Research Design

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Planning Culture

Different considerations arise when measuring the culture construct. The first is whether culture should be measured qualitatively or quantitatively. Second, what level of culture is the most appropriate to measure, i.e., beliefs, values, norms, etc.? Another consideration relates to the level of analysis, i.e., organizational vs. planning culture, at which culture is to be considered.

Acknowledging that certain aspects of culture may not be accessible through a quantitative inquiry, Cooke & Rousseau (1988), however, asserted that quantitative methods are useful in studying some and not all aspects of organizational culture. Those aspects are related to the systematic effects of culture on individual behavior. The cultural manifestations that are mostly studied through an instrumental perspective are those connected with the means and operations used to achieve goals (Alvesson, 1989). Those are the kinds of cultural manifestations that were sought out in this research and for which we have set out to uncover their systematic effects on knowledge workers empowerment.

As to which level of culture to investigate, there is probably no one best way of doing so. It all depends on the perspective that one adopts on studying organizations. In this study, culture is used within a perspective on organizational change, wherein the instrumental impact of culture on IT planning effectiveness is to be reinforced through the mediating effect of empowerment. Therefore norms, as the most readily accessible elements of cultural content, should be the prime target for investigation (see Kilmann, 1989). Moreover, as the cultural construct of this study refers to a particular context of action, i.e., planning, and as the essence of the planning culture lies at the intersection of planning activities and knowledge workers, i.e., contextual beliefs held by knowledge workers, rather than being intrinsic to knowledge workers in a non-contextual fashion, there is a need for a context specific measure of culture. Kilmann (1989) argues for the use of norms rather than values when dealing with specific contexts:

"While norms are specific to a particular context, values can be conceptualized as more general oughts that transcend any one context...Norms and normative statements are concepts that suggest what an individual should or should not do in a specific situation. Values are seen as fairly independent from any one context" (p. 241).

Development of a Measurement Scale: In the IS area, there are few empirical studies that applied the cultural perspective to IS-related activities (Romm et al., 1991). Kumar & Welke (1984) and Kumar & Bjorn-Andersen (1990) used IS development related beliefs as measures of IS culture. In this study, however, a planning-related set of norms has been suggested as a more appropriate measure of a planning culture.

The related scale contains a list of items which express what norms knowledge workers hold toward IT planning (see Appendix A). The initial pool of items has been developed through an analysis of the existing literature on organizational planning in general and IT planning in particular. The survey instructions for the planning related norm-scale have been adapted from the Kilmann-Saxton Culture-Gap Survey (1983) and its modified and validated version by Saxton (1987). Each norm is stated in a dichotomous format. Respondents are asked to rate the strength of each norm along a six point ordinal interval bounded by the negative and positive statements of the norm. This format follows the structural model imposed by the theory of norms underlying the Kilmann-Saxton culture-gap survey. The latter has been widely used and validated in empirical research attempting to uncover and bridge cultural gaps measured as the difference between actual norms and desired norms (see Moore, 1993).

Empowerment

The literature on empowerment is marked by an overlap between enhanced control overwork-processes, feelings of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986; Burke, 1986), and intrinsic motivation (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990; Lee, 1987). They all seem to convey the same image, one wherein employees feel more confident and therefore more productive. Intrinsic motivation has been retained as the operational measure of empowerment because it is intuitively more task specific than self-efficacy, the latter being more a general trait than a contextual feeling, and more "emotionally charged" than "feelings of control over the work process." thus stressing the motivational nature of the construct.

Intrinsic motivation has been closely linked to organizational culture, the latter being a reinforcer of the former as the related hypothesis in this study states. Intrinsically motivated people behave consistently with an organization's culture because they have internalized the culture's values and traditions (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). Moreover, intrinsically motivated employees who have assimilated into the culture's value system know what to do and help others learn the culture by intervening where they see behavior that is inconsistent with their company's culture (Appelbaum et al., 1999).

Measurement Scale: The measurement of intrinsic motivation has been itself variable across studies because of diverging experimental settings of different studies. Nonetheless, two main recurrent types of measurement can be identified: behavioral and self-report (Lee, 1987). Task performance has been frequently used as a behavioral surrogate for intrinsic motivation (Hamner & Foster, 1975). This has been the landmark measure for experiment-based studies. On the other hand, the most frequently used self-report measure of intrinsic motivation is the Task Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) which taps individuals' task liking, feelings of accomplishment, feelings of being challenged, and feelings of using one's important abilities (Lee, 1987). Sahraoui (2001) used the TRQ as a model to develop a measure of intrinsic motivation within an IT planning context (see Appendix A). His measure was validated within a model of the effects of micro-planning behavior on IT planning effectiveness and has been adapted for this study, as it is situated within similar theoretical confines.

IT Planning Effectiveness

In this study, and in order to stay in-line with the theoretical developments about IT planning effectiveness, we depart from earlier studies of IT planning which have mostly defined IT planning effectiveness as the degree of fulfillment of IT planning objectives, improvement in performance of the IS function, and improvement in performance of the organization (Premkumar & King, 1991; Raghunathan & Raghunathan, 1991; Ramanujam et al., 1986). Other measures of performance of IT planning developed in the empirical literature include top-management commitment to and knowledge about IS, top management satisfaction with the planning process (Galliers, 1987), extent of implementation (Appelbaum et al., 1999), return on investment and improved organizational structure (Salmela, 2000), and absence of problems or audit checklists (Lederer & Sethi, 1988).

