| Visual Studio is by far the most popular tool for creating .NET applications today. The current version, Visual Studio 2005, is the successor to Visual Studio .NET, which was itself the first version of this tool to support creating managed code. Both tools provide a very large set of services for developers, including all of the bells and whistles of a modern IDE. | Most .NET developers today use Visual Studio |

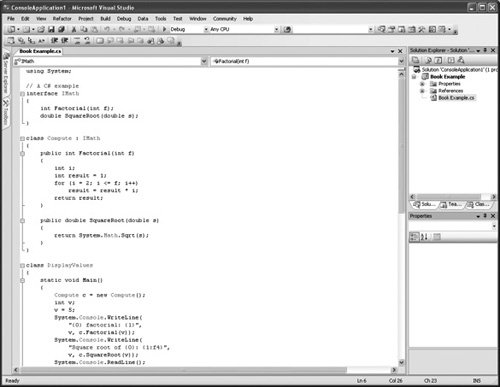

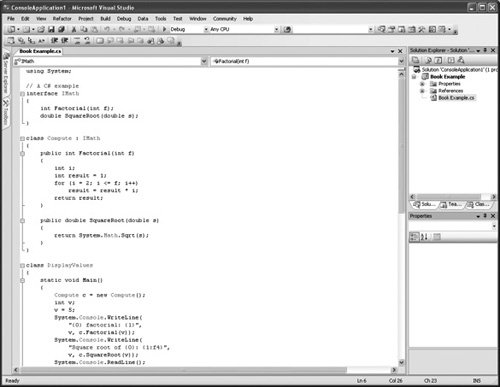

Figure 1-8 shows how Visual Studio looks to the creator of a simple .NET Framework application. Different windows show different aspects of the project, including the code itself and, in the lower right corner, any properties that may have been set. If you've never used a modern software development tool, don't be fooled by this very basic picture: Visual Studio is actually a complex and powerful IDE, one that's used by millions of developers today. Figure 1-8. Visual Studio provides a range of support for creators of .NET applications.

| Visual Studio is a family of products |

Visual Studio 2005 is actually a family of products, each aimed at a particular kind of developer. This family includes Visual Studio 2005 Express Edition, aimed at beginning developers and hobbyists, Visual Studio Standard Edition, aimed at more serious developers, and Visual Studio 2005 Professional Edition, intended for hard-core software professionals building scalable distributed applications. The product family also includes Visual Studio Tools for Office, which provides the ability to create applications in VB or C# that build on Excel, Word, Outlook, and InfoPath. Another important member of this family, one that's described in a bit more detail later in this chapter, is Visual Studio Team System, which provides a set of interrelated tools specialized for various roles in a development group. What's New in Visual Studio 2005 The introduction of Visual Studio Team System and support for DSLs are probably the two biggest innovations in Visual Studio 2005. This new version of Microsoft's flagship development tool also adds several other interesting new features, including the following: Refactoring support: Refactoring allows making small modifications to software that together can lead to significant improvement. Some common refactoring changes, such as extracting code and wrapping it in its own method, or encapsulating a field inside get and set methods, can be done through a built-in Visual Studio menu. Edit and continue: In pre-.NET versions of Visual Basic, a developer could change code in a running application while it was being debugged, then continue execution from the point of the change. Known as Edit and Continue, plenty of people found this useful. Omitted from Visual Studio .NET (to the great concern of some), this feature is now available with all of the programming languages supported by Visual Studio 2005. Code snippets: Many applications include code that performs common tasks. To make implementing these easier, Visual Studio 2005 provides snippets of prewritten code for common situations. Snippets are provided for declaring standard types, such as classes, creating common constructions, such as an if statement, and other typical programming tasks. Developers can also create new snippets then store them for future use.

|

As already described, several different programming languages can be used to create .NET Framework applications. Visual Studio 2005 ships with support for C#, VB, C++, and other languages, giving developers a range of choices. The 2005 version of the tool also adds support for using domain-specific languages (DSLs), an idea that's described later in this chapter. The main focus of Visual Studio, however, is helping developers create applications using general purpose CLR-based programming languages, and so the next section takes a brief look at this area. | Visual Studio 2005 provides a variety of different languages |

