Summary - Key Lessons for Managers and Consultants

-

Improving operational business performance has long been, and still remains, the bedrock of consulting.

-

The best operational consulting has five characteristics:

-

- being able to distinguish the precise cause of a problem from its symptoms;

-

- appreciating the constraints the client is under; - bringing management tools and techniques that are new to the client and which help resolve the issue;

-

- ensuring that the consultants' skills are passed on to clients; - ensuring that the changes made are sustainable.

-

-

However, the best operational consulting also recognizes that it requires the combined efforts of consultants and clients. This is not just because each party brings different, but equally important, skills and expertise. Clients have to learn how to solve operations problems themselves, if they are going to be able to raise their overall performance.

BT managed to build a successful new consumer business that exploits its core assets while simultaneously solving a problem previously relegated to the wildest frontiers of the Internet - online micropayments.

BT Retail provides fixed line telephone services to more than 18 million homes in the UK. Since deregulation BT has performed well, maintaining an impressive market share of 73 per cent. However, in the midst of a static or declining market, BT had to find new revenue opportunities and plug a projected revenue gap of £1.5 billion by April 2006. Through a process of creative, entrepreneurial business development, BT discovered a business opportunity that would yoke together two compelling forces, and attach them to one of BT's most powerful engines, its billing capabilities.

The first of these market forces was the growing significance of online spending in the UK. The progress of consumer e-commerce is no longer reported on front pages, perhaps because there are fewer high-profile failures to be covered. However, the figures speak for themselves. According to Interactive Media in Retail Group (IMRG), which monitors the development of the UK's online markets:

The online shopping market was 72 per cent bigger in 2003 than in 2002 and has grown more than 16-fold during the 45 months in which the IMRG Index has collected market data. In the first month, April 2000, the e-retail market is estimated to have been worth just £80 million. Since then, an estimated £21.8 billion has been spent online by UK shoppers.

Focusing on the key Christmas shopping period, IMRG adds: ‘Online sales for November and December 2003 combined were worth a cool £2.5 billion, representing some 7 per cent of all UK retail sales.' (Source: IMRG, A cracking £2.5 billion e-Christmas, 19 January 2004). These figures speak eloquently of the steady growth of online shopping, showing how e-commerce is becoming an established retail channel.

The second force that BT wanted to harness was the emerging market in the kind of premium online information that people would be prepared to pay for. Pundits have long predicted huge global consumer markets in pure information, whether it be written, pictorial, video or music. These markets have been slower to take off than mainstream e-commerce offers such as online grocery shopping. However, recent successes in paid-for content, especially Apple's iTunes music download service, suggest that the big time may be around the corner. BT's own market research showed that people wanted quality content on the Internet and that 46 per cent of UK Internet users were prepared to pay for it. These findings matched experiences in Germany and the United States where high demand for quality, paid-for online content was already established. BT wanted to position itself as a leading carrier of transactions for such digital goods.

Tapping these growing markets would require a new solution: micropayments. The ability to make relatively small payments via a simple electronic means had already been pursued by many Internet industry players, but with little success. For many analysts, micro-payments fell into the frustrating business category doomed to be labelled as ‘a good idea'.

BT has confounded the conventional wisdom with click&buy, the micropayments scheme it launched in September 2002. By February 2004, there were 110 content sites in the scheme including Hello! Magazine, The Independent, Multimap, Channel 4 and Encyclopaedia Brittanica.

The click&buy concept, and its transition from idea to operational business, was developed by BT with its consulting partner, Edengene, beginning in the autumn of 2001.

Producing ideas

The first phase was idea generation. A small team of six BT people and five Edengene people was formed. The BT contingent brought the essential understanding of BT's business and deep knowledge of current trends in the market. The Edengene side included entrepreneurial talent and consultancy experience plus technological and financial expertise.

The joint BT/Edengene team set to work looking for market opportunities in and around BT's core business, studying market trends to identify emerging opportunities. Long-cherished beliefs and assumptions were challenged in order to reveal areas for renewed analysis.

The team also assessed BT's key assets and how these might contribute to a new business stream. One of these assets was its trusted brand. Another was its efficient, itemized billing process, which produces regular detailed bills for more than 18 million customers.

In four weeks the team generated more than 200 ideas. Nine of the ideas went forward to be worked up into full business propositions, complete with work on sizing the respective markets and studying the competition. Of this collection of nine, four were selected for implementation, including the proposition for online micropayments. The remaining ideas were not wasted: in the intervening period, a total of 21 ideas from the original 200 have since been developed into business streams.

Edengene's Tim Thorne recalls that the idea that became click&buy emerged when two other ideas collapsed together: ‘We had an idea for getting involved with micropayments along the lines of paying for vending machine items with your telephone number. The other idea was to set up a huge library of online content. Neither of these ideas made commercial sense.'

Paying for content

Following the deflation of the dotcom bubble and a widespread reduction in investment on online ventures by established businesses as well as start-ups, business developers have been struggling to find ways to make money from online services. The days when a snappilytitled Web site with a sketchy but compelling business plan could command attention and funding based on its potential future revenues have gone for good. With the hype largely removed from the sector, decision-makers focused on creating traditional business plans based on proven customer needs and revenue streams.

