1 - Development and epidemiology

Editors: Goldman, Ann; Hain, Richard; Liben, Stephen

Title: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children, 1st Edition

Copyright 2006 Oxford University Press, 2006 (Chapter 34: Danai Papadatou)

> Table of Contents > Section 1 - Foundations of care > 1 - Development and epidemiology

1

Development and epidemiology

Simon Lenton

Ann Goldman

Nicola Eaton

David Southall

Introduction

All over the world children are living with and dying from life-threatening illnesses in a wide variety of social, economic, and health environments. Paediatric palliative care with its broad approach to symptom management, psychosocial, spiritual, and practical care has the potential to help enormously in the care and relief of suffering of these children and their families, particularly as it is relatively inexpensive and low tech . However the vast majority of those children who die do so in the less developed countries where palliative care, as yet, has had almost no impact on their management. Even in the industrialised countries where palliative care is emerging as a new specialty, the provision of care is still extremely uneven, both between different countries and within each country individually. On the other hand, considering the modern concept of paediatric palliative care, or hospice care as it is often called in the United States, was unknown before the 1970s, it is remarkable how widely it has developed in less than 30 years and how much contribution it is already making.

The development of palliative care in paediatrics

Looking back in the literature the need to consider the problems for children with life-threatening and terminal illness seems to have become apparent synchronously to a number of different people, including both innovative health care workers and also individuals who had been affected personally [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. It's not easy to trace the origins of an idea and exactly why a particular time was right for its development. A combination of factors seem to have been involved. One major influence must have been awareness of the growing strength and benefits of the adult palliative care movement, particularly following the opening of St Christopher's Hospice in 1967. Further less tangible factors seem to have been the changing attitudes to health care and to the relationship between health care professionals and patients, particularly in the developed countries. Here society has been taking a more active interest in holistic approaches to health care and also there has been a trend away from a patriarchal and all-powerful health care system with increasing emphasis on personal autonomy. This shift has enabled families to express their wishes and needs (such as to care for their dying child at home) more clearly, and also the nurses and doctors have been more willing to listen and respond than in the past.

Many of the earlier paediatric palliative care projects were inspired by individuals with a powerful commitment relating to a personal experience of a child with a life-threatening illness, often combining the complex desire to improve the situation for the future and also to provide a lasting memorial to their loved one. Some families took a very active role and channelled great energy and commitment into developing projects through charitable funding. Helen House and many of the other children's hospices are named after particular children, as is the Edmarc programme in the United States [9, 10]. Professionals too describe personal stories influencing their work in the field [11].

Offering a realistic choice to families of where they provide palliative care for their child and providing support and care in these different environments has been one of the core themes in paediatric palliative care. In the resource rich countries, a range of models of home care programmes are working towards this, supplemented by the development of children's hospices, respite care services, hospital-based initiatives, and bereavement programmes. In the developing countries, the provision lags far behind with local resources, priorities, and geography influencing the possibilities of providing palliative care. Those programmes that are beginning to develop are through community and home-based paediatric initiatives or in association with an established adult palliative care programme.

P.4

Home care

The earliest reported programmes developed in the United Kingdom and the United States. Specialist cancer services were among the first to recognize the need for palliative care [12, 13, 14, 15]. The majority of services developing for children with malignant diseases were hospital based, originating in oncology units, depending often on specialist nurses, and in some more multidisciplinary teams. They offered palliative care support to families from a range of different services (Table 1.1).

In the United Kingdom palliative care for oncology patients was from the time of diagnosis, whereas in the United States the structure of their health care and insurance systems resulted in teams tending to focus on children with later stage and terminal illnesses. In contrast with adult palliative care, many home care programmes recognised, from very early on, the importance of including children dying from a wide range of illnesses, not just cancers [10, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. The teams with a brief to care for all children with all life-limiting and terminal illness had more diverse origins than the oncology teams. Some began from a hospital-based oncology focus and then extended their role [16]. Others were community [10, 18, 20] or hospital [17, 19] based.

As paediatric palliative care has expanded, so the range of models of care has also extended, to fit in with local ideas, clinical need, resources, cultures, and health care systems. Teams have in common the basic principles of providing expertise in symptom management, psychosocial, spiritual, and practical support, but vary in aspects of day-to-day operation such as size, staffing, funding, links with hospital and community, and links with children or adult hospices. The literature has many descriptions of individual teams and their approaches. In addition many more are established and are providing care are but are not formally described. There has still been very little evaluation and comparison between the different types of home care teams.

Table 1.1 Different components of palliative care | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Inpatient care

Only one hospital with a dedicated inpatient paediatric palliative care service is reported in the early literature [17, 21]. This was established at St Mary's Hospital in New York in 1985 as part of a wider programme for children with all life-threatening illnesses, and also included home care. It was initiated at a time when AIDS was emerging as a major problem. Interestingly, although the hospital continues to have a strong commitment to palliative care and an outpatient and home care programme, their inpatient unit was closed in the late 1990s [11]. A combination of factors are cited for this change including negative perceptions of the unit within the hospital and community, intensity of emotions for staff, parents, and children, and the changing outlook for patients with AIDS. Palliative care is now provided by their multidisciplinary teams throughout the hospital.

Much more recently, three hospitals in the United States have reported dedicated paediatric hospice beds [22] but no details are given. Others have initiated programmes, special rooms, and family facilities to bring the hospice philosophy to relevant patients and families in their units [23, 24].

