Interpreting a Foreign Language

The main difference between interpreting perception and interpreting a foreign language is that in the latter case you are actually reinterpreting something that has already been interpreted. In other words, it is not raw sensation, but someone else's perception, predigested and presented as language.

The interesting corollary to this is that it is obvious that you need to interpret a foreign language. It is evident that someone is trying to communicate with you, and you will need to do something if you hope to understand the person. Looking at a painting, after you interpret that it is a painting you may feel no need to interpret further, until someone points out that it is titled "Nude Descending a Staircase," at which point you are prodded to do some more interpretation.

How Does Translation Work?

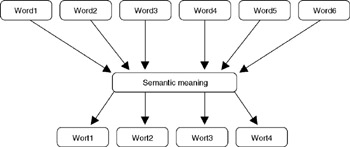

The simplistic view of translation is that it works something like the illustration in Figure 7.2. Each word in the source language has an equivalent word in the target language and it is just a matter of looking them up and making the substitution. The existence of language-language dictionaries (French-English, English-German, etc.) implies that this is a useful strategy.

Figure 7.2: Na ve assumption about translation ("wort" is German for "word").

However, this strategy is useful only to a point. For example, it works for specific nouns, such as if we want to know the German word for "tiger." However, most word-for-word translations miss the contextual meaning and require some level of semantic interpretation.

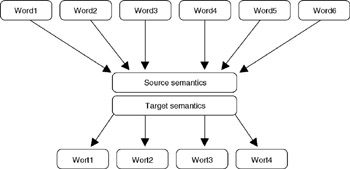

Language translation is closer to what is shown in Figure 7.3. A person (or potentially a program) interprets and understands a series of words. If the person (or program) has a sufficiently expressive vocabulary and grammar, he or she (or it) can express the concepts in another language.

Figure 7.3: Translation as words to meaning to words.

In the process of translating from one language to another, does the human translator create a semantic version of the thought in his or her source language? From that, does the translator construct a semantic version in the target language, and then map that to the target language vocabulary (as shown in Figure 7.4)? Or is there just one semantic version, as in Figure 7.3? In other words, are our deep semantics expressed in a spoken language, and if so is it our native language? Or are they expressed in some other fashion?

Figure 7.4: Semantics in two languages.

The question for business systems is, Are we stuck with translating one schema to another for any possible pair of schemas, or is there an intermediary to which all schemas will reduce, without losing meaning? The answer to this question is unknown.

Some anthropologists believe that certain thoughts are not expressible in other languages or cultures. Sometimes a culture doesn't have a word, but once it gets the concept it creates a word. The German word schadenfreude means "taking delight in the misfortune of others." English doesn't have a word for this. But clearly this is a concept we understand, and we now have the choice of expressing it as a phrase or adopting the German word into our vocabulary (which seems to be happening at a rapid rate). This line of reasoning seems to lead to a language-specific set of semantics.

The fact that, with translation, we can understand each other, and that people raised in one culture can learn another language and culture, leads me to believe that all humans share a common semantic model. I may have 40 fewer distinctions for snow than an Inuit does, but I don't think I'd have to be brought up Inuit to acquire the Inuit distinctions. There are probably a small number of concepts that have an experiential basis and that therefore have words that are not translatable, but from my experience and research these seem to be more the exception than the rule.

Work by linguistic scholars suggests that out of a large number of possible grammars, only a few are used. This gives us a few semantic templates onto which we insert a few hundred thousand verbs, nouns, adjectives, and so on, and we have all possible semantic thoughts. Indeed, a vocabulary is just a flat representation of a few deeply nested and intertwined trees of generalization and specialization.

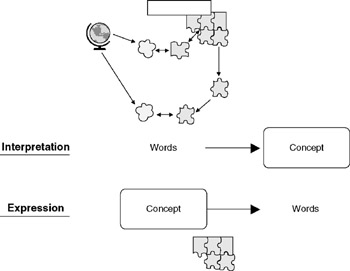

Interpretation is far harder than expression, as hinted at by Figure 7.5. Once we have the concepts, all we need for automated expression is a small knowledge base about the domain and vocabulary. Interpretation, on the other hand, involves context, interactive involvement with the environment, and potentially a much larger knowledge set.

Figure 7.5: Expression is far easier than interpretation.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 184