Until the decline in the dotcom market, online advertising had reigned as the supposed revenue engine of the Internet. However, the effectiveness and value of online advertising now attracted greater questioning. Advertisers withdrew their support for indiscriminate banner advertising. Those who remained in the online channel switched their spending to ‘pay per click' advertising spots, where the advertiser paid only when users clicked through the banner to a linked page. Soon the number of companies willing to run pay-per-click campaigns also shrank as companies began to run simple commission schemes based on actual purchases. While advertising survives on the Web, particularly in the form of paid-for advertisements on the leading search engine Google, content providers have largely given up on this method of funding their activities.

With the online advertising model generally discredited, many content providers turned reluctantly to subscription strategies. Since most of the best-known content providers on the Web are associated with print titles, it was logical that the failure of advertising would send them to the other source of revenues traditional in the print world. Leading sites such as that of the New York Times shifted quickly to subscription services, using the strength of their brands in the print world to assert the intrinsic value of their online content. After all, if a customer would pay for the New York Times from a news vendor, why should they expect to get the same content free online? The costs of producing the product did not dwindle to nothing just because the paper stage had been removed.

However, consumers have the same kind of resistance to online subscriptions as they do to offline ones. Despite the overall savings usually offered by subscription packages, many consumers are put off by the high up-front costs of a subscription and the long-term relationship it implies. While businesses understandably pursue customer relationships and are investing increasingly in maintaining them, too many companies forget that many customers are not looking to make commitments. In the realm of digital content, impulse buying is a particularly strong factor. We have been trained to buy print media, music and films as impulse items, strongly influenced by word-of-mouth recommendation and point-of-sale display techniques. These behaviours translate poorly to the online subscription model. The record companies have been among the first to learn of customer resistance to relationships of this kind. Services set up to offer paid-for access to the music of one or other record label have foundered on the simple truth that music buyers do not buy record labels: they buy music. And as the consumer population continues to migrate online, users increasingly want to be able to transact in the way they do in the real world. They want the convenience of simple billing, the anonymity of cash, the spontaneity of shopping. BT's research showed that over 80 per cent of consumers preferred ‘pay as you use' to annual subscriptions.

Subscriptions and pre-pay accounts, such as PayPal, work well for certain groups of customers but do not scale well to the mainstream. While regular New York Times readers may be happy to recognize themselves as such and enter into a subscription relationship, and loyal eBay traders are attached to PayPal as a way of transacting within the online auction community, less motivated consumers need a less committed channel to online payments. The simplest payment option for such users is the credit card, which is by far the preferred mechanism of Internet users. However, credit card transactions are not viable for small amounts. The handling fees charged by credit card companies make this mechanism unusable for amounts of under £5 or so. For the dollar-per-download model of most content providers, credit card is clearly an inoperable route. Even where the price of a piece of content makes the credit card mechanism a credible option, customers are reluctant to enter their credit card details repeatedly, and are especially suspicious of vendors they do not know well.

The concept of micropayments plays strongly to both consumer preferences for payment and the commercial realities of the credit card system. Micropayments offer a single, simple, secure system covering a range of approved content providers. Payment is made as simple as possible for the user, so that there is little practical or perceptual barrier to making the transaction. Micropayments add convenience and confidence to the e-commerce world, and grow that world to encompass a broader mass of consumers.

Hidden strengths

Various micropayment schemes had been launched for the Internet, often to loud flourishes that were not repeated at their eventual windings-up. The schemes ranged from quirky, entrepreneurial Web-based currencies like Beenz and Flooz to Compaq's heavyweight Millicent project, via bank-supported digital money schemes such as Mondex. These schemes failed for a number of reasons. In the first place, they suffered from inductive failure: a user would be asked for a special currency to pay for something, but only users who already had the special currency would be able to buy the item. Which would come first, the chicken or the egg? Few users were willing to transfer real-world money into invisible online money, especially if they could not see any vendors in their areas of interest who were prepared to take the novel currency. Where users confronted the digital money barrier from the merchant side, rather than interrupting the purchase process to sign up for the new payment mechanism, most preferred to find an alternative supplier.

The second reason that the majority of first-generation micropayment schemes failed is to be found in their supporting brands. Consumers simply do not look to technology companies like Compaq to act as a mint. Although Compaq's Millicent scheme involved the production of secure, digital tokens that could be used to store value, users were unwilling to make the mental leap between physical and logical currencies and to grant a technology company the right to create such tokens. Paper money had to be forced on to suspicious coin-users by law. It is unlikely that consumers will accept the further dematerialization of money just because its technical feasibility can be demonstrated.