Most hospital-based teams have chosen to adopt a consultative role rather than develop specific inpatient facilities. Some, like the oncology outreach teams, already had a close link to a particular diagnostic group of patients and are involved with them both in hospital and at home. Others have a wider range of diagnostic groups under their care. They may offer only inpatient care and help co-ordinate discharge but many combine this with a home care programme after discharge.

These generic hospital-based services are increasingly common in well-resourced countries. They vary in size and multidisciplinary constitution, but tend to have a nursing core with medical input and contributions from a wide range of other professionals (e.g. psychologists, social workers, play therapists, chaplains, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists, art and music therapists). The reasons for referrals within the hospital are often complex, relating to difficult ethical decisions, communication problems, and staff support as well as the expected symptom management, family support, and discharge planning.

An emerging theme is the potential for valuable co-operation between palliative care teams and paediatric intensive care units [25]. This provides the opportunity to work together with families exploring the type of care that will be in the best interest of their child at the end of life. This is especially helpful for those with progressing prolonged illnesses and previous intensive care unit admissions. This close mutual relationship between palliative care and intensive care interest

P.5

is also reflected by the intensive care background of a number of the paediatric palliative care physicians.

Children's hospices

Helen House was the first freestanding children's hospice facility and opened in the United Kingdom in 1982. It provides an attractive eight-bedded home-from-home unit, with play rooms, gardens, and family accommodation and staffed by a multidisciplinary team [7, 9, 26, 27]. It has always been available to children with all life-limiting illnesses but found that most of the children admitted have longer-term illnesses such as metabolic or neurodegenerative diseases. Although a proportion of their patients receive terminal care the majority of admissions are for respite care. Families including siblings are supported throughout the illness and their bereavement. Helen House is a voluntary organisation and funded independently from charitable donations but works alongside the National Health Service.

The initial response to Helen House was ambivalent both from the paediatric establishment [28, 29, 30] and from adult palliative care [31]. Even Frances Dominica, the founder, herself felt that the need for more children's hospices was unlikely [27]. However, there are now 23 children's hospices open and 15 more planned in the United Kingdom as well as those that have now open or are being planned in Australia, Germany, Canada, Holland, and the United States.

Helen House has been a model for most of these children's hospices, but each has developed its own particular character and strengths with some now having close links with an adult hospice, some with links to local children's hospitals, and others with outreach and home care teams or day care facilities. Recently, hospices focusing specifically on the needs of adolescents and young adults have opened.

Parents value the standard of care and support, staff commitment, and the environment of the children's hospices [32, 33] but the financial costs are considerable and concern has been expressed that children's hospices will face challenges as they move beyond the pioneering phase to become embedded in regular health and social care structures [34, 35].

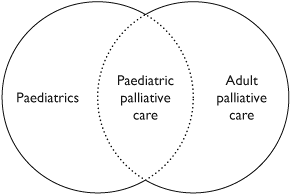

Adult palliative care

Paediatric palliative care sits in the overlap between the two much larger and more established fields of paediatrics and of adult palliative care (Figure 1.1). Its boundaries are distinct but should not be impermeable. From this central position children's palliative care stands to gain from the knowledge and experiences of both and also to contribute to both. Working in close co-operation should be to everyone's mutual benefit. However, in this situation, particularly, whilst paediatric palliative care develops and clarifies its role and as its voice strengthens, there can also be some difficulties, with confusion about its particular expertise. Some paediatricians do not understand the contribution that palliative care can make to their patients and others can fail to recognise their own limitations in providing it. Adult palliative care professionals may not acknowledge the special needs of children and families and the changes in practice needed for this. These special needs are being acknowledged both by those in paediatric palliative care [36, 37] and also by adult palliative care teams with some familiarity caring for children [38, 39].

The common features for both adult and children's palliative care include:

Threat to life

Impact of symptoms on activities of daily living

Emotional impact

Distress to families

Need for a co-ordinated multi-agency approach.

There are, however, significant differences:

Death in childhood is relatively rare in well resourced countries.

The range of illnesses is different wide range, often rare, often genetic, serious learning difficulties are common, varied time course, and crises can be rapid and unpredictable.

Developmental factors influencing physiology and pharmacokinetics fluids, nutrition, choice of medication, doses, side effects.

Developmental factors influencing cognitive and emotional understanding special skills in communication, assessment, art, music, play, education.

Family care working alongside parents as primary care givers, parent education, parent support, siblings, grandparents.

|

Fig.1.1 Paediatric palliative care between paediatrics and adult palliative care. |

P.6

Ethical issues child's developing autonomy, parents role, professionals role, decisions, respecting parents whilst including children.

Grief in parents and siblings may be more severe.

Multiple professionals and sites of care teamwork, communication, home, hospital, hospice, school.

Emotional strain and difficulty with boundaries for staff especially those not used to caring for dying children.

Those familiar with adult palliative care are likely to find the least differences working with families when a child is dying from malignant disease, especially with older children. With other illnesses such as metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases and with infants the differences are greater. Adult palliative care teams will need to work closely alongside paediatricians to manage the day-to-day care of a child with profound physical and developmental disability, with fluctuating health problems over long periods, possible behavioural difficulties, and the need for respite care. Care at home is, by its nature, child and family orientated and adult home care teams can accommodate their roles relatively easily to work with families here. In contrast, adult inpatient hospice care may be less easily adapted with difficulties arising both for the children and families, the hospice staff, and the other adult palliative care patients.

