15 - Bereavement

Editors: Goldman, Ann; Hain, Richard; Liben, Stephen

Title: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children, 1st Edition

Copyright 2006 Oxford University Press, 2006 (Chapter 34: Danai Papadatou)

> Table of Contents > Section 2 - Child and family care > 13 - Impact of life-limiting illness on the family

function show_scrollbar() {}

13

Impact of life-limiting illness on the family

Mary Lewis

Helen Prescott

Introduction

When a child is diagnosed with a life-threatening condition, a family is cast into a world it probably did not even know existed. A world full of confusion, disbelief and anguish unfurls, wheredifficult decisions regarding care and treatment and the desperate need for hope will have to be balanced with the realism of diagnosis.

Being a parent of a child like Kim is like going to another planet; there isn't a guide book'. (Julia, Kimberley's Mum)

This chapter introduces the reader to some information about the family living with a child with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness, and the impact on individual members within the family. In the first section, the notion of family is defined, and family functioning and roles are discussed. In the second section, the effects of long-term illness, dying and death of a child on individuals within a family are introduced. In the final section, the reader is acquainted with some strategies and suggestions on how professionals and services can work with families to offer effective and timely support and help.

It is our argument that a long-term family care model which incorporates an understanding of individuals' and systems' roles, their needs and their beliefs to ensure optimum quality of life, is required. This approach is in accord with the values and philosophy required for care within the context of contemporary society. It has been noted in the literature on families [1] that some authors focus upon individuals, and regard other members as the social context of the person, whilst others look at the family unit as a whole, with individual familymembers making up parts of the whole. In this chapter we hope to develop readers' thinking and practice beyond the current tendency towards individual focus [2], to caring for the family as a unit, although not at the expense of individuals.

We have also included parents' narratives with the aim of adding depth and lending coherence to the discussion [3]. This approach is in keeping with the contemporaryhealth care policy in the United Kingdom of user involvement [4, 5, 6]. Our acknowledgement and thanks go to all the families who have contributed so unreservedly with this endeavour.

The experience of conditions and long-term illnesses that are palliative encompasses two emerging concepts: a life span developmental perspective and quality of life. We believe these are keys to an understanding of the experiences of families, and of how to help them.

Life span perspective

A family, when a child member has a life-threatening or life-limiting illness, faces a series of biographical disruptions [7] and transitions to differing levels of adversity [8, 9]. In an exploration of the meaning of health for adults with Cystic Fibrosis [7], health is suggested as a dynamic concept [9].

Laurence's narrative illustrates this.

Case

We are on a long journey that is constantly changing; our journey has changed and our needs have changed, and we see now will continue to change. We have therefore needed services and people to adapt and change as time goes by in a non-prescriptive way. In the beginning we needed dailyvisits, both to help with Alice's care and to support and keep us going. Two years on and we need regular contact, not so regular visits and support to organise a family trip to Euro Disney, including a care plan in French.' (Laurence: Katy, Oliver, Alice and Isobel's dad)

P.155

A life-span perspective reflects health as a dynamic concept, and incorporates the formation ofhealth beliefs and habits during the developmental years of childhood and adolescence, [10, p. 476] alongside a family unit's evolving experience of caring for a child with a life-threateningor life-limiting illness. This allows periods of both change and stability to be viewed in a social context [7, 10].

Quality of life

Quality of life is an emerging and central concept [3, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] relevant to this group of families. Meaningful measures of quality of life should be used to evaluate health and social care interventions [16]: symptom response and survival rates are no longer enough'. Definitions and measurements of the notion of quality of life, however, are inconsistent, making meaningful comparisons difficult [17]. The validity of health professionals' specific attempts to influence quality of life has been questioned [18]. It is rather suggested that health is one of many constituents, and its relative importance changes at different levels over a life span [18, 19]. An alternative approach may be the use of lay definitions [17] to understand quality of life from an individual's perspective, [3] and place an emphasis on listening very carefully to personal perceptions of family members about quality-of-life issues.

Definitions of the family

A review of the literature on family theories and methods suggests that researchers from a variety of disciplines have struggled to define the term family [20]. Baggaley [2] points out that when family is used in thecourse of social interaction, it is readily understood by others. However, if we take time to consider what might be a definition of a family, the potential for different interpretations becomes apparent. Families do not exist in a social vacuum, but are partly determined by the surrounding culture. Skynner [2, p. 27] considered the family to be both inward- and outward looking and emphasised that society both reflects change in families and that society effects change upon families over time. This mutuality means there are as many forms of families as there are societies' [2, p. 27].

The Oxford dictionary's definition of family is a household ; although household fits with the census definition of family, it does not take account of the notion of family relationships. In the context of family nursing, Wright and Leahey [21, p. 40] use the following definition: the family is who they say they are'. This appears to accord with Frude's [1] notion of selection criteria, that involves an individual stating whohe/she regards as being a member of the family, involving feelings of affinity, obligation, intimacy and emotional attachment' [1, p. 4].

The advantage of this approach is the recognition of non-traditional family groupings that are a feature of contemporary society [22]. Examples include single parent households, cohabiting couples, homosexual couples and any variation that may be encountered when working with families from cultures other than that of the host country' [23, p. 7].

The approach suggested, therefore, is an acceptance of the family's own definition of itself that provides a way of recognising the importance of affectional bonds [22] which do not precisely fit with the conventional view of the family, but equally, do not devalue the strength of the traditional family.

Family systems

The traditional view of family involvement in health care has been uni-dimensional, with family either helping or hindering patient health [24, 25]. A family system approach moves the focus away from individuals to their primary social context, the family system [10, 24], and the notion of family-centred care in the direction of family health. In the reality of practice, it is recognised that the shift in focus from family as context to family as unit of care may vary in relation to episodes in the family's experience [23]. However, we believe that this change of focus is timely and relevant to contemporary health and social care. This approach hasits roots within the systems theory, and a brief discussion follows to put this into context.

The systems theory provides a basis for models of adaptation, for example, of families, and supports both empirical and theoretical perspectives [26]. In systems theory, all levels are linked within a hierarchical continuum, linking larger subordinate units to less complex ones. This provides a focus on accommodation, through the life span, between the individual and his/her changing environment. In the context of life-threatening and life-limiting illness, this approach suggests a need to explore the multiple factors that affect outcomes, as well as a need to assess the impact on individuals, families and communities of these diagnoses. It also suggests the notion of continuous interaction of both constitutional and environmental factors over time[26]. A systems developmental perspective offers a framework for interdependence between the properties of the person and of the environment, the structures of the environmental settings and the processes taking place within and between them' [27].

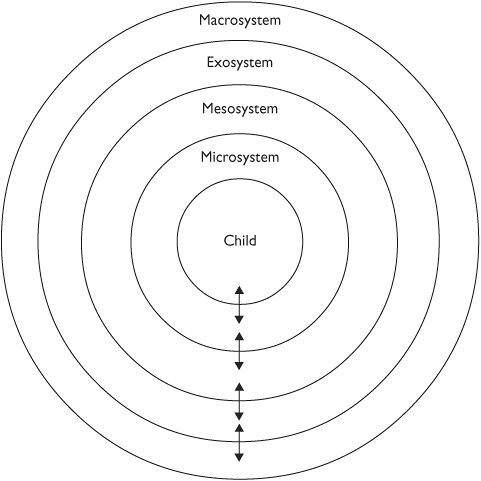

Four levels of systems in society are described, which relate to individuals with long-term illnesses, and to family systems [10, 26, 27, 28] (Table 13.1 and Figure 13.1).

