13 - Impact of life-limiting illness on the family

Editors: Goldman, Ann; Hain, Richard; Liben, Stephen

Title: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children, 1st Edition

Copyright 2006 Oxford University Press, 2006 (Chapter 34: Danai Papadatou)

> Table of Contents > Section 2 - Child and family care > 11 - School

11

School

Isabel Wood

Introduction

School plays a unique role in our society, immensely contributing to the social, emotional, aesthetic, and physical development of children. School programmes promote the development of mutual respect, cooperation and social responsibility, and emphasize the worth of each individual. Also the school is the only public institution whose primary role is fostering the cognitive development of young people.

Some might wonder why a child not expected to live beyond the teenage years would bother learning algebra or studying Julius Caesar. Others might question the value of a child with a metabolic disease which limits his ability to communicate or learn how to read and write, being involved in classroom activities. This chapter will look not only at why education can and should play an important role in the lives of children with progressive life-limiting illnesses, but also at the unique challenges faced by educators as they work collaboratively with health care providers to deliver a quality educational experience for these children.

A glossary of terms that are specific to the educational setting is included at the end of this chapter.

Rationale

Why educate children who have progressive life-limiting illnesses?

Every child has a legal right to an education. Numerous influential documents have been released over the past 50 years concerning the education of children with disabilities [1].

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, passed by the United Nations in 1948, declared the inherent dignity and inalienable rights of all members of the human family , and stated that everyone has the right to a free, compulsory education [2].

The Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted in 1989, reaffirmed these rights in Article 23 which states that children with disabilities should not only receive an education but should have effective access to education [3].

In 1990, the World Declaration on Education for All was ratified by UNESCO, and stated in Article 3 that the learning needs of the disabled demand special attention .

The guiding principle of the Salamanca Statement of 1994 [4] stated that schools should accommodate all children regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, emotional, linguistic or other conditions .

The ACT Charter for Children with Life-threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families states that every child shall have access to education [5].

National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services states that, provision of education to sick children is essential and a legal entitlement . [6]

Besides being the right of every child, education or going to school is a normal part of a child's life. Going to school for a child could be equated to going to work for an adult. School can provide not only the routines so important to children but can even provide a purpose for daily living. The child has a reason to get out of bed each morning and an important job to do. Besides providing purpose, being involved in this important job can also provide distractions from the worries of illness.

It is important for children to be viewed by themselves and their peers as normal . Children have a strong desire to be like other children and do what other children do. A child who has suffered physical or intellectual losses may not be able to run like

P.129

other children or read at the same level but he can participate in parallel activities and participate in classroom activities which not only help him to view himself as being normal but help other children to view him as their equal. A child who does not have the energy to stay at school all day may be able to participate in a subject that is important to him, thus enabling him to see that there are still possibilities for learning and growth in his life.

Parents also have a need to see their child participate in the normal routines of life. When parents see their child going to school and participating in the normal activities of childhood, even if in a limited way, the day-to-day coping with their child's illness may seem a bit more purposeful and they may be able to celebrate each milestone, however large or small, in their child's life journey.

Children near the end of life sometimes have an even stronger desire to be a part of school as if trying to compress all their learning into their last days or cling to the small threads still connecting them to the normal world of schooling. They may wish to come to a hospice school to do some math but settle for listening to a story when their energy and attention will not allow them to carry out their desires. They may pursue a frantic quest for information on a particular subject and then die that evening or the next day. Right until the end of life children seek to be connected to the world, and for most children participation in schooling represents normality. By normalizing life, schools prolong living rather than postpone dying [7].

Schools offer opportunities for developing friendships and becoming part of a caring community. Peer relationships have a special role in a child's life, which cannot be filled by adults; they give a child the possibility of sharing thoughts on an equal basis [8]. Peers lock you into life [9]. Close peer relationships enrich a child's life with the normal day-to-day interactions of friends and provide a special support to a child who is sick at home or in the hospital. This also helps the child feel connected to the normal world.

School is a place where children can explore, discover, learn, and create, thus developing their abilities more fully. By participating in activities at which they can be successful, children are able to further develop their abilities and are more likely to develop positive self-esteem. Schools today are mandated to provide opportunities for children to succeed regardless of the academic, physical, or emotional level at which they are working. For the child who is ill, it can be especially rewarding to work on and be successful at achieving goals, whether the goal is completing a specific math problem, completing a science project, or graduating from school with their peers [10].

History

The spectrum of progressive life-limiting illnesses from which a child may suffer encompasses a wide variety of diseases and conditions. Palliative care may extend for weeks, months, or many years [6]. Children who require palliative care, while of school age, range from those working on regular curriculum with little support, to those working on regular curriculum with adaptations, and to those who require major modifications of curriculum. Some of these children will be non-verbal and physically dependent and will require one-on-one full time individual support at school. Nearly all of the children with progressive life-limiting illnesses will qualify as students with special needs . A clearer understanding of the services available for these children within the school system today can be gained by looking at the history of special education and how it has evolved.

Prior to the mid-eighteenth century in Europe, children with disabilities were often neglected, mistreated, and abused. During the nineteenth century, children with disabilities were often rejected by their parents and put in institutions [11]. Such attitudes still prevail in some cultures today as indicated by a parent who recently arrived in Canada from an eastern European country. At a transition meeting for his daughter, the father said, In our country it was assumed that we had done something wrong because we have a child with special needs. Coming to Canada has meant that we can share our sorrow and celebrate our joy.

There are reports of interventions for children with special needs in Spain in the late sixteenth century, but there are no other reports of special needs education in Europe until the mid-eighteenth century. Several pioneer educators in France: de l'Ep e, Periere, Hauy, and Seguin not only established schools for children with special needs but also developed methodologies for working with them. These educators could be said to be the founders of special education as we know it today [10]. Following their lead, several schools for children with hearing impairments were opened in North America in the nineteenth century.

During the early years of the twentieth century in North America, children who were confined to wheelchairs, not toilet trained, or considered uneducable were institutionalized or kept at home where they received no formal schooling. By the 1950s, some parents in North America started to arrange for private education of children with moderate disabilities but, for the most part, children with severe disabilities still received no education [12].

The 1944 Education Act in Britain required local education authorities to identify children who required special education services. Physically handicapped pupils and delicate pupils , defined as children who by reason of impaired physical condition or health or educational development require a change of environment were categorized, but children thought to be uneducable were not included in the regular school system. It was not until the Act of 1970 that provisions in the regular education system were made for these children [13].

