exist that are resistant to each currently available agent. The use of multiple agents with nonoverlapping resistance mechanisms requires the virus to make multiple genetic changes in each virion in order to persist in the presence of all agents in the regimen.At present, reduction of HIV-1 RNA to 20 copies/mL is best achieved with the selection of two nucleoside analogs usually administered as fixed dose combinations (and an anchor drug efavirenz or a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor). Although there is no single regimen that is appropriate for all patients, the nucleoside combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine with efavirenz has become the most frequent initial combination regimen. The recent introduction of a single tablet containing these two nucleosides and efavirenz has provided the first once-daily single pill antiretroviral regimen. Other fixed-dose nucleoside combinations, including either zidovudine and lamivudine or abacavir and lamivudine, may also be used in combination with efavirenz.

Although efavirenz is potent and well tolerated in most patients, it cannot be used in 15% to 20% of patients. Efavirenz is associated with central nervous system (CNS) side effects that require up to 10% of patients to seek another drug. Efavirenz is also teratogenic and should not be used in sexually active women of childbearing age who are not using effective birth control methods. Because transmission of drug-resistant viruses is increasingly frequent, it is best to check drug susceptibility before initiating antiretroviral drugs. Transmitted drug resistance to efavirenz is found in approximately 10% of patients initiating therapy for the first time in certain locations in the United States and Europe. In patients for whom efavirenz is not an optimal choice, a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor (usually r/lopinavir or r/atazanavir) is generally the best initial choice. Appropriate management of antiretroviral chemotherapy is both an art and a science that is best accomplished by physicians with substantial experience in management of patients with HIV-1 infection.

When should antiretroviral chemotherapy be started?

There is no single answer that is appropriate for every patient. Ongoing viral replication is always damaging to the immune response of the host. On the other hand, current antiretroviral regimens may be associated with side effects, and require significant discipline to achieve the level of viral suppression associated with durable success. As CD4 cell counts decline, patients are at greater risk for HIV-1 associated opportunistic infections. Rising plasma HIV-1 RNA levels are associated with more rapid immunologic and clinical disease progression. Adequate suppression of HIV-1 is best achieved in patients with high CD4 cell counts and low plasma HIV-1 RNA levels. Therefore, all things being equal, it could be argued that early institution of therapy is associated with the best chance of long-term success. The desire to start therapy early must be balanced by a consideration of long-term toxicities and the commitment of the patient to strict adherence of the regimen chosen. In general, the urgency to

P.227

start therapy increases as CD4 cell counts fall and the plasma HIV-1 RNA levels rise. Most experts recommend treatment for any patient with HIV-1 related symptoms and that the therapy be started for asymptomatic HIV-1 infected persons as their CD4 cell count passes into the 250 to 350 cell/mL range.What are the most important HIV-1 associated opportunistic infections, and the treatments used in the HIV-1 infected individuals who live in developed countries?

In general, the risk of various HIV-1 related infections increases with disease progression and declining CD4 cell counts. Two notable exceptions to this rule, however, are pneumococcal pneumonia and tuberculosis. All HIV-1 infected patients are at increased risk for acquiring pneumococcal pneumonia and sepsis. Whether the administration of pneumococcal vaccine can prevent or lessen the severity of pneumococcal disease in these patients has not been proved, but the current practice is to administer pneumococcal vaccine to all HIV-1 infected patients whose CD4 lymphocyte counts exceed 500/mm3. The response to vaccination in patients with counts of less than 500/mm3 is likely to be enhanced if they are on effective antiretroviral therapy at the time of vaccination.

Tuberculosis is one of the few HIV-1 related infections that is transmissible to immunocompetent persons. HIV-infected persons are at increased risk for acquiring tuberculosis regardless of the stage of their HIV-1 infection. Because patients with HIV-1 infection have reduced cellular immunity, a threshold of 5 cm is considered to be a positive tuberculin skin test. As the CD4 cell counts fall, patients may become anergic and the tuberculin skin test further loses it sensitivity.

Oral candidiasis (thrush) most frequently occurs when the CD4 lymphocyte count falls below 300/mm3. Thrush can usually be treated with topical antifungal agents (nystatin swish and swallow, or clotrimazole troches), but more severe cases, especially when esophageal lesions are present, may require systemic antifungal agents such as fluconazole.

Early in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic, Pneumocystic jiroveci (formerly carinii) pneumonia was the most common AIDS-defining illness. With the advent of effective prophylactic regimens, this illness has become much less frequent. Pneumocystis pneumonia is usually treated with TMP-SMX. Alternatively, intravenous pentamidine, oral trimethoprim/ dapsone, or oral atovaquone can be used in sulfa-allergic patients.

HIV-1 infected persons with less than 200 CD4 lymphocytes/mm3 are at risk for several types of CNS infections. One of the most common causes of intracranial masses in HIV-1 infected patients, Toxoplasma gondii, is treated with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine. Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, and Coccidioides immitis can cause CNS disease or disseminated disease in HIV-1 infected patients; infection with these pathogens is usually treated with amphotericin B.

Patients with less than 50 CD4 lymphocytes/mm3 are at risk for suffering disseminated infection with Mycobacterium avium [mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)] or ocular or systemic cytomegalovirus infections. Disseminated

P.228

MAC is commonly manifested clinically by the appearance of systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats, and anemia). Treatment with a combination of two or three active agents is required for MAC infection. Cytomegalovirus retinitis presents with painless loss of vision and may be accompanied by systemic evidence of infection, manifest by fever, weight loss, or gastrointestinal symptoms. Treatment with ganciclovir (or valganciclovir), foscarnet, or cidofovir is usually effective.

Case

A 32-year-old woman is found to be HIV-1 seropositive at the time of a life insurance physical examination. The patient has had no prior serious medical illnesses although she has experienced increased vaginal itching during the last year. Her physical examination is normal except for vaginal thrush. Her social history reveals that she has been married to the same man for the last 3 years. He is also healthy. Upon detailed questioning, he admitted to having experimented with sex with men on several occasions while traveling to San Francisco 8 years earlier. He is subsequently found to be HIV-1 seropositive with a CD4 cell count of 860 cells/mm3 and a plasma HIV-1 RNA level of 13,000 copies/mL.