Salmela et al. (2000) argue however that different criteria for IS planning success should be chosen in different research contexts. This has been our approach in devising a performance measure for IT planning activities within the theoretical premises set above. Indeed, we contend that evaluating the effectiveness of the planning process can only be done in light of the theoretical mechanisms that link action to outcome. In this study, the planning culture enhances planning effectiveness by creating a learning environment where knowledge workers feel compelled to utilize and develop their knowledge and skills during the planning process. The effectiveness of IT planning can hence be appraised through what it purports to achieve, namely the learning accumulated by knowledge workers as a result of their involvement in IT planning.

Informal IT planning has been theoretically advocated as complementary to formal IT planning and hence as a means of alleviating some of the concerns related to the use of planning methodologies (see Earl, 1993, 1996). These concerns stem from the overemphasis of existing planning approaches on method at the expense of process and implementation. Following Earl's logic and the theoretical refinements developed above, we retained items (i.e., concerns) that expressed the level of learning allowed by the planning process as a surrogate measure for the effectiveness of IT planning. Earl developed a long list of concerns through an extensive empirical investigation of different planning approaches in 27 U.K. companies. The six items that have been retained for this study satisfy the criteria of face and content validity, and were filtered through an empirical keying process, which included all items developed by Earl. This scale had been earlier validated by Sahraoui (2001) in his study of the indirect effects of micro-planning behavior on planning effectiveness.

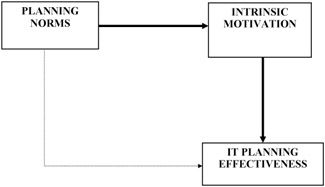

Based on the operational definitions above, a model of the empowering mediating effects of the planning culture on IT planning effectiveness is represented in Figure 2.

Sampling and Data Collection

A preliminary call for participation, assorted with a knowledge worker preselection scale, was sent to 420 members of an IT professional society in the State of Bahrain. Potential participants were asked to fill out and return the knowledge worker scale as well as personal contact information (see Appendix A). A total of 192 respondents were selected to receive the final questionnaire, as the rest did not qualify as knowledge workers. In case of doubt, the researcher called potential participants on the phone to further inquire on their professional status. The final tally of valid responses amounted to 101, which accounts for a response rate of 52%. This is deemed high for this kind of studies and is primarily due to the leadership position occupied by the author in the IT society and the personal follow up with individual respondents.

Validity and Reliability

The three scales used in this study show high scores on the standard reliability test of Cronbach alpha (see Table 1). Moreover, all constructs satisfied the content and external validity requirements. Hence all measurements are deemed valid and reliable.

| Scale | No of Items | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Motivation | 8 | .90 |

| Planning Norms | 15 | .96 |

| IT Planning Effectiveness | 6 | .89 |

Results

Hypotheses 1 and 2 were tested through simple regression and hypothesis 3 through path analysis. As shown in Figure 2, hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2 correspond to direct paths between two variables. By regressing each endogenous variable on the variable that directly affects it, we will be able to calculate and test for significance the two direct path coefficients. Table 2 summarizes the two regression equations with their results.

| Endogenous Variable | Var. with Direct Path to Endogenous Variable |

|---|---|

| IT Planning Effectiveness | Intrinsic Motivation |

| Beta Coef. = .83 | t-value = 16.85 [***] |

| Intrinsic Motivation | Planning Norms |

| Beta Coef. = .35 | t-value = 5.42[***] |

|

[***]P < .001 | |

The results of the two regressions support hypotheses 1 and 2. Knowledge workers' heightened intrinsic motivation translates into higher levels of IT planning effectiveness. Likewise, the planning norms significantly and positively impact knowledge workers' intrinsic motivation hence empowering them. Detailed discussions of both effects were developed earlier in this paper and are further provided in the next section.

Path analysis was used to test hypothesis 3. Path analysis is a technique that uses ordinary regression analysis to test variables in a causal sequence (Billings & Wroten, 1978; Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Joreskog & Sorbom, 1993). It provides a statistically efficient method for investigating complex relationships in which a dependent variable in one relationship subsequently becomes an independent variable in another postulated causal relationship (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1993). Advantages of path analysis are that it allows one to estimate the relative importance of alternative paths of influence and enables one to measure the direct and indirect (i.e., mediating) effects that one variable has on another (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Indirect effects of the planning culture on IT planning effectiveness are computed by multiplying the beta coefficients obtained through the two earlier regressions. In order for the data to support the theory, the indirect path coefficient should have a statistical value greater than zero (or deemed "meaningful," usually greater than .05, Billings & Wroten, 1978). Table 3 shows the result of the computation for the indirect path.

| Path Coef. of First Segment | Path Coef. of Second Segment | Indirect Path Coef. (P=S1*S2) |

|---|---|---|

| .35 | .83 | .29[*] |

|

[*]Path is significant at P > .05 | ||

The significance of the path lends support to hypothesis 3 of this study, namely that intrinsic motivation plays a critical mediating role for the effects of planning norms on IT planning effectiveness.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 191