P.130

The civil rights movement in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s brought a growing awareness of the rights and human dignity of all individuals. In 1982, David Smith, Chairman of the Special Committee on the Disabled and Handicapped, wrote:

It is precisely in times of economic, political and social strain that the true humanity of a people is proved. In those times, in these present times, a country decides whether it is a nation which includes everyone, or whether it is an economically segregated society, which includes as full members only those who can pay the full price of admission. [14]

The 1970s and 1980s saw legislation being passed that not only ensured the rights of all children to an education but also ensured their right to an education in a regular school setting. In 1975, in the United States, the Education of All Handicapped Children Act was passed. This was followed by various documents such as the Warnock Report in England in 1978, the 1984 report by the Ministry of Education in Victoria, Australia, and the 1991 policy statement of the New Mexico Department of Education all reiterating the right of all children to be educated with their peers [12].

The United Nations issued a number of documents during the 1980s and 1990s which have influenced special education practices around the world [1]. Of particular note is the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education from the World Conference on Special Needs Education held in Spain in June 1994. This statement was approved by delegates from 92 governments and 25 international organizations. The key statements of belief in this document are:

Every child has a fundamental right to education, and must be given the opportunity to achieve and maintain an acceptable level of learning.

Every child has unique characteristics, interests, abilities and learning needs.

Education systems should be designed and educational programmes implemented to take into account the wide diversity of these characteristics and needs.

Those with special education needs must have access to regular schools, which should accommodate them within a child-centred pedagogy capable of meeting those needs.

Regular schools with this inclusive orientation are the most effective measures of combating discriminatory attitudes, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society, and achieving education for all [15].

As has frequently happened throughout history, theories and declarations do not always translate into practice. As recently as in 1999 there have been reports from countries in central and eastern Europe of children with special needs being marginalized or even excluded from local schools due to both attitudes and economic reasons [16]. Recent findings indicate that in Thailand 70% of children with disabilities do not attend schools [17]. Contrasting this is the observation that in North America and western Europe current practice has involved merging special education and regular education into one system with a focus on meeting individual learning needs [18].

Service delivery models

Choosing an educational placement for a child with palliative care needs can be a very difficult process for parents and professionals. Sometimes the best choice is very clear. Other times, because of the complex needs of the child, the decision is emotionally a very difficult one. Both parents and educational professionals need to be aware that there is seldom an absolutely perfect placement and that compromises have often to be made. Parents, in consultation with the personnel involved in the decision making process, need to consider the available options and evaluate the pros and cons for their child at that particular time. If, after a reasonable trial period, the placement does not appear to be satisfactory or if the child's circumstances change, then parents or teaching staff need to re-evaluate the suitability of the placement.

Integrated settings

In recent years, many school systems have moved away from segregated settings for children with special needs towards integrated settings for all children, especially in the elementary grades. The goal of inclusive classrooms is for each child to be valued as a unique and special individual. Children learn that differences are a part of life and that everyone has gifts that they bring to the diversity of the children within a classroom. Children are able to work together, help each other, and make friends with those whom they might not otherwise have recognized as possible friends. Skillful teachers can guide and direct relationships and understandings, helping each child discover their individual strengths.

The success of inclusion in an integrated setting is dependent on the support provided in the classroom and its quality [19]. Support personnel might include a special education resource teacher, a special education assistant, and appropriate consultants such as psychologists, speech language pathologists, doctors, nurses, occupational and physiotherapists, social workers, and counsellors.

Regular classroom with no support

A small number of children with progressive life-limiting illnesses will not be designated as having special needs and will

P.131

have placements in a regular classroom with no additional support. This group might include children following a regular curriculum who have developed a life-shortening condition such as cancer. If no physical or academic adaptations or modifications are required to their educational programme, the teacher, with the help of a counsellor, may be able to meet this child's learning needs.

Regular classroom with support personnel

Most children with progressive life-limiting illnesses will qualify for designation as a student with special needs under a health category. This would result in the child having an Individual Education Plan (IEP) which guarantees collaborative planning by teachers, parents, the child if appropriate, and other appropriate personnel. The educational programme for the child should be discussed thoroughly at an initial IEP meeting. Specific goals for the child, along with support and resources required, would be documented in the IEP. The goals, and progress towards their attainment, would be reviewed and evaluated at subsequent IEP meetings throughout each school year.

Many children with progressive life-limiting illnesses will also have a Care Plan, which would include emergency protocols. If the child has a DNR order all members of the educational team would need to be aware of this and the school would need to know procedures to be followed in an emergency situation. A Care Plan would include personal care details such as seating, lifting, feeding, medication schedules, and physiotherapy requirements. It would also include seizure protocol if applicable, and any pertinent transportation requirements.

When a child with mobility difficulties first registers at a school, a site evaluation by a physiotherapist and occupational therapist would occur. A newer facility should be completely wheelchair accessible but might require some changes. For example, a special desk or work area might be needed and a washroom might require adjustments. An older school might not be wheelchair accessible from streets and sidewalks around the school, and for parking spaces from which a child may be safely dropped off in a wheelchair. Classrooms, playground, drinking fountains, door handles, blackboards, and elevator buttons all need to be wheelchair accessible. In both new and old schools the design of the classroom would be assessed to ensure there is space for the child and the equipment he might require, such as a walker, a standing frame, oxygen, or suctioning equipment. Following this assessment, any necessary adjustments would need to be made.

When applicable the special education assistant or SEA working with the child and a backup staff member would be trained by a physiotherapist and occupational therapist in all aspects of care particular to that child. This might include feeding, transferring, or seizure management. For a child on a ventilator or who has specialized health care needs the assistant working with the child must have appropriate medical training. In some instances two assistants may be required, one for medical needs and one for educational needs. Ideally one person would have both sets of required skills.

A child on a regular programme may need curricular adaptations for written output only and may require SEA assistance for only certain types of assignments. An assistant may work in other classrooms for part of the time or may assist other children in the same classroom, depending on the number of assistants and the number of children with special needs at the school.

There are a wide variety of adaptations which may be used with students depending on the difficulties they are experiencing. Adaptations can include:

using extra thick pencils

using a specialized device to hold papers or books in a visible position

using a computer

scribing by an adult or peer

using photocopied sheets rather than copying from a book

reducing amount of written work a child is expected to complete

breaking assignments into smaller components

providing alternate ways of presenting assignments such as posters, pictures, audio or video recordings, designing games or puzzles

scribing tests or allowing the child to record answers onto a tape

allowing more time for assignments and tests.

Teachers and children will find their own ways of overcoming barriers to successful learning.

With the availability of special adaptations such as track balls, joy sticks, adapted or on-screen keyboards, a computer can often be a key piece of equipment in enabling communication and learning to take place. Word prediction programmes, programmes that use words and symbols, art programmes, and programmes with voice output have all widened the scope of what is possible for children. In some jurisdictions, children will qualify for the loan of adaptive technology through special education technology resource centres. The mandate of such resource centres is to assist children with physical disabilities in reaching their individual potentials with the aid of technological devices.

P.132

For a child on a modified programme, extensive planning is required to develop age-appropriate activities which parallel those of the regular curricula and allow the child to develop skills at his own level. For instance, if a class were studying Ancient Egypt in social studies, a child at an emerging reading and writing level might be able to participate fully in oral discussions, learn from watching videos, and participate in many cooperative group activities. Concepts that are most readily developed through reading might be approached using sources at a simpler level. Instead of requiring that the child submit a written report he might be able, with assistance, to construct a model of a pyramid to submit as his project.