The laboratory evaluation reveals that she has a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antibodies to HIV-1. HIV-1 seropositivity was confirmed by a Western blot assay. Her purified protein derivative (PPD) is negative, as is her serology for T. gondii. Her rapid plasma reagin (RPR) is negative. Her hematocrit is 43. Her white blood cell count is 5,200/mm3. Her CD4 cell count is 340 cells/mm3. Her plasma HIV-1 RNA level is 143,000 copies/mL.

What would you recommend to her with respect to antiretroviral chemotherapy?

How would you alter your recommendations if you learned she is pregnant at the time of presentation? If she were pregnant, is it likely that her child would be infected?

What would you recommend to her husband with respect to antiretroviral chemotherapy?

Case Discussion

What would you recommend to her with respect to antiretroviral chemotherapy?

You should recommend to her that she initiate antiretroviral therapy. Although her CD4 cell count is in a range that would prompt some practitioners to recommend deferring therapy, the presence of vaginal thrush is a clinical indicator of HIV-1 disease and places her at greater risk for an opportunistic infection than a woman with the same CD4 cell count and no symptoms. Therapy should not be initiated until a viral susceptibility test result has been obtained. In her case, it reveals that her virus is resistant to efavirenz, likely reflecting the acquisition of the drug-resistant virus from her husband. Because of this, you should recommend a regimen that uses a boosted protease inhibitor as the anchor drug such as tenofovir, emtricitabine, and r/lopinavir.

How would you alter your recommendations if you learned she is pregnant at the time of presentation? If she were pregnant, is it likely that her child would be infected?

The general approach to antiretroviral chemotherapy in pregnancy should be the same as it is in a nonpregnant woman. Effective management of an infected

P.229

woman requires close collaboration among an internist or infectious disease specialist with experience using antiretroviral therapy, an obstetrician with experience dealing with HIV-1 infected mothers, and a pediatrician with HIV-1 expertise. The dual goals of therapy in this setting are to suppress viral replication to benefit the mother and to decrease the risk of transmission of HIV-1 to her baby. With her CD4 cell count and plasma HIV-1 RNA level, she is at risk for disease progression over the next several years and, as mentioned in the preceding text, most experts would recommend antiretroviral chemotherapy to her once she is through her first trimester of pregnancy. Although there is no evidence that tenofovir places fetuses at risk, there is more experience with zidovudine and lamivudine in pregnancy; so it would be preferable to use these agents instead of tenofovir and emtricitabine. Because her virus is not susceptible to efavirenz, it would not be used. Nonetheless, even if her virus were susceptible to the drug, it should not be used in pregnancy because of concerns about teratogenicity. Although d4T and ddI are used less frequently these days, they should be avoided whenever possible in pregnant women because of lactic acidosis, hepatic steatosis, and pancreatitis. Nevirapine has been associated with severe hepatitis, especially in women with CD4 cell count more than 250/mm3 and should be avoided in this patient for that reason. Therefore, she would best be treated with a protease inhibitor as the anchor drug in her regimen. Although nelfinavir is often used in pregnancy, concerns about its potency dampen the enthusiasm for it even in this setting. R/lopinavir is a very reasonable choice, although there are data that suggest increased metabolism of lopinavir during pregnancy. Therefore, drug levels should be followed-up.Before the advent of antiretroviral chemotherapy, the likelihood of transmitting HIV-1 from mother to child was in the range of 25%. Zidovudine monotherapy administered during the third trimester of pregnancy, coupled with intravenous zidovudine during delivery and 6 weeks of zidovudine for the infant, reduced the risk of perinatal transmission to 8%. More potent contemporary antiretroviral chemotherapeutic regimens have reduced this risk to below 1%. The goal of therapy in the mother should be to reduce plasma HIV-1 RNA levels to less than 20 copies/mL by delivery. The baby should also receive antiretroviral chemotherapy as part of the perinatal transmission prevention strategy. The neonate should not be breastfed, regardless of the mother's plasma HIV-1 level, in view of the risk of transmission of HIV-1 by this route.

What would you recommend to her husband with respect to antiretroviral chemotherapy?

Her husband has been infected for more than 5 years and has maintained a low plasma HIV-1 RNA level and a near normal CD4 cell count. Although he is technically not a long-term nonprogressor because he has not been documented to be infected for more than 10 years, his plasma HIV-1 RNA level and CD4 cell count predict that his disease progression risk is very low. Most experts would not recommend antiretroviral chemotherapy to him at this point. Although antiretroviral chemotherapy is not indicated, he should undergo a full initial evaluation for HIV-1 including a PPD, an RPR, and T. gondii and cytomegalovirus serology and should be followed-up at 3- to 6-month intervals for evidence of a rising plasma HIV-1

P.230

RNA level and/or a falling CD4 cell count. He should also be vaccinated against pneumococcal disease. It would also be prudent to test his virus for resistance to antiretroviral drugs to guide selection of his regimen when he requires therapy. Even if his virus is found to be susceptible to efavirenz, it should not be relied upon in his case because it is presumed that his wife acquired her resistant virus from him and it is known that drug-resistant virus may be overgrown by wild type virus in the plasma. In these situations, the lifelong persistence of drug-resistant minor species variants leads to treatment failure if these agents are used.

Suggested Readings

Barnes PF, Bloch AP, Davidson PT, et al. Tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1644.

Carpenter CJ, Fischl MA, Hammer SM, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV Infection in 1998. JAMA 1998;280:78 86.

Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Pediatric ACTG Protocol 076 Study Group. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1173 1180.

Gallant JE, Staszewski S, Pozniak AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir DF vs stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-na ve patients: a 3-year randomized trial. JAMA 2004;292:191.

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents. AIDS Treatment Guidelines Panel of the Department of Health and Human Services, Web site (http://AIDSinfo.nih.gov), 2006.

Hammer SM, Saag MS, Schechter M, et al. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society USA Panel. JAMA, 2006;296:827 843.

Ho DD, Neumann AU, Perelson AS. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature 1995;373:123 126.

Kitahata MM, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA, et al. Physicians' experience with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome as a factor in patients' survival. N Engl J Med 1996;334(11):701 706.

Masur H, Ognibene FP, Yarchoan R, et al. CD4 counts as predictors of opportunistic pneumonias in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Ann Intern Med 1989;111:223.

Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV outpatient study investigators. N Engl J Med 1998;338:853 860.

Cellulitis

What factors predispose to the development of cellulitis?

What are the signs and symptoms of cellulitis?

What organisms most frequently cause cellulitis?

P.231

Discussion

What factors predispose to the development of cellulitis?