Within this model reciprocity, interconnections and relations between settings, transitions and role shifts are central

P.156

across the life span of a child and his illness journey [26]. There is much evidence now of the impact of parents' child-rearing behaviour on children's development. The systems theory identifies the crucial role of parenting as one of the adaptations that occur through the life span between a child and his or her environment. Life-threatening and life-limiting illnesses present a substantial challenge to the adaptation process, representing a major stressor to which the child and family systems endeavour to adapt.

Table 13.1 Four levels relating to family systems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Fig.13.1 Diagram representing the family systems framework. (Adapted from Thompson and Gustafson [26]; Bronfenbrenner [29]; Wright and Leabey [30].) |

The family is a system in which the sum is more than the total of its parts. Anything that affects the system as a whole will affect the individual members, while anything that affects the individual members will necessarily affect the system as a whole. Like all systems, the family system struggles to maintain its balance and equilibrium. Bluebond-Langner's [31] ethnography of well siblings of children with cystic fibrosis illustrates how chronic illness sets the family and its members apart from others, and creates challenges for individuals and relationships within families.

Plans, roles, duties, obligations and priorities change as family life is interrupted bythe burdens of care and treatment' [12, p. 200].

It is suggested that this way of conceptualising the effects on family functioning takes account of the dynamic processes involved, and incorporates social and psychological elements [10, 26]. Although strategies are adopted that enable familymembers to live with some sense of normalcy and control, it is not suggested that these strategiesremove the conflicts or pain of the illness [31]. No more than all physical illnesses can be cured, can all social and psychological problems be prevented or remedied ' [31]. This is an important concept when assessing the outcomes and potentiality of the notion of professional support for families and family members.

Families develop specific roles, rules, communication patterns, expectations and patterns of behaviour that reflect their beliefs, values, norms, coping strategies, system alliances and coalitions to keep the system as consistent and stable as possible. A life-threatening or life-limiting condition is a diagnosis that affects the whole family, and the responses of the child, parents andsiblings are highly interdependent. Laurence's narrative illustrates this.

When our first child, Isobel, died at 9 months of age and when two days later we knew her twin, Alice, had the same unknown but life-threatening illness, our journey began and has affected our whole family. We were lost, totally confused; had lost control over everything we were doing. We have all adapted to accommodate Alice's needs. It has been very traumatic; there is no consolable or reasonable explanation for this happening to us. But we would like to think we are better people for it. As a family we are very close, we share a common experience and all know that Alice is special. She is a child who brings drama and extreme emotions to our lives.'(Laurence: Katy, Oliver, Alice and Isobel's dad)

Although the focus of this chapter is the family, it is recognised that a balance must be foundin acknowledgement of Friedemann's [32, p. 15] suggestion that if the whole family system is viewed as the person who receives the care, the focus on each individual in the family is lost'. In order for the family as a whole to be balanced, the health and well-being of the individuals needs to be both understood and maintained as far as is possible. This concords with Mackenzie's [33] view that to provide support, (nurses) need to beable to see into the

P.157

heart of each family and understand the experience from its perspective' [33, p. 82]. This needs to be balanced with the requirement to consider the welfare of the child, child protection [34] and the rights of the child.

The next section provides a brief overview of roles within a family before reviewing the impacton individual family members of life-threatening and life-limiting illness.

Roles within the family

Family members occupy a specific position, or status, within the family that of mother, father, brother or sister. The conceptualisation of these roles in families has evolved and changedwith the evolution of the family and contemporary society. For example, in Western society, fathers have tended to become more involved in the care of children, and mothers may continue with theircareers. For each role within a family's culture, there is a prescription of appropriate relationships and behaviour that influences daily life. Role theory espouses that family roles are reciprocal and directly relate to other roles in the family [35]. Existing family relationships and dynamics are well established, and need to be discovered [36] in order to enable successful work with families (Box 13.1).

Box 13.1 Roles and patterns within families

Examples of patterns a family may have adopted

-

One parent may be less able to face stress than the other and choose to avoid situations or accept responsibility (for example, avoiding helping with caring for ill child).

-

Parental relationship may be based on one partner being treated as a child by the other partner, and so, unused to being a supportive person within the relationship.

-

Parents may be over-protective of their children.

-

One child in the family may have a very close relationship with another family member, causing feelings of exclusion in the others.

-

Parents may have an existing poor or difficult relationship with the child who becomes ill.

-

One parent may seek support from his or her own parents or friends, rather than his or her partner.

-

The marital relationship may be unsatisfactory, with poor communication and low levels of mutual support.

(Adapted from [Trapp 36, p. 78])

When a child as a family member becomes unwell, the role pattern changes, and the family members have to work out differing role patterns [35]. During this process of reallocation and reorganization of family roles, siblings' and parents' personal and social development may be affected. Families are dealing with a number of concurrent stressors at this time, some linked to the illness and others independent of it, for example, existing financial pressures. The diagnosis has far reaching implications for daily routines, hopes and ambitions [37].

When faced with a diagnosis of a life-threatening condition, family members, particularly mothers, become carers in addition to their existing roles. Innovations in medical practice, advances in technology, and government policy emphasising the community and primary care sectors as the arenas for long-term care [4, 34, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42] have led to children with long-term care needs being cared for in the community, rather than in institutional settings. This is evident in the growth of hospital-at-home schemes, palliative care services and other domiciliary services, including the role of education and social services [43, 44, 45, 46]. Together, these factors have resulted in growing numbers of children being able to live at home, while dependent on their families and medical technology [47, 48, 49, 50]. The family, and more specifically the parents, take on the burden and responsibility of the care of the child, [51] and in many cases, provide highly technical and intensive care that previously has been the domain of professionals [52].

The responsibility of being a parent to two well children is huge; the responsibility ofcaring for an ill child has been unnerving and we have needed time and space to come to terms witheverything.'(Laurence, father)

Parents can often take on the dual roles of co-ordinating care: finding the appropriate professional support whilst at the same time, caring for their child and being parents. In addition, theymay also have to provide emotional support for the rest of the family system.

The loss of existing relationships within a family unit can be very difficult, and places a burden on individuals. A sibling, for example, not only experiences the loss of his or her relationship with the ill child, but also is in an environment where the parents' role is changing to one of caring for an ill child. Families need to be enabled and supported in making the right decisions and choices for themselves that they can be comfortable with in the future [36]. Before trying to bring about change when working with families, it is necessary to gain an understanding of how they work and communicate, and to assess whether any change is actually necessary.

P.158

Cultural and ethnic variables

The impact of culture and ethnicity on individual and family coping and functioning, and the various role expectations of individual family members and the extended family [53] cannot be underestimated. An understanding of the impact of culture and cultural diversityis essential in order to establish and develop effective and safe practice within health and social care. Many health care practices in the United Kingdom, for example, reflect the traditions of British society and its underpinnings of Christianity. Alongside unfamiliar organisational and health care practices, this can cause distress for families from ethnic minorities when they are most in need of support [54]. There is a requirement to elicit families' models of beliefs about the illness, its meaning for them, their expectations and their needs [55]. As with birth, death and dying are perceived as bio-social events, impacting spiritually as well as being physiological processes.