In many countries, especially those with a large geographic area and a small population, the only realistic way children will be able to receive palliative care will be through a co-operation of paediatric and adult health care professionals. Good communication and recognition of each other's roles become essential. This joint approach is currently widespread and is likely to be the only way children have access to paediatric palliative care in many parts of the world in the foreseeable future.

Definitions in paediatric palliative care

When starting to develop palliative care services, it is important for individuals and agencies involved to have a shared understanding of what they want to achieve. They, therefore, need to define what palliative care is and the children and families who might benefit.

What is paediatric palliative care?

Traditional, adult orientated, definitions of palliative care which have been used are:

Palliative care is the active total care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment. Control of pain, of other symptoms and of psychological, social and spiritual problems is paramount. The goal of palliative care is achievement of the best possible quality of life for patients and their families [40]

Palliative care is active total care offered to a patient with a progressive illness and their family when it is recognised that the illness is no longer curable, in order to concentrate on the quality of life and the alleviation of distressing symptoms within the framework of a co-ordinated service [41]

These definitions presume that curative treatment is an option, but for many children their conditions have no curative options. Neither does the term progressive illness fit comfortably with children's palliative care, where many of the children have non-malignant life-threatening conditions that may not in themselves be progressive, but are likely to limit the child's life.

The definition of children's palliative care is evolving with time. The most frequently quoted definitions are:

Palliative care is an active and total approach to care, embracing physical, emotional, social and spiritual elements. It focuses on enhancement of quality of life for the child and support for the family and includes the management of distressing symptoms, provision of respite, and care following death and bereavement [42]

The goal of palliative care is the achievement of best quality of life for patients and their families, consistent with their values, regardless of the location of the patient [43]

At one level, these broader definitions cover the care that most clinical practitioners would strive to achieve for all the children and families they are involved with, regardless of their diagnoses, threat to life, or other circumstances. However, where the survival of the child is limited with a life-threatening condition, there is a greater emphasis on the emotional and spiritual well-being of all family members throughout the child's life.

Which children will benefit from palliative care?

The ACT definition above does not specify which children should benefit from palliative care. Because it assumes that palliative care starts when a diagnosis of a life-threatening condition is made, rather than the terminal phase as in adults, there is inevitably a degree of prognostic uncertainty for a substantial number of children. The largest group where there is uncertainty is of those with static neurological conditions, mainly quadriplegic cerebral palsy, who quite frequently deteriorate during the increased demands of adolescence and early adult life. Further work still needs to be undertaken to determine more accurately the life expectancy for this group of children and young people, within different societies/health care systems [44, 45, 46, 47].

P.7

The four broad groups of children which have been delineated [42] are those with:

life-threatening conditions for which curative treatment may be feasible but can fail. Children in long term remission or following successful treatment are not included (e.g. cancer, organ failures);

conditions where premature death is inevitable, where there may be long periods of intensive treatment aimed at prolonging life and allowing participation in normal activities (e.g. cystic fibrosis);

progressive conditions without curative treatment options, where treatment is exclusively palliative and may commonly extend over many years (e.g. Batten disease, mucopolysaccharidoses);

Irreversible but non-progressive conditions causing severe disability leading to susceptibility to health complications and likelihood of premature death (e.g. cerebral palsy).

Issues which need to be addressed for planning clinical service delivery

Definitions of childhood. Definitions range from conception to 21 years through to birth to 14 years. Many children with non-malignant life-threatening conditions have associated learning difficulties and consequently attend special schools up to the age of 19 years. An upper limit of 19 years, therefore, seems appropriate in the United Kingdom as school health services continue to be involved. A definition of childhood needs to be considered when establishing a clinical service.

Duration of threat to life. Definitions tend to assume long-term conditions and fail to take into account conditions that are life-threatening for a limited period, for example, extreme prematurity, injuries, or acute diseases such as meningitis. For a short time, these conditions may pose a serious threat to life and the needs of these families may be similar to those who have a child with a longer-term illness. Hence, there needs to be clarity about the inclusion of acute illness or injury in the service plan.

Degree of threat to life. Children with diabetes are not usually considered as having a life-threatening illness, however, life expectancy is normally reduced and there is a threat to life during periods of poor control. However, the actual risks are relatively small and with good control life is not significantly shortened, even though some families may perceive the risks as significant. An estimate of the degree of threat to life needs to be included.

Death in childhood. Many definitions suggest that death should occur in childhood despite the fact that prediction of death is so difficult. Increasingly, many conditions that were universally fatal in childhood are now not causing death until early adulthood. Cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and some cardiac conditions are all examples. Death in childhood is not essential for children to be included within a service.

Most parents presume to die before their children, and examining patterns of age at death, there is a nadir around 40 years of age by when most young people with fatal conditions, starting in childhood, have died. Therefore, the term premature death in the definition, meaning expected to die before their parents, rather than stating death by a specific age is preferable.

Changing prognosis. Seventy per cent of children with leukaemia now survive; cystic fibrosis used to be a fatal condition within childhood, but estimates of average survival are ever increasing and have now almost reached 40 years [48]. Likewise, HIV/AIDS used to be a fatal diagnosis, but with early treatment with anti-retrovirals and effective treatment of intercurrent infections, HIV is beginning to be seen as a long-term infectious disease rather than a fatal disease in developed countries. In any definition of children's palliative care an estimate of probability of death or life expectancy should be considered, recognising that this may change over time.

