Chapter 2: The StrategicNegotiation Process

In the last chapter I argued that a blueprint exists that can be applied to literally any negotiation, that by using the Strategic Negotiation Process you can fill in the details of that blueprint, and that by the time you’ve done that, you’ll have all you need to close any deal. The obvious questions then are these: Exactly what is this blueprint, what is the process, and how does the process work? In this chapter I provide the answers to the first two questions, and in the chapters that follow the answer to the third.

THE BLUEPRINT

Our research and global fieldwork have shown that virtually every negotiation, regardless of who’s conducting it or where it takes place, can be blueprinted in exactly the same way. This is extremely important, because we also found that everything that takes place in the course of a negotiation—the planning and the research as well as all the tactics used in the final face-to-face meeting—is ultimately driven by that blueprint. But what is it? It’s essentially a picture of the entire negotiation, a picture that can be determined by answering two questions for those on both sides of any deal:

-

What are the consequences if we do not reach agreement?

-

What items are likely to be included if we do reach agreement?

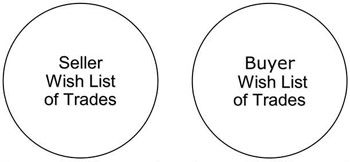

To answer these questions, however, we must first go back to some very basic concepts about negotiating. In most negotiations, both sides have a separate “Wish List” of what they would like to achieve in the negotiation. Looking at it graphically, these two Wish Lists could look like this:

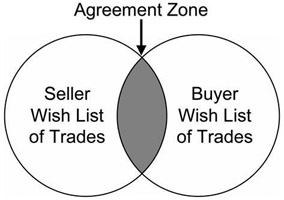

Although neither side in most negotiations gets exactly what it wants in the final deal, if the two sides do come to an agreement, both get at least some of the things that were on their Wish Lists. Such a situation could be represented like this:

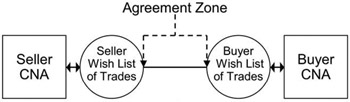

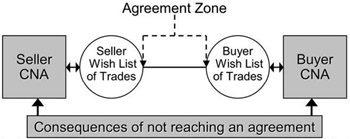

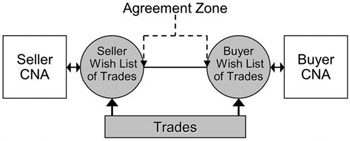

But regardless of whether the two parties ever come to an agreement, there is a blueprint that can be applied to the situation. That blueprint looks like this:

In the middle of the blueprint are the two Wish Lists and between them the Agreement Zone—that is, the place where the two sides meet if they come to an agreement. However, there is always, for both sides, an alternative to reaching agreement with the other side, which we refer to as the Consequences of No Agreement (CNA) and which are shown on either side of the blueprint.

What Are the Consequences of No Agreement?

You may never have used the expression Consequences of No Agreement, but the chances are that you’ve thought about them. After all, you know that something is going to happen if you don’t make a deal. As the seller, your Consequences of No Agreement—your alternative to making a deal—is most likely going to be losing the sale. Your customer, on the other hand, generally has three possible alternatives to reaching agreement with you. He or she can (1) go to a competitor, (2) build the solution himself or herself, or (3) do nothing. It’s only when negotiators obtain something that’s at least marginally better than their alternative that they prefer agreement to impasse.

Understanding the Consequences of No Agreement, both for yourself and your customer, is easily the most important aspect of constructing a blueprint of a negotiation. The reason is that, in any negotiation, the other side always sees your offer as a gain or loss based on its perception of the consequences of not reaching agreement with you. Simply put, if the other side believes that making a deal with you will be to its benefit, it will do it. But if it believes that it’ll be better off if it doesn’t make a deal with you, regardless of the alternatives you’re going to lose the sale.

Note that I said the other side makes a decision based on its perception of the consequences. The truth is that in any given negotiation, more often than not, one or both sides haven’t taken the time to analyze their true Consequences of No Agreement, or they have but have misdiagnosed them. In either case, even if one or the other side is putting a great offer on the table, chances are the two sides won’t be able to reach agreement if the consequences are misdiagnosed or misunderstood. That’s one of the reasons it’s so important to answer the first question I posed above—What are the consequences if we do not reach agreement?—by accurately determining those consequences. Making that determination is the first step in blueprinting a negotiation as well as the first step in the Strategic Negotiation Process. Moreover, as you learn how to use our process in the following chapters, you’ll learn how to diplomatically educate those on the other side about their true Consequences of No Agreement. And as you no doubt already understand, most customers will be much more likely to close a deal if they can see that your offer is better than their alternative—that is, their Consequences of No Agreement.