Consumers have also proved to be less keen on the idea of traditional banks handling their online payments than we might have expected. Although retail banks have very detailed information on their customers and therefore try to develop business around customer relationships, customers stubbornly refuse to feel quite so warmly about their banks. Any bank's primary means of communication with a customer is the statement, which is (for most of us) a regular and depressing list of outflows and possibly debts and charges. The bank's utility to a consumer might be best represented in its ATM network, a facility consumers use largely on impulse. Thorne says: ‘We asked the question: If someone launched a micropayments system, who should it be? And people said that their first choice would be a credit card company. But their second choice was their telephone bill.'

BT has two particular assets that make it a natural provider of micro-payments. BT is regularly voted one of Britain's most trusted consumer brands. The BT endorsement would give content providers the ballast of security and trust they needed to attract online customers. BT's size, reach and longevity tells customers that the products and services it provides are reliable, scalable and good value.

The other key asset identified by the team was the telephone bill, known within BT as the ‘blue bill'. BT is the UK's largest biller. Every quarter, millions of homes receive accurate, detailed, timely bills that show even the smallest transactions. Line by line, the blue bill itemizes every transaction on an account, right down to penny charges. Billing is the lifeblood of any telecoms company, and often an area of technical challenge: many telecoms companies run scores of separate billing platforms, with complex bridges between them. The idea that the blue bill could be a route to new revenue, especially revenue derived from online activity, was a revolutionary one. Edengene's Thorne says: ‘The blue bill is a micropayments system. There are 2p and 3p transactions on there. And people believe what the bill says. They trust it.'

Creating the new business

BT gave the click&buy project the green light in January 2002. The team was asked to come up with a fully worked-out business plan. Within six weeks the team had built the business case, researching the market further, refining the proposition, developing an implementation plan and detailing a robust financial model.

The team also had to consider technology during this phase. The micropayments scheme would need a robust and secure system, otherwise it would fall prey to some of the failures that had destroyed previous micropayments initiatives and rebound adversely on the wider BT business. Building a system from scratch would have been possible, but BT wanted to launch the scheme as quickly as possible. The team did not want the project to disappear into a ‘big systems' development programme - an especial danger given the scheme's relationship with the business's core billing systems. The team decided to look elsewhere for a solution, and particularly in the German market, where the micropayments concept had had most success to date.

The German consumer market differs from those of the UK and United States in having very low credit card ownership. Micropayments had flourished in this environment, capturing the majority of online transactions in Germany from the nearest rival solution: cash on delivery.

Edengene explored and rapidly rejected a technology known as ‘drop dialling'. Thorne explains:

Drop dialling is a technique that's been used in the porn industry. The user is flipped over on to a premium-rate line for a few seconds and that's how the content provider collects. We had two major factors in our minds: great convenience, and a good customer experience. We found drop dialling just wasn't reliable enough. We watched a demonstration from the leading German player - and it failed. In any case, BT wants to encourage broadband access, which is an always-on connection, so switching the line doesn't apply.

The convenience factor applied as much to potential suppliers as customers, according to Thorne: ‘We needed to keep costs down for merchants to cooperate with our scheme. It's very expensive [for merchants] to implement e-wallets, for example. Their budgets for e-commerce have gone down in recent years.'

The team quickly found Germany's Firstgate Communications. The Firstgate micropayments solution had attracted some 400,000 customers in less than two years. Firstgate now has more than 1.4 million customers. The Firstgate system worked well, was scaling well, and was provably secure, standing up to a BT security audit.

Firstgate did not have the resources to bring their micropayments model to the UK but were happy to license the technology to BT in a deal brokered by Edengene.

The technology works by exploiting the simplest element of the Web: hyperlinks. A merchant can charge for any item simply by allowing users to click on a special link that takes them to a charging page. Merchants have a great deal of flexibility in how they use the system, and can amend prices whenever they want. For example, a content provider can specify that a story is available for £1 on its date of publication, but 50p thereafter. Users sign up for the click&buy service by getting a simple username and password combination the first time they use a merchant in the scheme. They can then choose their preferred method of regular settlement: direct debit, credit card, or telephone bill.

With the technology in place, the project began to accelerate towards launch. The management team was appointed, including an interim CTO, Strategy Director and Business Development Director from Edengene. Despite the organizational support of BT and its brand, the team was effectively setting up a small standalone start-up business. The team therefore designed the business as an entrepreneurial unit, and included an incentive scheme for staff.

The team also committed to making its first sales before the formal launch of the business. While the technological implementation went ahead, the team worked to find 40 initial content providers. The challenge here was to overcome scepticism in the vendor marketplace and demonstrate how micropayments could deliver more customers for online content. Case studies were built, demonstrating the potential and putting the case for moving quickly.

The trial of BT click&buy went live in July 2002 with 20 content providers, delivering its first revenues just 10 months after the initial brief to Edengene. The full public service with 40 content providers was launched in September 2002. Payment by credit card, debit card or direct debit were the initial options offered. The option to pay via the ‘blue bill' - a core element of the proposition - was challenged by competitors but the industry regulator ruled in favour of BT. Click&buy became an option on BT telephone bills, first to selected customers in March 2003 and then, by the summer of 2003, to all 18 million BT domestic accounts. Currently around one third of click&buy users use the telephone bill option.