Condition based definition. Definitions that are based on diagnoses are unhelpful due to the clinical variability of individual conditions, so some may, and others may not, be life-threatening. Occasionally a life-threatening illness is recognised, but no formal diagnosis is possible. An entirely condition/diagnosis-based approach to definition is unhelpful, rather a non-categorical approach based on life expectancy is recommended [49].

Severity/impact on daily living. There are many children and young people with multiple complex disabilities whose life expectancy is not appreciably shortened, yet their condition has a profound impact on their lives and on family functioning, for example, classical autism. On the other hand, boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy may have a long period of life without a very significant disability and yet their prognosis in terms of years of life may be worse than the child with the severe but static neurological condition. Levels of support/input to the family will be more related to impact on quality of life and morbidity than the duration of the condition, so severity/impact does not influence the definition, but does significantly impact on service provision.

P.8

Severe mental health diagnoses. It can be argued that severe anorexia nervosa or depression associated with suicidal behaviour, also have a high probability of death and should therefore be included as life-threatening conditions. However, because of their need for specialist psychiatric services, they are normally excluded from the definition of palliative care for children.

Technology dependent children. Technology-dependent children are those children: who need both a medical device to compensate for the loss of a vital bodily function and substantial and on-going nursing care to avert death or further disability [50, 51].

Included would be children requiring mechanical ventilation, parenteral nutrition, and peritoneal dialysis. These children are dependent on technology for survival, and using this technology they may not be expected to die prematurely. Many children who have life-threatening illnesses are also dependent on technology to improve the quality of their lives, for example, gastrostomies for feeding, night-time ventilation for children with neuromuscular conditions. Technology dependence per se does not determine whether palliative care is needed.

Preventability/treatability of conditions. Millions of children die worldwide from starvation and infectious disease; their death is inevitable, often uncomfortable and lonely, but they are not perceived as needing palliative care. On the other hand, hundreds of thousands of children die from AIDS, often through starvation and infectious disease, and yet these children are perceived as requiring palliative care. The definition of palliative care should exclude children with easily treatable or preventable conditions.

Bereavement care. This is an integral part of the work of the palliative care team. However, those children who die acutely and never reach a hospital, for example, victims of house fires or road traffic accidents, or those who die in emergency departments or intensive care units, generally, receive their on-going care from the team involved at the time. A decision needs to be made as to whether the palliative care team should be involved with those families where the child was not known to the team before death. This often depends on whether there is an adult bereavement service already in existence, and how comfortable they feel with the specific issues around the deaths of children.

In conclusion, defining the role for palliative care needs to be society and health service specific and recognise that resources are not unlimited. In some situations, greater health gain could be achieved with alternative investment strategies, which may mean focusing on prevention rather than intervention, in other situations, focusing and management of symptoms and supportive care will benefit a much larger number of children than introducing expensive interventions for a few. Transplantation for organ failure may be an option in some countries, but not in others, likewise, access to life-giving technology will not necessarily be universally available, or indeed culturally acceptable.

Each service therefore needs to develop a clear definition based on factors discussed above and the resources available, and then to inform parents and other professionals of the criteria for referral to the service. For example the following definition used for referrals to one community-based palliative care team in the United Kingdom, is pragmatic, clear, and has clinical relevance to those making referrals [13].

A life-threatening condition [in childhood] is any illness or condition developed in childhood (before the age of 19 years) whereby the child is likely (a probability of greater than 50%) to die prematurely (before the age of 40 years), or any condition developed in childhood that without major intervention (which itself carries a significant mortality) will result in the child dying prematurely. Short term/acute illness/injury and mental health diagnoses are excluded.

Epidemiology of life-threatening conditions

Definitions in epidemiology

Classical epidemiology studies the incidence and prevalence of diseases or conditions in the population and their association with either causal factors or outcomes. Clinical epidemiology considers the effectiveness of tests, investigations, and interventions and when combined, the two epidemiological approaches complement one another to determine need (the ability to benefit from services) and the burden of disease in society.

Incidence is the number of new cases occurring in a defined population over a specified period of time. It can also be applied to the number of deaths in a defined population over a specified period of time. It is particularly useful for acute illnesses or events, for example, meningitis or sudden infant death syndrome.

Prevalence is the number of cases in a defined population over a specified time period. It is particularly relevant to long-term conditions.

point prevalence is the number of cases in a defined population at one moment in time

period prevalence is the number of cases in a defined population over a defined period of time.

Prevalence cannot be derived from incidence, unless length of life is known. Generally, more children are surviving, and

P.9

for longer periods of time, so the incidence of death in childhood is decreasing, and prevalence of children needing palliative care increasing.

In the absence of an agreed international definition of a life-threatening condition it is not possible to provide comparative figures on a global basis for children who require palliative care. Review of a global perspective of palliative medicine for adults is included in the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine [52].

Global epidemiology of mortality

Children living in poorly resourced countries today, face problems similar to children now living in the well-resourced nations in previous centuries, often with the additional burden of tropical diseases and armed conflict. In many developed nations, infant mortality is now below 10 per 1000 births compared to many developing countries where it is still above 100 per 1000 births. These gains in life expectancy are due primarily to a decrease in deaths from infectious diseases. Consequently, health services in developed countries have shifted their focus to longer-term conditions as the predominant causes of morbidity and mortality [53].

