Flexible Employment Arrangements for Streamlined Organizations

The rise of these organizational approaches has led to increased reliance on flexible employment arrangements. Today, over 25 percent of American workers are part-timers, independent contractors, or temps. When contract and on-call work is included, the share of the nation's workforce operating outside the confines of the traditional, full-time job grows to nearly 30 percent.[2] In high-tech regions, these numbers can be significantly higher (Benner 1996). One recent survey revealed that only one in three employed Californians holds a permanent, full-time, day-shift job working on-site (Institute for Health Policy Studies, 1999).

This system has so far worked well for the most talented and highly skilled workers. People at the top end of labor force have seen their incomes grow rapidly in recent decades, and for the most part they enjoy greater flexibility and more interesting work. One result, though, has been that at the high end of the work force, many talented managers and professionals continue to hold traditional jobs but no longer view themselves as company men or women. Instead, they consider themselves free agents, akin to professional athletes or Hollywood actors, who must look out for their own careers first and foremost. They see their current position as ephemeral, mostly useful as a way to develop or maintain their skills and thereby stay attractive in the job market. One partner at a leading professional services firm made an explicit analogy between professional sports and the situation in his company and other professional service firms: "If you look at the NFL or NBA, you have a reduced loyalty to the team…. The same is true in the workplace…. There's no loyalty to the team, but loyalty to money, or career".

The new system is less friendly to workers with modest skills, who have faced stagnant or declining wages and greater uncertainty. Less skilled workers feel waning allegiance to employers, largely because employers have shown less allegiance to them. During the 1990s, average job tenure declined and the rates of what labor economists refer to as "worker dislocation"—in everyday terms, "firings"— increased, all during the longest economic boom in the nation's history. Layoffs, which formerly occurred only during bad times, routinely took place even as firms reported record earnings (Osterman 1999; Jacoby 1999a, 1999b; Cappelli 1999b).

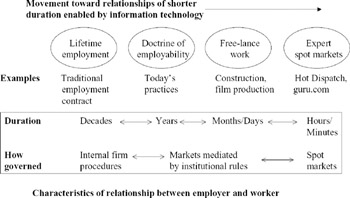

Given these developments, the old black-and-white classification—which defined the full-time, 9-to-5 job as the norm, and deemed everything else as "nonstandard"—is no longer an appropriate lens for viewing employment arrangements. A more useful approach is to think of jobs as being classified along a spectrum, according to the duration of the relationship between the employer and worker and the means used to govern the relationship (figure 17.1).

Figure 17.1: The Spectrum of Jobs

At one extreme are jobs where the employer-worker tie may last for decades, even for the entirety of the worker's career. The traditional employment contract of the mid-twentieth century worked in this way. At the other end of the usual spectrum is free lance work, in which the relationship typically lasts for several weeks or months—though in some cases, it may only be a matter of a few days. In the middle are relationships that can be expected to last longer than a few months, but not for multiple decades. Many of today's jobs fit this category, based as they are on an understanding that the relationship will continue only as long as it is mutually beneficial to both the employer and worker. Interestingly, the spectrum is now being extended into "jobs" that are shorter in duration—hours or even minutes—by Internet sites like Hot Dispatch and guru.com, which allow people with specialized knowledge to offer expertise on a spot basis to customers seeking advice or answers to specific questions.

In general, information technology and greater reliance on market-based patterns has moved the American workforce toward employment relationships of shorter duration. This movement has been most pronounced in the IT sector itself, where the need for rapid innovation has placed a premium on organizational flexibility, and where there has been the greatest familiarity with the technologies that enable new organizational approaches.

[2]The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Household Survey for April 2000 indicated that out of 135.7 million working Americans, 22.1 million were part-timers (16.3 percent) and 10.1 million (7.4 percent) were self-employed; see U.S. BLS (2000a). The BLS Establishment Survey for the same month indicated that 3.5 million Americans were employed in the Help-supply services industry, SIC Code 7363; see BLS (2000b). Given slight differences between the Household and Establishments surveys, a conservative estimate is that of the 135.7 million working Americans, 3.5 million (2.6 percent) are temporary workers employed by staffing companies. Of this 3.5 million, 0.6 million are part-timers, and already included in the figures for part-time workers derived from the Household Survey. This leaves 2.9 million (2.2 percent) working as full-time temps. Thus in April 2000, 25.9 percent of working Americans were part-timers, selfemployed, or full-time temps. In addition, for the same time period, 1.0 million (0.7 percent) were working in private households; see U.S. BLS (2000a). And the BLS survey on "alternative employment arrangements", conducted in February 1997, indicated that 1.6 percent of the workforce were on-call workers and another 0.6 percent were employed by contract firms; see Cohany (1998). When all six of these categories are included, 28.8 percent of American workers can be considered as not holding traditional full-time jobs.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 214