The classroom teacher, special education resource teacher, and special education assistant would work together to plan age-appropriate activities that allow the child on a modified programme to interact positively with his peers but at the same time take into consideration the types of materials from which he learns best. This is a task that becomes increasingly more complex as the child progresses through the intermediate and secondary grades. As children requiring a modified programme become older, the gap between the development of a child and that of his typical classmates may widen, and more class time tends to be spent on highly academic paper and pencil centred activities. This necessitates even more careful planning to enable the child to attain his educational goals in a regular classroom.

A significant number of children with progressive life-limiting illnesses are non-verbal. Some have not developed a system of communication while others have developed communication skills but are losing these because of the progress of their illness. These children will require a thorough assessment by a communication development team specialized in augmented or assistive technology. Such a team often includes an occupational therapist as well as a speech language pathologist. Following an assessment, this team will recommend a communication training programme with either low or high technological equipment depending on the communication level of the child and his motor skills. The team will look at how the child is communicating currently, assess whether the child is able to move to the next stage with practice, and consider which parts of his body the child can move most reliably. Communication devices that can be adapted to operate under the control of almost any muscle group are becoming more widely available. For some children the most reliable body part might be a hand, for others it might be their head, eyes, mouth, feet, or knees. The child may be working at a very basic stage, choosing objects by looking and reaching for them. Others may use eye pointing, looking at objects to make real life choices about the activities they wish to participate in (Figure 11.1). Some children may be developing an understanding of cause and effect and, with sufficient hand control, be able to use a single switch designed to activate a variety of electronic devices such as a tape deck, popcorn maker, blender, or toy. Others may be able to activate devices with prerecorded messages. Some non-verbal children recognize pictures or symbols and are able to use a simple communication board to make choices. Some children may be learning to scan while others might be using a more elaborate communication device or a programme on a computer (Figure 11.2). Once a device is chosen, intensive time and structured individual work with a speech language pathologist is required. After skills are introduced to a student, they can be practiced and used in the classroom in real life situations. Peers can be wonderful motivators, giving the child a purpose for using the new skills they are acquiring.

|

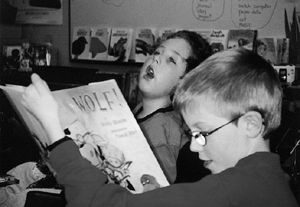

Fig.11.1 A non-verbal student can choose a story by eye pointing and can communicate his enjoyment of the story through body language. (Reproduced with permission of the family.) |

|

Fig.11.2 Non-verbal students are often able to use a single switch to activate electronic devices or a computer program. (Reproduced with permission of the family.) |

P.133

Some children have sufficient hand coordination and dexterity to use standard or a modified form of sign language. A teacher might arrange for someone fluent in sign language to come into the classroom to teach other children basic sign language skills. Sometimes a parent of a child who uses sign language is able and willing to do this.

Some children have sufficient coordination to use laser pointers enabling them to point to an appropriate response on a page, to a printed word that they do not understand, or to communicate a choice they have made. Other children are able, through intensive practice with a trained professional, to learn complicated language systems such as minspeak , which enables them to use more sophisticated modes of communication. A head mouse, which looks like a small dot attached to a child's forehead, can be used to point to letters and symbols on the screen of a computer which then produces a written message with voice output. This device can give a child independence and power. Not only can ideas and thoughts be shared but the child is able to plan, store, and present oral presentations. Questions can be asked in class discussions and the child can even interject with amusing comments. The child can move from a world of isolation to a world of new possibilities.

Some children have had normal functioning before the onset of a degenerative illness which either has taken or is taking communication and motor functioning away. These children often experience tremendous frustration and isolation. They previously have been able to communicate with their friends and have been able to participate in academic endeavours as well as activities such as swimming, gymnastics, and playing the piano. Now they are confined to wheelchairs, either losing or already having lost speech and motor function, and often needing to relearn skills to adapt to their current capabilities. Most of these children want desperately to participate with their peers whether by going to a textiles or foods class, choosing the colors of a T shirt, or deciding what to cook. Most are able to enjoy art and music activities with their peers and the social times at breaks and lunch hour.

Regular class and resource room

Many educational jurisdictions have resource teachers or special education resource teachers who give support to children with special needs either in the classroom or as a pull-out programme in a resource room. The classroom teacher is still responsible for the child's overall educational programme but the resource teacher has an opportunity to meet individual needs in a small group setting. The child might receive instruction in reading and writing, or math skills. He might receive assistance with projects or work that he has missed as a result of absences due to his illness. The resource room offers a setting which can be less distracting and less competitive. It is often a place children can use if the classroom becomes too overwhelming [10]. Here, the resource teacher can listen to individual children and can help them problem solve and develop skills to cope with everyday school life. Resource teachers are sometimes able to offer support to children before and after school and resource rooms are often places where children feel comfortable hanging out during breaks. At the secondary level, structured peer tutoring programmes are often provided to give children an opportunity to receive further assistance as well as the opportunity to interact with their peers in a supportive, structured environment.

Alternative settings

Special Classes

Until the 1960s, the most common way of serving children with special needs was through placement in a special class [10]. Some parents of children who are not able to follow a regular curriculum as a result of a progressive life-limiting illness prefer that their child be accommodated in a special class. These classes usually have teachers with special education training. Typically they have a smaller than usual class size and additional support such as special education assistants. The educational programme offered can be geared to meet specific needs such as life or communication skills. When choosing a placement for children, the educational and parent teams involved often find these classes to be more appropriate for secondary-aged children than a regular placement. In these classes it is possible for children to spend more time working on their individual goals than might be the case in an integrated setting. Additional services such as speech language therapy, communication support, physiotherapy, and nursing support may be more readily available than in a regular setting. Some parents believe that their child benefits from being with and making friends with children at a similar developmental level.

Some children who have been in an integrated setting for elementary school will have a special class placement for secondary school. At the secondary level it becomes increasingly difficult to modify material. A child in secondary school might have up to eight different teachers, each of whom might be responsible for part of the educational programme for more than two hundred students. The strong teacher-student relationship which is so important to successful inclusion can be lacking at the secondary level. Also, a child's previous peer group may have scattered. Some special classes provide for reverse integration by having students from regular classes come into the special class as peer tutors or for social interaction.

P.134

Part-time special class

Some children will be in a special class for core subjects and will join a regular class for other subjects such as music, art, physical education, foods, or textiles. Sometimes a child is also able to join a regular class for subjects such as computer technology or an alternate English or math class. Children in special classes at the secondary level usually appreciate the opportunity to be in regular classes with peers whom they may know from their elementary school.