Although any person can acquire cellulitis, there are several factors that heighten the risk of this infection. Any compromise of skin integrity can introduce organisms into the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Therefore, surgical procedures, trauma, the placement of intravenous catheters, burns, and bite wounds are all factors that predispose to the development of cellulitis. The risk for development of cellulitis is also increased in hosts whose sensation is impaired, such as diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy whose ability to perceive and react appropriately to trauma is diminished.

Impaired arterial circulation also predisposes to the development of cellulitis. Host immune mechanisms, such as polymorphonuclear leukocytes and complement, are delivered through the circulation. Therefore, if the host circulation is impaired, normal immune mechanisms, which might easily eradicate an organism, cannot be mounted. This is why cellulitis is more frequent in patients with impaired arterial circulation, such as those with diabetes and smokers with peripheral vascular disease.

Patients whose venous and lymphatic drainage is compromised are also less able to clear bacteria from their bodies, and are consequently predisposed to cellulitis. Patients with chronic edema of the lower extremities are particularly vulnerable to cellulitis, which may spread very rapidly. A distinctive form of cellulitis has been found in patients whose saphenous veins have been removed for coronary artery bypass grafting. These patients, who most likely have both venous insufficiency and impaired lymphatic drainage, have been found to acquire cellulitis at the site of the saphenous venectomy. Frequently, the portal of entry for the infection is associated with tinea pedis. Besides the treatment of cellulitis, the tinea pedis should be treated with a topical antifungal agent.

Immunocompromised patients, such as those undergoing chemotherapy or transplantation procedures, are also vulnerable to cellulitis. The infection in these patients may be more difficult to diagnose because the characteristic symptoms and signs may be more subtle owing to the antiinflammatory properties of the immunosuppression.

What are the signs and symptoms of cellulitis?

The classic appearance exhibited by cellulitis is a hot, swollen, red, and tender skin lesion. The patient may be febrile, and regional lymphadenopathy is common. Acute lymphangitis, indicated by red streaks coursing up the patient's limb from the site of the cellulitis, signifies the spread of infection along subcutaneous lymphatic channels. Not all cases of cellulitis are associated with lymphangitis, but it may be the harbinger of serious systemic illness with bacteremia.

What organisms most frequently cause cellulitis?

The most common causes of cellulitis in general are group A streptococci and S. aureus. These gram-positive cocci are normal constituents of the

P.232

human skin flora and are easily introduced into wounds by trauma. Other streptococci may also occasionally cause cellulitis. Although one could rely on -lactamase resistant penicillins or cephalosporins in the past to treat most cases of community-acquired S. aureus infection, there has been a dramatic increase in methicillin-resistant S. aureus infection among patients with community-acquired infection in many parts of the United States. In these areas, presumptive therapy with vancomycin or linezolid, pending identification and susceptibility testing, is required. Practitioners must be aware of local conditions in making empiric antimicrobial choices.Less common pathogens may also be introduced into a wound by trauma. For example, soil-contaminated wounds may become infected with fungi or Clostridium species. Animal bite wounds may become infected with bacteria from the animal's mouth. Erysipeloid, caused by Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, is a cellulitis that affects people who handle salt-water fish, shellfish, poultry, meat, or animal hides. Various Vibrio species may cause cellulitis in people with wounds exposed to salt water or raw seafood.

Less frequently, cellulitis may be acquired through bacteremia. Rare cases of pneumococcal cellulitis have been reported. Immunocompromised patients may also acquire cellulitis by means of a bacteremia caused by organisms, such as C. neoformans or E. coli, that are not usual causes of cellulitis in healthy hosts.

Case

A 27-year-old man presents to the emergency room complaining of pain in his right hand. He was well until the previous day, when he sustained a deep scratch at the base of his right thumb while playing with his cat. He washed the wound and bandaged it tightly to stop the bleeding. Overnight, however, his palm began to swell, turned red, and became increasingly painful.

His blood pressure is 120/70 mm Hg, heart rate is 90 beats per minute, respiratory rate is 12 per minute, and temperature is 38.5 C (101.3 F). Physical examination findings are notable for a laceration on the right thenar eminence that is 2 cm long and 0.5 cm deep. The wound is partially crusted over with blood, with a small amount of serosanguineous discharge. The surrounding tissue is erythematous, hot, and exquisitely tender. There are two red streaks ascending the lower half of his anterior forearm. He has a tender, mobile, 1-cm lymph node in the right axilla. There is full range of motion without discomfort in any of the digits or the wrist of his right upper extremity. Neurologic examination of the hand reveals normal findings, and Allen's test result is normal.

The following laboratory data are found: white blood cell count, 15,000/mm3, with a differential count of 75% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 5% band forms, 17% lymphocytes, 2% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils. His serum chemistry values are normal. A radiographic study of the hand reveals no evidence of a foreign body or subcutaneous emphysema. Gram's staining of the serosanguineous discharge from the wound reveals large numbers of small gram-negative rods and a few gram-positive cocci in chains. Samples of the discharge and blood are sent for culture.

The patient was born and raised in the United States. He has been in good health before this illness and has no history of hospitalizations. He recalls having had a tetanus

P.233

booster shot 7 years ago. He has no history of allergic reactions to medications. His 7-year-old cat was also born and raised in the United States, has received all appropriate vaccinations, and is apparently healthy.

What infectious agents should be considered as possible causes of this patient's cellulitis?

What would be the most appropriate antibiotic treatment for this patient?

In addition to antibiotics, what other measures should be taken to treat this cellulitis?

Case Discussion

What infectious agents should be considered as possible causes of this patient's cellulitis?

Group A streptococci and S. aureus must always be considered as potential causes of cellulitis because they are the most common etiologic agents. In the event of animal bites or scratches, the oral flora of the animal may be an important source of infection as well. Pasteurella multocida is found in the oropharynx of 50% to 70% of healthy cats and 12% to 60% of healthy dogs. This gram-negative rod is frequently implicated in infections resulting from cat bites or scratches, and is found less often in wounds inflicted by dogs. Other important animal oral flora to consider in patients with bites and scratch wounds include aerobic and anaerobic streptococcal organisms, as well as gram-negative anaerobes such as Bacteroides species and Fusobacterium. Organisms found in soil, such as Clostridia species, may also be transmitted by scratches or bites.

