Section 10.4. Text

10.4. TextIt's been said that Tkinter's strongest points may be its Text and Canvas widgets. Both provide a remarkable amount of functionality. For instance, the Tkinter Text widget was powerful enough to implement the web pages of Grail, an experimental web browser coded in Python; Text supports complex font-style settings, embedded images, unlimited undo and redo, and much more. The Tkinter Canvas widget, a general-purpose drawing device, allows for efficient free-form graphics and has been the basis of sophisticated image processing and visualization applications. In Chapter 12, we'll put these two widgets to use to implement text editors (PyEdit), paint programs (PyDraw), clock GUIs (PyClock), and photo slideshows (PyView). For the purposes of this tour chapter, though, let's start out using these widgets in simpler ways. Example 10-10 implements a simple scrolled-text display, which knows how to fill its display with a text string or file. Example 10-10. PP3E\Gui\Tour\scrolledtext.py

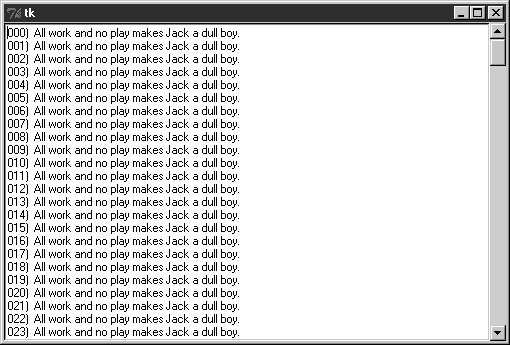

Like the ScrolledList in Example 10-9, the ScrolledText object in this file is designed to be a reusable component, but it can also be run standalone to display text file contents. Also like the last section, this script is careful to pack the scroll bar first so that it is cut out of the display last as the window shrinks, and arranges for the embedded Text object to expand in both directions as the window grows. When run with a filename argument, this script makes the window shown in Figure 10-15; it embeds a Text widget on the left and a cross-linked Scrollbar on the right. Figure 10-15. scrolledtext in action Just for fun, I populated the text file displayed in the window with the following code and command lines (and not just because I happen to live near an infamous hotel in Colorado): C:\...\PP3E\Gui\Tour>type temp.py f = open('temp.txt', 'w') for i in range(250): f.write('%03d) All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.\n' % i) f.close( ) C:\...\PP3E\Gui\Tour>python temp.py C:\...\PP3E\Gui\Tour>python scrolledtext.py temp.txt PP3E scrolledtext To view a file, pass its name on the command lineits text is automatically displayed in the new window. By default, it is shown in a non-fixed-width font, but we'll pass a font option to the Text widget in the next example to change that. Notice the PP3E scrolledtext message printed when this script runs. Because there is also a ScrolledText.py file in the standard Python distribution with a very different interface, the one here identifies itself when run or imported, so you can tell which one you've got. If the standard one ever goes away, import the one listed here for a simple text browser, and adjust configuration calls to include a .text qualifier level (the library version subclasses Text, not Frame). 10.4.1. Programming the Text WidgetTo understand how this script works at all, though, we have to detour into a few Text widget details here. Earlier we met the EnTRy and Message widgets, which address a subset of the Text widget's uses. The Text widget is much richer in both features and interfacesit supports both input and display of multiple lines of text, editing operations for both programs and interactive users, multiple fonts and colors, and much more. Text objects are created, configured, and packed just like any other widget, but they have properties all their own. 10.4.1.1. Text is a Python stringAlthough the Text widget is a powerful tool, its interface seems to boil down to two core concepts. First, the content of a Text widget is represented as a string in Python scripts, and multiple lines are separated with the normal \n line terminator. The string 'Words\ngo here', for instance, represents two lines when stored in or fetched from a Text widget; it would normally have a trailing \n also, but it doesn't have to. To help illustrate this point, this script binds the Escape key press to fetch and print the entire contents of the Text widget it embeds: C:\...\PP3E\Gui\Tour>python scrolledtext.py PP3E scrolledtext 'Words\ngo here' 'Always look\non the bright\nside of life\n' When run with arguments, the script stores a file's contents in the Text widget. When run without arguments, the script stuffs a simple literal string into the widget, displayed by the first Escape press output here (recall that \n is the escape sequence for the line terminator character). The second output here happens when pressing Escape in the shrunken window captured in Figure 10-16. Figure 10-16. scrolledtext gets a positive outlook 10.4.1.2. String positionsThe second key to understanding Text code has to do with the ways you specify a position in the text string. Like the listbox, Text widgets allow you to specify such a position in a variety of ways. In Text, methods that expect a position to be passed in will accept an index, a mark, or a tag reference. Moreover, some special operations are invoked with predefined marks and tagsthe insert cursor is mark INSERT, and the current selection is tag SEL. 10.4.1.2.1. Text indexesBecause it is a multiple-line widget, Text indexes identify both a line and a column. For instance, consider the interfaces of the basic insert, delete, and fetch text operations used by this script: self.text.insert('1.0', text) # insert text at the start self.text.delete('1.0', END) # delete all current text return self.text.get('1.0', END+'-1c') # fetch first through last In all of these, the first argument is an absolute index that refers to the start of the text string: string '1.0' means row 1, column (rows are numbered from 1 and columns from 0). An index '2.1' refers to the second character in the second row. Like the listbox, text indexes can also be symbolic names: the END in the preceding delete call refers to the position just past the last character in the text string (it's a Tkinter variable preset to string 'end'). Similarly, the symbolic index INSERT (really, string 'insert') refers to the position