Special day school

Some parents choose to have their child attend a special school, which can offer small classes, specialized services, and opportunities to progress with less pressure or stress than might be encountered in a regular school. These schools often cater to a particular population and offer nursing care and therapy. Some of these schools are privately operated and can be very expensive. One disadvantage of this type of school is that the children do not have the opportunity to socialize with children in a regular school environment.

Special residential school

Residential schools were once common. They were frequently provided for children who were hearing or visually impaired or who were cognitively lower functioning. Residential schools still exist for specific populations such as hearing or visually impaired [10]. In Vancouver, Canada there are currently two short-term-stay residential schools designed for assessment and rehabilitation following brain injury, neurological damage, stroke, or trauma from, for example, traffic accidents. Because children who stay at residential school are separated from their families, some residential schools encourage the child to live at home and commute to the school each day if possible [10].

Home instruction

Many local education authorities provide home instruction teachers who collaborate with the child's regular school teacher and provide instruction for the child, usually once or twice a week, at their home. This service is frequently accessed by children who are absent from school for significant periods of time due to the progress of their illness. Such children may be undergoing cancer treatment or may not be able to attend school during an outbreak of a communicable disease such as the flu or chickenpox. The home instruction teacher will collaborate with a child's regular school teacher and with parents to develop a programme suitable for the child. Where possible, instruction will follow the curriculum that is being covered in class. Children who have not been able to attend school and are not expected to return due to the progress of their illness might work on appropriate projects or novel studies which interest and motivate them. The teacher will select and structure activities at which the student can be successful, taking into consideration fatigue and other health issues.

Hospital instruction

Many hospitals have school programmes available for children while they are in hospital. These programmes vary widely but are generally for in-patients, although some hospitals also offer programs for well siblings. On occasion, children might commute to a hospital from home to attend the school programme [20]. The aim of these programmes is to promote continuity of educational programming for children, to give children a sense of normality, to offer developmentally appropriate educational activities with which each child can be successful, and to facilitate successful reentry to school after hospitalization. Hospital programme teachers communicate with medical staff, regular school teachers, and parents to coordinate a programme which meets the child's current needs. Many children with palliative care needs are not well enough to go to a classroom while in hospital but the teacher is often able to come to the child's bedside where they may complete assignments or be read to. Communication is frequently encouraged between the child's classmates and the child in hospital.

Hospice school programmes

A child's right to an education has been acknowledged in the ACT [5] charter and in the Joint Briefing of the National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services [6]. Some pediatric hospices have recognized the importance of continuity of education for a child while at a hospice and have established their own school programmes. Hospices frequently offer respite services to children on a palliative care programme. Children on hospice respite programmes may come to the hospice several times during a school year, often for a week at a time. Having a school programme means that children can continue with their schoolwork while they are at the hospice so that they will not be behind when they return to school. School programs also ensure that children can continue with the normal routines of going to school and can engage in activities at which they can be successful. Any school-aged siblings staying at the hospice with their families may be included in the school programme. Frequent consultation with the home school and review of the child's IEP are important to ensure that the child's programme while at the hospice is consistent with their programme at their home school. End-of-life children may also be included in the school programme either in the classroom or at their bedside. Teachers are part of the hospice interdisciplinary team which enables them to be a part of a holistic approach to the care provided by a hospice.

P.135

Communication with parents is an important part of the programme and can occur informally for parents staying at the hospice or through phone calls or family meetings.

Schooling in a children's hospice the Canuck Place experience

Canuck Place Children's Hospice in Vancouver, Canada, was opened in November, 1995. The education programme is staffed by one teacher and one SEA. A team of dedicated volunteers provides additional support in the classroom. These volunteers are an integral and crucial part of the programme.

Because the composition of the classroom at Canuck Place is constantly changing, it is impossible to duplicate the social dynamics of a regular classroom. Frequently, children who have similar illnesses and are of similar ages are booked into the hospice at the same time and, as their families get to know each other through social events and support groups, friendships are formed. It is not unusual to see a sibling reading to a younger child or to a child who is unable to read. Older children look out for younger children and quietly offer help to someone who needs assistance.

The makeup and needs of the classroom are constantly changing requiring staff flexibility. On any given day there may be children from kindergarten to grade 12. Some will be non-verbal, listening to stories and music, participating in a variety of multisensory activities including hand over hand art activities, and working on basic communication skills using eye pointing, communication boards, or switches. Some will be working on a modified programme and may receive assistance in reading a book or completing a math assignment. Some will be working on regular curriculum with adaptations.

In addition to close contact between the hospice teacher and the child's regular teacher and other involved specialists, contact with the student's classmates, either by email or by visits is encouraged. Parents are encouraged to offer input into the school programme for their child. For parents staying at Canuck Place the proximity of family suites to the school room, art room, and Snoezelen or multisensory room, encourages informal communication. One outgrowth of this is that the hospice teacher, at the parent's request, frequently becomes an advocate for the child at his regular school.

Inconsistent provision of education

During May and June of 2003 questionnaires were sent out to pediatric hospices in the United States, England, Wales, Australia, and New Zealand to determine education services provided to children, especially in hospice settings. Responses indicated either a lack of or a very inconsistent education services for children in hospice settings.

There are presently no children's hospices in New Zealand. In Australia, Bear Cottage in South Wales has an informal school programme that operates for two hours a day, staffed by a play therapist, with no separate funding.

Canuck Place in British Columbia, Canada, until recently the only free standing children's hospice in North America, has had a school programme since opening in 1995. The school programme has one full-time certified teacher and one special education assistant. Their salaries are funded by the provincial government. In the United States, George Mark Children's Hospice in California, the first freestanding pediatric hospice in the United States, opened this year, and is planning a have a school programme.

In the United Kingdom, there are almost thirty pediatric hospices but few have formal education programmes. Some hospices have trained teachers on staff but they are not hired to run a school programme. Because of the proximity of schools to hospices some children are able to attend their home school while they are at the hospice. Sometimes hospice staff is able to support the children with their homework and liaise with schools regarding homework or the implications of terminal illness. Helen House in Oxfordshire has recently hired a part time teacher and Quidenham in Norfolk has a teacher who runs a school programme 3 days a week.

While hospices have recognized in their national charters the importance of education for children with life-limiting illnesses [5, 6] most hospices have not yet provided consistent educational programmes.

School reentry

Returning to school after the diagnosis of a progressive life-limiting illness or after a prolonged absence can be a very difficult for a child. [22] The child may have suffered major losses and lifestyle changes. His appearance may have changed due to medical procedures or he may require new equipment such as a ventilator or a gastrostomy tube. [23] These changes may affect a child's emotional health, social interactions, and school performance. Initially it might be necessary for the child to remain at home and receive home instruction. It might seem easier to continue instruction at home but the child would miss much of the social and emotional development that comes from interacting with peers in a school setting. School is the work of childhood. [24] School is crucial to the development of the child's full potential and offers opportunities to grow, learn, and to be successful and creative. In school a child is seen as a student rather than as a patient [22]. School offers the child a sense of hope and the promise of a future. It is important that medical personnel communicate the importance of school to both the family and the child [23, 24].