Today BT click&buy is the UK's leading micropayments service, allowing all BT home customers to pay for quality online content through the telephone bill. In July 2003, BT click&buy launched a new ‘roaming' initiative, giving the online payment solution access to an additional 1.4 million click&buy account holders in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Spain, Holland and the United States. Recent enhancements to the service include the launch of click&vote, which allows users to register TV poll votes online, and click&give, an easy way for users to make donations to charity. Mobile payments have been added to the scheme as well, enlarging the scope of the service still further.

Prior to the launch of click&buy, BT was not seen as a leader in the UK's online industry. In fact, it was often seen as a brake on progress, especially with its national broadband roll-out. Click&buy plays to BT's key strengths as an enabler of valued services to the mass market. The business stream fits well with its core competences of infrastructure development and trustworthy communications.

Click&buy also releases exceptional value from one of the most important business relationships in the modern world: the itemized telephone bill. With the familiar ‘blue bill' now evolving to encompass every kind of digitally ordered or delivered service, BT is well placed to carry the bulk of transactions in this steadily growing channel. This project has proved that with the combination of imagination and robust business thinking, it is possible to create ventures in and adjacent to a company's core business that will both leverage existing assets and meet customer needs, now and into the future.

Edengene's Tim Thorne is adamant that click&buy makes a major contribution to BT's market positioning: ‘This is what BT should be doing: acting as an enabler. This is a very strategic move for them. First, it encourages people to put content up for charging. Second, as broadband evolves, this gives them a wide platform for [charging for] different content.'

Thorne describes his firm's service as ‘outsourced business development for business ventures'. In practical terms, this service delivers unusual insights that can then be converted into functioning business processes. Those on the inside of an organization can easily become estranged from the business's own assets, and even fear them. Certain practices or products can become untouchable, as a sense builds that they are too difficult, mysterious or fragile to tamper with. The ‘if it ain't broke, don't fix it' attitude can further encourage people to avoid reassessing, and reapplying, their core competences. External entrepreneurs such as Edengene's consultants do not share the same taboos and have nothing to gain by subscribing to any erroneous beliefs they encounter when working with their clients. They think the unthinkable, in order to do the undoable.

Using this kind of external consultancy is also one of the few safe ways that an established organization can import an entrepreneurial spirit into its own community. It is hard to create an authentic ‘start-up' experience within a large organization, although many have tried with so-called ‘incubator' divisions where pet projects are given some shelter from the typical reporting requirements and team members may be offered a share in resulting profits. However, these in-house initiatives often suffer from a sense of unreality. The parent organization is always there to catch the fledgling business if it fails. No one's home is on the line. By exposing staff to consultants such as Edengene's, an organization of the massive size of BT can exploit the urgency, verve and nerve of a group of entrepreneurs without taking on any significant risk. Staff are shown a different way of thinking and working, and thereby shown that perhaps the obstacles they assume exist in their day-to-day environment may not be so permanent after all. This kind of intervention not only creates new businesses in short order, but also sparks a new sense of vision in the staff who are involved.

A community hospital used a theory associated with the manufacturing sector to confound cherished assumptions about wringing greater value from constrained resources. Patient treatments are soaring, but neither the hospital nor its staff or its funding have been enlarged.

Managers in all types of businesses often find themselves confronted with zero-sum situations. Their experience and intuition tell them a win-win solution is the optimum exit point for any challenge to the business, be it big or small. But sometimes the constraints leave so little room for flexibility that even the most creative manager is forced reluctantly to conclude that ‘something's got to give'.

Tony Hadley, Head of Community Services at the Norwich Community Hospital (NCH), faced such a dilemma in the summer of 2002. He needed to increase the number of patients that NCH could treat, in order to improve patient care and to relieve pressure on beds in the acute hospital. However, no additional budget was available and it was hard to imagine his hard-pressed team could work any harder.

Various change initiatives had already failed. Yet, working with Ashridge Consulting, NCH increased the number of patients it treated by 40 per cent within three months, with no changes to its existing resource levels. Together NCH and Ashridge worked some latter-day alchemy: they measurably made something out of nothing. The transformation in the hospital's operational performance is living proof that ‘more money' is not the answer to the health service's problems. There is a smarter way.

Creating something from nothing

Achieving change in the National Health Service is a constant challenge. The government's high profile 10-year NHS Plan embraces a full agenda of change initiatives. Targets have been introduced throughout the service, driving a shift to a culture that values performance and accountability alongside clinical excellence. Throughout its history the NHS has tried to match the growing expectations of its users as medical advances have widened the range of treatments it can offer. Government, media and NHS staff have been unanimous in their belief that the service can only meet ever-growing needs by securing infinite resources.

From one perspective, they are of course right. Take any individual part of the system, and one can make a case for meeting targets through the application of further resources. Manpower and capital can solve problems in isolation. The difficulty arises for managers who have to decide where to allocate resources in order to benefit patients across the whole health system. Given the mass of competing demands, any individual allocation decision will appear to deny other areas. If there is one belief to match the idea that a bottomless well of resources will cure all the NHS's ills, it is the belief that existing methods make too many areas of healthcare into a lottery.