Perspective: The Fate of Pre-.NET Applications Applications built using the Windows DNA technologies that preceded .NET, such as COM and Visual Basic 6 (VB6), won't generally run on the .NET Framework without at least some modification. This is a problem for the many organizations that have invested in these applications. But just how big a problem is it? The answer depends on what kind of application we're talking about and what kind of organization is responsible for it. For example, think about a VB6 application built by a typical enterprise that solves a specific business problem. Installing the .NET Framework on the same machine that runs this app won't break the application, and since these older apps will happily run on newer versions of Windows, there's no requirement to change. If the application still meets the business need effectively, why invest the time and resources to rewrite it using .NET? True, the rewritten app would likely be better in some technical ways, but the benefits to its usersthe people who ultimately pay for itaren't likely to be large enough to justify the cost. But suppose this VB6 application needs to be modified in some way. It's always possible to just keep on using an older version of Visual Studio, one that (unlike Visual Studio 2005) supports VB6. But Microsoft's support for these older development environments is fading away, and many organizations feel uncomfortable relying on unsupported tools. In this case, the application may need to be rewritten solely to avoid this fate. What about applications written by independent software vendors (ISV)? For example, many ISVs (including Microsoft) have a large investment in applications written using pre-.NET versions of C++. Visual Studio 2005 allows working directly with raw C++you don't have to use the CLRand so there's no immediate need to change these applications. New Windows features are typically exposed via managed code, however, and so taking advantage of this new functionality will require extending the application with some CLR-based C++. Perhaps the hardest problem is that faced by ISVs or enterprises with a substantial investment in a VB6 application that still has many years of use ahead of it. An application like this is likely to need substantial change over time, yet creating new functionality in VB6 means freezing ever more work into a legacy technology. One option is to create new code in the .NET version of VB, then connect these additions to what already exists. To make this possible, the CLR has built-in support that allows managed code to call existing DLLs, access and be accessed by COM objects, and interoperate in other ways with the previous generation of Windows software. The big challenge here is the problem just mentioned: Versions of Visual Studio that support VB6 are falling out of support (although the VB runtime itself is still supported). In this case, it might be worth the investment to rebuild the entire application on .NET, especially if significant new functionality can be added at the same time. Yet another challenge of transitioning to a wholly new development environment is the cost of retraining developers. In the long run, avoiding the .NET Framework isn't possible for Windows-oriented organizations, so ponying up the cash for developer education is unavoidable. It's not cheap, and time will be lost as developers come up to speed on this new technology. The .NET Framework really is substantially better than its predecessors, however, so most organizations are likely to see productivity gains once developers have internalized this new environment. |

General Purpose Languages | Visual Studio 2005 supports CLR-based languages |

Although Visual Studio supports many different programming languages, the CLR defines the core semantics for most of them. Yet while the way those languages behave often has a good deal in common, a developer can still choose the language that feels most natural to her. All of these languages use at least some of the services provided by the CLR, and some expose virtually everything the CLR has to offer. Also, with the exception of C++, it's not possible to create traditional standalone binary executables in these languages. Instead, every application is compiled into MSIL and so requires the .NET Framework to execute. This section provides a short introduction to each of the most commonly used general purpose languages built on the CLR. C# The two dominant languages for Windows development in the pre-.NET world were C++ and Visual Basic 6 (VB6). Both had sizable user populations (although VB6's user base was much larger), and so Microsoft needed to find a way to make both groups as happy as possible with their new environment. How, for example, could the large number of Windows developers who know (and love) C++ be brought forward to use the .NET Framework? One answer is to extend C++, an option described later. Another approach, one that has proven more appealing for most C++ developers, is to create a new language based on the CLR but with a syntax derived from C++. This is exactly what Microsoft did in creating C#. | C# is the natural language for .NET Framework developers who prefer a C-based syntax |

C# looks familiar to anyone accustomed to programming in C++ or Java. Like those languages (and like the .NET version of VB), C# is object-oriented. Among the more interesting aspects of C# are the following: Support for implementation inheritance, allowing a new child class to inherit code from one parent class, sometimes referred to as single inheritance The ability for a child class to override one or more methods in its parent Support for exception handling Full multithreading (using the .NET Framework class library) The ability to define interfaces directly in C# Support for properties and events Support for attributes, allowing features such as transaction support and Web services to be implemented by inserting keywords in source code Garbage collection, freeing developers from the need to destroy explicitly objects they have created Support for generic types, a concept similar to templates in C++ The ability to write code that directly accesses specific memory addresses, sometimes referred to as unsafe code

C++ or Java developers, who are accustomed to a C-like syntax, usually prefer C# for writing .NET Framework applications. VB6 developers, however, fond of their own style of syntax, often prefer the .NET version of VB, described next. Visual Basic From its humble beginnings at Dartmouth College in the 1960s, Basic has grown into one of the most widely used programming languages in the world today. This success was due largely to the popularity of Microsoft's Visual Basic. Yet it's likely that the original creators of Basic wouldn't recognize their child in its current form. The price of success has been adaptationsometimes radicalto new requirements. | Visual Basic is a very widely used language |