Both a child and his parents may have concerns about a return to school. It is important that a child life specialist or

P.136

social worker talk with them about these concerns. The child should be prepared for the reactions and comments of other children and should, if possible, be introduced to another child who has faced similar challenges [22, 24].

Communication and cooperation between the home, medical team, and school is vital. While a child is hospitalized, a liaison person should be assigned to communicate medical and home information to the school. A school liaison person, with the parent's permission, should be appointed to receive information and ensure appropriate information is related to all of the child's teachers and any siblings' teachers [22, 24]. The teacher will need information about the child's illness and the effects this illness might have on school performance as well as concerns the child may have. The teacher should be aware of limitations the child may have and special accommodations needed. Social and emotional issues should also be discussed with the teacher. With this information the teacher can plan and develop appropriate educational strategies for the child and any necessary medical or educational resources or support can be put in place [22, 24]. Some children may attend school for only part of the day or for only two or three days a week. At the secondary level children might attend certain subjects only. Each child's reentry will be unique and will require creativity on the part of teachers and other students.

It can be helpful for a class to retain regular contact with a hospitalized child. This can be done through letters, cards, emails or visits. This contact enables the child to feel that he is still a member of the class and that the class is expecting him back [22]. Before a child returns to school it may be appropriate for a child life specialist or a liaison nurse to make a presentation to the class. Some ill children choose to be present for this presentation and some would rather not. Written information on the illness might also be provided [22, 24]. Classmates can be told what they can do to assist the child and to help make the adjustment easier.

It is important that there be ongoing follow-up and communication between the home, the medical team, and the school. For a student with an IEP this communication can occur naturally at designated times throughout the school year. Communication and follow-up should continue throughout the school years, including any transition from secondary school to post-secondary education.

Teachers in school settings

A teacher is an important person in any child's life and can be especially important in the life of a child with a progressive life-limiting illness. It is perhaps the teacher who has the greatest opportunity and responsibility to enhance the quality of life for that child [7]. The teacher, with support from special education resource teachers, has the responsibility of ensuring that appropriate learning resources are available and that any necessary adaptations or modifications are made to curriculum and to the physical environment. Perhaps even more crucial is the responsibility of the teacher to create a caring, supportive atmosphere in the classroom where each child is viewed as special and unique. In this setting a child with a progressive life-limiting illness would know that he is an important member of the class. The teacher might need to work with the class, giving children guidance on how to best make the child feel included. Support would be subtle and unobtrusive, not making the child feel as if he were being singled out. The teacher would also be able to assist with social interactions. He or she could ensure that the child is viewed as an important member of the class even when absent, by mentioning him, and by encouraging classmates to maintain contact with the child. Special events for which the child is absent might be videotaped and replayed for the child.

The teacher might also ensure that a child who is absent from school has access to assignments. For extended absences, a home instruction teacher could be arranged for. Assignments could be emailed to the child and the appropriate teacher contacted. When given updated information regarding the child's changing condition, the teacher would be able to make appropriate decisions about work expectations.

Case Michael is a keen, academically able grade five student who enjoys challenging math problems, reading books like Lord of the Rings, playing strategy games such as Mancala, and playing a wide variety of computer and video games.

Michael has spinal muscular atrophy. He uses a power wheel-chair and follows the regular grade five curriculum. As he tires easily, assignments are often adapted in amount. For instance he might not do all the math questions assigned to other students, he might complete an assignment in class that others are assigned for homework, and he might be given additional time to complete a project in science or social studies. Michael frequently misses school either because of his illness or because of illness in the class to which he should not be exposed, and when he visits a local hospice for respite care. When Michael is unable to attend school his teacher emails assignments to him which, when completed, his mother emails back to the school. When he is at the hospice, all assignments are faxed to the hospice teacher with notes or telephone calls to update Michael on class activities. Michael's teacher emails Michael and encourages him to email her and the class. One task that the teacher asked Michael to complete while he was away was to design a new class seating plan. The design was faxed to his teacher. When Michael returned to school he felt some ownership of the new seating arrangement.

When Michael is absent his teacher mentions him frequently: I wonder what Michael would think about this? or Which group shall we put Michael in? This keeps Michael in the students

P.137

thoughts, as is evident by one boy's comment when the classroom floor was resurfaced. Too bad Michael isn't here. Think of the wheelies he could do around the room! When Michael missed the Valentine's Day Party, his special education assistant, who helps him with physical tasks such as scribing for him and getting out his laptop, arranged to visit the hospice with two of his classmates, bringing all the valentine cards for Michael. His teacher has also visited the hospice several times, bringing different classmates each time. The students were able to play a game with Michael, see the hospice school room, and play with him on the new adapted outdoor merry-go-round. His teacher has reported that this contact has helped the other students, as they now know where Michael goes when he visits the hospice and can talk about what he might be doing. For next year the school staff has arranged for Michael to have the same teacher and most of the same students will be in his class.

Special education assistants

Assistants who work in a school, hospital, or hospice setting with children with progressive life-limiting illnesses are referred to in this chapter as special education assistants or SEAs. These people play an important role and are an integral part of the team that provides support for children with progressive life-limiting illnesses. Without their services it would be almost impossible for many children with palliative care needs to attend regular school.

The role of an SEA is to unobtrusively provide personal care such as feeding and toileting for children with palliative care needs. Children who are on a ventilator require frequent suctioning, and those who have other medical needs must be attended to by medically qualified staff. In these instances the SEA may have medical training as well as training to work in an educational setting. Sometimes there will be a nurse as well as an SEA to provide support for the child.

SEAs work under the direction of the classroom and resource teachers to adapt and modify curriculum and provide individual support to the child as needed. An SEA is trained to know when individual support is needed, and when it is better to remain in the background to foster independence, intervening before the child becomes too frustrated, thus preventing inappropriate behaviour. An SEA should move discreetly to the background in social situations, giving the child ample opportunity to socialize with his or her peers without adult intervention.

Often the child will feel comfortable confiding in the SEA who will then have an opportunity to help the child work through problems. The SEA also has the opportunity to make observations about social interactions of which the teacher may not be aware. Working together, the teacher and the SEA can often enhance social interactions. Sometimes a buddy system is put in place for recess and lunch, but often an SEA is able to foster inclusion in an even more natural way. An SEA has the opportunity to provide the child with the support he needs to be successful physically, academically, emotionally, and socially, enabling him to develop the confidence needed to take more risks in the school setting. As part of this an SEA should be aware of the importance of having the child feel that he or she is a part of, not separate from, the class. To foster normality the SEA will often direct parents to talk with the teacher about academic or social updates. The child will be encouraged to direct pertinent questions to the teacher and hand work in to the teacher rather than to the SEA.