immediately after the insert cursorthe place where characters would appear if typed at the keyboard. Symbolic names such as INSERT can also be called marks, described in a moment. For added precision, you can add simple arithmetic extensions to index strings. The index expression END+'-1c' in the get call in the previous example, for instance, is really the string 'end-1c' and refers to one character back from END. Because END points to just beyond the last character in the text string, this expression refers to the last character itself. The -1c extension effectively strips the trailing \n that this widget adds to its contents (and may add a blank line if saved in a file). Similar index string extensions let you name characters ahead (+1c), name lines ahead and behind (+2l, -2l), and specify things such as line ends and word starts around an index (lineend, wordstart). Indexes show up in most Text widget calls. 10.4.1.2.2. Text marksBesides row/column identifier strings, you can also pass positions as names of markssymbolic names for a position between two characters. Unlike absolute row/column positions, marks are virtual locations that move as new text is inserted or deleted (by your script or your user). A mark always refers to its original location, even if that location shifts to a different row and column over time. To create a mark, call the text mark_set method with a string name and an index to give its logical location. For instance, this script sets the insert cursor at the start of the text initially, with a call like the first one here: self.text.mark_set(INSERT, '1.0') # set insert cursor to start self.text.mark_set('linetwo', '2.0') # mark current line 2 The name INSERT is a predefined special mark that identifies the insert cursor position; setting it changes the insert cursor's location. To make a mark of your own, simply provide a unique name as in the second call here and use it anywhere you need to specify a text position. The mark_unset call deletes marks by name. 10.4.1.2.3. Text tagsIn addition to absolute indexes and symbolic mark names, the Text widget supports the notion of tagssymbolic names associated with one or more substrings within the Text widget's string. Tags can be used for many things, but they also serve to represent a position anywhere you need one: tagged items are named by their beginning and ending indexes, which can be later passed to position-based calls. For example, Tkinter provides a built-in tag name, SELa Tkinter name preassigned to string 'sel'which automatically refers to currently selected text. To fetch the text selected (highlighted) with a mouse, run either of these calls: text = self.text.get(SEL_FIRST, SEL_LAST) # use tags for from/to indexes text = self.text.get('sel.first', 'sel.last') # strings and constants work The names SEL_FIRST and SEL_LAST are just preassigned variables in the Tkinter module that refer to the strings used in the second line here. The text get method expects two indexes; to fetch text names by a tag, add .first and .last to the tag's name to get its start and end indexes. To tag a substring, call the Text widget's tag_add method with a tag name string and start and stop positions (text can also be tagged as added in insert calls). To remove a tag from all characters in a range of text, call tag_remove: self.text.tag_add('alltext', '1.0', END) # tag all text in the widget self.text.tag_add(SEL, index1, index2) # select from index1 up to index2 self.text.tag_remove(SEL, '1.0', END) # remove selection from all text The first line here creates a new tag that names all text in the widgetfrom start through end positions. The second line adds a range of characters to the built-in SEL selection tagthey are automatically highlighted, because this tag is predefined to configure its members that way. The third line removes all characters in the text string from the SEL tag (all selections are unselected). Note that the tag_remove call just untags text within the named range; to really delete a tag completely, call tag_delete instead. You can map indexes to tags dynamically too. For example, the text search method returns the row.column index of the first occurrence of a string between start and stop positions. To automatically select the text thus found, simply add its index to the built-in SEL tag: where = self.text.search(target, INSERT, END) # search from insert cursor pastit = where + ('+%dc' % len(target)) # index beyond string found self.text.tag_add(SEL, where, pastit) # tag and select found string self.text.focus( ) # select text widget itself If you want only one string to be selected, be sure to first run the tag_remove call listed earlierthis code adds a selection in addition to any selections that already exist (it may generate multiple selections in the display). In general, you can add any number of substrings to a tag to process them as a group. To summarize: indexes, marks, and tag locations can be used anytime you need a text position. For instance, the text see method scrolls the display to make a position visible; it accepts all three kinds of position specifiers: self.text.see('1.0') # scroll display to top self.text.see(INSERT) # scroll display to insert cursor mark self.text.see(SEL_FIRST) # scroll display to selection tag Text tags can also be used in broader ways for formatting and event bindings, but I'll defer those details until the end of this section. 10.4.2. Adding Text-Editing OperationsExample 10-11 puts some of these concepts to work. It adds support for four common text-editing operationsfile save, text cut and paste, and string find searchingby subclassing ScolledText to provide additional buttons and methods. The Text widget comes with a set of default keyboard bindings that perform some common editing operations too, but they roughly mimic the Unix Emacs editor and are somewhat obscure; it's more common and user friendly to provide GUI interfaces to editing operations in a GUI text editor. Example 10-11. PP3E\Gui\Tour\simpleedit.py

