Interface

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Viewpoints

The interface for a digital game is a combination of the viewpoint of the game environment and the visual display of the game status and controls that allow the user to interact with the system. The controls, viewpoint, and interface all work together symbiotically to create the game experience and allow the player to understand and have agency within the system.

As with control systems, the viewpoints for the first videogames were limited, and mainly limited to text descriptions of the environment. This doesn’t mean that they were ineffective—just the opposite—anyone who remembers playing an Infocom text adventure probably also remembers the sense of immersion that can come from a well- written storyline.

However, once computer displays were able to move beyond the display of text, several major graphic viewpoints for interfaces were developed fairly early on. These viewpoints have evolved in complexity as technology has advanced, but they remain essentially the same today as they were the first time we looked down on the classic Pong tennis court.

Overhead view

Looking directly down at an object is a somewhat unnatural angle, and today, this viewpoint is primarily used for level maps and digital versions of boardgames, but early games used this viewpoint quite a bit, in everything from sports and adventure games, to action puzzles like Pac-Man.

11.6 Overhead views: Atari Adventure and Football, MSN Game Zone Backgammon

MSN Game Zone trademark Microsoft Corporation

Side view

The side view is popular with arcade and puzzle games like Donkey Kong, Tetris, and The Incredible Machine, but probably has had the most influence in the form of the side-scroller. This type of interface is largely out of favor now, but that doesn’t mean that we should ignore the power and simplicity afforded by this viewpoint. The fact that the player only has to control units in two planes leaves a significant amount of brainspace for solving complex puzzles and other forms of play.

First person view

This is the current favorite among many gamers and designers. It creates immediacy and empathy with the main character, literally putting the player in their shoes. This view also limits the player’s overall knowledge—allowing for dramatic moments of tension and surprise as enemies may lurk around any corner, or even approach from the rear.

Isometric view

Popular in strategy games, construction simulations, and role-playing games, this viewpoint is a 3D space with no linear perspective. It is very good at allowing a “god’s eye” view. The distinctive feature of this point of view is the amount of information the player can easily have access to. Recently, games like Myth and WarCraft III have used the isometric view in a fully 3D environment, allowing the player to move her perspective closer or further away from the action.

Third person view

A direct descendant of the side view, this view generally follows a character closely, but doesn’t step directly inside their view. Adventure games, sports games, and other games that depend on a more detailed control of character actions tend to use this viewpoint.

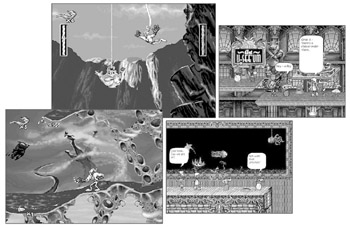

11.7 Side views: Earthworm Jim and Castle Infinity

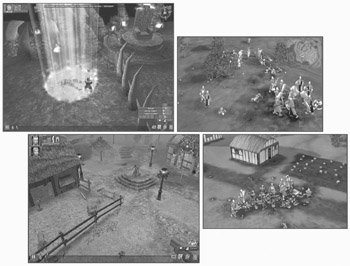

11.8 Isometric views: Myth and Dungeon Siege

Dungeon Siege trademark Microsoft Corporation

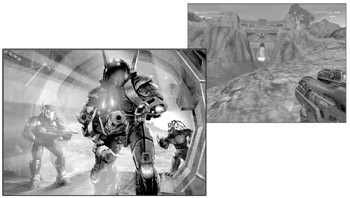

11.9 First-person view: Unreal 2

These views have become so ingrained in how we think of games that often a designer will choose without stopping to consider several important questions that lie behind all interface design: what is the purpose of the interface? What is the state of the game, and how much information should the player know about it?

In Chapter 5 we discussed the “information structure” of games—how much and what type of information about the game state was given to each player. The viewpoints we’ve just discussed provide degrees of access to the state of the world, as well as placing the player in varying relationship to the character or other game objects that they must deal with. This makes the choice of interface view both a formal and a dramatic design element.

Should the player feel extremely close to the game character—sharing its sense of movement, in addition to its lack of knowledge at times? Or, should the player remain close, but somewhat outside of the character, able to see more of the environment, perhaps pick up on clues or tools that might not be in the character’s direct vision? Perhaps there is no character in your game, or maybe there’s no world—in this case, what is the view of the game state that makes the most sense for your design?

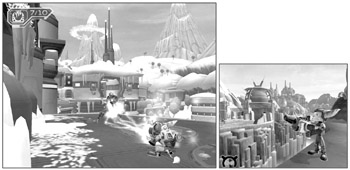

11.10 Third-person view: Ratchet & Clank

Exercise 11.3: Viewpoint

What viewpoint is the best choice for your original game? Why? Describe how this choice affects both the formal and dramatic elements of your game.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 162