Other C Nuances

| The following sections touch on features and dark corners of the C language where security-relevant mistakes could be made. Not many real-world examples of these vulnerabilities are available, yet you should still be aware of the potential risks. Some examples might seem contrived, but try to imagine them as hidden beneath layers of macros and interdependent functions, and they might seem more realistic. Order of EvaluationFor most operators, C doesn't guarantee the order of evaluation of operands or the order of assignments from expression "side effects." For example, consider this code: printf("%d\n", i++, i++);There's no guarantee in which order the two increments are performed, and you'll find that the output varies based on the compiler and the architecture on which you compile the program. The only operators for which order of evaluation is guaranteed are &&, ||, ?:, and ,. Note that the comma doesn't refer to the arguments of a function; their evaluation order is implementation defined. So in something as simple as the following code, there's no guarantee that a() is called before b(): x = a() + b(); Ambiguous side effects are slightly different from ambiguous order of evaluation, but they have similar consequences. A side effect is an expression that causes the modification of a variablean assignment or increment operator, such as ++. The order of evaluation of side effects isn't defined within the same expression, so something like the following is implementation defined and, therefore, could cause problems: a[i] = i++; How could these problems have a security impact? In Listing 6-30, the developer uses the getstr() call to get the user string and pass string from some external source. However, if the system is recompiled and the order of evaluation for the getstr() function changes, the code could end up logging the password instead of the username. Admittedly, it would be a low-risk issue caught during testing. Listing 6-30. Order of Evaluation Logic Vulnerability

Listing 6-31 has a copy_packet() function that reads a packet from the network. It uses the GET32() macro to pull an integer from the packet and advance the pointer. There's a provision for optional padding in the protocol, and the presence of the padding size field is indicated by a flag in the packet header. So if FLAG_PADDING is set, the order of evaluation of the GET32() macros for calculating the datasize could possibly be reversed. If the padding option is in a fairly unused part of the protocol, an error of this nature could go undetected in production use. Listing 6-31. Order of Evaluation Macro Vulnerability

Structure PaddingOne somewhat obscure feature of C structures is that structure members don't have to be laid out contiguously in memory. The order of members is guaranteed to follow the order programmers specify, but structure padding can be used between members to facilitate alignment and performance needs. Here's an example of a simple structure: struct bob { int a; unsigned short b; unsigned char c; };What do you think sizeof(bob) is? A reasonable guess is 7; that's sizeof(a) + sizeof(b) + sizeof(c), which is 4 + 2 + 1. However, most compilers return 8 because they insert structure padding! This behavior is somewhat obscure now, but it will definitely become a well-known phenomenon as more 64-bit code is introduced because it has the potential to affect this code more acutely. How could it have a security consequence? Consider Listing 6-32. Listing 6-32. Structure Padding in a Network Protocol

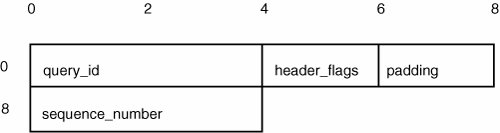

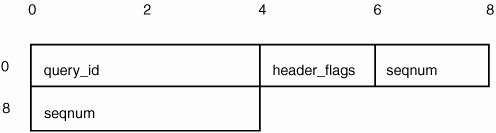

On a 32-bit big-endian system, the neTData structure is likely to be laid out as shown in Figure 6-9. You have an unsigned int, an unsigned short, 2 bytes of padding, and an unsigned int for a total structure size of 12 bytes. Figure 6-10 shows the traffic going over the network, in network byte order. If developers don't anticipate the padding being inserted in the structure, they could be misinterpreting the network protocol. This error could cause the server to accept a replay attack. Figure 6-9. Netdata structure on a 32-bit big-endian machine Figure 6-10. Network protocol in network byte order The possibility of making this kind of mistake increases with 64-bit architectures. If a structure contains a pointer or long value, the layout of the structure in memory will most likely change. Any 64-bit value, such as a pointer or long int, will take up twice as much space as on a 32 bit-system and have to be placed on a 64-bit alignment boundary. The contents of the padding bits depend on whatever happens to be in memory when the structure is allocated. These bits could be different, which could lead to logic errors involving memory comparisons, as shown in Listing 6-33. Listing 6-33. Example of Structure Padding Double Free

If the structure padding is different in the two structures, it could cause a double-free error to occur. Take a look at Listing 6-34. Listing 6-34. Example of Bad Counting with Structure Padding

