MANAGING INTERNAL CONFLICTS

A key step in achieving a balance between attaining results and satisfying employees' needs is resolving conflicts using a win-win orientation. A popular myth with executives is that they must be tough to be successful. Although some leaders have gained notoriety by being ruthless, ultimately these top-floor bullies fail because they cannot connect to the spirit of the people who do the work and accomplish the results.

Leadership surveys consistently reveal that the most successful bosses achieve results through connectivity, that is, by listening to people, building partnerships, and resolving internal strife, rather than creating it. While it's true that leaders from time to time must make tough, unpopular decisions, the manner in which they make and implement those decisions will impact their effectiveness. Using a win-win orientation, you may be surprised to discover that achieving results and building a loyal workforce does not necessarily involve a conflict. Increasing employee loyalty could be as easy as listening to employees and acting on their best ideas, an approach that can often bring about exactly the business results you want and need.

Inherent Styles of Conflict Resolution

How leaders act to reduce internal strife depends a great deal on their primary style of conflict resolution. Each of us tends to fall back on an inherent conflict resolution strategy—call it a "default" approach to resolving conflicts. We have identified four inherent styles of conflict resolution:

-

Evader: avoids conflicts as much as possible

-

Fighter: competes with others to get his or her way

-

Compromiser: identifies what can be given up to meet halfway

-

Harmonizer: gives into the demands of others to keep peace

Each of these conflict resolution styles is based on a form of the fight-or-flight response. This primitive instinct has its uses—after all, we're still around, aren't we?—but it also has limitations. Each style logically produces either a win-lose or a lose-lose outcome; such divisive consequences create either winners and losers or just losers. When leaders apply their inherent, or default, style—the one they often revert to under stress—it's no wonder so many revenue-enhancing strategies end up with someone, and possibly everyone, losing.

Evader

Executives with an Evader style try to avoid conflict with employees. To do this they use a simple strategy: they avoid input from others. If there's no input, then there can be no disagreement. But leaders also lose valuable insights and contributions from employees as well as making employees feel like their work is not valuable. One of the authors once consulted on competency-based selection with a European financial services company in which employees were officially forbidden to communicate with executives. Not only were employees not allowed to speak with anyone whose office was on the top floor, but they were also barred from sending memos to executives and banned from even visiting the top floor (an edict enforced by a stone-faced security guard posted by the elevator). That company is no longer in business today. However, an Evader's defenses against input are generally much more subtle than security guards stationed to shoo people away.

Fighter

Fighters also avoid input from others, but they do it in a more aggressive way. Fighters become so convinced they are right that they become combative whenever they are challenged. If you disagree with them, you are either wrong, stupid, or most likely both! Not the most effective strategy for encouraging input from others. We have all run into this kind of "my way or the highway" manager. In a restructuring engagement in a large American utility, one of the authors encountered a senior vice president determined to ram through an organizational design that he had thought up on a two-hour flight from the company's nuclear plant back to headquarters. He pressed, he pushed, he prodded, and he said no to each and every alternative idea and suggestion. He drove his concept so hard that employees literally rebelled, organized, and forced their way into a board meeting carrying protest signs (as opposed to pitchforks and torches), having of course already alerted the local news media to the impending confrontation. When you push people, people push back.

Compromiser

Being a Compromiser might sound like a positive strategy, but often Compromisers give up on critical issues in order to reach agreement. As a result, they stall having to make tough decisions and often have to deal with bigger problems down the line. In observing a high-level team chartered to restructure the human resources function of a large international manufacturing company, one of the authors got to see firsthand the downstream impact of Compromisers at work. The company had a history of adversarial negotiations with its bargaining units, and so many of its senior HR leaders had become accustomed to seeing compromise as the surest way to gain agreement: the bargaining unit gets a little of this, the company gets a little of that. A zero-sum game in spades. In working with line team members to realign their function, these leaders could not break free of a compromise mentality. As a result, just to be done with it all, the structure team compromised and proposed irrational splits in HR functions, tantamount to Solomon's suggestion of bisecting the baby. No one was happy with any of it, and the CEO pitched most of the team's recommendations and decided himself how things were going to be going forward.

Harmonizer

Harmonizers are the extreme version of the Compromisers. They typically dislike all conflict and would rather give in to others, even at their own expense, than endure the pain that conflict causes them. On the opposite end of the scale from Fighters, Harmonizers would rather just say yes. On a project to build a leadership competency model for a global agricultural products company, one of the authors bumped into a finance and accounting senior manager who dreaded butting heads with the line managers served by her department. To keep these line managers at bay, she had gotten in the habit of routinely saying yes to almost every demand made of her by the senior line leaders, so much so that at one point her staff members, unbeknown to her, spoke of the finance and accounting department as having "thirty-eight number one priorities and no number two-through-ten priorities." Worse for her staff, some of her commitments to provide certain finance and accounting services and reports for one group of senior line leaders contradicted other agreements she had made to please another group of senior executives. The situation was not as bad as having to keep two sets of books, but it was close. The last we heard, that finance and accounting manager had been forced to take a buyout and been replaced with someone who had been able to negotiate the clump of thirty-eight number one priorities down to a much more manageable pod of seven.

