Browsers

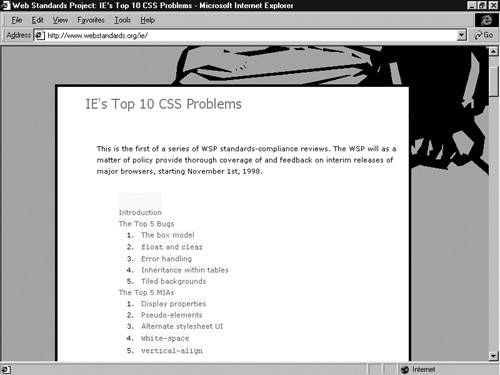

| The CSS saga is not complete without a section on browsers. Had it not been for the browsers, CSS would have remained a lofty proposal of only academic interest. The first commercial browser to support CSS was Microsoft's Internet Explorer 3, which was released in August 1996. At that point, the CSSI specification had not yet become a W3C Recommendation and discussions within the HTML ERB were to result in changes that Microsoft developers, led by Chris Wilson, could not fore-see. IE3 reliably supports most of the color, background, font, and text properties, but it does not implement much of the box model. The next browser to announce support for CSS was Netscape Navigator, version 4.0. Since its inception, Netscape had been sceptical toward style sheets, and the company's first implementation turned out to be a half-hearted attempt to stop Microsoft from claiming to be more standards-compliant than Netscape. The Netscape implementation supports a broad range of features for example, floating elements but the Netscape developers did not have time to fully test all the features that are supposedly supported. The result is that many CSS properties cannot be used in Navigator 4. Netscape implemented CSS internally by translating CSS rules into snippets of JavaScript, which were then run along with other scripts. The company also decided to let developers write JSSS, thereby bypassing CSS entirely. If JSSS had been successful, the Web would have had one more style sheet than necessary. This, fortunately for CSS, turned out not to be the case. Meanwhile, Microsoft continued its efforts to replace Netscape from the throne of reigning browsers. In Internet Explorer 4, the browser display engine, which among other things is responsible for rendering CSS, was replaced by a module code-named "Trident." Trident removed many of the limitations in IE3, but also came with its own set of limitations and bugs. Microsoft was put under pressure by the Web Standards Project (WaSP), which published "IE's Top 10 CSS Problems" in November 1998 (see Figure 18.1). Figure 18.1. The WaSP project tracks browser conformance to W3C Recommendations. One of their first reviews was the CSS support in Microsoft Internet Explorer. Subsequent versions of Internet Explorer have improved the support for CSS, but important functionality is still missing (for example, "fixed" positioning, generated text, and user-selectable style sheets). In this book, we review Version 6 of Internet Explorer. The third browser that ventured into CSS was Opera. The browser from the small Norwegian company made headlines in 1998 by being tiny (it fit on a floppy!) and customizable while supporting most features found in the larger offerings from Microsoft and Netscape. Opera 3.5 was released in November 1998, and supported most of CSSI. The Opera developers (namely Geir Ivarsøy) also found time to test the CSS implementation before shipping, which is a novelty in this business. One of the authors of this book, Håkon, was so impressed with Opera's technology that he joined the company as CTO in 1999. Since then, Opera Software has grown and now has about 200 employees. One important market for Opera's browser is mobile phones. By reformatting pages to fit on a small screen (@media handheld is handy here), the Web has been freed from the desktop (see Figure 18.2). Figure 18.2. Opera's "small-screen rendering" transforms pages into columns. The people at Netscape responded to the increasing competition with a move that was novel at the time: They released the source code for the browser. With the source code public, anyone could inspect the internals of their product, improve it, and make competing browsers based on in. Much of the code, including the CSS implementation, was terminated shortly after the release, and the "Mozilla" project was formed to build a new generation browser. CSS was in important specification to handle and countless hours have been spent by volunteers to make sure pages are displayed according to the specification. Several browsers have been based on the Mozilla code, including Galeon and Firefox. Apple is often seen as a technology pioneer, but for a long time, it did not spend much resources on Web browsers. Apple left it to Microsoft to build a browser for its machines, and Internet Explorer for Mac actually had better support for CSS than the Windows version of the browser. In 2003, Microsoft discontinued support for the Mac and Apple announced a new browser called "Safari." Safari isn't entirely new it is based on the open source Konqueror browser, which was developed for the KDE system running on Linux.

For Web designers, it is good news to have several competing products based on Web standards. Although some efforts to test that your pages display well in all browsers are necessary, the fact that Web pages can be displayed on a wide range of machines is a huge improvement from the past:

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 215