The size of hdropt would likely be 3 because there are no padding requirements for alignment. The size of hdr would likely be 8 and the size of msghdr would likely be 12 to align the two structures. Therefore, memset would write 1 byte past the allocated data with a \0. PrecedenceWhen you review code written by experienced developers, you often see complex expressions that seem to be precariously void of parentheses. An interesting vulnerability would be a situation in which a precedence mistake is made but occurs in such a way that it doesn't totally disrupt the program. The first potential problem is the precedence of the bitwise & and | operators, especially when you mix them with comparison and equality operators, as shown in this example: if ( len & 0x80000000 != 0) die("bad len!"); if (len < 1024) memcpy(dst, src, len);The programmers are trying to see whether len is negative by checking the highest bit. Their intent is something like this: if ( (len & 0x80000000) != 0) die("bad len!");What's actually rendered into assembly code, however, is this: if ( len & (0x80000000 != 0)) die("bad len!");This code would evaluate to len & 1. If len's least significant bit isn't set, that test would pass, and users could specify a negative argument to memcpy(). There are also potential precedence problems involving assignment, but they aren't likely to surface in production code because of compiler warnings. For example, look at the following code: if (len = getlen() > 30) snprintf(dst, len - 30, "%s", src) The authors intended the following: if ((len = getlen()) > 30) snprintf(dst, len - 30, "%s", src) However, they got the following: if (len = (getlen() > 30)) snprintf(dst, len - 30, "%s", src) len is going to be 1 or 0 coming out of the if statement. If it's 1, the second argument to snprintf() is -29, which is essentially an unlimited string. Here's one more potential precedence error: int a = b + c >> 3; The authors intended the following: int a = b + (c >> 3); As you can imagine, they got the following: int a = (b + c) >> 3; Macros/PreprocessorC's preprocessor could also be a source of security problems. Most people are familiar with the problems in a macro like this: #define SQUARE(x) x*x If you use it as follows: y = SQUARE(z + t); It would evaluate to the following: y = z + t*z + t; That result is obviously wrong. The recommended fix is to put parentheses around the macro and the arguments so that you have the following: #define SQUARE(x) ((x)*(x)) You can still get into trouble with macros constructed in this way when you consider order of evaluation and side-effect problems. For example, if you use the following: y = SQUARE(j++); It would evaluate to y = ((j++)*(j++)); That result is implementation defined. Similarly, if you use the following: y = SQUARE(getint()); It would evaluate to y = ((getint())*(getint())); This result is probably not what the author intended. Macros could certainly introduce security issues if they're used in way outside mainstream use, so pay attention when you're auditing code that makes heavy use of them. When in doubt, expand them by hand or look at the output of the preprocessor pass. TyposProgrammers can make many simple typographic errors that might not affect program compilation or disrupt a program's runtime processes, but these typos could lead to security-relevant problems. These errors are somewhat rare in production code, but occasionally they crop up. It can be entertaining to try to spot typos in code. Possible typographic mistakes have been presented as a series of challenges. Try to spot the mistake before reading the analysis. Challenge 1while (*src && left) { *dst++=*src++; if (left = 0) die("badlen"); left--; }The statement if (left = 0) should read if (left == 0). In the correct version of the code, if left is 0, the loop detects a buffer overflow attempt and aborts. In the incorrect version, the if statement assigns 0 to left, and the result of that assignment is the value 0. The statement if (0) isn't true, so the next thing that occurs is the left--; statement. Because left is 0, left-- becomes a negative 1 or a large positive number, depending on left's type. Either way, left isn't 0, so the while loop continues, and the check doesn't prevent a buffer overflow. Challenge 2int f; f=get_security_flags(username); if (f = FLAG_AUTHENTICATED) { return LOGIN_OK; } return LOGIN_FAILED;The statement if (f = FLAG_AUTHENTICATED) should read as follows: if (f == FLAG_AUTHENTICATED) In the correct version of the code, if users' security flags indicate they're authenticated, the function returns LOGIN_OK. Otherwise, it returns LOGIN_FAILED. In the incorrect version, the if statement assigns whatever FLAG_AUTHENTICATED happens to be to f. The if statement always succeeds because FLAG_AUTHENTICATED is some nonzero value. Therefore, the function returns LOGIN_OK for every user. Challenge 3for (i==5; src[i] && i<10; i++) { dst[i-5]=src[i]; }The statement for (i==5; src[i] && i<10; i++) should read as follows: for (i=5; src[i] && i<10; i++) In the correct version of the code, the for loop copies 4 bytes, starting reading from src[5] and starting writing to dst[0]. In the incorrect version, the expression i==5 evaluates to true or false but doesn't affect the contents of i. Therefore, if i is some value less than 10, it could cause the for loop to write and read outside the bounds of the dst and src buffers. Challenge 4if (get_string(src) && check_for_overflow(src) & copy_string(dst,src)) printf("string safely copied\n");The if statement should read like so: if (get_string(src) && check_for_overflow(src) && copy_string(dst,src)) In the correct version of the code, the program gets a string into the src buffer and checks the src buffer for an overflow. If there isn't an overflow, it copies the string to the dst buffer and prints "string safely copied." In the incorrect version, the & operator doesn't have the same characteristics as the && operator. Even if there isn't an issue caused by the difference between logical and bitwise AND operations in this situation, there's still the critical problem of short-circuit evaluation and guaranteed order of execution. Because it's a bitwise AND operation, both operand expressions are evaluated, and the order in which they are evaluated isn't necessarily known. Therefore, copy_string() is called even if check_for_overflow() fails, and it might be called before check_for_overflow() is called. Challenge 5if (len > 0 && len <= sizeof(dst)); memcpy(dst, src, len); The if statement should read like so: if (len > 0 && len <= sizeof(dst)) In the correct version of the code, the program performs a memcpy() only if the length is within a certain set of bounds, therefore preventing a buffer overflow attack. In the incorrect version, the extra semicolon at the end of the if statement denotes an empty statement, which means memcpy() always runs, regardless of the result of length checks. Challenge 6char buf[040]; snprintf(buf, 40, "%s", userinput); The statement char buf[040]; should read char buf[40];. In the correct version of the code, the program sets aside 40 bytes for the buffer it uses to copy the user input into. In the incorrect version, the program sets aside 32 bytes. When an integer constant is preceded by 0 in C, it instructs the compiler that the constant is in octal. Therefore, the buffer length is interpreted as 040 octal, or 32 decimal, and snprintf() could write past the end of the stack buffer. Challenge 7if (len < 0 || len > sizeof(dst)) /* check the length die("bad length!"); /* length ok */ memcpy(dst, src, len);The if statement should read like so: if (len < 0 || len > sizeof(dst)) /* check the length */ In the correct version of the code, the program checks the length before it carries out memcpy() and calls abort() if the length is out of the appropriate range. In the incorrect version, the lack of an end to the comment means memcpy() becomes the target statement for the if statement. So memcpy() occurs only if the length checks fail. Challenge 8if (len > 0 && len <= sizeof(dst)) copiedflag = 1; memcpy(dst, src, len); if (!copiedflag) die("didn't copy");The first if statement should read like so: if (len > 0 && len <= sizeof(dst)) { copiedflag = 1; memcpy(dst, src, len); }In the correct version, the program checks the length before it carries out memcpy(). If the length is out of the appropriate range, the program sets a flag that causes an abort. In the incorrect version, the lack of a compound statement following the if statement means memcpy() is always performed. The indentation is intended to trick the reader's eyes. Challenge 9if (!strncmp(src, "magicword", 9)) // report_magic(1); if (len < 0 || len > sizeof(dst)) assert("bad length!"); /* length ok */ memcpy(dst, src, len);The report_magic(1) statement should read like so: // report_magic(1); ; In the correct version, the program checks the length before it performs memcpy(). If the length is out of the appropriate range, the program sets a flag that causes an abort. In the incorrect version, the lack of a compound statement following the magicword if statement means the length check is performed only if the magicword comparison is true. Therefore, memcpy() is likely always performed. Challenge 10l = msg_hdr.msg_len; frag_off = msg_hdr.frag_off; frag_len = msg_hdr.frag_len; ... if ( frag_len > (unsigned long)max) { al=SSL_AD_ILLEGAL_PARAMETER; SSLerr(SSL_F_DTLS1_GET_MESSAGE_FRAGMENT, SSL_R_EXCESSIVE_MESSAGE_SIZE); goto f_err; } if ( frag_len + s->init_num > (INT_MAX - DTLS1_HM_HEADER_LENGTH)) { al=SSL_AD_ILLEGAL_PARAMETER; SSLerr(SSL_F_DTLS1_GET_MESSAGE_FRAGMENT, SSL_R_EXCESSIVE_MESSAGE_SIZE); goto f_err; } if ( frag_len & !BUF_MEM_grow_clean(s->init_buf, (int)frag_len + DTLS1_HM_HEADER_LENGTH + s->init_num)) { SSLerr(SSL_F_DTLS1_GET_MESSAGE_FRAGMENT, ERR_R_BUF_LIB); goto err; } if ( s->d1->r_msg_hdr.frag_off == 0) { s->s3->tmp.message_type = msg_hdr.type; s->d1->r_msg_hdr.type = msg_hdr.type; s->d1->r_msg_hdr.msg_len = l; /* s->d1->r_msg_hdr.seq = seq_num; */ } /* XDTLS: ressurect this when restart is in place */ s->state=stn; /* next state (stn) */ p = (unsigned char *)s->init_buf->data; if ( frag_len > 0) { i=s->method->ssl_read_bytes(s,SSL3_RT_HANDSHAKE, &p[s->init_num], frag_len,0); /* XDTLS: fix thismessage fragments cannot span multiple packets */ if (i <= 0) { s->rwstate=SSL_READING; *ok = 0; return i; } } else i = 0;Did you spot the bug? There is a mistake in one of the length checks where the developers use a bitwise AND operator (&) instead of a logical AND operator (&&). Specifically, the statement should read: if ( frag_len && !BUF_MEM_grow_clean(s->init_buf, (int)frag_len + DTLS1_HM_HEADER_LENGTH + s->init_num))This simple mistake could lead to memory corruption if the BUF_MEM_grow_clean() function were to fail. This function returns 0 upon failure, which will be set to 1 by the logical not operator. Then, a bitwise AND operation with frag_len will occur. So, in the case of failure, the malformed statement is really doing the following: if(frag_len & 1) { SSLerr(...); } |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 194