The rapid tempo of this patient's illness, with the development of an exquisitely painful cellulitis within 24 hours of a cat scratch, is characteristic of P. multocida infection, although such a rapid course may also be seen in the setting of streptococcal infections. It would be unusual, however, for a staphylococcal infection to progress this rapidly. Moreover, the discharge from a staphylococcal infection would more likely be purulent than serosanguineous. The finding of many gram-negative rods on the Gram's-stained specimen of the wound discharge also suggests a P. multocida infection, or a gram-negative anaerobic infection. However, a few gram-positive cocci in chains were also found, making streptococcal infection a part of the differential diagnosis.

What would be the most appropriate antibiotic treatment for this patient?

This patient has a serious hand infection, along with an impending systemic illness. Anyone with such a serious hand infection should be hospitalized and receive intravenous antibiotics to prevent advancing infection, as well as to avert the potentially devastating consequences of suboptimal therapy. Penicillin is the drug of choice for P. multocida infections, and would also be effective for the management of both streptococcal and anaerobic infections. Therefore, intravenous penicillin would be the best antibiotic in this case. For patients who are allergic to penicillin, tetracycline is the best alternative drug for the treatment of P. multocida infections. The patient should also be seen in consultation with a hand surgeon to be certain that surgical intervention for drainage or decompression is not required.

In addition to antibiotics, what other measures should be taken to treat this cellulitis?

Overestimating the efficacy of antibiotics, and underestimating the critical roles played by debridement, drainage, wound elevation, and immobilization, are probably the most frequent mistakes made in the treatment of cellulitis. Drainage of a closed-space infection and removal of necrotic tissue are essential for curing any infection. Even when the appropriate antibiotics are administered, an infection can worsen if abscesses or necrotic tissue are not drained or removed. The reason for this is that abscesses and necrotic tissue are not well vascularized, making them inaccessible to both the antibiotics and the host immune mechanisms, such as polymorphonuclear leukocytes and complement, which are normally conveyed through the bloodstream. Therefore, in these inaccessible regions bacteria can freely multiply and, in some instances, such infection can result in sepsis and death despite an appropriate antibiotic regimen.

Abscesses tend to develop in the setting of P. multocida infection. In addition, the hand contains several physiologic spaces, such as the thenar eminence, that can serve as pockets of infection. Therefore, a P. multocida cellulitis of the hand may require surgical debridement and drainage. Incision of a hand wound should not be performed by a novice, because there is a great potential for damaging internal structures or creating wounds that would result in serious contractures. A hand surgeon should be consulted for this purpose.

The objective of elevation and immobilization in the treatment of cellulitis is to diminish the edema, which impedes the blood flow to an infected region. Elevation of the affected limb above the level of the heart is necessary to achieve optimal results. In the event of a lower extremity cellulitis, merely placing the affected limb on a chair while seated is not adequate because the abdominal contents still exert pressure on the lymphatic vessels in this position, thereby perpetuating the edema. In addition to the measures just described, this patient should receive a tetanus booster shot. Any patient with a bite or deep scratch wound who has not had a tetanus booster shot within the preceding 5 years should receive one.

P.234

Suggested Readings

Centers for Disease Control. Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis: guidelines for vaccine prophylaxis and other preventive measures. Ann Intern Med 1985;103:896.

Elliot DL, Tolle SW, Goldberg L, et al. Pet-associated illness. N Engl J Med 1985;313:985.

Francis DP, Holmes MA, Brandon G. Pasteurella multocida: infections after domestic animal bites and scratches. JAMA 1975;233:42.

Fridkin SK, Hageman JC, Morrison M, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in three communities. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1436 1444.

Goldstein EJC. Bites. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 6th ed. New York: Elsevier Science, 2005:3552.

Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Reig G, et al. Fourteen patients with necrotizing fasciitis caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Los Angeles. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1445.

Stevens DL, Herr D, Lamperis H, et al. Linezolid versus vancomycin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:1481.

P.235

Swartz MN, Pasternak MS. Cellulitis and subcutaneous tissue infections. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and practices of infectious diseases, 6th ed. New York: Elsevier Science, 2005:1172.

A Late Complication of Tuberculosis

What are the goals of the modern drug treatment of active pulmonary tuberculosis?

What factors are likely to promote relapse?

What factors are likely to foster the acquisition of drug-resistant disease?

Discussion

What are the goals of the modern drug treatment of active pulmonary tuberculosis?

Fundamental to the modern drug treatment of tuberculosis is the use of multiple-drug regimens. There are two goals to this approach.

The first object of multiple-drug treatment is to prevent the emergence of resistant organisms. The findings from early studies on the use of streptomycin dramatically demonstrated the futility of monotherapy, in that patients with severe disease showed an initial gratifying response to treatment, but after some weeks their condition began to deteriorate. Their sputum smears became positive for organisms once again, and drug-resistant disease developed. It is believed that monotherapy selects for, rather than induces the mutation of, resistant organisms. Therefore, the larger the population of organisms, the higher the likelihood that resistant organisms are present. Therefore, in the setting of an asymptomatic primary infection that involves few organisms, monotherapy (usually consisting of isoniazid) can be used safely as prophylaxis. In patients with active disease (especially cavitating pulmonary disease in which the burden of infection is immense), the probability of resistant organisms is high. Mutations leading to drug resistance are unlinked, however, so the use of two drugs (e.g., isoniazid plus rifampin) effectively prevents the emergence of secondary drug resistance (i.e., drug resistance acquired during treatment).

The second goal of therapy is to shorten the duration of treatment. To achieve a lasting cure in a high proportion of cases, regimens that comprise only rifampin plus isoniazid must be continued for 9 months. However, this can be reduced to 6 months by the addition of pyrazinamide for the first 2 months. Pyrazinamide is a powerful sterilizing drug that may exert its effect by acting on special subpopulations of organisms, such as those in a more acid environment. It has been shown that there is no additional benefit in continuing this expensive drug beyond the first 2 months.

A factor to be considered when planning multidrug treatment is that initial drug resistance exists when the disease is caused by organisms that are resistant to at least one drug before any treatment is given. When this is suspected on epidemiologic grounds, an additional drug (usually streptomycin

P.236

or ethambutol) is added to the regimen during the first 2 months, while the results of drug susceptibility studies are awaited. This approach reduces the risk of only one effective drug being given.What factors are likely to promote relapse?

Relapse (i.e., the endogenous reactivation of previously treated tuberculosis) is most likely to occur during the first year after the end of treatment and in those patients who initially had more extensive disease. Patients who discontinue their treatment early are most likely to have a relapse. Therefore, ensuring compliance with treatment is central to preventing relapse.