Parents

Discovering that their child has a disability can be devastating for parents. Discovering that their child has a progressive life-limiting illness brings a new dimension to that devastation as it threatens one of the strongest of human bonds [25]. The degree to which parents are able to come to terms with and accept these conditions varies from parent to parent. For many parents, life following such a diagnosis is a series of crises. Parents find it difficult when their child first enters the school system and often are in the position of having to lobby for needed support for their child. At some point there may be a teacher or a special education assistant who they feel is not a good match for their child, which causes additional stress. As one parent said, I just feel that everything is under control and then I need to solve another problem.

When children move from elementary school to secondary school there can be a great deal of parental anxiety especially when a change in the type of placement is being considered. It is crucial for parents to have the opportunity to be involved in the choice of placement and to know that their views are being taken into consideration. At times the pressure of the school day may seem overwhelming but most parents do want their child to have this normal experience.

Parents with children who have progressive life-limiting illnesses can be under tremendous physical and emotional strain. Their child often has complicated physical care needs including lifting and physiotherapy. Specialized equipment may be required and there are often numerous appointments related to the child's illness. It may not be possible for both parents to maintain full time employment, thus creating financial strains for the family. Parents often feel guilty that they are not able to spend enough time with their spouse or their other children. Although the time and energy of these parents is stretched, regular communication with them is still very important. Parents need to be involved in placement decisions, in school reentry plans, and in regular IEP meetings.

P.138

Parents can be kept informed about their child's programme and performance by telephone, meetings, or a communication book. Parents know their child better than anyone. They hold key information and knowledge [20] and should be full collaborative partners with the educational team.

There may be times in their child's school life when parents feel that, even after having gone through the process of IEP meetings and collaboration, the needs of their child are not being met. Many parents of special needs students have advocated publicly for what they believed their child needed. In some educational jurisdictions it is now possible to arrange for another person (a Parent Facilitator or an Independent Parental Supporter) to guide and support the parents to ensure that their voice is being heard. There may also be parent partnership groups that provide information, advice and guidance on issues and who are able to help guide a parent through an unfamiliar system [20, 26].

|

Fig.11.3 Siblings often enjoy reading stories to children who are not able to read. (Reproduced with permission of the families.) |

Siblings

Siblings have a special relationship that no other can duplicate. Although they may not always get along, may be jealous of each other, and even sometimes say they hate each other, there is always a great potential for support, companionship, and love. Siblings share a common history and common bonds [27].

The care of a child with a progressive life-limiting illness often totally consumes parents leaving little time for other children in the family. These children may feel overwhelmed and neglected and have been referred to as living in houses of chronic sorrow [28].

During the progress of a terminal illness, a sibling may display a wide variety of behaviours at school. Some siblings may display no outward signs of emotional upset or disturbance. They may have a close relationship with their brother or sister and may find opportunities at recess or lunch to play with their brother or sister or give assistance with books or papers. Some siblings display amazing empathy and patience with classmates or other children in the school who have special needs (Figure 11.3).

Many siblings display behaviours that suggest they may be having difficulties adjusting to the illness of their brother or sister. Frequently they have attention-seeking behaviours and short attention spans. Many have difficulty sustaining effort on schoolwork and in learning new concepts. Others may have an overly strong desire to do everything perfectly and may become upset when they make mistakes. Some may seem to be overly anxious about the well being of other brothers and sisters in the family to the extent of taking on the role of a parent.

During this period, school can be a safe haven for some siblings. School may be the one place where siblings can be acknowledged for themselves rather than as the brother or sister of their ill sibling. At school, unlike at home, life tends to remain the same, including predictable routines [8]. School also provides opportunities to socialize with friends, whom they may no longer be able to see after school. Siblings can confide in their friends, socialize and enjoy the normal activities of childhood. During school hours it may be possible to forget what is going on at home.

It is important for teachers of siblings to have information about how the sibling is reacting to the progress of the illness outside the school setting. The teacher will be aware of any changes in school performance. The teacher should also look for any persistent signs of depression, social withdrawal, anxiety, aggression, or low self-esteem [27] which would indicate the possible necessity of intervention. The teacher may schedule times for the sibling to meet with a school counsellor.

The impact of the death of a brother or sister can last a lifetime but siblings who are comforted, taught, included, and validated [27] can grow and develop into emotionally healthy adults. Teachers can play an important role in supporting siblings. Teachers can listen to them and provide opportunities for them to express their feelings through writing, art, physical education, music, and drama. They can ensure that siblings are included and important members of their class. Teachers have an important role in creating a supportive learning environment where caring classmates can also be part of the healing process. As well as arranging for counselling through the school, the teacher can assist in ensuring that the family is aware of outside resources that are available for siblings, including bereavement groups, play therapy, and private counselling.

P.139

Dealing with death

In some cultures death is an accepted part of life, but in many cultures it is a subject adults find very difficult to talk about [29]. The knowledge that death is irreversible, inevitable, and universal is usually assimilated by children around 7 or 8 years of age. Because children have a limited capacity to tolerate emotional pain and a limited ability to verbalize their feelings, they may avoid talking about their grief [29]. Children are interested in death as evidenced in their games and stories, and some educators feel that death education should be an integral part of the curriculum [30]. It is helpful for students to have had the opportunity to think about and discuss death before a death occurs in their lives, thus giving them opportunities to receive support and have questions answered [30].

The death of a classmate can be a very traumatic experience for the entire class resulting in changes which children may find difficult to deal with [31]. Many schools have protocols for informing children about the death of another child. Critical incident or response teams, which include an administrator, teachers, counsellors, and district specialists, give support to teachers and children [31, 32]. The type of response made by this team at the time of death will depend on the ages and levels of emotional maturity of the children and the cause of death [31].

An anticipated death allows time to plan and prepare, making it important that the school personnel understand both the child's condition and prognosis [31]. Some research has shown that children fare best when honest discussions about a terminal illness occur from the time of diagnosis and when open communication appropriate to the child's developmental stage and emotional needs is maintained [33]. Teachers frequently use literature and discussion to help prepare children for the death of a classmate and to help deal with questions and emotions before and after the death. Some teachers will have attended professional development sessions on supporting children around death. In senior grades death can be touched on in literature, history, and biology [30]. Models of grief suggest that bereaved children need to understand, grieve, commemorate, and move on [34]. This means that is important for children to understand that death is universal and irreversible, they must be able to experience and express their feelings, they should be involved in some sort of remembrance or commemoration service, and then they must move on to other relationships. [34] It is usually the critical incident or response team that will initiate this response with follow up by counsellors and teachers.

The death of a child can have a great impact on teachers and other staff members who have worked closely with that child. Each teacher will react differently depending upon their own personal attitudes and beliefs about death, their personal experiences with death, and what is happening in their own life at that particular time. Some teachers may be able to cope effectively with little or no support while others may need to access school support groups or counselling provided by their educational jurisdiction. It is important that support be provided for staff by trained professionals not only for the teachers' own emotional and physical well being but also so that these teachers can effectively give support to the children with whom they are working. A school counsellor may be asked to come into the classroom to talk with the children or to provide resources and suggest strategies.