Ashridge's Gary Luck says: ‘From our experience, current practice within the NHS is to allocate resources as evenly and as fairly as possible across the organization. Unfortunately, this practice of spreading resources fairly and evenly can prove damaging to the quality of patient care and doesn't enable the NHS to treat more patients.' Ashridge therefore took a different view. The consultants agreed a three-part primary objective with NCH. The team would use a combination of techniques to increase the number of patients going through the NCH and increase the quality of patient care without increasing resources or making staff work harder.

They also set a secondary objective of capability transfer, an objective Ashridge adds to all its health service projects. Ashridge would transfer learning and skills so that NCH could build its own internal consulting capability. The transfer process would run throughout the project, rather than being added at the end of the process as an afterthought. NCH would emerge as an organization ready and able to identify and address its own problems, long after the initial consulting intervention was completed.

Applying the theory of constraints

The theory of constraints is a model created by Eli Goldratt and successfully applied in organizations around the world. Initially used in manufacturing, this model is now being used to great benefit in other environments, including the NHS.

Goldratt's key insight was that organizations tend to be structured, measured and managed in parts, rather than as a whole. While breaking large problems down into smaller parts is a rational method for dealing with complexity, the result is often an overall reduction in performance standards and a seemingly endless list of chronic inefficiencies and conflicts.

The barriers erected within organizations are usually apparent to their people. Few staff are happy to work in ‘them and us' cultures, but they feel powerless to challenge the organizational boundaries. Short-term targets focus minds on immediate actions, and leave little time for planning the future. At the same time, proposing change exposes the organization to new risks. Achieving a healthy, integrated business demands the removal of those barriers to success, but the day-to-day reality of running the business seems to preclude improving the business.

Goldratt's theory of constraints enables organizations to apply change in a way that creates long-term, systemic benefits. The process is described in terms of three questions:

-

What to change?

-

What to change to?

-

How to cause the change?

In the first step - What to change? - analysis of cause and effect is used to trace the relationships between observable symptoms and underlying problems. The method looks for ‘core conflicts': central unresolved dilemmas around which the organization is frozen or trapped. Core conflicts are often surrounded by palliative measures such as policies and measurement processes designed to deal with symptoms rather than the underlying problem.

The second step - What to change to? - challenges the assumptions sustaining the organization's newly revealed core conflicts. Solutions can now be developed and evaluated to replace the conflicted area. Such solutions are tested to ensure that they do not create undesirable side effects of their own.

The final step - How to cause the change? - involves building a transition plan to ensure that the designed changes take place, and take root, in the host organization.

Ashridge applied the theory of constraints using an application known as ‘drum-buffer-rope' which recognizes that a system can only run as fast as the speed of the weakest link. This is ‘the beat of the drum', the pacesetter of the organization's overall activity. The ‘buffer' safeguards the bottleneck, ensuring the most constrained link in the system is always active to its full capacity. ‘Drum-buffer-rope' has been widely applied to manufacturing processes. In these settings, material is released according to the pace set by the drum. The relationship between the ‘drum' and ‘buffer' is controlled by an operation known as ‘rope'.

At a two-day workshop, 25 staff were introduced to the theory of constraints via these two tools. A dice game using dice and tokens representing patients was used to demonstrate the effects of uncertainty and variation on dependent events and whole-system behaviour within the hospital.

The joint team agreed that modelling system behaviour would only have a real-world impact if they could create a fertile environment for change. Soft skills would be needed to allow the organization to learn its way into new processes and behaviours. The team therefore developed a project plan to roll out changes while securing buy-in from all staff. Support of innovation and the challenging of existing working practices and boundaries would be key to effective and permanent change.

Boundary effects

The team's analysis of cause and effect showed that the overriding constraint on NCH's performance was a chronic bottleneck at the point of patient departure. Patients could not be released from the hospital at the earliest appropriate moment. Resources were essentially being tied up with inactive cases, blocking new cases from entering the start of the care chain.

A conflict that occurs at the edge of an organization can be one of the hardest to tackle and resolve. In this case, the slowdown at patient release was not entirely within the control of NCH. Other agencies had a major part to play, notably Social Services.

In order for a patient to be discharged safely, a number of events need to be synchronized. These include, for example, availability of prescriptions, transport, home improvements, support packages and accommodation for continuing care if appropriate. The complex nature of care packages provided by Social Services was the most frequent cause of delayed patient discharge.

Solving this boundary issue required the team to enlarge their understanding of the hospital system to include colleagues in Social Services. This non-traditional view of the hospital's scope rapidly emerges from a patient-centred analysis of NCH's processes, but is hidden by the structure of the organization and its partners. Following patient experiences in terms of events and outcomes rather than their sequential ownership by care agencies is a growing theme in the modernization of the NHS, and is elsewhere helping to refocus resources in general practice and public healthcare information services.