What factors are likely to foster the acquisition of drug-resistant disease?

For the reasons already outlined, drug-resistant organisms emerge when a patient effectively receives only monotherapy. This may occur for a variety of reasons, and the following illustrates how it can happen. A patient on rifampin plus isoniazid may sell his powerful red rifampin capsules to his friends (or the witch doctor) for use in the treatment of gonorrhea and then take only the isoniazid himself, resulting in isoniazid monotherapy! This man acquires isoniazid resistance, cough recurs, and ethambutol is added by a kindly physician, which effectively now constitutes ethambutol monotherapy. Soon, resistance to ethambutol emerges and the man's health continues to decline. Perhaps he will start taking his rifampin, which means he is receiving rifampin monotherapy.

Such patients first need to know that they must either take both medications and get better, or take neither and get worse, but at least, in this latter instance, the disease remains drug susceptible. It is always a mistake to add one drug at a time to a failing regimen. Instead, at least two new drugs should be added to protect against the emergence of resistance to each other. Fully supervised therapy prevents scenarios such as these from happening, but, unfortunately, at present it is not feasible on a global scale.

Case

A 73-year-old man is admitted because of a 3-month history of intermittent hemoptysis. Approximately once a week he has been coughing up small amounts of blood-streaked sputum, but, on the day before admission, he started to cough frequently and produced approximately half a cupful of red and clotted blood over a 24-hour period. The patient had emigrated to America in the 1940s after having been interned in a labor camp in Europe during World War II. A medical examination at the time of his liberation revealed he had tuberculosis. He was then admitted to a sanatorium, where he stayed for 18 months, with treatment consisting of artificial pneumothorax. In the 1950s, he had a relapse and was treated for 18 months with isoniazid, paraaminosalicylic acid, and streptomycin. He continued to smoke a pack of cigarettes per day until an attack of pneumonia 5 years before, which caused him to stop smoking. For the past year, he has been increasingly disabled by exertional dyspnea, such that he is now unable to climb a flight of stairs without stopping. He has also had recurrent exacerbations of breathlessness with productive cough, but no previous hemoptysis. He has recently noted increasing ankle edema. He has no history of weight loss or fever.

P.237

On examination, he is found to be thin and anxious, afebrile, and normotensive, with a regular pulse of 110 beats per minute. He is slightly tachypneic and has both central and peripheral cyanosis. The jugular venous pulse is visible approximately 3 cm above the clavicle when he is at an angle of 45 degrees. He has a discrete, firm, nontender lymph node that is enlarged to approximately 2 cm in the right supraclavicular fossa. The trachea is deviated to the right, and the right upper chest is noted to be indrawn below the clavicle; it is dull to percussion and bronchial breath sounds are heard. The apex of the heart is not palpable and auscultation of the heart reveals a loud pulmonary second sound. He has bilateral ankle edema.

The chest radiographic study on admission depicts bilateral, severe fibrotic lung disease, which is most marked in the upper lobes, with elevation of the hila; the abnormalities are more pronounced on the right. The horizontal fissure is elevated on the right and projects upward. Deviation of the trachea to the right is confirmed. There are thin-walled cavities bilaterally, and a cavity on the right is found to contain an opacity that is outlined by a crescent-shaped rim of air. A review of his laboratory records reveals that serum precipitins for aspergillus were found in his blood on a test sent from the outpatient department earlier in the month.

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

If massive hemoptysis supervenes, how should this be managed?

What is the most useful investigation to confirm the diagnosis?

Should the patient receive intravenous amphotericin B?

What additional late complication of tuberculosis does this patient exhibit, and how can this be relieved?

Case Discussion

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

Diagnoses that should be considered in this patient include aspergilloma, reactivation of the tuberculosis, carcinoma of the bronchus, and bronchiectasis. However, this patient exhibits the classic clinical picture of aspergilloma. Aspergillus colonizes and grows saprophytically in cavities created by preexisting lung disease (typically those caused by tuberculosis, although occasionally other diseases such as sarcoidosis, bronchiectasis, or pulmonary fibrosis can cause the formation of cavities hospitable to such infection). A fungus ball develops in the preexisting cavity, which is lined with bronchial epithelium or granulation tissue. Chest radiographic studies, tomograms, or computed tomographic (CT) scans can show the rounded opacity within the cavity, together with a crescent-shaped rim of air between the cavity and its wall. The ball may lie free within the cavity (in which case it can be seen to change position on decubitus chest radiographs) or it may be attached by granulation tissue. Often the patient is asymptomatic, but hemoptysis is the most important complication of aspergilloma. Serum precipitins to aspergillus are further supportive evidence for this diagnosis because these are found in 90% to 95% of cases of aspergilloma.

In this patient, reactivation of the tuberculosis is less likely than aspergilloma because, despite a 3-month history, the patient has not lost weight or had a fever. In

P.238

addition, the cavities seen on the chest radiographs have thin walls, suggesting the presence of inactive disease. However, radiologically, it is impossible to distinguish with certainty between active and inactive tuberculosis.Carcinoma of the bronchus might also be expected to cause weight loss, and it is an important consideration in patients with a history of tuberculosis because they are at higher risk than the general population because of the carcinoma (usually adenocarcinoma or alveolar cell carcinoma) that can form in scarred tissue, as an aftermath of infection. This patient is also at risk for bronchial carcinoma because of his long history of smoking.

Tuberculosis commonly leads to bronchiectasis, which would undoubtedly coexist in a patient like this who has severe destructive lung disease. However, this patient's episode is dominated by hemoptysis, rather than by the expectoration of copious, purulent sputum, which would be more suggestive of an exacerbation of bronchiectasis.

If massive hemoptysis supervenes, how should this be managed?

The major risk from aspergilloma is life-threatening hemoptysis. The prognosis for pulmonary aspergilloma is negatively influenced by a number of factors including the documentation of increasing size or numbers of the aspergillomas on chest radiographs, severe underlying lung disease, increasing Aspergillus-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, immunosuppression such as corticosteroids or HIV infection, and the presence of sarcoidosis. Surgical removal is the preferred treatment in the setting of life-threatening hemoptysis due to aspergilloma, although in this patient (as in many with aspergilloma), severe underlying lung disease indicates the likelihood of a poor outcome after pulmonary surgery. Embolization of the bronchial artery has been used successfully to control severe hemoptysis due to tuberculosis, among other causes, but has not been successful in the management of severe hemoptysis caused by aspergilloma, probably because of the large collateral circulation involved.