The Negotiator Style: Setting the Stage for Win-Win Outcomes

The only style that can produce a win-win outcome is the Negotiator style. Its premise is that to end conflict successfully you must attempt to meet everyone's highest-priority needs. To accomplish this task, leaders must first understand all aspects of the business—from both customer and employee perspectives—using their self-disclosure and feedback skills. They then prioritize the business needs along with employee needs and systematically work to satisfy the key issues for both sides.

While this technique might sound impossible, it's not, and it helps to adopt this strategy in the beginning. When faced with a decision about a proposed revenue-enhancing strategy, you might consider some steps that may at first seem counterintuitive. For example, you might naturally want to be secretive, consulting with a small group of close advisors and planning your course of action with little or no employee input. Instead, we suggest that you begin by opening communication with employees. Talk about the financial and business situation openly and candidly. Employees probably already know what's happening, anyway. Ask for feedback. When you share problems with employees and ask them for help, you'd be amazed at what people can do to conserve resources, create a new product or service, or improve an existing process.

Keep the communication loop open. Tell people what you know—or as much as you can legally tell them—and ask for comments, questions, and concerns. When people feel like they are getting the straight story, trust, credibility, and cooperation grow. Finally, be aware of your conflict resolution style. During times of stress, you will naturally slip into your inherent style. Therefore, it is critical to know and understand this style and to monitor your behavior. If your inherent style encourages a win-lose scenario, or a lose-lose outcome, you will damage the trust and loyalty of your best assets, your employees. Which of the following best describes how you usually go about handling conflicts?

EXERCISE 4: Conflict Resolution Style Descriptions

Directions:

Read the five descriptions of conflict resolution styles below. What is your predominate style when you are in an emotional situation?

-

"I don't like conflicts, and I try to avoid them. I would rather not be forced into a situation where I feel uncomfortable or under stress. When I do find myself in that kind of situation, I say very little, and I leave as soon as possible."

-

"To me, conflicts are challenging. They're like contests or competitions— opportunities for me to come up with solutions. I can usually figure out what needs to be done, and I'm usually right."

-

"I try to see conflicts from both sides. What do I need? What does the other person need? What are the issues involved? I gather as much information as I can, and I keep the lines of communication open. I look for a solution that meets everyone's needs."

-

"When faced with a conflict or even a potential conflict, I tend to back down or give in rather than cause problems. I may not get what I want, but that's a price I'm willing to pay for keeping the peace."

-

"I want to resolve the conflict as quickly as possible. I give up something I want or need, and I expect the other person to do the same. Then we can both move forward."

Interpretation

If you chose description 1 as most characteristic of yourself, your conflict resolution style is Evader, a lose-lose strategy. When one partner avoids a conflict, neither partner has an opportunity to resolve it. Both partners lose.

If you chose description 2, your conflict resolution style is Fighter, a win-lose or lose-win strategy. Either you win and your partner loses, or you lose and your partner wins. It's the survival of the fittest. But conflicts are not contests, and this style precludes the possibility of finding a fair solution.

If you chose description 3, your conflict resolution style is Negotiator, a win-win strategy. Both you and your partner have a chance to express needs and resolve the conflict in a mutually acceptable way. While this strategy may sound simple, it's actually the most difficult to use. It requires each of you to articulate, prioritize, and satisfy your own needs while also addressing the other person's needs.

If you chose description 4, your conflict resolution style is Harmonizer, a lose-win strategy. You lose because your needs aren't met. Your partner's needs are met, but the partnership suffers because you eventually become resentful and unsatisfied.

If you chose description 5, your conflict resolution style is Compromiser, a lose-lose strategy. Both you and your partner give up something you need just to make the conflict "go away." Invariably, you end up addressing the same issues later.

Try the quick Win-Win Assessment (Exercise 5) to determine your primary (default) style of conflict resolution. If you would like to take a more detailed win-win assessment, go to Chapter 3 in The Partnering Intelligence Fieldbook by Stephen M. Dent and Sandra M. Naiman.

Moving from a Culture of Individuals to a Culture of Negotiators

Our caveman ancestor Urg was smarter than you think. He may not have been able to articulate his decisions, but that doesn't mean he wasn't always calculating the odds. If he were surprised by a sabertooth tiger and happened to have his spear with him, he might hold his ground. But he was also just as likely to get out of there as fast as his feet would carry him. This fight-or-flight response governed Urg's life—the survival instinct was the only intelligence he needed.