There are approximately 1.5 billion children in the world and 85% live in poorly resourced countries. Approximately, 11 million children will die before they reach the age of five. Sixty per cent lack sanitation, 30% lack safe water, and 20% have no access to health care. Malnutrition affects around a third of children under 5 years of age and is implicated in more than 50% of the deaths [54, 55].

It is estimated that 63% of these deaths could have been prevented with a few simple, affordable, and effective health interventions. For example 26% of the world's children go without immunisations, 28% receive no oral rehydration therapy, 40% receive no antibiotics for pneumonia, 58% are not breast-fed for the first 4 months, and 32% do not have access to sufficient iodine [56, 57, 58, 59].

Poverty is the largest remediable cause of excess mortality. A total of 1.3 billion people live on less than one dollar a day while the world's 358 richest individuals have a combined wealth equivalent to the annual income of the poorest 2.3 billion people (nearly half the world's population), or alternatively, the richest 1% of the world's richest population have a combined income equivalent to 57% of the world's poorest [60, 61, 62].

More worryingly, in the poorest countries there has been very little improvement in wealth over the last decade. These inequalities are becoming greater over time, with Europe's per capita income now being 13 times greater than Africa's, which represents a fourfold increase over the last century. Indeed, overall measures of human development have fallen in 21 countries during the last decade [57, 58, 59].

The effects of war and conflict are a major cause of mortality and morbidity in children. In the ten years before 1998 two million children were killed by war, 4 million children were permanently disabled, 1 million children orphaned and 12 million children displaced [63].

Every year over half a million women die from pregnancy-related causes, leaving one million motherless children, who will then often be more vulnerable to disease. Girls in Sudan are ten times more likely to die in pregnancy than complete primary school education [64].

Worldwide 2 billion people are currently infected with hepatitis B, causing 1 million deaths per year. A further 2 billion people are infected with tuberculosis, with 300,000 new cases each year. Over 36 million adults were estimated to be living with AIDS at the end of 2000 and 1.3 million children worldwide are living with HIV. In 2001, there were 3 million deaths from HIV/AIDS-related infections; in Kenya alone, 700 people die each day from HIV/AIDS. Many long-term viral infections are associated with an increased risk of cancer, for example, HIV and Kaposis sarcoma, herpes and cervical carcinoma, or hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma, all further adding to morbidity and burden of disease.

Epidemiology in developed nations

Estimates of incidence from death certification

There are no systematic reviews, equivalent to those in the adult literature [65], examining the need for palliative care in childhood. Horrocks et al. [66] reviewed UK data for non-malignant disease and concluded that current literature was inadequate and recommended systematic research to accurately identify children with specified life-threatening conditions.

All reported incidence studies are based on the incidence of death rather than diagnosis, as information systems do not exist to reliably identify children with life-threatening illnesses at the time of diagnosis.

In one of the earliest UK estimates, based on an extrapolation of 1986 mortality data of 0 16 year olds, Thornes [67] suggested that there were 5400 children with life-threatening diseases. These figures suggest a prevalence of 4.9 children per 10,000, with 1.46 per 10,000 deaths per annum. Using OPCS data on child deaths over a 5-year period (1987 1991). While [68] calculated the incidence of deaths (all causes) for children aged 1 17 years in England and Wales as 10 per 100,000 per annum.

Jones studied all deaths over a 2-year period in New Zealand and of a total of 2122 deaths during the study period, 348 cases (16%) were assessed as potentially having required palliative care, giving a rate of 1.14 per 10,000 children per year. Thirty seven per cent of these deaths were due to cancer, 24% congenital anomalies, 11% cardiac

P.10

conditions, and 28% other conditions. Twenty-nine per cent of these children died in hospital [69].

In the United States approximately 55,000 children aged 0 19 years died in 1999. Seventy per cent of these deaths are from illnesses but data is not available for assessing how many of these might have benefited from palliative care [70].

Dastgiri [71] studied infants born with congenital anomalies and found that 12% had died by the age of 5 years. Death secondary to chromosomal abnormalities was approximately 50% by 5 years.

Cancer in children differs from cancer in adults. Leukaemias account for 30%, brain tumours 20%, lymphomas 10%, and neuroblastomas for 8% of all new child cancer cases. Cancer incidence has remained relatively constant over time. In Canada, the incidence of cancer derived from mortality data between 1984 until 1994 was 14.7 per 100,000 children per year. The crude average annual incidence of cancer in Australian children under the age of 15 years was 13.8 per 100,000 [72]. These rates are 20 30% higher than those of most developing countries, which are lower, for reasons of both higher mortality from acute conditions and under-recognition. Any variation in international cancer rates reflects differences in case ascertainment as well as genetic susceptibility and environmental exposure to carcinogens; HIV exposure is likely to increase the numbers of people with Kaposi's sarcoma and lymphoma.

Estimation of incidence from hospital-based studies

If all children with a life-threatening condition died in hospital, studies based on hospital admissions/deaths would be a good proxy for the incidence of death in these conditions. However, increasingly children are dying at home, for example, an increase from 21% to 43% over the period from 1980 to 1998, especially in more affluent areas in developed countries [73, 74]. Also conditions surviving into adulthood would be under-represented, as would children who died unexpectedly at home or died in hospitals remote from their local hospital. Determining population denominators for hospital-based studies is also often problematic because specialist children's hospitals are often remote from the place of residence of the children.