While arrangements are made for definitive management, a patient with severe hemoptysis should be positioned on the side of the suspected source (in this case, the right side) to minimize flooding of the unaffected lung with blood. Sedation of the patient is likely to be required. An intravenous line should be established and blood crossmatched and administered when needed.

What is the most useful investigation to confirm the diagnosis?

No investigation (other than pathologic analysis of the surgical specimen) is specific in confirming the diagnosis of aspergilloma, but Aspergillus precipitins are present in a high proportion of cases of aspergilloma and can serve to confirm the diagnosis in a patient with the characteristic clinical and radiologic presentation, such as that described here. Sputum culture for Aspergillus organisms is less helpful because it may yield no organisms if the cavity does not communicate with the bronchus. Skin tests with Aspergillus antigens are also less reliable.

Microscopic examination of the sputum for acid-alcohol fast bacilli should be done in a case such as this to exclude coexisting active tuberculosis, although, both clinically and radiologically, this is a less likely diagnosis. A reasonable precaution

P.239

would be to place the patient in respiratory isolation until negative smear results have been obtained.Should the patient receive intravenous amphotericin B?

There have been no prospective studies comparing the outcome in patients with aspergilloma treated with intravenous amphotericin B versus the outcome in untreated patients. The findings from retrospective studies suggest, however, that this treatment confers no beneficial effect, and this is not surprising, given that the fungal ball is isolated from the bloodstream. Asymptomatic patients may simply be monitored and resolution may occur spontaneously. Prophylactic surgical removal may be considered in patients who are fit for the procedure because of the potential of aspergilloma to cause fatal hemoptysis, and because surgery may effect a lasting cure. However, the poor exercise tolerance and the clinical findings indicating respiratory failure in this case suggest that the patient would be unlikely to tolerate the procedure. This could be confirmed by formal pulmonary function tests. Poor prognostic indicators would be an arterial blood gas analysis showing an elevated partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) and a forced expiratory volume of less than 1 L per second.

What additional late complication of tuberculosis does this patient exhibit, and how can this be relieved?

The patient has central cyanosis, indicating that he has hypoxia at rest. This is an additional late complication of pulmonary tuberculosis, probably exacerbated in his case by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to smoking. The hypoxia has resulted in pulmonary vasoconstriction and, hence, in pulmonary hypertension (indicated by the loud pulmonary second sound heard on auscultation of the heart). This, in turn, has resulted in right ventricular failure (indicated by the raised jugular venous pressure and edema), or cor pulmonale. Continuous administration of oxygen is indicated for relief of this syndrome.

Suggested Readings

Akbari JG, Varma PK, Neema PK, et al. Clinical profile and surgical outcome for pulmonary aspergilloma: a single center experience. Ann Thoracic Surg 2005;80:1067.

Glimp RA, Bayer AS. Pulmonary aspergilloma: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Arch Intern Med 1983;143:303.

Greene R. The radiological spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Med Mycol 2005;43(Suppl 1):S147.

Kauffman C. Quandary about treatment of aspergillomas persists. Lancet 1996;347:1640.

Kim YT, Kang MC, Sung SW, et al. Good long-term outcomes after surgical treatment of simple and complex pulmonary aspergilloma. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:294.

Mitchison DA. Basic mechanisms of chemotherapy. Chest 1979;76(6 Suppl):771.

Shapiro MJ, Albelda SM, Mayock RL, et al. Severe hemoptysis associated with pulmonary aspergilloma: percutaneous intracavitary treatment. Chest 1988;94:1225.

Stevens DA, Virginia L, Kan VL, et al. Practice guidelines for diseases caused by aspergillus. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:696.

P.240

Sepsis

Is there a clinical distinction between bacteremia and sepsis?

What is the distinction between chills and rigors?

What factors are associated with a poor prognosis in the setting of gram-negative sepsis?

Discussion

Is there a clinical distinction between bacteremia and sepsis?

It is important to differentiate among bacteremia, sepsis, and septic shock. Bacteremia is defined as the presence of viable bacteria in the blood, as demonstrated by a positive blood culture. Bacteremias may be further classified as transient, sustained, or intermittent, depending on the length of time blood cultures are positive. Transient bacteremias are common and last for only several minutes. When multiple blood cultures are positive over the course of several hours to several days, this indicates a sustained bacteremia. Intermittent bacteremias are those in which the blood cultures are intermittently positive. Sepsis is a clinical term that refers to a physiologic state that is associated with severe infection. In septic shock, there is hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or a one-third reduction from the prior systolic blood pressure) and evidence of end-organ damage secondary to reduced blood flow.

What is the distinction between chills and rigors?

It is very important to know the difference between chills and rigors. Rigor (a true shaking chill) is very often associated with bacteremia. The patient may experience teeth chattering and body tremors that usually last for 15 to 30 minutes. A chill is more appropriately described as a chilly sensation, not a clinical presentation. Rigors may be seen in the setting of viral infections as well as bacteremias.

What factors are associated with a poor prognosis in the setting of gram-negative sepsis?

Despite advances in supportive therapy, the mortality rate associated with gram-negative septic shock approaches 40%. Factors that contribute to this poor prognosis are increased age, poor nutritional status, steroid use, cirrhosis, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and granulocytopenia. Outcome is also adversely affected by volume depletion, inappropriate antibiotic use, and delay in therapy.

Case

A 74-year-old white man with Alzheimer's disease is brought to the emergency room by ambulance after a 1-day history of fever and mental status changes. On arrival in the emergency room, his blood pressure is found to be 100/60 mm Hg, heart rate is 100 beats per minute, temperature is 38.5 C (101.3 F), and respiratory rate is 24 per minute. The patient is unable to give any history; however, his wife states that he had been in his usual health until the evening before admission, when he began to complain of generalized abdominal pain and had become more confused than usual.

P.241

Physical examination reveals an agitated elderly man who is in no acute distress. His oral mucosa is dry and the lung examination reveals decreased breath sounds at the bases bilaterally. Cardiac examination reveals sinus tachycardia. Abdominal examination reveals normal bowel sounds and a palpable mass in the lower abdomen extending from 2 cm below the umbilicus down to the pelvis. Rectal examination reveals an enlarged, firm prostate, and the stool is heme negative. His extremities are cool and clammy and there is decreased skin turgor.