VB.NET, the first CLR-based version of this language, was a huge step in Microsoft's evolution of VB. In addition to being enormously different from the original Basic language, it was a big leap from its immediate predecessor, VB6. The primary reason for this substantial change was that VB.NET was built entirely on the CLR. The version in Visual Studio 2005, officially known as Visual Basic 2005, brings a few changes to the original VB.NET. On the whole, however, this version of the language is very much like the VB.NET incarnation that preceded it. | VB.NET was a big change from VB6 |

VB 2005 is much like C#, which shouldn't be surprising. Both are built on the CLR, and both expose the same core functionality. The biggest difference between C# and VB today is in syntax; functionally, the two languages are very similar. In fact, the list of interesting features in VB mirrors C#'s list: Support for single implementation inheritance Method overriding Support for exception handling Full multithreading (using the .NET Framework class library) The ability to define interfaces directly in VB Support for properties and events Support for attributes Garbage collection Support for generic types

| Visual Basic 2005 provides almost exactly the same features as C# |

Unlike its sibling C#, VB doesn't allow creating unsafe code. The 2005 version of VB does, however, provide an addition called the My namespace, making it easier to perform some common operations. Despite these differences, it's important to realize how similar VB and C# really are. The old division between C++ and VB6, two radically different languages targeting quite different developer populations, is gone. In its place is the sleek consistency of two closely related CLR-based languages: VB and C#. C++ C++ presented a challenge to the creators of .NET. To be able to build .NET Framework applications, this popular language had to be modified to use the CLR. Yet some of the core semantics of C++, which allows things such as a child class inheriting directly from multiple parents (known as multiple inheritance), conflict with those of the CLR. And since C++ plays an important role as the dominant language for creating non-Framework-based Windows applications, modifying it to be purely Framework specific wasn't the right approach. What's the solution? | The semantics of C++ differ from those defined by the CLR |

Microsoft's answer is to support standard C++ as always, leaving this powerful language able to create efficient processor-specific binaries as before. To allow the use of C++ to create .NET Framework applications, Microsoft added a set of extensions to the language. The C++ dialect provided with Visual Studio 2005 that includes these extensions is called C++/CLI, and it provides access to all features of the CLR. Using C++/CLI, a developer can write C++ code that takes advantage of garbage collection, defines interfaces, uses attributes, and more. | .NET Framework applications can be created using C++/CLI |

Because not all applications will use the .NET Framework, Visual Studio still allows building traditional Windows applications in C++. Rather than using C++/CLI, a developer can write standard C++ code and then compile it into processor-specific binaries. Unlike VB and C#, C++ is not required to compile into MSIL. | Standard C++ can also be used to create non-Framework-based applications |

Other CLR-Based Languages | Visual Studio 2005 also supports JScript .NET and J# |

It's fair to say that the great majority of .NET development is done in C#, VB .NET, and C++. Still, Visual Studio 2005 also supports two other CLR-based languages that are worth mentioning: JScript: JScript is based on ECMAScript, the current standard version of the language originally christened as JavaScript. As such, JScript provides developers with a loosely typed development environment, support for regular expressions, and other aspects typical of the JavaScript language family. Yet because it's based on the CLR, the .NET version of JScript also implements CLR-style classes, which can contain methods, implement interfaces, and more. While JScript can be used for creating essentially any .NET application, the language is most commonly applied in building ASP.NET pages. J#: Microsoft's implementation of the Java programming language, J# provides Java's syntax on top of the CLR. Don't be confusedJ# isn't intended for creating applications that run on a standard Java virtual machine. Microsoft also doesn't support many of the major Java libraries, such as Enterprise JavaBeans (EJB). Instead, J# provides a way to more easily transition Java developers and existing Java code to the world of .NET.