Pickett [55] defines culture as the values, norms, beliefs and practices of a particular group that are learned from generation, to generation, and share and guide thinking, decisions and actions in a patterned way'. A second variant, suggested by Kuper [56], is that the teaching of how to behave and act distinguishes differentpopulations from one another. This may relate to, for example, religion, marriage practices, language and the care of sick and disabled people. Anthropological studies indicate that the key concepts listed in Table 13.2 are not necessarily held in the same way by all cultures [56]. However, there are few studies that focus on the impact of culture on the care of children with palliative care needs and their families.

This area is challenging and complex on a number of levels. While it is recognised that all societies have culture, and belonging to a culture can give a sense of identity and belonging, the juxtaposition is that culture can also be excluding, marking out differences amongst individuals [56]. It cannot be assumed that families from a particular cultural background share the same values, norms and beliefs. Within one family unit, principles affecting decision-making may differ, particularly if members have been influenced by exposure to other cultural traditions. Additionally, just as a life span is dynamic and changing, it cannot be assumed that a cultural perspective is static or unchanging.

Table 13.2 Key concepts that reflect cultural diversity [56] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hall et al. [55] acknowledges that ethnic groups and different cultures may have varying perspectives about ill children and their care. These views may differ from that of the professional care provider, and make the processes of assessment, intervention and evaluation complex. Professionals will need to compare their own framework with that of the family, and develop a shared model that ensures that what is important for the child and the family is central.

We will now introduce a number of examples of the dilemmas that arise when trying to work in a culturally competent way with families that can be challenging.

Challenges for practice

Some illnesses may already hold a cultural context, due, for example, to the high incidence of a condition in one population. The Human Immuno Deficiency virus (HIV) in the African population is an example of this. Individual differences that may be apparent include the personal and social meaning of the illness, expectations of the illness and treatment and expectations of the role of health workers.

Case

A family of Bangaladeshi origin that had recently moved to the United Kingdom was perceived by the hospital care team to be unco-operative and disinterested in learning about their child'scare needs prior to the child being discharged. With the aid of an independent translator, it became apparent that the family members were not aware of the expectation that they would participate and take on their child's care, within their own tradition, this would not have been a parental role.

Once this understanding had been achieved, the family was both able and willing to fully learn about the child's care, and could take her home with appropriate support.

The way a family reacts to a diagnosis of life-threatening illness in a child member and the way meaning and value to such an event is accorded varies widely across cultures, and it is important to accommodate the wishes of the child and his or her family at all stages of the child's illness by understanding this.

Each culture attributes a unique significance to the death of a child. Each holds various beliefs about where children come from before they are born, and where they will go to after they die'. [57, p. 92].

The following are a few examples of the differing values and needs, of families during the course of a child's illness, that significantly impact on the care and support they will want andneed.

-

In Western society, a child is a source of meaning and purpose in the parents' lives. The death of a child, consequently,

P.159

is particularly threatening to a parent's identity as a protector and provider, and can lead to a sense of failure. -

Egyptian mothers are expected to be withdrawn, mute and inactive for seven years after the death of a child; this behaviour is normal by their cultural standards. In contrast, a Western mother is expected to grieve in private, and return to normal activities soon.

-

In some cultures, gender differences affect reactions. For example, if a male child is diagnosed, this will be more traumatic than a female child being diagnosed for a family whose expectation culturally is that he will perpetuate the family name, and be a provider as an adult.

-

A variety of traditions relating to preparation for death and for arrangements afterwards exist, and it may be that the rituals that are followed for adults differ from those for children. For example, the Greeks dress a child who has died in wedding attire, as death before marriage is perceived to be especially traumatic. In the Chinese tradition, the death of a child is seen as bad and family members do not attend the funeral or discuss the death, as it is consideredshameful to the family [57].

-

Infant deaths (and illnesses) may be afforded a special status, with abbreviated rites of bereavement, probably linked with low expectation of survival in some populations. For example, in West Africa, the death of a child under one year of age is seen as a minor loss, and is disregarded by society, and sometimes, the parents themselves. Hindu infants are buried, not cremated, as they are expected to return to earthly life.

-

In societies influenced by Western medicine, hospitals have become the focus of care, with professionals delivering this care [57] and attempting to prolong life througha series of interventions. In other societies, care of the dying is still seen as the responsibility of the family and community, and the focus will be on the home.

Within any society, the needs of a cultural minority are generally inadequately met by health and social care services. There is a low uptake of palliative care services by ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom, for example [55]. This is a matter of concern, as it may lead to culturally diverse perspectives being ignored, and to culturally insensitive decisions and health policies, especially where systems are located within a Western tradition. The difficulties lie beyond barriers relating to language differences, in barriers created by ethnocentric beliefs professionals may hold, that need to be overcome.

In a study of a South Asian population living in the United Kingdom, Randhawa et al. [58] found that among the reasons for poor uptake of services were lack of knowledge about service availability and communication difficulties between families and service providers. This would suggest the need for services, and professionals working in them, to develop what Randhawa et al. [58] call cultural competence . To take the example of communication differences, however, the problem is not easily resolved using translators, due to the inavailability of personnel with the appropriate knowledge or skills. Family members, notably child members, are relied on, and this can cause difficulties, particularly when sensitive, distressing, and at times, personal information needs to be conveyed. The use of children as interpreters has been said to be unprofessional, unethical, uncivilised and totally unacceptable [58]), but may be the only option available in some circumstances. We would suggest that it is important, in establishing communication to understand the significance of gender and language, for example, and to develop an understanding of the perceptions, knowledge and attitude of the family. This is worth striving for, as good communication lies at the heart of a culturally competent model of palliative care [59].

In concluding this section, we would reinforce the importance of developing an understanding of the interpretation of life-threatening illnesses with culturally diverse families, and their approaches to the care of ill children. We would suggest that this is imperative to reduce stigma and social distancing between providers and recipients of palliative care.

Effects of illness, dying and death of a child on the family

We will now focus on a consideration of the impact of illness, dying and death on family members. As has been noted, the reactions of individuals affect the family system as a whole, and maintaining equilibrium requires both understanding and finding ways of supporting both individuals and the family unit as a whole.

Parents

The course and treatment for a child with a life-threatening illness varies under different conditions, and with different children. Many aspects of the experience of the illness, however, are determined not so much by the particular illness as by developmental, family and social issues. Continuous adaptation occurs at all points on the illness trajectory, the timescale of which varies greatly according to the child's underlying disease process. The families' adaptation will be influenced by both internal and external factors that are influencing the family systems at any one point in time. Parents move through

P.160

a series of changing biographical disruptions, moving from diagnosis, to coming to terms with, and living with, the illness, to when death is imminent, to when the child dies. At each of these phases, parents and other family members experience a series of losses. Loss can be actual, potential or anticipated. However, since each individual has a unique relationship with the ill child, different things will constitute loss to him or her. This needs to be recognised on an ongoing basis, as the nature and effect of the loss for individuals in the family will directly affect their emotional well-being and ability to adapt and cope with each phase of the child's life.