Some teachers may need support in dealing not only with their own attitudes and feelings about death and dying but also those of their students. Within present day Greek culture the death of a child is perceived as unnatural, unfair, and tragic. In 1997, a group of Greek educators were involved in a multidisciplinary year long training programme on supporting seriously ill and bereaved children. These educators have offered seminars and workshops in schools but many teachers have reported that they still feel unprepared to deal with the death of one of their students [35].

In France, death education was removed from the curriculum because of religious pressures [30]. In the United Kingdom, direct classroom instruction around death is part of the normal curriculum [36]. In 1999, a reflection time on matters of death and grieving was added to the curriculum. Training for some teachers was introduced and in September 2002, death and grieving education became a component of the school curriculum under the Personal, Social, and Health Education programme [30]. Hospice programmes in the United Kingdom sometimes act as resources to schools before and after the death of a child, as an extension to patient care [36].

The child with a progressive life-limiting illness

It is difficult to make generalizations about children with a progressive life-limiting illness. No two children with the same diagnosis will present identically. Working with these children only reinforces the belief that all children are unique and, as such, have very unique needs. There are, however, observations that can be made about these children. Many children with physical limitations are creative and resourceful. They are creative in the ways they have discovered they can do things. For instance, some children know which pens work best for art projects, which books will best support the mouse on the computer, and which type of calculator is easiest to use. They may not be able to run with a kite but they can fly a kite when the

P.140

line is attached to their power chair and they will tell you where and how they want the line attached. They may not be able to cut with scissors but they can plan an entire model town complete with a tower to launch a rocket and will tell you exactly what they need you to do to help the project come to fruition.

There is a Tibetan saying that begins: Children are our real teachers. Listen carefully. Perhaps because children with progressive life-limiting illnesses lose control in so many areas of their lives, it is even more important that they be given choices. Non verbal children may be able to tell you with their eyes which book they want and their body language can tell you that you have not interpreted their choice correctly. Other children may be very decisive about what they feel is important and what goals they want to work towards. Often activities of choice that adults might feel are important are not those that the child feels are important at all. When choices can be accommodated the child gains some control over his environment.

These children understand what it means to need help and how it feels to be vulnerable. Perhaps this is why so many are supportive of each other. It is not uncommon in a hospice setting to see one child asking for help on behalf of another child. Older children will consider younger children when planning outings and will offer to help younger or non-verbal children or read them a story.

As with all children, children living with progressive life-limiting illnesses are proud of their accomplishments. They feel good about their accomplishments, whether it be the good mark they received on a math test or the goal they scored in a power hockey or soccer game. They are able to take pride in attaining goals, whether the goal is to complete a math assignment, read a novel, or graduate from secondary school.

One of the most amazing attributes of many of these children is the ability to accept their illness in their stride. Yes, there are times when a teacher hears, It's just not fair! but many of these children are strong, brave and courageous. Without flinching they can ask an adult to position their arms or legs, push their hair back, or blow their nose and then proceed with whatever it was that they were doing. These children are like any children. They want to learn, grow, play, laugh, and have fun. They have the same hopes and dreams as other children, the only difference being that they may not have as long to realize these hopes and dreams. Like a butterfly they need to stretch their wings and fly because they have much quality living to do in a limited period of time.

Case Greg is a 17-year-old boy who spends a significant amount of time at his computer, staying in contact with friends by email. He enjoys recreational activities, including indoor rock climbing with the recreational therapist at Canuck Place. He would love to try sky diving some day.

Greg has been on an adapted programme at school. He often needs help scribing his work as he has Friedrich's ataxia which has made his hands weak and requires that he use a wheelchair. Greg tires easily and requires additional time to complete assignments. Over the past years, his teachers have often commented that he is a capable student but has difficulty keeping up with the workload of the regular secondary school curriculum. His teachers and counsellor recommended that Greg take 4 years to complete grades 11 and 12, his final years of school, before attending college.

Greg, however, set himself the goal of completing grades 11 and 12 in 2 years and graduating with his peers with whom he had attended school since kindergarten. Whenever he made respite visits to Canuck Place he was always keen to complete his assignments and keep up to date in his senior English course. Recently his case manager informed us that Greg had been on the Honour Roll at his school this past term, received a citizenship award, and a most inspiring person award. Greg requested that he be permitted to say a few words at the Awards Assembly. In his speech Greg told the audience that people thought he should take 4 years instead of 2 to graduate but that the most important thing for him was to graduate with his friends. He went on to say that after making this decision he decided what he had to do to make his dream come true. He concluded by saying, If I can do it, so can you!

Conclusion

School is an important part of life for all children. For the child with a progressive life-limiting illness, the school is a place where children are able to develop their skills and abilities to their fullest potential and develop and maintain connections with peers. Schools also provide children with normal connections to the wider world, thus giving them a sense of hope. Many of these children require IEPs that necessitate additional planning, resources and support. There are challenges in meeting the individual needs of each child and ensuring they progress academically, socially, and emotionally. There is no road map, guidebook, or set of rules for this journey. Flexibility, creativity, good judgment, sensitivity, and love are required as each child's needs are assessed, the best possible placement is made, and all available resources and supports are put in place. With resources and services constantly in a state of flux, teachers, parents, and society must constantly be prepared to advocate for the best possible education for these children.

Having a child with a progressive life-limiting illness as a member of a class can be a very enriching experience for the teacher and the entire class. Together the children can learn and grow. Peers are able to offer friendship, understanding, and support. In return they will often develop

P.141

empathy and a deeper appreciation for human worth and dignity. Children with progressive life-limiting illnesses often gain insights and wisdom beyond their years. Given opportunities and a willingness to share these thoughts and feelings, classmates may gain significant understandings and be challenged to think about issues beyond the prescribed curriculum.

Together, all members of the class, whether in a regular, special, hospital or hospice setting can learn the importance of taking time to listen and to learn. They can learn to truly listen to each other. They can learn how important it is to care for each other, to be a true friend, and to grow together. They can learn the importance of living in the moment and being present for each other. These children will be able to fully appreciate the words translated from Sanskrit:

Look to this day for it is life, the very life of life,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

For yesterday is but a dream and tomorrow is only a vision,

But today well spent makes every yesterday a dream of happiness

and every tomorrow a vision of hope.