Microsoft also makes available a CLR-based version of the increasingly popular Python language. While it's not an integral part of Visual Studio, this implementation does allow access to the .NET Framework class library. It also demonstrates the ability of the CLR to support a broader range of programming languages, since Python is a dynamic language. Dynamic languages allow more change at runtime than more conventional approaches such as C# and VB, including things such as introducing new data types. To provide this kind of flexibility, the CLR-based version of Python relies on an interpreter rather than just a compiler. | Microsoft provides Python for the CLR |

Other vendors also provide tools and languages for creating .NET Framework applications. The most popular of these is probably Borland's Delphi. Widely admired as a language, Delphi has a hard-core user base around the world. The current version of this language is based on the CLR, and so it allows Delphi developers access to the services provided by the .NET Framework. | Other vendors, such as Borland, provide CLR-based languages |

Support for multiple programming languages is one of the most interesting things about the .NET Framework. Chapter 3 takes a closer look at C#, VB, and C++/CLI, the three most popular languages for building .NET Framework applications. Domain Specific Languages General purpose programming languages such as C# and VB are the mainstays of modern development. Yet the idea of model-driven development (MDD), where software creation depends at least in part on some kind of underlying abstract model, is a hot idea in the industry today. Visual Studio 2005 reflects this in its support for what are known as domain specific languages (DSLs). In general, a DSL might be expressed in text, graphically, or in some other way. For example, SQL can be thought of as a DSL designed for working with relational databases, while the graphical Orchestration Designer in Microsoft's BizTalk Server can be viewed as a DSL for defining some kinds of business logic. However it's defined, each DSL implements a set of higher-level abstractions for solving problems in a particular area. | Domain specific languages can help in moving toward model-driven development |

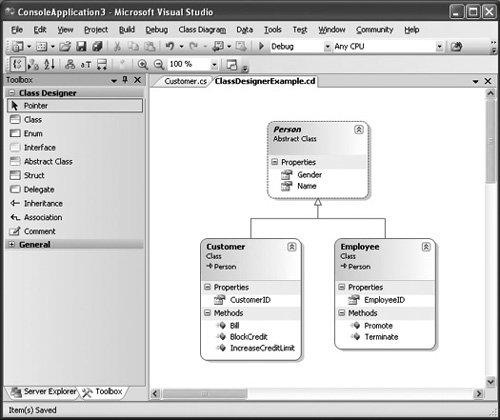

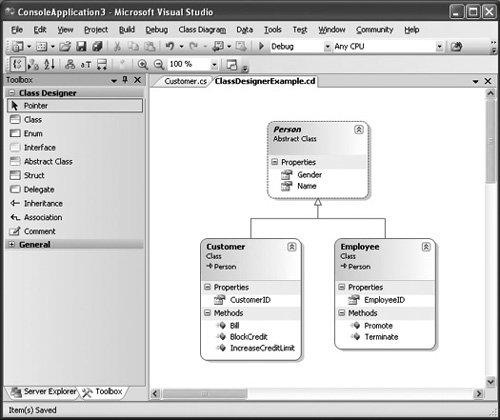

Visual Studio 2005 supports several graphical DSLs. Each is implemented in a specific graphical tool that focuses on a particular problem domain. For example, every version of Visual Studio 2005, except the Express Editions, includes a tool called the Class Designer. As Figure 1-9 illustrates, this tool provides a graphical DSL for creating and modifying classes and class hierarchies. Figure 1-9. The Visual Studio 2005 Class Designer provides a DSL for defining classes and class hierarchies.