NCH/Ashridge team therefore included members from the relevant Social Services teams in the pursuit of potential solutions. Working together, the combined team managed to isolate and resolve what seemed at first to be a rigid, insurmountable obstacle. The obstacle was disguised in terms of the protection of patient confidentiality - a vital human right, and one that was inadvertently working against the best interests of the patient. The barrier was surrounded by laws and codes of practice. In other words, the team had found a classic core conflict.

Data protection laws prevent Social Services staff access to patient information until the patient has been discharged from hospital. The legal brake on information handover contributed greatly to NCH's terminal bottleneck. If colleagues in Social Services could begin planning patients' aftercare before they were discharged, there need be no inherent delay at this point in the chain of care. Ideally, social workers needed to be planning patient aftercare before the patient was admitted to the hospital.

The team found an imaginative workaround that immediately made sense and could be supported by all parties. A member of NCH staff would begin the patient's discharge plan and manage it until the point when it was legally correct to hand it over to Social Services. It is a simple solution, but one that only became visible and doable in an open and trusting environment. The team generated an elegant and lasting solution to a major problem by working with each other, with respect for the appropriate laws, and with committed concern for the patient's best interests.

Team-think revisited

The core team had to be capable of transferring skills and knowledge throughout the hospital and other associated agencies such as Social Services. This involved a programme of support and just-in-time skills training and development as the theory of constraints change programme unfolded.

The team was trained to deliver the key messages of the dice game and to facilitate workshops for stimulating new thoughts to address old problems. The majority of the workforce, from porters to medical consultants and totalling some 180 individuals, were introduced to theory of constraints thinking through a series of two-hour lunchtime sessions. This transfer of knowledge replicated the principles inherent in Ashridge's training of the core team, which included:

Figure 5.1: Dependent events with time buffer

-

avoiding jargon where possible;

-

allowing staff the space to develop their own solutions;

-

giving staff the opportunity to think about the significance for them as individuals, for their department, the hospital as a whole, and - crucially - for the patients;

-

providing the opportunity to say ‘No' as well as ‘Yes'.

Gary Luck says that guiding the team's thinking habits and attitudes is crucial to avoiding the traps inherent in any organization susceptible to a blame culture:

We treated [the project] as an enquiry into what we might be able to do. Each time we met we offered different thoughts and explored together whether they'd be helpful. It's an exploratory way of finding benefits. I often started workshops by reminding people they could also say ‘No'. That way you can build a true consensus.

The size and disciplinary diversity of the organization could easily have blocked the change initiative. The workforce embraces a range of responsibilities and viewpoints spanning porters' to consultants'. Various departments and organizations such as community hospital, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and Social Services have their own management targets and professional issues to guard.

Potential problems in executing the changes were pre-empted by the transfer of facilitation and consulting skills to the core NCH team. Staff from cross-functional and multi-disciplinary areas were involved to co-create and implement the content and process.

Genuine new thinking was stimulated by creating an environment in which staff felt they could be open and honest about views and feelings. Meetings held in the era before the project have since been described by participants as being like rehearsals for a play. Actors spoke the lines they had laboured to learn and voiced the entrenched views of their sectional interest. Trapped in the evolved habits of their culture, they lacked a simple analytical model that might help them find ways forward in situations of uncertainty and complexity. This project helped them understand that whereas linear styles of leadership are relevant in situations of low uncertainty and high agreement, a more facilitative approach is required in situations of high uncertainty and low agreement as so often found in today's - and tomorrow's - NHS.

Better patients, better staff

The project's results were immediate and outstanding for patients, the hospital and staff alike. After 20 days' consulting input, immediate breakthroughs in performance were achieved without extra funds and without staff having to work harder. The average length of patient stay was reduced from 35 days to 20 days, enabling a 40 per cent increase in the number of patients going through the hospital. This step change was achieved within a few months from the start of the project in August 2002, with continuing month-on-month improvements. By March 2003 the average length of stay had fallen further, to 19 days.

Based on the measured increases in throughput, the team calculates that an additional 700 patients can be treated each year. Funding the treatment of 700 extra patients through traditional routes would have cost the hospital around £2 million.

Readmission rates of patients discharged from the hospital are also declining. This finding indicates there has been no reduction in the quality of patient care.

On the organizational side, the core change team has become a group of very able internal consultants. The team members' newly acquired learning and techniques have changed NCH into a learning organization, able to identify and address its own problems on an ongoing basis. Staff were given the time, leadership and support to develop their own solutions. They were also given the opportunity to think about the significance of change for themselves as individuals, for their department, for the hospital as a whole and - crucially - for the patient. This way of thinking has now become orthodox throughout the organization.

Several months after the dramatic improvement in results, staff are constantly overcoming new problems. They are also beginning to look at other areas within the Health and Social Care system with which they are linked, including general practice and care homes. They are sharing their learning, and helping to create environments for new learning in the organizations with which they share the responsibilities of care.

Problems with recruitment and retention have receded at NCH, described recently as ‘the place to work' for medical staff in the area. An occupational therapist says: ‘I have turned down other jobs because I don't want to move away from a theory of constraints environment.'