Diagnosis

There is no easy way for parents to learn that their child is seriously ill. Their sense of shock, numbness and disbelief is much like the experience of bereavement, of mourning for the loss of the healthy child they had known or hoped for. Denial, anger, guilt and despair in varying degrees may all play a part in this initial period. A sense of isolation and loneliness may also be experienced. For some parents, diagnosis may come as confirmation of fears they have harboured for some time, and for some of these parents, the certainty of diagnosis can be a relief. Families have been found to employ a number of different coping strategies at this time [54]. Some enter a period of mourning, while others adopt a proactive caring role [54] and yet others begin a quest for information [60].

It is well recognised that the manner in which news of a life-threatening diagnosis is given to a family is very important. There is some acceptance that in reality, this is often done in a less than satisfactory way [40], with recipients perceiving an uncaring and insensitive response from the professional involved. This can have a major and long-term adverse impact on recipients, affecting adaptation and coping (Fallowfield 1993 in [61]) and trust in the care team [54]. Parents have difficulty absorbing information, and incorrect assumptions can be made relating to parental understanding. If presented poorly, parents will recall the distress and remain angry for many years, as the following narrative illustrates .

The appointment at which we were told about our son, Edward's devastating diagnosis and prognosis was in itself a traumatic experience which because of the way it was conducted by the Consultant Neurologist, has continued to haunt and scare us over seven years on.

We feel it was handled badly for the following reasons:

-

The consultant never once said he was sorry or saddened by the news he was giving us.

-

His triumphalism' at correctly diagnosing Edward's rare diagnosis (Adrenoleukodystrophy) was all too evident.

-

When we asked for information he suggested we go away and find out about it and suggested we watched the film Lorenzo's Oil .

-

When we asked about support available he did not offer to find out on our behalf, even though we now know there was a local service for children with life-threatening and life-limiting illnesses.

This experience left us traumatised, very frightened, bewildered and with an overwhelming feeling of being abandoned.' (Helen and Keith, Edward's parents)

In the United Kingdom, there has been a focus on educating and supporting physicians to improve their skills in breaking bad news. However, handling information-giving and early contact with family members need to be done well by all professionals [61], and education in this area should have a multi-professional and collaborative focus.

A key concept for those involved is the recognition of the uniqueness of the event for the individual family receiving the news. Even though the professional may have delivered similar news to a number of families, each individual situation must convey and reflect an essence of caring that is unique [61]. Good interpersonal skills are a central requirement, and a number of attributes are reported to be important in the person delivering the news. Examples include honesty, frankness, gentleness, sympathy and empathy. Box 13.2 suggests other strategies that may be helpful in supporting effective practice in difficult conversations (see also Chapter 3, Communication). A central concept is to remember the significance of this time for the family, as the following narrative illustrates:

Every word said is in my mind, I can remember the smell of the room; I won't ever forget' (mother of child with a cardiac condition).

It is recognized that this is very challenging, especially if a diagnosis, and therefore, prognosis, remains in doubt. In this situation, we would suggest that there is a need to acknowledge what is unknown. However, even this should be communicated sensitively, and as much information as possible should be given. Ongoing management and support of the child and family should not be affected.

Living with the illness

Mastroyannopoulou et al. [62], in a study of 93 mothers and 73 fathers of children with life-limiting conditions, found that overall, mothers and fathers coped very differently. Mothers were more likely to cope through emotional release, whereas fathers coped through withdrawal and by being practical. However, these styles of coping were not always perceived to be as effective by the parents themselves.

P.161

Box 13.2 Strategies for difficult conversations

Planning

-

Respectful and clear communication

-

Time, place and a way of delivering the news agreed upon

-

Availability of professional or friend for afterwards

-

Significant family members present

-

Translator available

-

Private, quiet, and comfortable setting

-

All have enough available time

The conversation

-

Tape the conversation, and give a copy to family

-

Indicate initially that the news is not good

-

Listen very carefully

-

Ascertain existing family knowledge and concerns

-

Use non-jargonistic language

-

Provide diagrams, notes, and information for family to keep

-

Avoid evasions while realizing the family will have a need to maintain hope

-

Make short-term follow up arrangements

Lengthy treatment, frequent hospitalization, relapse and progression of the underlying disease and the burden of care increase the risks of parental distress, which can result in detrimental effects on employment and in financial difficulties, in addition to impacting on family functioning.

When she first came home she was ill all the time. She was re-admitted and when she goes back in it is really bad and you think she is going to die It is very, very, frightening.' (Mother of a child requiring home-ventilation).

The grief reactions associated with the initial diagnosis can re-surface with heightened intensity when a child relapses or deteriorates. Parents may, at this time, experience feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, in addition to grief, fear, depression, anger and denial. For a child who has experienced a period of being very well, a change in his or her condition can have the same effects, with uncertainty about the next steps in the child's illness. This period needs to be handled as sensitively as the discussions at the time of the initial diagnosis.

Case

Kimberley had been diagnosed with a complex cardiac condition at birth that her parents were told would be life-limiting. As an infant, she survived a number of life-threatening surgical procedures that were palliative. She then had a number of years of being very well, with minimal contact with health care services, although her underlying prognosis had not altered. When she was 7 years old, she developed severe problems with secondary pulmonary hypertension. Her parents were given a very poor prognosis, with no clear plans about future care, except that she didn't have long to live.

More sensitive handling of information at this time, as well as planning and availability of ongoing support, would have been extremely beneficial to the family's coping and adaptation to what, to them, felt like a new diagnosis.

The family of a child with an inherited condition has additional difficulties. Family members may have feelings of guilt and blame, and they will need genetic counselling and information about prenatal diagnosis in the future. An added loss that may be experienced is the loss of future children, if parents decide to follow genetic counselling advice that might advocate this. The extent of this will be dependent on existing and future plans and ambitions that the parents had.

Mothers are usually the main care-givers for their children and therefore, are often primarily responsible for the daily medication, treatment routines and often complex nursing care. A life-limiting disease can create some very practical demands at a domestic level. Mothers, more than fathers, may feel that the child's illness limits their opportunities to work outside the family home, and that their career choices are compromised, adding to their sense of isolation, and potentially increasing the likelihood of them experiencing emotional problems [63].

The literature which exists to address the mental health of parents with a child with a life-threatening illness, points consistently to the fact that mothers have poorer mental health than mothers of healthy children, for example, in relation to suffering from anxiety and depression [64].

Bailey et al. [65] (1999) compared the needs of mothers and fathers of children with learning difficulties, and found that mothers expressed significantly more need for family and social support. This group of children are likely to be suffering from degenerative conditions, meaning their illness is characterized by a slow and gradual decline over a number of years. Mothers were reported to need support to manage their stress, conflict and aggressiveness when compared to fathers, who needed more practical information. The longevity of this situation indicates an ongoing and increasing burden, which is compounded by a series of losses as the child's physical and/or cognitive abilities gradually decline.