Prevalence of life-threatening conditions in the United Kingdom

Prevalence is very dependent on definition of a life-threatening condition some studies are limited to those children who died in childhood, some exclude malignancies while others do not clearly state the population studied. Estimates of prevalence can either be derived from use of services, or specially designed population surveys. In addition communities where there is a high incidence of intra-familial marriage have a greater prevalence of recessive genetic disorders, and therefore local figures need to be derived taking account of conditions specific to ethnic minority groups and local populations.

Some examples include:

A local Chichester (UK) evaluation by Wallace and Jackson [18] identified children with life-threatening conditions from a district-wide special needs register and estimated a prevalence of 8.57 per 10,000 in 0 16 year olds.

Nash [75] estimated a prevalence of 10 per 10,000 children in Cornwall, excluding malignancies.

A National Health Service Executive review of a number of Department of Health funded local projects for children with life-limiting conditions (all causes) suggested a prevalence of 10 13 children per 10,000 population, but no age range was specified [76].

A population-based survey by Lenton et al. [77] in Bath (UK) suggested a prevalence of non-malignant life-threatening illness to be 1.28 per 1000, while simultaneously the prevalence of malignant disease was 0.65 per 1000 children aged 0 19 years. This study excluded children in hospital with acute conditions either in the neonatal period or secondary to acute illness or injury. Mental health diagnoses which were life-threatening were also excluded.

ACT reviewing the UK data suggests that there are at least 12 per 10,000 children with life-limiting conditions in need of palliative care. [36]

The Association of Children's Hospices (ACH) in the UK estimates that the number of children actively using hospice services is currently 3000 per annum. The growth in numbers of hospices catering for children may increase demand to 4000 4500 children in the next 5 years [78].

Non-malignant life-threatening disease profile

The Bath (UK) study indicates that cystic fibrosis is the commonest single diagnosis, but neurological conditions as a group are the commonest case of premature death [77]. The authors acknowledge that children with severe disabilities, mainly severe learning difficulties associated with cerebral palsy, are probably underestimated as clinicians rarely perceive or label them as life-threatening during early childhood (see Table 1.2).

Associated morbidity

Assessment of associated morbidity is difficult, largely because of the wide range of impairments, and absence of a clinically relevant assessment scale that is applicable to all types of disability. The Bath (UK) study assesses functioning derived

P.11

Table 1.2 Diagnostic groups of children with non-malignant life-threatening disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

from a British Association for Community Child Health publication [79]. The impact on everyday activities was assessed according to whether additional help was required. The results of this UK study also indicated high levels of psychological distress, significant effects upon employment and relationships, and a family environment characterised by low expressiveness, cohesion, and high conflict. Differences between mothers and fathers were found on a number of variables, for example, 53.8% of mothers and 30.0% of fathers were identified by the General Health Questionnaire [80] as having significant mental health problems. Length of time since diagnosis, level of family cohesion, and sex of parent, significantly predicted parental mental health status [81]. Almost 24% of healthy siblings were identified by the Rutter Questionnaire (1970) as having some degree of emotional or behavioural problems. A finding confirmed in a review of the literature by Williams et al. [82] in studies of siblings of a child with a chronic illness, where the majority (60%) were negatively affected, for 30% there was no impact, and in 10% there was improved functioning.

Summary

In developed countries, children requiring palliative care fall into two groups, those with malignant conditions and those with non-malignant conditions. The majority of malignant conditions are now curable, though a significant minority will have a terminal phase requiring palliative care. In contrast, the majority of non-malignant conditions are not curable. Non-malignant conditions fall into two groups those with neurological conditions where there is a profound impact on everyday living through severe learning difficulty or impaired sensory/motor skills, and those without neurological conditions who often have intensive therapy regimes (for example, cystic fibrosis, renal dialysis, or cardiac disorders) to maintain life. Both groups of conditions impact on quality of life for the child and his/her family in different ways.

The best estimate of prevalence, allowing for methodological flaws, under-ascertainment, and likely trends, is 1.5/1000 children and young people from birth to 19 years likely to die prematurely from non-malignant life-threatening conditions. The annual incidence of death from these conditions is 1:10,000 and slowly decreasing over time.

References

1. Sahler, O.J.Z. (ed.) The Child and Death. St Louis: CVB Mosby, 1978.

2. Chapman, J.A. and Goodall, J. Dying children need help too. BMJ, 1979;1:593 4.

P.12

3. Chapman, J.A. and Goodall, J. Helping a child to live whilst dying. Lancet 1980; April 5:753 6.

4. Corr, C.A. and Corr, D.M. (eds.) Hospice Approaches to Paediatric Care. New York: Springer, 1985.

5. Corr, C.A. and Corr, D.M. Paediatric hospice care. Pediatics 1985; 76:774 80.

6. Lauer, N.E., Mulhern, R.K., Hoffmann, R.G., and Camitta, B.M. Utilisation of hospice/home care in paediatric oncology. Cancer Nurs 1986;9(3):102 7.

7. Dominica, F. The role of the hospice for the dying child. Br J Hospital Med. 1987;October:334 43.

8. Baum, J.D., Dominica, F., and Woodward, R.N. Listen My Child has a Lot of Living to do. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

9. Worswick, J. A House called Helen. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

10. Sligh, J.S. An early model of care. In A. Armstrong-Daley, S.Z. Goltzer, eds. Hospice Care for Children. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, pp. 219 30.

11. Grebin, B. Palliative care in an in-patient hospital setting. In A. Armstrong-Daley and S. Zarbock, eds. Hospice Care for Children (2nd edition). New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 313 22.