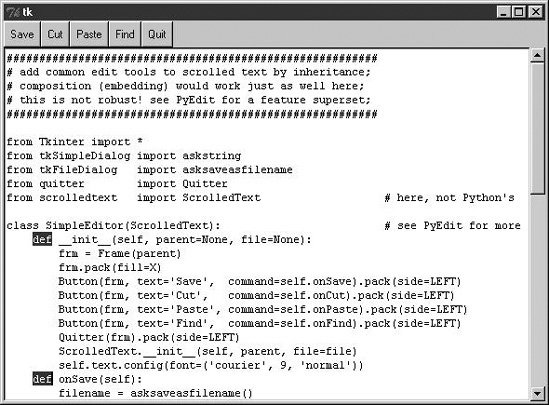

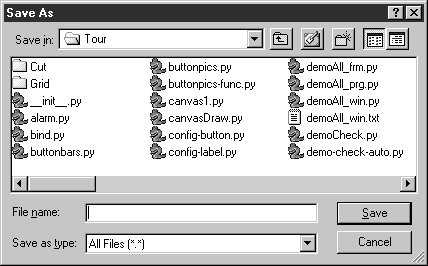

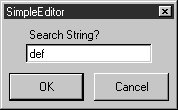

This, too, was written with one eye toward reusethe SimpleEditor class it defines could be attached or subclassed by other GUI code. As I'll explain at the end of this section, though, it's not yet as robust as a general-purpose library tool should be. Still, it implements a functional text editor in a small amount of portable code. When run standalone, it brings up the window in Figure 10-17 (shown running in Windows); index positions are printed on stdout after each successful find operation: C:\...\PP3E\Gui\Tour>python simpleedit.py simpleedit.py PP3E scrolledtext 14.4 24.4 Figure 10-17. simpleedit in action The save operation pops up the common save dialog that is available in Tkinter and is tailored to look native on each platform. Figure 10-18 shows this dialog in action on Windows. Find operations also pop up a standard dialog box to input a search string (Figure 10-19); in a full-blown editor, you might want to save this string away to repeat the find again (we will, in Chapter 12's PyEdit discussion). Figure 10-18. Save pop-up dialog on Windows Figure 10-19. Find pop-up dialog 10.4.2.1. Using the clipboardBesides Text widget operations, Example 10-11 applies the Tkinter clipboard interfaces in its cut-and-paste functions. Together, these operations allow you to move text within a file (cut in one place, paste in another). The clipboard they use is just a place to store data temporarilydeleted text is placed on the clipboard on a cut, and text is inserted from the clipboard on a paste. If we restrict our focus to this program alone, there really is no reason that the text string cut couldn't simply be stored in a Python instance variable. But the clipboard is actually a much larger concept. The clipboard used by this script is an interface to a system-wide storage space, shared by all programs on your computer. Because of that, it can be used to transfer data between applications, even ones that know nothing of Tkinter. For instance, text cut or copied in a Microsoft Word session can be pasted in a SimpleEditor window, and text cut in SimpleEditor can be pasted in a Microsoft Notepad window (try it). By using the clipboard for cut and paste, SimpleEditor automatically integrates with the window system at large. Moreover, the clipboard is not just for the Text widgetit can also be used to cut and paste graphical objects in the Canvas widget (discussed next). As used in this script, the basic Tkinter clipboard interface looks like this: self.clipboard_clear( ) # clear the clipboard self.clipboard_append(text) # store a text string on it text = self.selection_get(selection='CLIPBOARD') # fetch contents, if any All of these calls are available as methods inherited by all Tkinter widget objects because they are global in nature. The CLIPBOARD selection used by this script is available on all platforms (a PRIMARY selection is also available, but is only generally useful on X Windows, so we'll ignore it here). Notice that the clipboard selection_get call throws a TclError exception if it fails; this script simply ignores it and abandons a paste request, but we'll do better later. 