Studies investigating differences in mothers' and fathers' responses to their child's illness, although limited, have found that women generally respond more emotionally (with

P.162

anxiety, depression, concern), when compared to men [66]. In comparing the impact of childhood non-malignant life-threatening illness on parents, Mastroyann et al. [62], found that low cohesion (characterised by commitment, help and support), length of time since diagnosis of less than two years, and being female were significantly more predictive of higher mental health adjustment difficulties.

The child's illness and care needs can have a profound effect on family social activities, either due to the burden of caring and access difficulties, if the condition is disabling, or due to a need to adhere to strict medication routines and hospital admissions, if the child has cancer, for example. Families describe having to lead a divided life , with one parent staying with the ill child, and the other one going to work, or being with the siblings. This places a strain on existing relationships. A family's private world can be difficult to maintain due to the need to have professional involvement, and in some cases, carers in their home to help them with their child's care. This can place further strain on family relationships.

We know we need them (carers) there, but we would much rather we didn't, so sometimes we get angry with them but it's not them actually, it's the reminder that we can't manage without them because of our child's illness' (Mother of a child with complex needs).

Additional burdens for the family come in the form of practical difficulties with, for example, obtaining equipment when it is required, or in having adaptations done to the home to accommodate a child who becomes immobile; a young man with muscular dystrophy would be an example. These difficul-ties and frustrations that families may experience leave them with unmet needs and compromise their ability to care and feel in control of their situation. Another frequently reported source of frustration in our experience is lack of access to adequate or appropriate respite care to enable parents to take a break form caring, and provide them with time for their own personal and social needs.

When death is imminent

At the pre-terminal stage of illness, the inevitability of death dominates family life. However, recognising this stage of a child's life is problematic for a number of reasons. For those children who are undergoing treatment with a hope of cure, such as children with cancer who have relapsed, or a child with a cardiac condition who is in intensive care following a surgical procedure, the transition is more clearly defined. For this group the following description of this phase of their lives may be used: Terminal care begins at the point in an illness trajectory where nothing can be done to arrest the disease process, and the fundamental goal for the patient shifts from recovery to comfort'[54].

This contrasts with the children who have conditions where cure has never been a possibility, such as those with a neurological condition, or a neuromuscular one such as Duchenne Dystrophy, where the focus of care has always been essentially palliative.

For the first group of children, it can be hard to know when to stop intensive treatment. Physicians following Western traditions tend to focus on cure, and can therefore see dying as failure [67]. Families may have an expectation of treatment continuing. Advances in medicine and technology have created increasing expectations in Western society that death does not have to be inevitable, and that a cure will be found eventually. In following this pathway, the care team and family may collude, and the child may not receive the appropriate treatment and palliative support he or she requires [54]. It is not uncommon for family members to have differing opinions on how long to continue with treatment, and there may be differing cultural expectations. A further complicating factor is if the view of the family does not concord with that of the care team. Within this the child's spoken and unspoken preferences can often be unheard.

Case

The family of an Afghanistani child, who as an infant was found to have multiple neurological complications that were not felt by the medical team to be compatible with good quality for her ongoing life, was reluctant to agree to a do not resuscitate policy, as the family members felt that her life and future would be decided by God. They therefore wanted the care team to do everything possible to keep the child alive, as their belief was that if she was not meant to live, it would be God's decision, and not theirs, in agreeing to a DNR policy. The infant's physician's experience was that to try and resuscitate the child would not be in her best interests, and so, he felt unable to agree unreservedly with the father's wishes.

Seeking a resolution in this sort of situation requires sensitive handling and mutual respect, and understanding through good communication.

For the second group of children, the family will have been living with the possibility of death for the whole of the child's life, or since the diagnosis was made. Families report being given a prognosis about when the child is likely to die, for example, before the age of three years. Leading up to this time, the family may go through a period of preparation and anticipation of imminent death. However, if the child lives past this age, as is often the case there is a tendency to view the child's potential for living more positively. Conversely, if the child dies prior to this time, the family may feel that they have missed out on expected time with the child, and that they were not ready for the child's death. Some children in this group may appear to be very stable, but then die unexpectedly. For others, the possibility of technological interventions, such

P.163

as ventilation, introduces another dimension to the dilemmas they face.

Many children in both groups live lives that are characterised by multiple relapses, but they may confound both parents and professionals by recovering. Each relapse or serious deterioration can then be viewed as survival, and it can be hard for family members to reconcile this with the actual prognosis, and eventual death. It can also mean prolonged periods where the family members are, as one mother described it, living on a knife edge , with great uncertainty over long periods of time.

Case

The parents of a boy with complex and multiple problems understood from the paediatric team that he had only a year at the most to live. During the following months, his parents made preparations for his death, including planning his funeral, informing people at school and arranging special trips and outings for him. During the year, he experienced a number of acute life-threatening episodes, but survived them all.

A year later, he has now reached a plateau, is not experiencing so many acute episodes, and is back at school full-time. His parents have now reversed their previous decision that he not be resuscitated, their rationale being that the prognosis they were previously given was wrong and they need to give their son every chance of survival.

A review of the literature [68] indicated that the quality of care offered during the terminal or last phase of a child's life may have a profound effect on the bereaved. Furthermore, Dominica [69] asserts that family involvement is never more important than in the terminal phase. Recognizing this phase and providing appropriate and timely support is vital; however, there is some evidence to suggest that health care staff underestimate the magnitude of the emotional problems that families experience [68]. Additionally, professionals tend to overestimate opportunities that are available for parents and other family members to express their concerns. For example, when there has not been a definable period relating to the end stage, parents report a lack of information about the prognosis, and at times, inappropriate communication from professionals [68]. The concept of professional distancing' has been noted, as death is imminent and must be guarded against.

The amount of time available to a family is significant for them. If the child's illness means he or she will die as an infant, or in a short time following diagnosis, there is much less time for the family to adjust, and there are less opportunities for choices about the care to be made. Parents need clarity and support through the difficult decisions they are facing. Parents may be unwilling or unsure about making preparations for death if they do not yet accept the inevitable, or if they feel that doing this will be wishing the child away . Alternatively, they may view their child's needs from the perspective of living rather than dying, and not be able, or willing, to adjust to an alternative stance.

However, it is our experience that in the time leading up to the child's death, and the death itself, planning care arrangements, with attention to the smallest details, can make a big difference to families, minimising the potential for regret that they may experience in bereavement. This extends the notion of end-of-life planning, it is suggested, beyond resuscitation plans to planning for pre- and post-death activities by all family members [70].

Another key task for the family when death is imminent is planning where the preferred place of death is for the child. It is worth noting that these may differ; for example, an adolescent may prefer to be in hospital, recognizing the burden being at home places on his or her parents, and needing to be slightly independent of his or her family, but the family may want him or her to be at the family home. There is general acceptance that a hospital environment requires the parents to alter their usual parenting roles [71]. Many studies over a number of years have emphasised both the feasibility and the desirability of home as the preferred place for children with cancer [72, 73]. There is increasing evidence of similar advantages for other children and their families, too [38, 45, 74, 75]. However, for parents, siblings, and the ill child, the availability of a choice of place is the key and ideally their options would include home, hospice or the hospital, with appropriate levels of support being available to them in all of these settings. Each family situation will be unique, and a central principle needs to be that whatever decisions a family makes can be changed at any time.