| Visual Studio 2005 provides a Class Designer and other DSLs |

| The Class Designer DSL generates code from class diagrams |

The Class Designer allows a developer to create a new class by dragging and dropping an icon from the toolbox (shown on the left in Figure 1-9) onto the design surface. Properties, methods, and other aspects of the class can also be added graphically. This is more than just a tool for drawing pictures, however. The Class Designer actually generates code that reflects the defined classes. Changes to the diagram are reflected in the code, and changes made directly to the code are also reflected in the diagram. Especially for more complex scenarios, the ability to visualize classes and their relationships can be a big help in writing good code. Perspective: Microsoft's Approach to Model-Driven Development The dream of creating software through pictures has been with us for decades. Yet especially when they're expressed graphically, it's easy to look at DSLs and be reminded of the failure of computer-aided software engineering (CASE). Now that memories of the CASE debacle are fading, are DSLs just a repeat of this idea being foisted on a new generation? Maybeit's too soon to know. But increased developer productivity is a laudable goal, one that's worth taking some risks to achieve. The CASE technologies of the 1980s were far broader in scope than the relatively simple DSLs that are included in Visual Studio 2005. By avoiding the grand ambition of these earlier tools, Microsoft lessens the risk that its DSL efforts will meet the same fate. And the idea of creating at least some code graphically, especially code that targets a particular domain, is very attractive. Microsoft is taking a small step in the DSL direction with Visual Studio 2005. The company's stated goal is to make developers perceive that modeling has value, not to move to a completely model-based development environment. Given this, starting small seems wise. Building this approach into one of the world's most widely used developer tools will certainly provide a solid test of the idea. Microsoft isn't alone in promoting MDD, however. The Object Management Group (OMG), a multivendor consortium, has created a set of specifications for MDD. These specs define the OMG's Model Driven Architecture (MDA), and they have been endorsed by a number of vendors and user organizations. Yet Microsoft has essentially ignored MDA, choosing instead to go its own way. Microsoft and the OMG have never had an especially cordial relationship. OMG's first creation was the Common Object Request Broker Architecture (CORBA), a direct competitor to Microsoft's DCOM. Like CORBA, MDA takes an explicitly cross-platform, vendor-neutral approach. In fact, a primary MDA goal is to create models that can be implemented equally well using different technologies, such as .NET and Java. Given its diverse membership, it's not surprising that OMG starts from this perspective. It's also not surprising that Microsoft doesn't see the value in this. Visual Studio is a tool for building Windows applications, so why complicate things by implementing an MDD approach that strives to be cross-platform? And if you're Microsoft, what value is there in working with a committee of others to define what will ultimately be a Windows technology? Unsurprisingly, Microsoft continues to believe that for Windows programming interfaces, it should be in the driver's seat. Also, like the products of many standards committees, MDA is abstract and complex. (A friend of mine who's spent a considerable amount of time in the MDA world has described it as "where the rubber meets the sky.") While ignoring MDA might make Visual Studio integration with non-Microsoft tools more challenging, Microsoft's resistance to a technology created by its competitors is entirely in line with its usual perspective on the world. And as always, competition among different approaches is likely to make this technology improve more quickly. |

Working in Groups: Visual Studio Team System Like any development tool, the goal of Visual Studio is to help developers be more effective. Yet the majority of software today, and virtually all enterprise software, isn't created by a single individual. Software development has become a team sport, complete with specialized positions for various players. | Most software today is created by groups, not individuals |

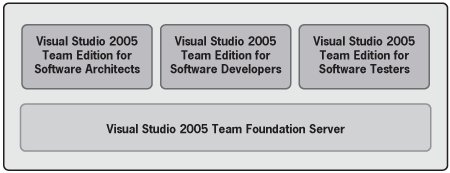

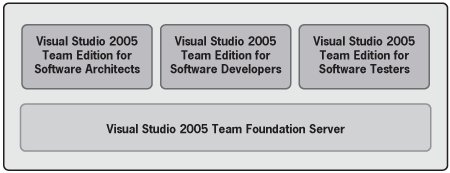

| Visual Studio 2005 Team System includes several different tools |

Visual Studio 2005 Team System recognizes this fact. As Figure 1-10 shows, this product suite includes components that target each member of a modern development group. Those components include: Visual Studio 2005 Team Edition for Software Architects: provides a group of tools known collectively as the Distributed System Designers. Each provides a DSL aimed at architects designing various aspects of service-oriented applications. These tools include Application Designer for defining applications and how they communicate, System Designer for defining how those applications fit together for deployment, Logical Datacenter Designer for defining the structure of machines in a data center, and Deployment Designer for defining how the set of applications that comprise a particular system is deployed in a specific data center. This product also includes a version of Visio that allows creating Unified Modeling Language (UML) diagrams, entity/relationship (ER) diagrams, and other architecture-oriented pictures. Visual Studio 2005 Team Edition for Software Developers: includes tools that are useful for people who actually write code. These tools support static code analysis, exposing problems such as using an uninitialized variable, dynamic code analysis, allowing code to be profiled for performance improvements, and more. Visual Studio 2005 Team Edition for Software Testers: offers tools focused on the tasks performed by people who test code, such as tools for creating and running unit tests and for load testing. Visual Studio 2005 Team Foundation Server: provides the common platform for the other Team System components. Implemented as a standalone server application, Team Foundation Server keeps track of team projects, maintains a work items database, supports version control of a project's source code, and provides other common services that a software development team needs. The projects maintained by a particular Team Foundation server can also be examined using a client called the Team Explorer. Status reports and other information are available through a Team System portal built on Windows SharePoint Services.

Figure 1-10. Visual Studio Team System provides different tools for different roles in a development team.

Except for Team Foundation Server, all of the components of Visual Studio 2005 Team System are built on Visual Studio 2005 Professional Edition, which means that each one includes a complete development environment. While many .NET developers are happy with just a standalone version of Visual Studio, larger teams or those working on more complex projects can sometimes make good use of the extra tools provided by Visual Studio 2005 Team Edition. |