Determining What to Audit

One of the most important tasks the internal audit department will perform is determining what to audit. In Chapter 1 we discussed such things as early involvement, informal audits, and self-assessments. This is not the sort of thing we're talking about now. Now we're referring to traditional, formal audits-the kinds that have teams of auditors working on them, producing workpapers, audit reports, lists of issues, and action plans for resolving those issues.

It is important that your audit plan focuses your auditors on the areas that have the most risk and on areas where you can add the most value. You have limited resources, and you have to be efficient and effective in how you use them. You have to spend your IT audit hours looking at the areas of most importance. This should not be done by arbitrarily pulling potential audits out of the air but instead should be a logical and methodical process that ensures that all potential audits have been considered.

Creating the Audit Universe

One of the first steps to ensure an effective planning process is to create your IT audit universe. You must be aware of what audits you potentially might perform before you can rank them. There are multiple ways to slice the IT universe, and none of these is right or wrong. What is important is to figure out a way to slice the environment that will allow for the most effective audits.

The Audit Universe-Centralized IT Functions

It is advisable to determine what IT functions are centralized and place each of those centralized functions on your list of potential IT audits (Table 2-1). For example, if you have a central function that manages your Unix and Linux server environment, then one of your potential audits might be a review of the management of that environment. This could include administrative processes such as account management, change management, problem management, patch management, security monitoring, and other such processes that would apply to the whole environment.

| Unix and Linux server administration | Central help desk |

| Windows server administration | Database management |

| Wireless network security | Telephony and voice over IP |

| Internal router and switch management | Mobile services |

| Firewall/DMZ management | IT security policy |

| Mainframe operations |

One example might include a review of the security of the baseline the centralized Unix and Linux function uses for deploying new servers. This audit could cover all those processes that apply to the whole Unix and Linux server environment. Then, if the financial auditors' audit plan calls for an audit of a particular financial application that resides on a Unix server, your participation in that audit could consist solely of auditing the security of that specific server without having to spend time understanding the processes for managing that server (which were covered already in your centralized audit).

Of course, each company will centralize these sorts of core IT functions to differing degrees. It is important to understand the environment well enough to determine what functions are centralized and add those functions into your audit universe. Audits of those sorts of functions form a baseline that will speed up the rest of your audits. As you perform other audits, you can scope out those centralized functions that have already been audited. For example, let's say that you perform audits of the IT environment at each site, but the network configuration and support are centralized. It would be very inefficient to talk to the remote group about their processes during each and every site audit. Instead, you should perform one audit covering their processes and then scope that area out of your site audits.

The Audit Universe-Decentralized IT Functions

After creating a list of all the company's centralized IT processes, you can determine the rest of your audit universe. One potential way to slice the rest of the universe is to have one potential audit per company site. These audits could consist of reviewing the decentralized IT controls that are owned by each site, such as data center physical security and environmental controls. Server and PC support also may be decentralized at your company. The key would be to understand what IT controls are owned at the site level and review those. It may be necessary to get more granular than this and have numerous potential audits at each site. It all depends on the complexity of the environment, the breakup of the organization, and your staffing levels. You will have to determine what is most effective in your environment.

| Note | Getting your hands wrapped around what potential audits are in your universe is critical to being effective. Perhaps the best way to scope the breadth of possible audits is to meet with the company's IT managers to understand how IT responsibilities are divided and determine what IT functions are centralized and decentralized in your company. |

The Audit Universe- Business Applications

You also might have a potential audit for each business application. You will have to determine if it is more effective to have these audits in the IT audit universe or in the financial audit universe. In many ways, it makes the most sense to have these audits be driven by the financial auditors. For example, they are probably in the best position to determine that it is time to perform an audit of the procurement process. If they do make that decision, then they can approach you and have you determine the relevant system aspects that should be included in the procurement audit (such as a reviews of the server on which the procurement application resides, the system's software change controls, the systems disaster recovery plan, etc.).

The Audit Universe- Regulatory Compliance

Depending on the services or goods your business provides, you might be responsible for ensuring compliance with certain regulations. Common examples include auditing compliance with Sarbanes-Oxley, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), and Payment Card Industry (PCI) regulations and standards. You might have a separate audit in your audit universe for testing compliance with each relevant regulation.

| Note | A good source for ensuring that you have considered all significant areas of IT governance is to reference the control objectives for information and related technology (CoBIT) framework. This framework defines the high-level control objectives for IT, and although your planning always should be tailored to the specifics of your company's environment, CoBIT can be a good reference in creating your audit universe. We will discuss CoBIT in more detail in Chapter 13. You also can learn more about CoBIT online at http://www.isaca.org. |

Ranking the Audit Universe

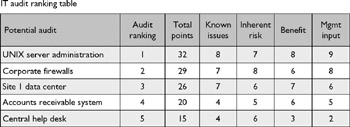

Once you've created your IT audit universe, you must develop a methodology for ranking those potential audits (Figure 2-2) in order to determine your plan for the year (or quarter or month or whatever your schedule is). There are all kinds of factors you can include in this methodology, but following are some of the essential ones:

Figure 2-2: Example audit ranking table.