When a child dies

When a child dies (see Chapter 15, Bereavement), the parents have lost their family as they have known it. Although the family will continue after the death, the family system will be changed by the loss of the presence of the deceased child. Given that a basic function of the parent is to preserve the family and protect the child, there is an implicit expectation that the parent will die before the child.

Where the death results from genetic factors, as indicated previously, parents can hold themselves responsible for not producing a healthy child that could survive longer, and may feel deficient and worthless as a result.

One of the most difficult aspects of parental bereavement is that the death of a child strikes both parents at the same time, and confronts each of them with overwhelming loss. Consequently, a parent's most valuable resource is unavailable, as the person to whom either would normally turn for

P.164

support is also deeply involved in grief. The parents, therefore, may experience loss, upon loss and may have to deal with the grief of their partners as well as their own. Since each parent had a separate and individual relationship with the child, different things will constitute losses to each parent after the child has died. This will be specifically pertinent at anniversary points, or when they see their child's peers undertaking activities that their child is no longer part of, for example, taking their exams or leaving school.

Children

Age and developmental stage influence the impact of illness on children in at least two important ways: their understanding of their condition, and their overall development, including physical, emotional and cognitive development.

Young children tend to understand illness in terms that are concrete, global and magical. They often give explanations of illnesses that involve contagion. A significant number may believe illness is in some way a punishment for bad behaviour. Older children understand that illness means that some part of their body is not working properly. Adolescents are able to appreciate that illness results from an interaction of factors inside and outside the body. The developmental tasks appropriate to the age of the child can be most vulnerable to the disruption caused by the phases and progression of an illness, including the medications, treatment and hospitalisations. A pre-school child is busy gaining increasing mastery over his or her own body and environment. He or she becomes increasingly independent, and begins to socialise outside the family, while learning about roles within the family. Repeated admissions and increased dependency on parents and medical staff may pose a threat to these aspects of development.

For ten or more years of their lives, school is the major social and educational setting for children. Many children with a life-threatening condition can miss significant amounts of schooling. They can fall behind academically, and can be separated from their friends. They can find it hard to keep up with activities that require physical exertion, and they may stand out from their peers at a time when being just like everyone else is important.

Adolescence is a period of great change, and its developmental tasks are challenging, even for healthy young people. Serious illness can force adolescents to become emotionally and physically dependent on their parents and medical staff at a time when establishing independence and planning for the future are key tasks within this period of development. The demands of their illness may cut them off from their peers, and their activities may be restricted. Planning can also become difficult when facing an uncertain future.

Adjustment

Psychological adjustment is central in addressing the psychological functioning of children with a chronic disorder. Good adjustment can be defined as behaviour that is age-appropriate, normative, and healthy, and follows a trajectory toward positive adult functioning. Maladjustment is mainly evidenced in behaviour that is inappropriate for the particular age, especially when this behaviour is qualitatively pathological or clinical in nature [76].

Children with chronic disorders constitute a group vulnerable to maladjustment, but this is not the most common outcome [60]. The variability in their responses would indicate considerable individual differences. As a consequence of this, studies have addressed the risk and resistant factors that may explain these individual differences to chronic childhood disorders.

Wallander and Varni [77, 78] proposed a generic model intended to be potentially applicable to a wide range of paediatric chronic physical disorders. Within a theoretical framework on stress and coping, a paediatric chronic physical disorder is conceptualised as an ongoing chronic strain for both the children and their parents. The model does not assume that a chronically ill child represents an adverse event for the family per se. Rather, the primary factor thought to increase the risk of adjustment problems is stress. Stress results from a combination of the medical condition and related functional limitations, as well as from more general causes that occur in everyday life. Adjustment is hypothesised to be influenced by personal, social and coping processes.

Within the Wallander and Varni model of adjustment, risk factors in adjustment include:

-

Disease and disability parameters, including, for example, diagnosis, medical complications, and cognitive functioning;

-

Functional dependence in the activities of daily living;

-

Psycho-social stressors disability related problems, major life events, and daily hassles.

Resistance factors are defined as:

-

Intrapersonal factors, such as competence, temperament and problem-solving ability;

-

Social-ecological factors, such as family psychological environment, social support, and practical resources available to the family;

-

Stress processing factors, such as cognitive appraisal and coping strategies.

Risk factors therefore elevate the likelihood of adjustment problems, and resistance factors moderate their influence. For

P.165

example, a sibling's emotional ability to cope will depend crucially on the way the family as a whole manages. If a family has previously been dysfunctional (with poor communication, emotional involvement and problem solving), it is likely they will be less able to provide a supportive environment for a sibling to express his or her feelings in. An assessment of family functioning, however, can only be made in the context of family cultural practices.

Case

A 7-year-old boy living with a complex neuromuscular problem since birth had been cared for by his family at home, with relatively minimal support from professionals. His parents and two elder siblings as well as extended family and the local village community provided the majority of the required practical, social and psychological support required.

As his siblings grew up, one was leaving home, and extended family members became unwell, and so, less able to help. The equilibrium of the family system became disrupted, and the family risk factors more significant, until adjustments and increased input from outside agencies could assist the family to address the imbalance and enable it to find new ways of coping very successfully.

Siblings

The devastating impact of a life-threatening/life-limiting condition and childhood death on parents is well recognized, but the effects on siblings are also significant.

But I still get worried about Britt. I just know that with CF (cystic fibrosis) you could die from it. And you get all skinny. And your lungs fill up with mucus. And you can't breathe. And you die'. (Tyler Foster, age 9, talking about his sister, Chapter 12, [12]).

Sibling relationships are complex, extending beyond the traditional notions of rivalry and jealousy [68]. The emotional relationships that children and their families have are dynamic, encompassing rivalry, loyalty, affection and aggression in varying degrees [36, 68]. Children may feel lonely, isolated, sad and displaced in their family. They are surrounded by fear and uncertainty when their established boundaries have changed and are no longer fixed. Children's age, gender, and cognitive and emotional development will differentiate and affect their experience of having an ill child in their family. For example, Wass [28] argues that adolescents, in a sense, are experiencing loss, anyway loss of childhood and the protective support of their parents. The potential death of a sibling at this time, as well as their parents' inevitable distraction, will interfere at every level with their business of being young persons. There will inevitably be conflict and potentially irreconcilable needs.

In a study of 52 healthy siblings of children with life-limiting conditions, Stallard et al. [79] identified significant communication needs in younger children, particularly boys. Despite this, the majority of parents perceived them to be coping well with their sibling's illness. This finding is consistent with that found in other areas of research, including research of siblings children with cancer, and particularly those of post-traumatic stress disorder where adults have been found to repeatedly under estimate the effects of traumatic events on children [80]. The perception of the parents that the child is coping, may be one explanation as to why they are not talking with, or providing more information to their healthy children. Alternatively, parents may be preoccupied with the ill child, and are therefore unable to fully appreciate the needs of the healthy siblings. It is clear, however, that although children do not ask questions, this does not mean that they are not concerned or worried. The reported lack of information provided to younger children may be due to parental uncertainty about what to tell their children, and at what age to do so, or it may reflect a general anxiety about talking with children about painful and distressing events. Whatever the reason, it is clear that parental reports alone must not be relied on to assess the effects on siblings, or to assess what their needs are. Sibling self-reports are very important.