Confidence among the staff has also soared. A Social Services employee says: ‘Before, if I had a problem I would want to blame someone and walk away from it. Now it's just an issue that I know I can tackle.'

Meanwhile Chris Price, CEO of NCH says: ‘TOC has captured the imagination of staff at NCH. It has got everyone pulling in the same direction and has been a great tool for team building as well as service redesign.'

This project proves that a combination of rational, analytical tools and a supportive, open communications environment can dissolve zero-sum situations and radically alter the performance and capability of an organization. NCH and Ashridge have shown it is possible not only to make existing resources go further without loss of quality, but also to foster a culture eager to seek and implement further changes.

NCH's experience also implies that extra resources, applied blindly, can easily be consumed in buttressing broken structures and bypassing broken processes. Decision-makers owe their stakeholders the duty of questioning the band-aid solutions holding their operations together, even if - especially if - they mask the most politically sensitive and culturally loaded aspects of the business.

The theory of constraints and the adaptations made to it by Ashridge formed an entirely novel approach to management within the NHS, demonstrating how academic models can be put to practical use in the business environment via experienced consultants. It is unlikely that such a technique would be discovered at random by a manager within an organization like the NHS, or that such a lucky discovery would attract the support needed to apply it successfully to any area of the business. This is an important role for the consulting industry: good consultants act as conduits for the effective dissemination of valuable techniques that would otherwise not exact their maximum benefit.

NCH is an organization that has literally been refreshed by its use of the theory of constraints and the associated tools and techniques Ashridge introduced. As core conflicts are brought to the surface and eliminated through collaborative enquiry by motivated staff, a new health begins to spread through the organization, strengthening its ability to act and changing the lives of the customers it touches. Gary Luck says: ‘While the actions we took here may be specific to this organization, the principles of what we've done are relevant to others. Real change isn't like a cog that you can move from one machine to another. Businesses are living entities that need developing from the inside.'

Designing and managing Europe's most complex IT relocation created the opportunity to redesign the way GCHQ works, refitting it for the new challenges of the 21st century.

The genteel spa town of Cheltenham has been the discreet home of the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) since it moved there in 1952. Long referred to vaguely as a department of the Foreign Office, GCHQ functioned outside the public consciousness until 1983 when the organization's role was formally explained to Parliament. GCHQ reports to the Foreign Secretary and works closely with MI5, MI6, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and law enforcement authorities.

GCHQ is responsible for two functions: signals intelligence and information assurance. Signals intelligence is the lawful interception of electronic emissions to protect the vital interests of the nation and to support military operations. Information assurance defends government communication and information systems from eavesdroppers, hackers and other threats, and protects the UK national critical infrastructure (such as power, water and communications systems) from interference. Both of these functions operate around the clock, and GCHQ is supported by one of the most advanced IT facilities in the world. The UK's national security depends on GCHQ's operational integrity and continuous availability.

The ending of the Cold War gave rise to a new role for the intelligence and security agencies. The 1994 Intelligence Services Act (ISA) identified national security, economic well-being and the prevention and detection of serious crime as the main threats to our security.

The organization responded to the challenges, introducing new ways of working, with the key areas of focus being on better team working. However, it has been extremely difficult to achieve this transformation in working style, because the organization occupies more than 50 buildings spread across two sites some four miles apart. Many of the buildings date from World War II and they are served by a vast array of different computer systems.

In 2003 GCHQ began the process of moving its 4,500 staff from its existing sites at Oakley and Benhall to a purpose-designed facility in the western part of Cheltenham. The building cost £337 million, and it forms part of the largest private finance initiative (PFI) project yet undertaken in the UK. The total cost of the PFI project is around £1.2 billion, including a 30-year service contract covering the provision of ancillary services such as security, logistics, telephony and maintenance. An additional £303 million covers the cost of technical transition, the move and the installation of the IT infrastructure to the new site.

The new building, known as the Doughnut, was completed in June 2003. Business units began moving in during September 2003 and by March 2004 some 2,200 staff had been relocated. The move was scheduled for completion in the summer of 2004. Part of one existing site will be kept operational for several years in order to ensure operational continuity.

The Albert Hall would fit comfortably inside the space at the heart of this immense building. The Doughnut contains over 5,000 miles of communications cabling, a length that would stretch from Cheltenham to Cairo and back again, and 1,850 miles of fibre optics. The fully equipped computer rooms cover an area equivalent to three football pitches.

New methods in intelligence work

A move of this size is complex enough, but GCHQ saw the New Accommodation Programme (NAP) as more than a logistical exercise. GCHQ used the move as an opportunity to enhance considerably its new ways of working to become a more joined-up and flexible organization. It needed to alter both its business behaviour and develop new systems while integrating with existing legacy systems to ensure business continuity.

A GCHQ spokesman, speaking at the start of the relocation project in September 2003, said:

A lot of our business improvements rely on good teamwork, and the design of the Doughnut will make it a lot easier for our mathematicians, linguists, technologists and intelligence analysts to share information either face-to-face or through a common computer system. Additionally, when we face new threats, the open plan design is flexible enough to allow us to set up new teams in the space of a few hours - people will not be tied to specific desks any more.

