Business Process Management

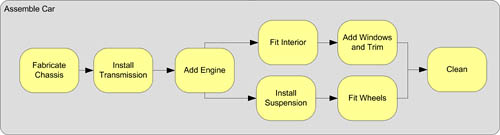

| The model of a business as the sum of its processes is a useful abstraction from which to begin understanding a business. For example, a supermarket is the summation of processes that buy and sell produce and a handful of other processes that keep the shop running. Similarly, but on a grander scale, an airline consists of processes for flight sales, plane maintenance, and so on right down to the processes that ensure that passengers receive meals on board the aircraft. A classic example of a business process (which has the added advantage of being both familiar and ostensibly linear since it is based on a production-line pattern) is the manufacturing of motor vehicles being one of the processes that a typical motor manufacturer will engage in as part of its business. Let us consider a typical, though somewhat simplified, view of manufacturing a family car, as shown in Figure 6-1. Figure 6-1. A motor vehicle construction business process.

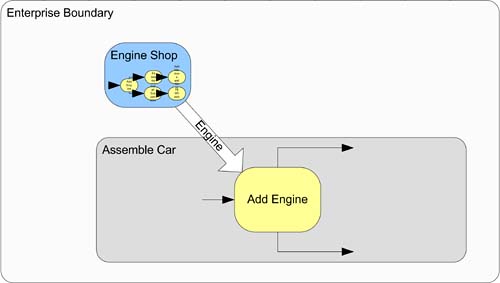

The business process shown in Figure 6-1 is perhaps typical of many real-world processes where there are dependencies between some tasks (e.g., the installation of the transmissions system is predicated on the chassis being fabricated) that imply serialized execution, and parts of the system where there are no such interdependencies (e.g., on a sophisticated production line, the installation of suspension and wheels can proceed independently of the installation of seats and windows) where parallel execution can occur. Additionally, as the "Assemble Car" process is divided into its constituent subprocesses, those subprocesses themselves can be split, and so on, until a suitably grained process is arrived at. In a traditional enterprise, most of the activities are performed in-house. For example, it used to be the case that vehicle manufacturers would build for themselves every important component of their vehicles from the gearbox through to the engine and everything in between. For example, the "add engine" process from Figure 6-1 obviously depends on the engine shop in our business being able to produce engines to install. If we examine that aspect of the business process in more detail, we see that a pattern like that shown in Figure 6-2 emerges. Figure 6-2. Add engine process dependencies.

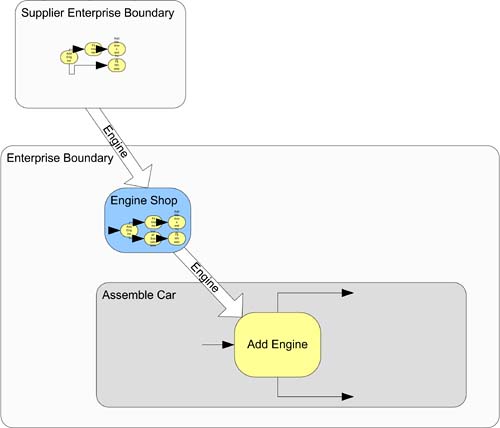

While this might seem like an eminently sensible arrangement at first (especially since it decouples the internals of building engines from the internals of assembling cars), some thought reveals that in fact it hampers business agility since any change in this practice has to be capitalized up front. For instance, consider the situation where our traditional business has decided to offer a range of hybrid hydrogen fuel cell/gasoline-based cars. Under normal circumstances our business would need to find the capital and expertise to begin to produce its new engine configurations in-house, which is an expensive and labor-intensive process. However, let us assume for argument's sake that there exist other companies whose own core competencies are not in building cars, but in building hybrid engines for cars. Given the fact that our vehicle assembly and engine construction processes are decoupled, it should be possible to simply source the new engines from a third-party supplier rather than from our own in-house stock (provided the two types of engine are, of course, physically compatible). This leads to a situation shown in Figure 6-3 where the processes of our suppliers are linked into those of the vehicle manufacturer to form a "virtual enterprise." In this arrangement, the ultimate source of the engine for a particular vehicle can either be in-house or third-party, depending on the requirements of that vehicle, without upsetting the vehicle assembly process and thus allowing the company to continue to manufacture cars and add value. Of course some of the processes within the "engine shop" may need to change a little to accommodate purchasing of complete engines (as opposed to previously purchasing raw materials or simple components) but, as a whole, the changes to the overall process are relatively confined in scope to the engine shop's systems and are (hopefully) painless. Figure 6-3. The virtual enterprise.

A virtual enterprise consists of both a business's own processes, as well as those of its partners, suppliers, and customers as single system. Taking such a holistic view generally allows the whole system to function seamlessly from a business perspective (though as we shall come to appreciate this does present certain technical challenges from a software point of view). The kinds of changes made to business processes characterized in Figure 6-3 and the ability to manage change within those processes are the hallmark of an agile business. It is a simple truth that businesses with good processes succeed while those with poor processes fail, and that high-quality processes only remain as long as they are able to change rapidly in response to market conditions. The use of computerized business process management systems is attractive because it supports the notion of rapidly evolvable business processes based on a powerful and flexible IT infrastructure. Such systems are known as Workflow Management Systems and it is these systems that take the abstractly defined business process and turn it into a computer-coordinated reality. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 141