Games Governments Play with the Pharmaceutical Industry

The only player who can do more harm to a company than an incompetent management team is a confiscating government. Would you be willing to work long hours generating wealth if the government was just going to expropriate the fruits of your labor? Governments have varying degrees of capacity to seize the wealth of companies. The high sunk costs of the pharmaceutical industry make it especially vulnerable to governmental takings.

Governments sometimes force companies to cut prices in shallow attempts to placate voters. The marketplace normally puts a reasonable limit on the government’s ability to mandate low prices. For example, imagine that it costs companies $100 to make a widget that they sell for $110. If the government forces widget makers to sell their product for only $50, disaster would result because the widget makers would go bankrupt. Politicians receive no political payoff from mandating suicide prices.

Now imagine, however, that a widget that sells for $110 costs only $1 to manufacture. If the government forced widget makers to sell their product for $50, the companies would comply and the politicians would become more popular for having lowered consumer prices.

Pharmaceutical products are often sold at prices far above manufacturing costs because of the high sunk costs associated with the pharmaceutical industry. It costs millions to make the first copy of a drug but sometimes only pennies to make the second. Massive sunk costs permit the government to impose low prices on pharmaceutical companies. To understand this, assume that

$99 million = the cost to design the drug or make the first copy.

$1 = the cost of making the second and subsequent copies of the drug.

1 million = the total number of people who want to buy the drug.

If the pharmaceutical company sells one million of these drugs, its costs will be the $99 million sunk costs to make the first copy plus the $1 million variable costs to manufacture a million copies, so the total cost of producing 1 million copies of this drug is $100 million, or on average, $100 per drug. Let’s imagine that this company charges a price of $110, but the government complains, claiming that since the company pays only $1 to make each new drug, it’s unfair to charge $110. What if the government told the pharmaceutical company that it could charge no more than $50 a unit? Since the drug costs the pharmaceutical company on average $100 a unit, should they be willing to sell their product for merely $50? Yes, because of the drug’s high sunk costs. If the pharmaceutical company sells one more drug for $50, it obviously gets an additional $50 but only pays an extra $1 in manufacturing costs. Therefore, once the pharmaceutical company has incurred the $99 million sunk cost, it is better off selling a drug so long as it gets more than $1 for it.

It takes more than a decade to develop and test a new drug. Consequently, pharmaceutical companies must try to predict what future restrictions on price the government will impose. Governments have strong political incentives to limit pharmaceutical prices. When the government lowers drug prices it reduces research and development for not-yet-developed drugs but lowers prices for today’s consumers. The benefits of price restrictions are felt immediately, while the cost, which is a reduced number of future drugs, takes at least a decade to manifest itself.

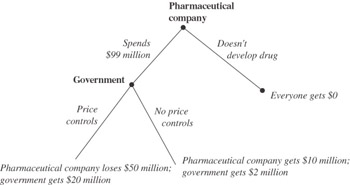

The pharmaceutical companies fear they are playing a game like Figure 8. In this game the pharmaceutical company first decides whether to incur the sunk costs to develop the new drug. If they make the investment, the government decides whether to impose price controls. The game assumes that the government cares mostly about the present and so benefits from imposing price controls on developed drugs. Of course, if the company knows that the government will impose price controls, it won’t develop the product; this would be the worst case for the government. The government would benefit from credibly promising not to impose price controls. Pharmaceutical companies would probably not believe such a promise, however, because of the political payoffs politicians receive from lowering drug prices. The only solution to this credibility problem is for the government to develop a long-term perspective and genuinely come to believe that the damage done by price controls exceeds their short-term political benefits.

Figure 8

Many AIDS activists seem ignorant of pharmaceutical economics. AIDS activists continually pressure pharmaceutical companies to lower prices. They also argue that the low cost of making additional copies of AIDS drugs means that pharmaceutical companies should give their drugs away for free to poor countries. Tragically, the AIDS activists’ complaints signal that if someone ever does find a cure for AIDS, then the activists will do their best to ensure that the cure is sold for a very low price. The activists are effectively promising to reduce the future profits of anyone who finds a cure or vaccine for AIDS. Indeed, I predict that if a for-profit organization does find a cure or vaccine for AIDS, then AIDS activists will loudly condemn this organization for not selling the wonder treatment at a lower cost. Obviously, the pharmaceutical companies take these potential profit objections into account when deciding how much to spend on AIDS research.

EAN: N/A

Pages: 260