Siblings may have their own versions of the causation of their brother's/sister's illness, and may hold some misconceptions about the nature of the illness, hospital and treatment programmes. They may be fearful of developing the same illness, and alongside this fear, they may experience guilt and relief that they have not developed the illness. They may also experience shame at having a child in the family who is ill or dying. Other feelings about their sick brother or sister include resentment or envy as parents, grandparents and other members of the extended family may be preoccupied with the sick child, [81] which may in turn compromise academic and social functioning [82].

The sick child needs a tremendous amount of parental attention, time and activity, which limits the parents' capacity to attend to and support well siblings.

There is an imbalance with attention and care to other siblings this has an impact. Other siblings get left out.' (Mother of a child requiring home-ventilation).

The demands on the expected roles of parents, such as the mother staying with the sick child in hospital whilst the father cares for the well siblings, or the siblings' stay with other relatives, creates drastic changes in the family dynamics, allowing the well siblings to potentially feel psychologically and emotionally isolated. It is not uncommon, therefore, for siblings to demonstrate difficult and challenging behaviour.

They went to their grandparents when our son was in hospital. It was hard for them.' (Father of a young boy requiring home-ventilation).

P.166

A disturbing feature in siblings that can result from family separation is the manifestation of a number of psychological problems, such as enuresis, separation anxiety, abdominal pain and constipation. A number of behaviours that siblings may display, such as aggression or anti-social behaviour, are assumed to be aimed at gaining parental attention. Murray [83] identifies siblings as: the most emotionally overlooked and sad of all family members during childhood cancer'.

Siblings may also adopt a parental role in responsibility for the other brothers and sisters, and may also participate in the care of their ill brother or sister, or in domestic chores [68].

Some studies, however, report more positive effects of life-threatening illness in siblings [84]. Some siblings appear to benefit emotionally and psychologically from the experience, and are apparently no more at risk of psychological impairment than other siblings. Siblings of disabled children have been found to be more compassionate, sensitive and appreciative of good health than their other peers [68]. Iles [68], in a study of siblings of children with cancer, found that although they experienced the illness as a loss and stressor, they also found it to be potentially a time of growth, with increased empathy for their parents'needs.

It is suggested that there are a number of variables mediating sibling adjustment, but this is an under-researched area Box 13.3.

The wider family: grandparents and others

In discussing the significance for the wider family, it is important to remember that the child and family determine who significant family members are [30, 85] and this may, or may not, include grandparents. It is our experience that grandparents and extended family members can either be a source of support, practical help and strength, or, in contrast, an additional pressure on the nuclear family. A key determinant will be the nature of existing relationships between the grandparents and their adult children, and the grandchildren. These relationships and existing communication patterns will be further influenced by cultural values and beliefs.

Box 13.3 Mediating variables of sibling adjustment

-

Type of disease

-

Type of disability

-

Disease severity

-

Gender

-

Age and age spacing between sibling and the ill child

-

Marital and family relationships

-

Social support

-

Family communication (open or closed)

(Adapted form Drotar and Crawford 1983 in While et al.[68])

The wider family members are involved in the child's life at two levels; firstly, in supporting their adult children through a very painful time, and secondly, in their own grief for the child. From the grandparents' perspective, they are not in a position to have any information, or control, over any aspect of what is taking place, including decisions that are made about the child's care and treatment [36]. There is a paucity of literature relating to the role of grandparents in, and influence on, the family system [86]. It is generally recognized that they can go through a number of emotions, in addition to providing practical help and advice, without necessarily receiving support, or acknowledgement of their own needs [36].

In a study of grandparents of disabled children, Katz and Kessel [86] found that their satisfaction with their roles related to their views of the illness or disability, their relationship with their adult children, and their own life experiences. For many grandparents, when a child is diagnosed with a life-threatening illness, there can be an overwhelming feeling of guilt that they are alive, while their grandchild is now likely to die before them [36]. In the order of family lifecycles this creates disorder and can be hard to accept, and lead to feelings of helplessness and loss of control. Grandparents can feel anxious, exhausted and powerless. They can also, in some instances, be perceived as domineering and over-protective, and may be resented by the parents if they are felt to be in competition for the rule of the primary carer. However, in working with families, there is some evidence that involving the extended family in a care culture can influence the possibilities of them becoming involved in a positive way [87], and that support from grandparents may be more important to family adaptation than professional help [86].

Families may identify other significant people from within their communities who will be important for professionals to work with, and who may fulfil a role as substitute extended family members in terms of offering support and practical help. However, families also report difficult interactions with the wider community, often feeling isolated and excluded from activities that had previously been important to them, but now no longer seem to hold the same value for them. Many report instances of misplaced sympathy, not welcoming intrusions into their private worlds, [36] and hearing inappropriate things being said. Some report interactions where the subject of their child's illness is ignored completely, some sense that people are avoiding contact with them. Another feature of this changed perception and interaction can be

P.167

found in the example of parents in the school playground, who may hear other parents complaining about what they now perceive as a trivial matter.

In understanding the impact of the child's illness on the wider family, and the potential positive and negative effects on the equilibrium of the family unit of these members and individuals, efforts to support the family in adapting and coping with the situation can be set within the real context of the families' existing systems and processes.

Helping the family

In this final section, the intention is to discuss how families and individual members can be enabled, as far as possible, to cope and live with the reality of childhood life-threatening and life-limiting illness. The term professional is used to encompass all those involved with supporting and caring for families as part of their work.

We propose that to re-focus using a conceptual framework based on partnership and quality of life across a life span requires system changes and innovation at micro and macro levels. The systems framework, described above, is used to locate the emerging themes relating to helping the family. This has been chosen for its simplicity and relevance to practice, allowing readers to identify the arena within which they may be able to influence the family experience, and enabling them to act appropriately and effectively.

Whyte ([23], p. 10) presents a statement of principles that relate to family systems thinking (Box 13.4); these seem fundamental to an understanding of family assessment, and of a model of care that is relevant for this group of families.

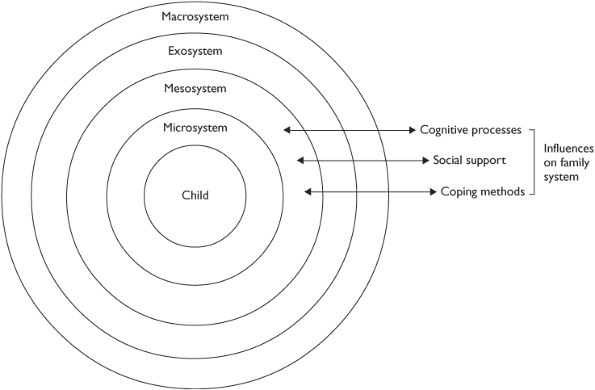

It has been suggested that three processes influence family systems [26; Figure 13.2]:

-

Cognitive processes;

-

Social support;

-

Coping methods.

Box 13.4 Principles of family systems [23, p.10]

-

Parts of the family are related to each other.

-

One part of the family cannot be understood in isolation from the rest of the system.

-

Family functioning is more than just the sum of the parts.

