Hack 74. Live Life in the Fast Lane (You re Already In)

Hack 74. Live Life in the Fast Lane (You're Already In) By applying the laws of chance, knowledge of human nature, and some facts about highway-driving behavior, you can make wiser lane-changing decisions. Nothing is more frustrating than being stuck in a traffic jam, especially when the other cars are moving faster than you. While it is tempting to change to a faster lane, it turns out that your judgment might be flawed and the other lane is probably not really any faster than yours. Deciding to change lanes when you shouldn't is a dangerous proposition. Not only are the majority of car crashes due to driver error, but 300,000 car accidents each year in the U.S. occur specifically while a driver is changing lanes. Of course, if you are in a hurry and the lane next to you is moving more quickly, as long as you do so safely, why shouldn't a smart driver move into the fast lanes of life? After all, as I've patiently explained to court authorities a number of times, a "good" driver isn't necessarily a safer driver; he's just a driver who gets where he wants to go as quickly as possible. The problem is that recent research involving statistically based computer simulations suggests that drivers will usually judge another lane is moving more quickly than theirs, even if it is actually moving at the same speed! This misperception, survey research shows, is enough for most drivers to try to change into that other lane. Skips, Slips, and EpochsOur perceptual world while on a busy highway or in a traffic jam consists of the big truck in front of us, the cars we see to the right and left of us, and the poor sap stuck behind us. To judge our speed of travel, while we do have a speedometer, the most compelling data tends to be the cars on either side of us. (Are they passing us or are we passing them?) Traffic researchers call the times when you are passing other cars skips and the times when other cars are passing you slips. Recent research refers to skips as passing epochs and slips as being-overtaken epochs. It probably does not surprise you that drivers greatly prefer passing epochs over being-overtaken epochs.

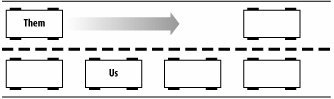

In addition to looking for faster lanes to move into, drivers have another goal, which is to keep their own vehicle moving as quickly as possible, or at least close to their target speed (which might be the speed limit, for example). If there are perceived gaps between themselves and the vehicle in front of them, and they are not currently moving at their target speed, drivers will accelerate to close the gap. It is these bursts of acceleration that account for the skips (periods of passing other cars) and slips (periods of other cars passing them). We are likely to experience more periods of time when we are being passed than periods when we are doing the passing. It is this perceived inequity that can result in drivers concluding that they are in the slow lane, even if both lanes are equally slow. Imagine two lanes of traffic side by side that are moving at the same average speed. Gaps between cars form randomly; more accurately, they form systematically, but based on a random starting configuration. Gaps are filled as they form, and when gaps are filled, cars have accelerated.

Drivers on crowded roads occasionally have gaps they seek to close, but they actually spend much more time (relatively speaking) moving slowly or not moving at all. During those times of slow movement, which, of course, take more time, there will occasionally be cars in other lanes filling gaps and passing the drivers in those temporarily slow lanes. As measured by epochs, for any one driver there will be more time spent being passed than there will be time spent doing the passing. This is because you pass while moving quickly and you are passed when you are moving slowly. Figure 6-9 paints a picture of this perception. Figure 6-9. The perception of time spent getting passed Sitting still while watching other cars accelerate to fill gaps creates the illusion that our lane is moving more slowly. Probability and Traffic PatternsCanadian researchers Donald Redelmeier and Robert Tobshirani, who conducted computer simulations to determine the accuracy of driver perceptions of other lanes' speed, made some assumptions about traffic patterns that were based on the normal distribution [Hack #23]. To mirror the reality that a particular pattern of spacing on a crowded highway has several causes (conditions, exits and entrances, and so on), they randomly assigned intervals between moving cars based on two normal distributions: 90 percent of intervals were about two meters apart, give or take a 10th of a meter, while 10 percent of the intervals were 100 meters apart, give or take 5 meters. At the start of each of hundreds of simulations, cars were created and spaced following this randomization plan. The researchers created data for two lanes of traffic moving in the same direction at the same speed, full of hundreds of imaginary vehicles with typical acceleration and braking capabilities. They programmed in a safe driver strategy of moving up when there was space in a lane, but not getting too close. Their simulated drivers were not allowed to get too close to another vehicle's tailgate. Also, they were not allowed to change lanes, which must have been frustrating for the little computer-controlled drivers. No accidents here.

Making Wise Lane-Changing DecisionsRedelmeier and Tobshirani found that 13 percent of the time, cars are either passing or being passed. Most of the time, cars are running equal to each other. While there was a better chance that any particular driver was being passed than that she was doing the passing, when she did pass cars, she passed a bunch. The math worked out to a draw in terms of cars passed and the number of cars doing the passing. The total number of cars overtaken by our driver was equal to the number of cars that passed her. Under crowded driving conditions, the other lane will seem greener much of the time. There are some ways to deal with the misperception and make wiser (and statistically safer) driving choices:

The wisest tactic when it comes to dealing with the likely misperception that the other lane is faster than yours might be the simplest. Just don't pay attention to it. The simulations show that if you look at other lanes half as often, you'll notice cars passing you half as often. I suppose, though, that we don't need a statistical analysis to tell us this. Instead of the cars beside you, pay more attention to the cars behind you. You're way ahead of them and there are thousands of them. You've already won that game. See Also

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 114