EXERCISE 5: Win-Win Assessment

Directions:

-

Begin by thinking of the kinds of conflicts you encounter.

-

On a scale of 1-6, rate each of the statements below based on how you tend to react to those conflicts. Enter your score for each in the shaded box to the right of the statement.

-

Enter the column totals at the bottom.

| 1 = Strongly Disagree | 2 = Disagree | 3 = Somewhat Disagree |

| 4 = Somewhat Agree | 5 = Agree | 6 = Strongly Agree |

| A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Total Score |

Scoring:

Compare the total scores of each column. Your highest score indicates your preferred style of conflict resolution. Your second-highest score is your secondary, or backup, style.

-

Column A = Evader

-

Column B = Harmonizer

-

Column C = Compromiser

-

Column D = Fighter

What is your conflict resolution style?_________________________

What is your secondary conflict resolution style?______________

But before we get too comfortable with how far we've come, consider that people today are still ruled by this primal instinct. When confronted with conflict, most of us revert to fight or flight. Of course, over time this response has evolved and become more sophisticated. Even the most contentious boardroom battle doesn't get settled with clubs and shields, although we do occasionally read reports of fisticuffs. Instead of fighting with weapons, we fight with words, or we wield power and influence to get our way. Instead of physically retreating, we might become resistant to change, or settle for mediocrity, or staunchly defend the status quo.

The problem with these tactics is that they create a culture of winners and losers instead of a culture of overall achievement. One of the authors recently attended a board meeting at which team members were reverting to the flight-or-fight response in a way that was ultimately hurting the organization. You would have thought it was back in Urg's day, when the law of the land was eat or be eaten. How do we break free from this programming? Under stress our instincts will lead us to do what is most familiar, but our Partnering Intelligence can help us find solutions that benefit everyone. As we'll see, the answer lies in using our win-win orientation.

Win-Win Orientation Team Profile

Greg is the president of a small Midwestern firm that manufactures medical devices. His executive team consists of Kim, the CFO; Chris, the head of marketing and sales; and Mary, who handles research and development. These executives pride themselves on being nice people who have strong values and ethics and are easy to do business with. However, their work together is being hampered by underlying interpersonal conflict.

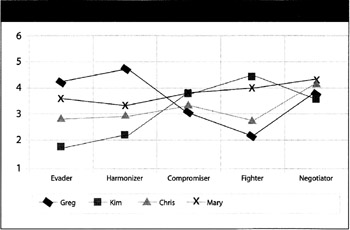

Recently Greg asked us for help. When we interviewed the team, it became clear they were having problems resolving conflict. They couldn't agree on anything important; they were avoiding each other; and they stalled on crucial decisions behind a smoke screen of "needing more information." On the surface they were polite to each other, but Mary said that sometimes "you could cut the atmosphere in our meetings with a knife." We began by administering an assessment similar to the one in Exercise 5. Each team member took the assessment individually. The Win-Win Orientation Team Profile shown in Figure 10 represents the results and helps explain why this team was having a problem resolving its issues.

Figure 10: Win-Win Orientation Team Profile (Sample)

Each of the first four styles—the Evader, the Harmonizer, the Compromiser, and the Fighter—stems from the fight-or-flight response. These are the inherent styles of conflict resolution. The Negotiator style, however, is not a natural response. It can only be learned, and it is this style that is so vital to organizational success. The inherent styles result in either a win-lose or lose-lose outcome, but the Negotiator's primary objective is to create a win-win outcome based on prioritized needs.

The team members with high scores in a particular area are more likely to use that style when resolving conflicts. Conversely, a low score means they are less likely to use that style. To analyze the team profile, look at the highest score in the inherent styles. The style with the highest score represents the team member's primary style of conflict resolution. The style with the second highest score represents their secondary or back-up style.

A Quick Analysis

Many people who take the Win-Win Orientation Assessment in The Partnering Intelligence Fieldbook (Chapter 3) assume they use a win-win orientation in their dealings with team members. They can all point to times when they used needs-based problem solving similar to the Negotiator style. What they often forget are all the other times when they reverted to their inherent style. The problem is that conflict creates an emotional state. No matter how cool and calm you think you are, when you're in conflict you are influenced by your emotions, and your emotions are responsible for triggering your inherent style.