-

A family's structure and organisation are important in determining the behaviour of family members.

-

Communication and feedback mechanisms between family members are important in the functioning of the family system.

|

Fig.13.2 Principles affecting family systems. (Adapted from Thompson and Gustafson [26].) |

P.168

Our view is that social support and coping methods can realistically be the focus for inter-agency and inter-professional services to facilitate and support adaptation. The discussion presented should be viewed as our interpretation and suggestions based on experience of working with families, and on families' own stories, as they have been told to us.

Child and family (micro level)

The micro level relates to the child and family, and an exploration of ways of enabling, supporting and empowering individual family members and family units to cope and adapt to the threatening situation they are in, as well as possible.

Assessment (See also Chapter 12, Assessment)

Lewis [88] suggests that services for children with life-threatening conditions should be family-focused, in order to address the needs, including psychological needs of all family members. Early psychological, social and nursing assessment offers the opportunity to pre-empt problems and to facilitate more effective communication in the family. At a micro level, family disequilibrium occurs at critical times, such as exacerbation of illness [9]. By predicting these critical times, health and social care professionals can optimise the timing and effectiveness of their interventions [9, 89].

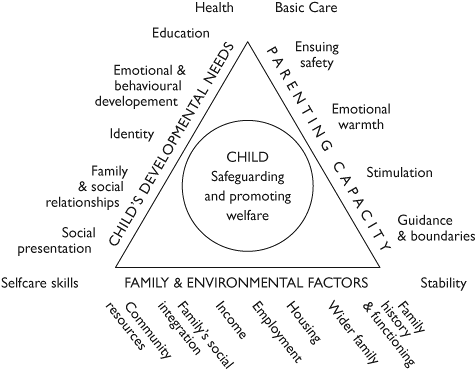

Our experience has been that a systematic assessment [15, 40] process is essential to ensure that family health is fully appreciated, and that both individual and family needs are addressed in partnership. Getting the assessment right for families is the one of the most important factors in delivering an effective service that will meet individual and family needs. It is particularly relevant in the context of inter-professional and inter-agency working, to minimise duplication and ensure all aspects are assessed. The assessment framework triangle (Figure 13.3) has been adopted in the United Kingdom and building on this, a Common Assessment Framework is being developed [6] based on inter-professional and interagency work.

The assessment process can be viewed as the first stage in establishing an interactive working relationship with a family, and an opportunity to explore existing relationships within a family. Time spent at this stage of the professional-family relationship can be viewed as an essential and integral part of the caring process. Trusting relationships that can lead to acceptance by a family of a professional in their lives need to be developed sensitively and gradually [36]. A central aim of the assessment stage of establishing a relationship with a family is to ascertain what the family sees as important for professionals to work on with them and help them with. There will be unique needs, and a robust assessment, undertaken sensitively, will ensure work can be targeted to areas families are able and willing to work on.

An example of this can be related to stress theories; the emphasis here is on family coping not only being related to the nature of the stress, but also to the perception of the meaning of that stress for an individual family [90]. In working with families, professionals need to avoid bracketing families together according to diagnostic groupings when assessing and planning interventions. It is important that value judgements are not made about families who are perceived as either coping or not, when they are in what appear to be similar circumstances.

Following the assessment framework introduced above, we suggest that utilising an assessment process in a systematic way enables families and those working with them to plan individualised care and support that will meet the needs of families and individual members at any given point in time. Our experience, for example, has been that a series of cue questions can have some utility in facilitating an exploratory and interactional experience in which the content and pace are mutually defined' [23, p. 15] (Table 13.3).

Trapp [36] also uses the notion of cue questions that can be used by professionals as they begin, through assessment, to establish an effective working relationship with a family, incorporating mutual understanding.

-

Who are this family?

-

Who do they consist of?

-

What do they value, need, demand and fear?

-

What are their dreams, now and for the future?

[36, p. 77]

|

Fig.13.3 Assessment framework triangle [40]. |

P.169

Table 13.3 The Lifetime Service Model [88]: cue questions for assessment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

This approach offers the potential to guide the professional and family, to ensure that all families have an equal opportunity to review all aspects of their lives and make choices about the priorities for interventions and the nature of professional relationships they engage in at any one point in time. In the Lifetime assessment, for example, alongside the cue questions, standardised assessment measures are incorporated (relating to functional ability as well as psychological measures) to provide internal consistency and for evaluation purposes. An essential part of the assessment process is building in evaluation and reassessment with the family, to reflect the dynamic and changing nature of the family's life span.

Assessment of family structure, functioning and social networks is as necessary as identifying the ill child's symptoms and care needs. This approach directs professionals to take into account the systems within which the family is nested, and moves the focus from family pathology [23] to family health. Common themes arising from assessment relate to a need for information, practical help, emotional support and an understanding of normal family coping and adaptation, and parenting capacity.

Coping and adaptation

It is important to recognise that not all parents of children with a life-threatening or life-limiting condition will experience difficulties with adjustment. Research to date has shown that although mothers have increased risk of adjustment problems, good adjustment is possible. The general outcome for parents, therefore, appears to be much like that for children, particularly when applying Wallander and Varni's model, in that they are at risk of maladjustment, but there is a considerable individual variation in adjustment [91]. There will also be variations during the course of a child's illness trajectory that will affect coping and adjustment, and this means that ongoing support and assessment are needed to inform the appropriate interventions, preventing or reducing distress at specific points in time [91].

There have been few controlled evaluations of interventions to improve the adjustment of children with chronic physical disorders. Both stresses associated with the child's condition and influences within the family system appear to be important for longer-term adjustment [91]. It would seem helpful to identify risk factors in families early [92], along with looking at modifiable factors associated with increasing resistance to the distress being experienced. Relating this to a model of stress and coping [90], it is suggested that the individual's perception of factors [37], and not his or her objective characteristics are the most important determinant of outcome. For example, perceived support may be more important than social network characteristics. If a parent has a negative fatalistic attitude, he or she is less likely to adapt successfully.

Information about the condition and subsequent treatment will need to be given more than once, and over a period of time. It is highly unlikely that it will have been heard or absorbed during the early stages of shock. Quine and Rutter [93] report that a major component of parental satisfaction at diagnosis is the feeling that the paediatrician had communicated the information in a sympathetic manner.

Mothers and recently diagnosed families who experience a family environment of low commitment, limited help and support are going to be at more risk of poor adjustment. Identification of those families who are most at risk is crucial, and interventions must be tailored appropriately. It is important that services address the continual stress that families experience within the context of their environment and provide on-going support, rather than crisis intervention [62]. A proactive model of working is therefore espoused. One example of this is working with individuals and groups of parents to establish coping behaviours and offer specific psychological care. Susan discusses what this has meant for her.

Sometime as a parent you get so immersed in the continuous care and support of the rest of the family that one's own needs and feelings are not recognised. Last year I very hesitantly agreed to attend a counselling course which I found illuminating and extremely helpful. I found, for the first time, that I was able to explore my own anxieties and emotions in a totally secure environment. I know this course proved to be a success with the other parents for we felt the need to meet up again for lunch and a chat'(Susan, mother).

The types of support that are found to be useful by parents vary, but it is often the qualities of the professionals they

P.170