12. Martinsen, I.M., Armstrong, G.D., Geis, D.P., Anglim, M.A., Gronseth, E.C., MacInnis, H. et al. Home care for children dying of cancer. Pediatrics 1978;62:106 113.

13. Lauer, M.E., and Camitta, B.M. Home care for dying children: a nursing model. Pediatr 1980;97:1032 5.

14. Goldman, A., Beardsmore, S., and Hunt, J. Palliative care for children with cancer home, hospital or hospice. Arch Dis Child 1990;65:641 3.

15. Curnick, S. Domiciliary nursing care. In J.D. Baum, F. Dominica, and R.N. Woodward, eds. Listen My Child has A Lot of Living To Do. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990, pp. 28 33.

16. Martin, B.B. Home care for terminally ill children and their families. In C.A. Corr and D.M. Corr, eds. Hospice Approaches to Paediatric Care. New York: Springer, 1985, pp. 56 86.

17. Lombardi, N. Palliative care in an in-patient hospital setting. In A. Armstrong-Daley and S.Z. Goltzer, eds. Hospice Care for Children. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, pp. 248 65.

18. Wallace, A. and Jackson, S. Establishing a palliative care team for children. Child Care, Health Dev 1995;21:383 85.

19. Kopecky, E.A., Jacobson, S., Prashant, J., Martin, M., and Coren, G. Review of a home based palliative care programme for children with malignant and non-malignant diseases. J Palliat Care 1997;13(4):28 33.

20. Lewis, M. The lifetime service: a model for children with life-threatening illnesses and their families. Paediatr Nurs 1999; 11(7):21 2.

21. Wilson, D.C. Developing a hospice programme for children. In C.A. Corr, and D.M. Corr, eds. Hospice Approaches to Paediatric Care. New York: Springer, 1985, pp. 5 29.

22. Field, M.J. and Behrman, R.E. (eds.) When children die, improving palliative and end of life care for children and their families. Committee on Palliative and End of Life Care for Children and their Families, Board on Health Sciences Policy. Washington: National Academies Press, 2003, p. 208.

23. Levetown, M. Pediatric care: The in-patient/ICU perspective. In B.R. Ferrel, and N. Coyle, eds. Textbook of Palliative Nursing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 570 81.

24. Catlin, A. and Carter, B. Creation of a neonatal end of life palliative care protocol. J Perinat 2002;22(3):184 95.

25. Craig, F. and Goldman, A. Home management of the dying NICU patient. Semin Neonatal 2003;8(2):177 83.

26. Dominica, F. Helen House a hospice for children. Mat Child Health 1982;7:355 9.

27. Burne, S.R., Dominica, F., and Baum, J.D. Helen House a hospice for children: Analysis of the first year. BMJ 1984;289:1665 8.

28. Editorial. On children dying well. Lancet 1983;April:966.

29. Chambers, T.L. Hospices for children. Editorial, BMJ 1987;294: 1309 10.

30. Moncrieff, M.W. Life-threatening illness and hospice care. Arch Dis Childhood 1990;65:468.

31. Saunders, C. In D. Clark, ed. Cecily Saunders (Letters 1959 1999). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 192.

32. Stein, A. and Woolley, H. An evaluation of hospice care for children. In J.D. Baum, F. Dominica, and R.N. Woodward, eds. Listen My Child Has a Lot of Living to Do. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990, pp. 66 90.

33. Davies, B., Collins, J.B., Steele, R., Pipke, I., and Cook, K. The impact on families of a children's hospice programme. J Palliat Care 2003; 19(1):15 26.

34. Robinson, C. and Jackson, P. Children's Hospices. A Lifeline for Families? National Children's Bureau. London 1999.

35. Sheldon, F. and Speck, P. Children's hospices: organisational and staff issues. Palliat Med 2002;16:79 80.

36. A guide to the development of children's palliative care services. Report of a Joint Working Party of the Association for Children with Life-Threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families (ACT) and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) (2nd edition), 2003, Published ACT.

37. Hynson, J.L., Gillis, J., Collins, J.J., Irving, H., and Trethewie, S.J. The dying child: How is care different. Med J Aust 2003;179(6):S20 22.

38. Finlay, I. and Webb, D. Paediatric palliative care: the role of an adult palliative care service. Palliat Med 1995;9(2):165 6.

39. McKeogh, M.M. and Evans, J.A. Paediatric palliative care: The role of an adult palliative. Palliat Med 1996;10:51 4.

40. National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services. Specialist palliative care: A statement of definitions. National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services. London, 1995.

41. Standing Medical Advisory Committee (SMAC) and Standing Nurse and Midwifery Advisory Committee. The principles and provision of palliative care. Joint Report of SMAC and Standing Nurse and Midwifery Advisory Committee. London, 1992.

42. A guide to the development of children's palliative care services. Joint Working Party of the Association for Children with Life-Threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families (ACT) and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH). London: ACT/RCPCH, 1997.

43. World Health Organization (WHO), WHO Definition of Palliative Care, 1998. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

44. Strauss, D.J., Shavelle, R.N., and Anderson, T.W. Long term survival of children and adolescents after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998i;79:1095 1100.