Admission laboratory results are as follows: white blood cell count, 16,000/mm3 with a differential count of 85% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 10% band forms, and 5% lymphocytes; hematocrit, 47%; creatinine, 2.3 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 40 mg/dL; sodium, 141 mEq/L; potassium, 4.5 mEq/L; chloride, 107 mEq/L; and carbon dioxide, 17 mEq/L. Arterial blood gas measurement performed on room air reveals a pH of 7.29, a PO2 of 68 mm Hg, and a PCO2 of 30 mm Hg. His chest radiographic findings are unremarkable. The patient is asked for a urine specimen but is able to void only 5 mL of cloudy, dark yellow urine, which is sent to the laboratory for urinalysis and culture.

A Foley catheter was subsequently placed and 500 mL of foul-smelling urine was obtained. A Gram's stain revealed numerous polymorphonuclear cells and gram-negative rods. On repeat examination, his abdomen was found to be soft and the mass had disappeared.

What system is the likely source of infection in this patient, and how could infection at this site explain his other signs and symptoms?

What group of organisms is most likely associated with the sepsis syndrome in this patient, and how does this group differ from the other major groups of bacteria and fungi?

How does endotoxin affect macrophages, and what chemical signals are produced by macrophages to contribute to the sepsis syndrome?

Of what should the initial management of a patient with the sepsis syndrome consist?

Case Discussion

What system is the likely source of infection in this patient, and how could infection at this site explain his other signs and symptoms?

The most likely diagnosis that fits with this patient's constellation of symptoms is urosepsis. As brought to light by the physical examination, the patient has the signs of septic shock impaired tissue perfusion, hypotension, and lactic acidosis in association with positive blood cultures. Tachycardia, tachypnea, and oliguria are also usually seen in the setting of genitourinary, gastrointestinal, biliary, and gynecologic infections, and therefore are not specific to urosepsis. Abnormalities in mental status may also be a feature of the initial presentation, even without infection in the CNS. In elderly patients, the symptoms of mental obtundation may be subtle and consist only of withdrawal or agitation, and they may constitute the sole indication of severe infection. The chest radiographic study in this patient was negative with no evidence of an infiltrate, making pneumonia unlikely. However, the clinician must always keep in mind that with hydration an infiltrate may blossom, so the patient's

P.242

respiratory status should be monitored closely. Because the mental status changes may be the only early manifestation of sepsis in the elderly, more often than not a lumbar puncture yields normal fluid. This patient's physical examination findings were also remarkable for an abdominal mass, and indeed he had complained of diffuse abdominal pain for at least 1 day before admission. Certainly, elderly patients may have appendicitis, diverticulitis with an abscess, or a colon carcinoma with subsequent bacteremia, and all these conditions must be included in the differential diagnosis. He was noted to have an enlarged prostate and also had difficulty voiding.What group of organisms is most likely associated with the sepsis syndrome in this patient, and how does this group differ from the other major groups of bacteria and fungi?

The organisms most frequently isolated in the blood of patients with the sepsis syndrome are gram-negative bacilli. Shock occurs less frequently in the setting of bacteremia due to gram-positive organisms. This difference may stem from variations in the host response to different bacterial cell wall constituents. The lipopolysaccharide portion of the cell wall of gram-negative bacilli (called endotoxin) elicits a vigorous inflammatory response when injected intravenously into animals. The inflammatory response to lipoteichoic acid, a cell wall constituent of gram-positive organisms, is much less pronounced. This patient had not been hospitalized, nor had he undergone any kind of instrumentation. Therefore, the most likely organism to cause a UTI with subsequent bacteremia and sepsis syndrome in this patient is E. coli. Other potential gram-negative organisms that may precipitate septic shock include Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Serratia marcescens. The primary portal of entry is the genitourinary tract, but the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, and skin are also important sources of bacteremia. Enterococcus must also be considered as a potential cause of this patient's illness because it can frequently cause prostatitis. Other gram-positive organisms, such as coagulase-positive and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, can certainly cause bacteremia and sepsis syndrome; however, this occurs most commonly in hospitalized patients who have had some type of intravascular device installed. Gram's stains are particularly useful in establishing presumptive diagnoses in UTIs, as it was in this case.

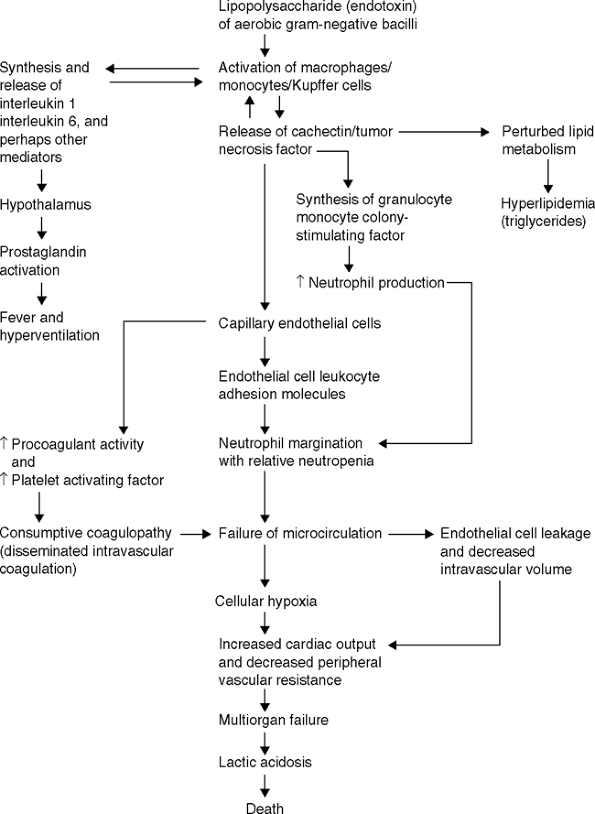

How does endotoxin affect macrophages, and what chemical signals are produced by macrophages to contribute to the sepsis syndrome?