Look well therefore to this day! [37]

Glossary

Adapted programme

student is following the regular curriculum for his or her grade level and will meet the learning outcomes with adaptations such as using a computer, having a scribe, having more time for assignments and tests

Augmentative technology

devices designed to support, augment, or assist communication using whatever skills an individual possesses

Case manager

the individual in the school designated to manage the case of a student with special needs; this individual will arrange IEP meetings, coordinate services in the school and coordinate services from outside professionals such as doctors, nurses, occupational and physiotherapists, speech language therapists, social workers, etc.; see Special Education Resource Teacher/Special Needs Coordinator

Child Dependent

individuals of school age (5 18 years old) Dependent a child who is completely dependent on others for meeting all major daily living needs; assistance will be necessary for the child to attend school

Designation

the process by which a child is assessed for special needs and then assigned a government category for the purpose of funding and service

Elementary School

kindergarten to grade seven (usually 5 12)

Inclusion

unified systems of education with provision of appropriate education for all; all children are included, participating, valued members of the class

Individual Education Plan (IEP)

written plan developed by an educational Plan team which includes parents and other appropriate professionals who are working with the child; plan consists of long and short term goals for the child and includes modifications or adaptations for the child and support which will be provided

Integration

sometimes referred to as mainstreaming; the provision of an appropriate education for children with special needs in a regular education setting

Modified Programme

child is following a parallel programme with learning activities which will enable the child to develop academic, social, and emotional skills; child will not meet the learning outcomes for his grade level

Regular

when referring to a regular school, class, setting, or placement this implies a setting where all children regardless of abilities, special needs, or health status are educated in the same environment. In this settingchildren with special needs learn side by side with their normally developing peers

Regular Programme

child's educational programme falls within the widely held expectations forhis grade level

Secondary School Special Education Assistants (SEA)

grades 8 12 (13 17 years old] referred to as aides, teaching assistants, school and student support workers, child care workers; these paraprofessionals work in the classroom under the direction of the teacher supporting children with special needs physically, academically, and socially

Special Education Resource Teacher/Special Needs Coordinator

education; manages cases of children with special needs and often works with them individually, in small groups, or in the classroom

Statement

legal documentation, drawn up after assessment by the education authority, which outlines special education needs of a child and service required (In the United Kingdom)

Transition

the process of moving from one programme or environment to another

P.142

References

1. Desai, I. Inclusion: Disability and educational provision in Australia. Proceedings of Pre-Conference Symposium; Disability and Policy in 21st Century: Refocus on and Old Issue, Melbourne, Australia, 9 September 2001.

2. United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Resolution 217 A (III). Proceedings of the General Assembly of the United Nations. Geneva, Switzerland, 10 December 1948.

3. United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Resolution 44/25. Proceedings of General Assembly of the United Nations. Geneva, Switzerland, 20 November 1989.

4. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. Proceedings of World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Salamanca, Spain, June 7 10, 1994.

5. Association for Children with Life-threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families. ACT Charter for children with Life-Threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families. (3rd edition. [pamphlet]). ACT, Bristol, 1998.

6. Elston, S. and Goldman, A. Joint briefing with ACT and ACH; palliative care for children [briefing bulletin]. National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services, London, 2001.

7. Jeffrey, P. Enhancing their lives: A challenge for education. In J.D. Baum, F. Dominica, R. Woodward, eds. Listen My child has a Lot of Living to do. London: Oxford University Press, 1990, pp. 133 7.

8. Trapp, A. Support for the family. In A. Goldman, eds. Care of the Dying Child. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994, pp. 76 92.

9. Lavelle, J. Education and the sick child. In L. Hill, ed. Caring for Dying Children and Their Families. London: Chapman and Hall 1994, pp. 87 105.

10. Winzer, M. Children with exceptionalities in Canadian classrooms (6th edition). Toronto: Prentice Hall, 2002.

11. Winzer, M. and Mazurek, K. (ed). From tolerance to acceptance to celebration: including students with severe disabilities. In Special Education in the 21st Century: Issues of inclusion and reform. Gallaudets University Press, Washington DC: 2000, pp. 175 97.

12. Winzer, M. and Mazurek, K. ed. The inclusion movement: a goal for restructuring special education. In: Special education in the 21st Century: Issues of inclusion and reform. pp. 27 40. Washington DC, Gallaudet University Press, 2000, 175 197.

13. Spalding, B. Special educational needs in the mainstream school. Liverpool: University of Liverpool, Department of Education, Liverpool, 1999. Available from: http://www.liv.ac.uk/education/inced/sen/index.html. Accessed 2003 June 5.

14. Smith, D. Introduction of progress report. Special committee on the disabled and handicapped. Proceedings of the first session, 30 sec parliament, June 1982, Ottawa, Canada.

15. Lindsay, G. Inclusive education: A critical perspective. Br J Special Educat 2003;30(1):3 12.

16. Ainscow, M., Haile-Giorgis, M. Educational arrangements for children categorized as having special needs. Eur J Special Needs Educ 1999;14(2):103 21.

17. Pierce, N. Editorial on Thailand. Rehab Review 2002;24(5):13 15.

18. Andrews, J. and Lupart, J. Historical foundations of inclusive education. The Inclusive Classroom. Scarborough, Nelson Thompson Learning, pp. 25 48.

19. Farrell, P. Special education in the last twenty years: Have things really got better? Br J Special Edu 28(1): 3 9.

20. Farrell, P. and Harris, K. Access to education for children with medical needs-a map of best practice. [pamphlet]. Sherwood Park: DfES Publications, 2001.

21. Canuck Place Children's Hospice. The Story of Canuck Place. Available at: http://www.canuckplace.com/about/story.html. Accessed: 2003 May 9.

22. Sexson, S.B. and Madan-Swain, A. School reentry for the child with chronic illness. J Learn Disabil 1993;26(2):115 37.

23. Hochu, J. The role of the child life specialist assisting the pediatric palliative patient return to school. Hospice News Spring 2003;7:16.

24. Leigh, L. and Miles, M.A. Education Issues for children with cancer. In P.A. Pizzo, and D.G. Poplack, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology 4th edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia 2002, pp. 1463 76.

25. Overton, J. Development of children's hospices in the UK. Eur J Palliat Care 2001;8(1):30 3.

26. Vancouver School Board. Parent Advocacy Program. Available at: http://www.vsb.bc.ca/parents/parentadv.htm. Accessed: 2003 July 4.

27. Davies, B. The grief of siblings. In M.B. Webb, ed. Helping Bereaved Children. New York: Guilford Press, 2002, pp. 94 127.

28. Bluebond Langner, M. Worlds of dying children and their well siblings. In K. Doka, ed. Children Mourning Mourning Children. Washington: Hospice Association of America.

29. Webb, N.B. The child and death. In Webb N.B., editor. Helping Bereaved Children. New York: Guilford Press; 2002, pp. 3 18.

30. Abras, M. Teaching children to understand death and grieving. Eur J Palliat Care 2002;9(6):256 7.

31. Stevenson, R.G. Sudden death in schools. In N.B. Webb, ed. Helping Bereaved Children. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 194 213.

32. Vancouver School Board. School emergency and crisis response flipbook. Vancouver School Board, Vancouver, (revised 2003).