45. Strauss, D.J. Life expectancy of children with cerebral palsy. Lancet 1988ii;349:283 4.

P.13

46. Grossman, H.J. and Eyman, R.K. Survival estimates of severely disabled children. Paediatr Neurol 1998;19(3):243 4.

47. Hutton, J.L., Cooke, T., and Pharoah, P.O.D. Life expectancy in children with cerebral palsy. BMJ 1994;309:431 5.

48. Doull, I.J. Recent advances in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Childhood 2001;85(1):62 6.

49. Stein, R.E. and Jessop, D.J. What diagnosis does not tell: The case for a non-categorical approach to chronic illness in childhood. Soc Sci Med 1989;29(6):769 78.

50. Kirk, S. and Glendenning, C. Supporting parents caring for a technology dependent child in the community. Research Report, National Primary Care Research and Development Centre, University of Manchester, 1999.

51. Glendenning, C., Kirk, S., Guiffrida, A., and Lawton, D. Technology dependent children in the community: Definitions, numbers and costs. Child Care Health and Dev 2001;27(4):321 24.

52. Stjernsward, J. and Clark, D. Palliative medicine a global perspective. In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, N. Cherney, and K. Calman. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 2003, pp. 1199 1224.

53. Seale, C. Changing patterns of death and dying. Soc Sci Med 2000; 51(6):917 19.

54. Alloo, F., Arizpe, L., et al. Bellagio declaration: Overcoming hunger in the 90s. Lancet 2003;362(9387):915.

55. WHO (World Health Organization). Bridging the gaps. World Health Report. Geneva, WHO, 1995.

56. Anonymous. The world's forgotten children. Lancet 2003i; 361(9351):1.

57. Anonymous. The Bellagio study group on child survival. Knowledge interaction for child survival. Lancet 2003ii;362:323 7.

58. Bryce, J., Arifeen, S., Pariyo, G., and Lanata, C. Reducing childhood mortality: Can public health deliver. Lancet 2003;362(9378):159.

59. Jones, G., Steketee, W., Black, R.W., Bhutta, Z.A., and Morris, S.S. The Bellagio study group on child survival. How many child deaths can we prevent this year. Lancet 2003;362:65 71.

60. Haines, A. and Smith, R. Working together to reduce poverties damage. BMJ 1997;314:529.

61. United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

62. United Nations Annual Human Development Report. http://www.undp.org/hdr2003/

63. Plunkett, M.C.B. and Southall, D.P. War and children. Arch Dis Childhood 1998;78:72 7.

64. UNICEF. The state of the world's children, 2004.

65. Franks, P.J., Salisbury, C., Bosanquet, N., Wilkinson, E.K., Lorentzon, M., Kite, S., et al. The level of need for palliative care: A systematic review of the literature. Palliat Med 2000;14(2):93 104.

66. Horrocks, S., Somerset, M., and Salisbury, C. Do children with non-malignant life-threatening conditions receive effective palliative care? A pragmatic evaluation of a local service. Palliat Med 2002;16(5):410 16.

67. Thornes, R. Working party on the care of dying children and their families: Guidelines from the British Paediatric Association. Birmingham NAHA: King Edward's Hospital Fund for London, 1998.

68. While, A., Citrone, C., and Cornish, J. A study of the needs and provisions of families caring for children with life-limiting incurable disorders. King's College London: Department of Nursing Studies, 1996.

69. Jones, R., Trenholme, A., Horsburgh, M., and Riding, A. The need for paediatric palliative care in New Zealand. N Z Med J 2002;115(1163):U198.

70. Field, M.J., and Behrman, R.E. (eds.) When children die: Improving palliative and end of life care for children and their families. Committee on Palliative and End of Life Care for Children and their Families Board on Health Sciences Policy. Washington: National Academies Press, 2003.

71. Dastgiri, S., Gilmour, W.H., and Stone, D.H. Survival of children born with congenital anomalies. Arch Dis Childhood 2003;88:391 4.

72. McWhirter, W.R., Dobson, C., Ring, I. Childhood cancer incidence in Australia. Int J Cancer 1996;65:34 8.

73. Feudtner, C., Silveira, M.J., and Christakis, D.A. Where do children with complex chronic conditions die? Patterns in Washington State 1980 1998. Pediatrics 2000;109(4):656 60.

74. Higginson, I.J. Children and young people who die from cancer: Epidemiology and place of death in England. BMJ 2003;327 (7413):478 9.

75. Nash, T. Summary report and recommendations of Department of Health Funded project for children's hospice South West. Development of a model of care for children suffering from life-limiting illness other than cancer and leukaemia and their families in the South West. University of Exeter, 1998.

76. National Health Service Executive Review of Department of Health Funded Projects for Children with Life-limiting Conditions, 1998.

77. Lenton, S., Stallard, P., Lewis, M., and Mastroyannopoulou, K. Prevalence of non-malignant life-threatening illness. Child: Care Health and Dev 2001;27(5):389 97.

78. ACH (2001) Joint briefing Palliative Care for Children www.childhospice.org.UK/download/paediatricleaflet.pdf.

79. British Association for Community Child Health. Disability on childhood: Towards nationally useful definitions. British Paediatric Association, London.

80. Goldberg, D. The manual of the general health questionnaire. Windsor: Berks, 1978.

81. Mastroyannopoulou, K., Stallard, P., Lewis, M., and Lenton, S. The effects of childhood non-malignant life-threatening illness on parent health and family function. J Child Psychol Psychiatr, 1997; 38(7):823 9.

82. Williams, P.D. Siblings and paediatric chronic illness: A review of the literature. Int J Nurs Studies 1997;34(4):312 23.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 47