Looking at Figure 10 and starting with Greg, the president, we can see that his primary style of conflict resolution is Harmonizer. Harmonizers are uncomfortable with conflict. Their managing strategy is to give in to other people's needs to keep the peace. While this seems like a good strategy, over time all that giving in can cause the Harmonizer to be resentful. This bitterness can result in passive-aggressive behavior—such as undermining people because the individual doesn't feel comfortable confronting them in the first place. Greg's secondary style is Evader, which creates a difficult situation for him and his team. When he has a high need but can't harmonize with his direct reports, he avoids the conflict entirely and makes decisions on his own. This tactic alienates his team and intensifies the conflict.

Kim, the CFO, is a classic Fighter. He turns every conflict into a competition, one he plans on winning. Unlike Harmonizers, Fighters are convinced that they're always right, and they will do whatever it takes to win. Kim's secondary style is Compromiser. When he knows he can't win outright, he'll give something up to reach an agreement.

As noted by the relatively straight line, Chris from Sales and Marketing takes a fairly balanced approach to resolving conflict. She moves back and forth between Compromiser and Harmonizer, but she will also become a Fighter if the issue is important enough to her.

Mary, the head of R&D, is also a Fighter, a style that has created an interesting dynamic with Kim. The two of them are always wrestling over the cost-benefit analysis of a particular project. When she and Kim go at it, the other team members tend to fade into the woodwork until the whole thing blows over. The rest of the team looks to Greg to resolve the issue, but he always seems to give in (usually to Kim if you ask Mary, or to Mary if you ask Kim), or he evades the whole issue entirely.

Getting to a Win-Win Outcome

The problems these conflicts are causing the team are imposing. With two Fighters and two non-Fighters, there is often a "Battle of the Titans," with the non-Fighters sitting on the sidelines, cringing. Add a CEO who is unwilling to engage in conflict at all and it only makes matters worse. What can they do?

First, each team member must strive to understand each other's inherent style. It's a big step, but many teams find that it's actually a relief to talk about the mechanics behind the conflict. Next, the team must acknowledge and understand how emotions are pushing them to revert to these inherent styles. Greg must break through his veil of denial, while Mary and Kim have to stop looking at each other as competitors and start acting as partners. Chris can use her fairly balanced approach to help coach the other team members toward taking the next step, which is moving to the Negotiator style.

The good news is that the assessment indicates that each team member has an intellectual understanding of the Negotiator style. To fully embrace this win-win style, the team will have to consciously decide that they do not want to react to conflict based on emotions. Once they have committed to this collaborative approach, they can take the following steps to achieve a new level of cooperation, commitment, and achievement:

-

Acknowledge openly that there is a conflict

-

Determine the source of the conflict: Is it based on information, perception, facts, values, or methodology?

-

Understand what they consider to be important in resolving the conflict; each team member should write down his or her needs and prioritize them

-

Use self-disclosure and feedback skills to share the information among team members and the impact others' needs have on them

-

Negotiate the resolution based on getting each team member's most important needs met

Getting to a win-win outcome can be time consuming. But the alternative, creating losers, will ultimately cause you to waste more time and resources than spending the energy up front to resolve the issue and get it behind you. The first time you create a loser on your team, you've set up the dynamic for ongoing conflict.

Leadership Responsibilities

Partnering cultures accomplish conflict resolution and problem solving in a way that enables everyone, regardless of style, to be heard at the table. Everyone has an important contribution—information or connections—that makes their input vital. Using any style other than Negotiator limits the opportunity for everyone to make a contribution. One of the most effective actions you can take to foster the use of the Negotiator style is to set the stage by making it comfortable for people to move to that style:

-

Set the tone, in words and actions—let members of the team know that, despite all the inherent styles, you will strive to use the Negotiator style

-

Educate people on their inherent style—this insight provides them with awareness and context as they work with others

-

Hire smart partners who understand the Negotiator style and can move toward it

-

Measure the impact of conflict on the organization and get members to make resolving it an important issue

Measuring Your Win-Win Orientation

We have seen just the beginning of how the Win-Win Orientation Assessment can help your team get on the right track from the start. But the first step in becoming a great Negotiator is awareness. Knowing your team's win-win orientation sets the stage for resolving future conflicts quickly by helping you understand each member's style and providing a context for discussion about conflict styles in general. It is a crucial step toward creating a successful partnering culture. Everyone can agree that collaboration is critical, but how do you measure something as intangible as collaboration? The most direct method we have found is to simply ask people. Survey employees about how well they collaborate with others and how well others collaborate with them. Once you have the baseline measurement, you can then find out how these skills improve over time.

The best secondary indicator of a win-win orientation is how many conflicts escalate to the point where they need to be resolved at the executive level. People who are using a win-win orientation tend to solve their own problems at the lowest organization level possible. If problems keep getting passed up the chain of command for resolution, you know that people aren't collaborating. Establish a measurement for how many issues get escalated to a specific level within your organization. Look for trends. As you track the data, you may discover that one department, group, or person has consistent difficulty collaborating.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 94