What Items Are Likely to Be Included If We Do Reach Agreement?

Obviously, some negotiations—probably even most—end in agreement rather than impasse. But in order to reach such agreement, in order to fill in the rest of the blueprint, it’s necessary to answer the second question I posed: What items are likely to be included if we do reach agreement? In the course of our consulting, we see people involved in very complicated negotiations that include a variety of different items, such as price, length of agreement, service, payment terms, legal terms, volume, and so on. Even so, when we ask them to tell us what the negotiation is about, they often just say, “Price.” Bear in mind that these are not young, inexperienced negotiators but rather seasoned executives who may have negotiated hundreds of deals but still fall prey to this common mistake. As I’ve already noted, except for commodities, of which there are very few, price is never the only item in a negotiation, and unless you know what all the items are going to be, unless you answer the question I raised above, you won’t be able to negotiate as successfully as you should.

Here’s an example. At the end of the first year of my partnership with Max Bazerman, I realized that as a result of the terms of our agreement, Max had received a larger portion of the company’s profits than I had. This was not what I’d expected, and although I didn’t really need the additional cash, my ego was involved, so I wasn’t happy about it. Unfortunately, the only option was to try to renegotiate the deal with him. And that made me more than a bit nervous because Max is, after all, the master. In any case, I called Max and asked him to lunch.

During lunch we discussed a number of items, and it was only when we got near the end of the meal that I brought up the subject of our agreement. “Max,” I said, “I’m not making enough money here.” Leaning back in his chair, he thought for a moment, looked me in the eye, and said, “So you want some of mine.” Although I was, to put it mildly, stunned by his response, I quickly realized what I’d done. I had asked Max to literally reach into his wallet and give me some money back. If he had agreed to do so, I may have made some money, but it would have been at his expense, and, on balance, all we would have accomplished was to “rearrange value.” That is, the partnership would have gained nothing by it. And it was essentially because I had, however unwittingly, broken a very important rule of negotiating: Never negotiate one thing. It’s only when you discuss more than one thing that you can create true and measurable business value in a negotiation.

When I regained my composure, I said to Max, “No, that’s not what I said, although I guess it is what I meant.” And Max, to his credit, responded in the masterly way I should have expected of him. He suggested two alternative arrangements between us. In the first, I would get less cash flow than I had been getting at the time, but I would, in turn, get some of his equity. In the second, although I would have additional cash flow, I would give up some of my equity. As it happened, at the time Max was looking for some additional cash himself, and because I was otherwise satisfied with the arrangement, we restructured our deal using the first alternative.

The point here is that rather than negotiate over just one issue— money—we redefined the negotiation in terms of a couple of simple variables that had different levels of importance to the two of us. That is, it was less important to Max that he maintain his share of the partnership’s equity as long as he could have greater cash flow. And at the same time, it was less important to me that I have increased cash flow if I could have more equity in the business. In other words, it was the fact that we had something we could trade that made it possible for us to make a deal. In this case, the Consequences of No Agreement would have been either to break up our partnership or to continue it with some bad feelings on both sides. Instead, by trading we both came out of the negotiation better off than we would have if we hadn’t reached an agreement.

In theory, determining what items should be part of the final deal should be a very simple exercise. However, because of financial pressures, political pressures, lack of planning, and a lot of old school negotiation tactics, it’s not unusual to see situations in which neither side has a clear idea of what it really wants from a negotiation. Of course, both sides always have some idea of what they’re looking for—at least one or two items, but often that’s all. That’s not a problem if you’re negotiating over a commodity, but the less commodity-like your product or service is, the more important negotiation skills become and the more opportunity there is for creating value for both sides. The reality is that the heart and soul of business negotiation is trading. And to trade properly, a world-class negotiator has to understand not only what all the variables are in a business deal but also what’s most to least important to both sides. In the next few chapters, as you learn how to blueprint a negotiation using the Strategic Negotiation Process, you will become that kind of world-class negotiator.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 74