Several bacterial factors are powerful mediators of sepsis, and one of the most potent is endotoxin. As stated, endotoxin is the lipopolysaccharide component of the cell wall in gram-negative bacteria. It appears that when cell injury occurs with the activation of immune defenses or the initiation of antimicrobial therapy, bacterial cell lysis takes place and the titer of detectable endotoxin in the patient's blood rises dramatically. Endotoxin binds to the CD14 molecule on the surface of macrophages that activate one of the members of the Toll-like receptor family (TLR-4). TLR-4 triggering activates a cascade of inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF- ) and a number of additional downstream mediators including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, IL-6, and platelet-activating factor. After the release of TNF- , IL-1, and platelet-activating factor, arachidonic acid is metabolized to form leukotrienes,

P.243

thromboxane A2, and prostaglandin E2. IL-1 and IL-6 activate T cells to produce interferon- , IL-2, IL-4, and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. The coagulation cascade and complement system are also activated (Fig. 6-1). Clinically, this phenomenon results in a low central venous or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, as well as a marked decrease in total systemic vascular resistance. In addition, there is a compensatory increase in cardiac output in an attempt to maintain arterial perfusion. The end result of this process is an increase in cardiac output, a marked fall in peripheral vascular resistance, and hypotension. If uncontrolled, progressive lactic acidosis ensues, ultimately leading to death.

Figure 6-1 Pathogenesis of the microvascular injury and death due to endotoxin shock. (From

Karchmer AW, Barza M, Drew WL, et al. Infectious disease medicine (MKSAP IX). Philadelphia: American College of Physicians, 1991

.)Of what should the initial management of a patient with the sepsis syndrome consist?

Although antibiotic therapy is the mainstay of treatment of sepsis caused by gram-negative organisms, the amelioration of underlying conditions, elimination of predisposing factors, drainage of abscesses, removal of infected foreign bodies, and adequate supportive care are also of paramount importance for curing the infection. It is critical to remember that the immediate therapeutic intervention should be directed at increasing cardiac output and oxygen delivery to prevent or minimize hypoperfusion and reduce tissue hypoxia. An optimal intravascular volume must be restored and maintained. Fluid requirements are very unpredictable because of capillary leak, and, at the very least, central venous pressures should be monitored so that these requirements can be appropriately met. Respiratory status and acid base disturbances can be observed with serial arterial blood gas measurements, which are also helpful in determining a patient's prognosis. The chance for survival is reduced in patients who are acidemic. The next step is to obtain appropriate cultures and administer appropriate bactericidal agents. The antibiotic regimen should be chosen on the basis of the presumed source of the bacteria and the susceptibility pattern of organisms from that source. Antimicrobial therapy should be adjusted on the basis of microbiologic data as they become available. Additional therapies that are under investigation are based on the emerging knowledge of the pathophysiologic sequence of bacteremic shock. The conduct and interpretation of many of these studies have been complicated by a lack of precision of entry criteria that make the extrapolation of study results to clinical practice, difficult.

Suggested Readings

Abraham E, Laterre PF, Garg R, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1332.

Abraham E, Reinhart K, Opal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tifacogin (recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor) in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:238.

Cross AS, Opal SM. A new paradigm for the treatment of sepsis: is it time to consider combination therapy? Ann Intern Med 2003;138:502.

Munford RE. Sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and practices of infectious diseases, 6th ed. New York: Elsevier Science, 2005:906.

Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Ward PA. Novel strategies for the treatment of sepsis. Nat Med 2003;9:517.

P.244

P.245

Sands KE, Bates DW, Lanken PN, et al. Epidemiology of sepsis syndrome in 8 academic medical centers. JAMA 1997;278:234.

Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll like receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 2003;21:335.

Endocarditis

What types of organisms can cause infective endocarditis?

What are some important factors that increase the risk for the development of endocarditis?

What are the two clinical types of bacterial endocarditis and their clinical characteristics?

What conditions call for surgical intervention?

Are there any differences in the characteristics of endocarditis between the intravenous drug abuse population and non drug abusers?

Discussion

What types of organisms can cause infective endocarditis?

There are many organisms that can infect the heart and cause endocarditis. The most common ones are traditional bacteria, but other organisms including fungi, Rickettsia, and Chlamydia may invade myocardial tissues and produce disease.

What are some important factors that increase the risk for the development of endocarditis?

The two major classes of risk factors contributing to the development of endocarditis include structural damage to cardiac tissue in contact with blood and conditions associated with bacteremia. Underlying heart diseases such as rheumatic valvular damage, a bicuspid aortic valve, patent ductus arteriosus, and small ventricular septal defects cause damaged tissue or abnormal blood flow, conditions under which bacteria can adhere to the surface and cause infection. Also implicated for the same reasons are prosthetic valves. Intravenous drug abusers are at risk for endocarditis because their valves are being constantly bombarded with impurities such as talc, which causes scarring of the valves, and also because they mix their drug of choice with contaminated water. Nosocomial infections may result from the placement of intravenous catheters or pacemaker wires, or from wound infections or genitourinary manipulation. Elderly patients are also at increased risk for endocarditis.

What are the two clinical types of bacterial endocarditis and their clinical characteristics?

Although there is overlap, the two clinical types of bacterial endocarditis are acute and subacute. Acute bacterial endocarditis is most commonly associated with intravenous drug abuse, intravenous catheter infection, and prosthetic valve infections. These infections may be rapidly fatal if left untreated, and surgical repair or replacement of the damaged valve may be necessary. Subacute

P.246

endocarditis develops most often in the setting of structural heart disease (e.g., mitral valve prolapse), a history of rheumatic heart disease, or prosthetic valves. It also affects elderly patients, or it may occur in the setting of no known valvular disease. Its onset tends to be more indolent. Symptoms such as weakness, fatigue, night sweats, and weight loss may have existed for weeks to months before diagnosis. Its onset may be related to antecedent events such as dental work, although no definite predisposing event is apparent in most cases. Because some patients may have multiple risk factors and exhibit a variable clinical picture, their disease cannot be easily classified. It is always important to keep in mind the maxim that if you don't think about endocarditis, you won't diagnose it!What conditions call for surgical intervention?

Surgical intervention should be considered if (a) there is more than one embolic event; (b) bacteremia persists despite 2 to 3 weeks of adequate antibiotic therapy; (c) there is progressive or refractory congestive heart failure; (d) there is significant valvular dysfunction resulting in moderate to severe congestive heart failure as demonstrated by echocardiography or other laboratory techniques; (e) local suppurative complications arise, as reflected by the appearance of new, persistent electrocardiographic conduction disturbances, echocardiographic evidence of a paravalvular abscess or fistula, purulent pericarditis, or persistent unexplained fever despite appropriate antibiotic therapy; (f) there is fungal endocarditis; or (g) there is appropriately treated prosthetic valve endocarditis due to drug-resistant organisms that recur despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

Are there any differences in the characteristics of endocarditis between the intravenous drug abuse population and nonaddict population?