Fragmented Minds--Do Not Standardize

|

|

Fragmented Minds—Do Not Standardize

Ambiguous responses to family communication concepts. Eighteen respondents (6 fathers, 6 mothers, 6 teenage girls) were interviewed in three focus group sessions about five concepts for mobile services to support communication within families.

New technologies rejected—new features required. Respondents’ perspectives on new solutions were confused. Even their basic attitude toward the concepts included acceptance and rejection side by side. On one hand, we heard disparagement of the “technological imperative” more than once. On the other hand, some of our service concepts were rejected because they didn’t exhibit enough genuine new benefits as compared to existing solutions. . . . Mobile, terminal-independent access is not necessarily a benefit as such if the consumer doesn’t see the value of it.

When you do sports, you do sports. No extra devices needed. I’m very much against the idea that our leisure time should be made so efficient. If we are “in chains” ourselves, do we have to chain our children, too?

I don’t like the idea that technology takes the responsibility from adolescents. They should learn to take responsibility themselves.

It doesn’t matter if we miss one training session with my son because of a last-minute change. Actually, that would give us a good chance to spend some shared time in peace for an hour.

Limited interests to share beyond a core group of intimates. People value their private time. Interest in close contact with others is limited to one’s own family and a few good friends. Parents don’t have much time and energy to sustain a wide range of social contacts. Making a point of keeping up with distant relatives was considered “mental,” not commendable. What motivates social community is shared interests and mutual goals, not just being a relative or neighbor. Parents were experienced users of information technology (IT) at work. They had experienced frustrations about using IT in that context. To them, leisure time is for privacy and relaxation, which leaves little room for new technologies. Face-to-face contact is preferred if you have something emotionally loaded to say.

One of my friends got invited to a funeral by SMS, and someone told me about a friend’s divorce by SMS. In my opinion that is completely tasteless and unacceptable.

Insulting associations to undesirable groups. Associating product features and usage scenarios to the wrong groups can be insulting. Finnish mothers got really upset when our designs seemed to connect them with household issues and children. Some working mothers said that they are so bombarded by that aspect of life that they’d prefer hobby-related scenarios instead. Associations with secondary comprehensive school implied by the scenarios insulted sixth-form girls.

After three years of staying awake nights with wailing infants, you’d rather see some stories about women having fun with friends.

Utility discussion rules. Utility discussion dominates the focus groups. This may be partly a methodological bias, but clearly it is also due to communication habits. Adults say that serious issues should be handled face to face or by voice calls. New fun and pleasure-optimized features are regarded almost like toys, and that’s a negative association. Toys are for kids, not for adults. Teenagers consider themselves adults or want to associate themselves with adults. Consequently, the objective for leisure communication is that the solutions have to be serious communication tools that can also be used for fun.

. . . on selected occasions—with 100% user control. Continuous communication of . . . needs to be under deliberate control. . . . Thus, the system needs to support . . . only for controlled specific reasons, in specific situations.

Only phone features are accepted. New . . . solutions need to be presented as features of a mobile phone. Operator service solutions, such as WAP services, caused a lot of mistrust. The reason was not completely clear, but probably it was related to expectations of costs, complexity, and difficulty of operation. When features are realized as network services, they must be seamlessly integrated with the terminal’s UI. New device categories for special purposes were not accepted.

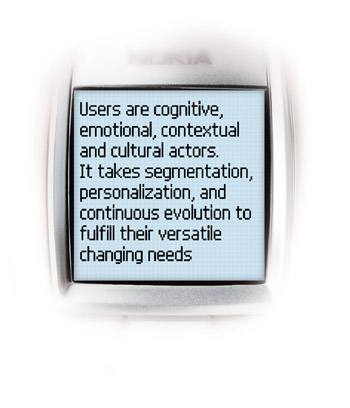

The market for mobile phones is a consumer product market. The easy approachability of user interfaces is an obvious objective, but not the whole objective. A person’s relationship with an artifact looks different depending on the angle of observation, and several angles may be relevant.

Every now and then I’m correctly interpreted as an information-processing unit accomplishing practical tasks with my handset. The next time I may be an actor trying to adapt my behavior to the surrounding circumstances. In other words, what I do makes sense only when seen in specific context. I may be a consumer choosing handsets, using handsets, exhibiting handsets, and speaking about handsets to construct and support my lifestyle and identity. I may be a participant in the wider cultural discourse evaluating mobile phones by socially constructed meanings. My behavior may be driven by my utilitarian or hedonistic motivations. I am a member of a culture, shaped and constrained by it. I’m also changing all the time along with the world around me, and occasionally I even do something myself to initiate a change.

Simple user segmentation models such as the ones based on demographic information or frequency of use are not enough. Individuals differ in several respects, even within themselves. Basic task-oriented usability is not enough. To improve user interface designers’ understanding of the multidimensional consumer, the designer must be empowered to see the shifting relevance of design tasks and to focus on what is essential.

Comprehensive user understanding has become topical for several reasons. A business expands into market areas and cultures that are relatively poorly known compared to the company’s previous experience. Simultaneously, in those markets where mobile technology has been most widely accepted, it has become an essential aspect of social life. Availing oneself of mobile phones and services is losing its novelty value. The enthusiasm of the user’s first foray has continued for a fairly long time, and there is reason to get ready for normalized markets. Naive users are being replaced by hard-to-satisfy people who are accustomed to versatile IT applications and devices. Usage and consumption motivations and patterns have to be classified better than before.

The fragmentation of the user population has two kinds of implications: those for the method set and those for the product portfolio. Longitudinal studies, contextual design, and cultural research are tools intended to deepen our insight into the consumers’ lives. The tools come from sociological and ethnographic research traditions, and are being adjusted for the product development environment.

One size does not fit all. A range of models is needed, and product segmentation has to percolate to the level of user interfaces: screen sizes, control elements, operational logic, features, language, shortcuts, graphics, and sounds. All the components of user interaction need to be designed so as to satisfy versatile demands. Simple design assumptions, such as using English as the default UI language in the design phase and then translating the vocabulary later, just do not work. Other languages have essentially longer expressions to be accommodated on the small screens. The layout design needs to be verified with several languages.

Providing UI diversity starts with the user interface style portfolio and ends in UI personalization.

|

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 142

- The Second Wave ERP Market: An Australian Viewpoint

- Distributed Data Warehouse for Geo-spatial Services

- Intrinsic and Contextual Data Quality: The Effect of Media and Personal Involvement

- A Hybrid Clustering Technique to Improve Patient Data Quality

- Relevance and Micro-Relevance for the Professional as Determinants of IT-Diffusion and IT-Use in Healthcare