-

Known issues in the area. If you know there are problems in the area, it should be more likely that you perform an audit there.

-

Inherent risk in the area. Maybe you don't know of any specific problems in the area, but your experience tells you that the area is one that is prone to problems. If so, it should be more likely that you perform an audit there. For example, maybe you consistently find significant issues when auditing site-level IT controls supporting a particular manufacturing activity. This experience would lead you to feel that there's higher inherent risk in that area, steering you to perform similar audits at other sites, even if you're not aware of any specific problems at those sites.

-

Benefit of performing an audit in the area. This is a critical factor that is not always taken into account. You should consider the likelihood that performing an audit in the area will add value to the company. This provides an offset of sorts to the first item in this list. For example, there might be an area where you know there are issues. However, maybe management is already aware of and is addressing those issues. If this is the case, it adds no value for you to go in there and tell management about all the problems they're already in the process of fixing. Instead of auditing it, consider being part of the team that is developing solutions to fix the problem (as discussed in Chapter 1). You also have to consider the importance of an area to the company. For example, maybe you know that there are problems with the system used to order meals for internal meetings. Your ranking model needs to take into account the fact that this system just isn't very important to the overall success of the company.

-

Management input. In Chapter 1 we discussed the importance of developing and maintaining good relationships with IT management. When those relationships are healthy, the input of IT management should be a large factor in your decisions as to what to audit. If your chief information officer (CIO) and/or key members of his or her leadership team have a concern in an area and want you to audit it, then that input should weigh heavily in your decision process. In fact, if those relationships are healthy and you're doing a good job of maintaining contact throughout the year, then your audit plan almost should create itself. You'll already be aware of major changes in the environment and of significant concerns, meaning that your planning process can just be a confirmation of the discussions you've been having throughout the year. Note that this factor might influence the others. For example, if management is encouraging you to perform an audit, it is likely because managers know of problems in the area, which might lead you to increase your rating of the first factor (known issues in the area). It also might lead you to believe that you can add value by performing the audit, leading you to potentially increase your rating of the third factor (benefit of performing an audit in the area).

Other factors can be included in an audit ranking model, but these are the four that are absolutely essential. Other factors can be added based on the environment at your company. Also, the environment at your company may lead you to weight some of those factors more heavily than others. As an example of how the ranking model would work, you might decide to rank each factor from 1 to 10. If the CIO and the entire leadership team are encouraging you to do an audit, then the management input factor might get a 10. However, if it's an area where you do not feel there is much inherent risk, you might give that factor a 5. And so on until you have assigned a point value to each factor for each potential audit in your audit universe. You also might decide that, for example, the "known issues" factor needs a higher weighting than the others, so you might count that factor double. The key is to have your universe of potential audits defined and then some process that helps you rank the relative importance of performing each of those potential audits.

| Note | See Chapter 15 for information covering detailed risk analysis techniques. |

There are some companies that place a large emphasis on rotating audits, where each audit is on a specific schedule. This can be a valid way to ensure that all critical systems and sites are audited regularly; however, rotation schedules always should be a guideline and not a firm rule. You always should consider what is the most important area for you to audit today based on factors such as those just mentioned. A rotation schedule should not serve as an excuse for you to turn your brain off and ignore known problems and the input of IT management. It is critical to reserve the right to ignore the rotation schedule in order to ensure that you are hitting the areas where you can add the most value to the company. If rotations are a big part of how your audits are scheduled, you might consider adding rotation schedule as a factor in your audit ranking model. In this way, if an audit is due in the rotation (or past due), it is more likely to make the plan.

Of course, there may be some audits that you are required to perform on an annual basis per regulatory requirements (such as Sarbanes-Oxley compliance). Such audits obviously do not need to be ranked.

Determining What to Audit-Final Thoughts

Once you have performed your ranking, you will need to estimate the resource requirements for each potential audit. This will allow you to determine the cut line for your audit plan (since you should already know what resources are available to you). It also will allow you to show management which audits you will not have time to get to, which can lead to healthy discussions about the appropriateness of audit staffing levels and/or the need to consider cosourcing options.

In summary, before you can feel comfortable that you're auditing the right things, you must determine your universe of potential audits and then develop a methodology for ranking those audits. Once you have determined what you will be auditing, you then obviously need to execute each audit in the plan. The rest of this chapter is devoted to discussing the methodologies for doing so.

EAN: N/A

Pages: 159