10.4.2.2. Composition versus inheritanceAs coded, SimpleEditor uses inheritance to extend ScrolledText with extra buttons and callback methods. As we've seen, it's also reasonable to attach (embed) GUI objects coded as components, such as ScrolledText. The attachment model is usually called composition; some people find it simpler to understand and less prone to name clashes than extension by inheritance. To give you an idea of the differences between these two approaches, the following sketches the sort of code you would write to attach ScrolledText to SimpleEditor with changed lines in bold font (see the file simpleedit-2.py on the book's examples distribution for a complete composition implementation). It's mostly a matter of passing in the right parents and adding an extra st attribute name to get to the Text widget's methods: class SimpleEditor(Frame): def _ _init_ _(self, parent=None, file=None): Frame._ _init_ _(self, parent) self.pack( ) frm = Frame(self) frm.pack(fill=X) Button(frm, text='Save', command=self.onSave).pack(side=LEFT) ...more... Quitter(frm).pack(side=LEFT) self.st = ScrolledText(self, file=file) # attach, not subclass self.st.text.config(font=('courier', 9, 'normal')) def onSave(self): filename = asksaveasfilename( ) if filename: alltext = self.st.gettext( ) # go through attribute open(filename, 'w').write(alltext) def onCut(self): text = self.st.text.get(SEL_FIRST, SEL_LAST) self.st.text.delete(SEL_FIRST, SEL_LAST) ...more... The window looks identical when such code is run. I'll let you be the judge of whether composition or inheritance is better here. If you code your Python GUI classes right, they will work under either regime. 10.4.2.3. It's called "Simple" for a reasonFinally, before you change your system registry to make SimpleEditor your default text file viewer, I should mention that although it shows the basics, it's something of a stripped-down version of the PyEdit example we'll meet in Chapter 12. In fact, you should study that example now if you're looking for more complete Tkinter text-processing code in general. There, we'll also use more advanced text operations, such as the undo/redo interface, case-insensitive searches, and more. Because the Text widget is so powerful, it's difficult to demonstrate more of its features without the volume of code that is already listed in the PyEdit program. I should also point out that SimpleEditor not only is limited in function, but also is just plain carelessmany boundary cases go unchecked and trigger uncaught exceptions that don't kill the GUI, but are not handled or reported. Even errors that are caught are not reported to the user (e.g., a paste, with nothing to be pasted). Be sure to see the PyEdit example for a more robust and complete implementation of the operations introduced in SimpleEditor. 10.4.3. Advanced Text and Tag OperationsBesides position specifiers, text tags can also be used to apply formatting and behavior to all characters in a substring and all substrings added to a tag. In fact, this is where much of the power of the Text widget lies:

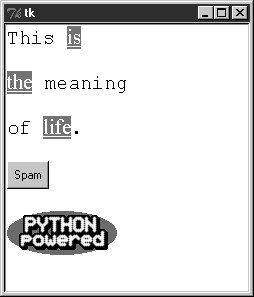

With tags, it's possible to display multiple configurations within the same Text widget; for instance, you can apply one font to the Text widget at large and other fonts to tagged text. In addition, the Text widget allows you to embed other widgets at an index (they are treated like a single character), as well as images. Example 10-12 illustrates the basics of all these advanced tools at once and draws the interface captured in Figure 10-20. This script applies formatting and event bindings to three tagged substrings, displays text in two different font and color schemes, and embeds an image and a button. Double-clicking any of the tagged substrings (or the embedded button) with a mouse triggers an event that prints a "Got tag event" message to stdout. Figure 10-20. Text tags in action Example 10-12. PP3E\Gui\Tour\texttags.py

Such embedding and tag tools could ultimately be used to render a web page. In fact, Python's standard htmllib HTML parser module can help automate web page GUI construction. As you can probably tell, though, the Text widget offers more GUI programming options than we have space to list here. For more details on tag and text options, consult other Tk and Tkinter references. Right now, art class is about to begin. |