The workforce at GCHQ is unusual. The organization employs more mathematicians than the average university mathematics faculty, and its linguists are fluent in 67 languages. A range of specialisms peculiar to intelligence work makes for a multi-disciplinary environment in which events are being tracked and interpreted from a range of viewpoints in real time. The complexity of modern threats and the globalization of terrorism are both publicly quoted reasons why modern intelligence work requires a greater degree of collaboration than it did in the relatively ordered world of the Cold War. GCHQ staff attempt to find meaningful patterns from a mass of data of different types, and there are few fixed assumptions they can apply in their work. Sharing information and ideas across disciplines is therefore a key tool in their method.

The obvious answer to the challenge of sharing information is the provision of excellent information systems. But, appropriately enough for the intelligence activity, the obvious answer is in this case misleading. According to David Stupples, formerly of PA Consulting Group and now at City University in London, human communication is the key:

In the old buildings [staff] were physically compartmentalized in different rooms, and even in rooms within rooms. They need a more global picture today, and it helps when people can talk to each other. They need more openness within their world, to share views and ideas. Today's terrorism is in a global context, so [GCHQ staff] being part of a wider collaborative community is good for the country.

Merely swapping or copying more information between individuals would not have helped to produce that collaborative community. ‘The information flowing around these people is already dense,' says Stupples. ‘Passing more of it around wouldn't help.' By ‘dense' information, Stupples means highly complex and apparently unstructured information that needs to be analysed into meaningful components before it can be understood, or related to other information. Different experts need to ‘unpack' the information and discuss it with each other. Since all information is potentially related to everything else, it is not possible to predict who needs to see what at any given time.

The situation at GCHQ is the opposite of that which pertains in a highly structured expert environment, such as a hospital. A hospital's casualty department can screen incoming patients using ‘triage', a French word meaning ‘sorting'. Triage nurses determine who needs to be seen most urgently by doctors, based on a preliminary examination of each patient. Patients are then processed through the hospital via a series of diagnostic sessions and tests, each aimed at excluding certain possibilities, and eventually a course of treatment is decided upon.

GCHQ, on the other hand, is a perfect example of a highly unstructured expert environment. The typical escalation process used at a hospital would fail to identify and prioritize threats at GCHQ, because the behaviour being examined by the organization is designed precisely to thwart detection and categorization. GCHQ must be organized to ‘expect the unexpected' but nevertheless determine what is important among the multiple streams of data coming in.

A moving experience

The primary objectives for the New Accommodation Programme (NAP) were to complete the move to the new headquarters within a self-imposed, aggressive schedule while maintaining continuous operations throughout, and to deliver significant business and cultural improvements. To achieve these objectives, four major issues needed to be addressed.

The first issue was the assured continuity of GCHQ's service. The programme could not stop the running of GCHQ, even for a single moment. A programme of this size and complexity would normally require downtime for systems' installation and testing, but GCHQ's importance to national security ruled out any loss of service.

The second issue was the complexity of GCHQ's computing facilities. The organization had a large number of separate systems, each one larger than the IT facilities of most corporations. The organization had also developed many connections among the systems, creating a highly interdependent ‘system of systems' that was hard to understand and maintain. While the systems remained in place, they delivered excellent service. Contemplate moving them, and their fragility became apparent. At the purely technical level, GCHQ was also running what was estimated to be the largest supercomputer cluster outside the United States. This meant that professional expertise in relocating the systems was scarce.

Third, the project's milestones could not be altered. The nature of the contracts supporting GCHQ's move across town set the timeline in stone. The move had to be completed within aggressive time limits and delivered within an exacting cost and specification constraint.

The final issue compounded the impact of the first three and raised the stakes still further. Not only had the team to move these complex systems within a fixed timeline without any interruption to service, but it also had to improve the systems architecture in the process. A substantial number of legacy systems had to be fully integrated with each other, and redesigned to allow continuous improvement in the future. In the words of the project's Design Authority, this ‘was a bit like rebuilding an aircraft carrier from the keel up, whilst it is at sea and flying its aircraft operationally'.

Adapting a methodology

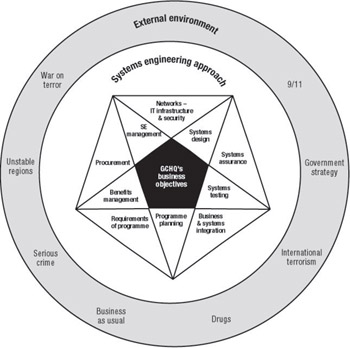

PA Consulting Group was appointed to help GCHQ with its move because of the consulting firm's leading expertise in systems engineering. ‘Systems engineering' may sound like a generic term, but it is in fact a specific professional discipline with a long history. The International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) defines systems engineering as: ‘an interdisciplinary approach and means to enable the realization of successful systems. It focuses on defining customer needs and required functionality early in the development cycle, documenting requirements, then proceeding with design synthesis and system validation.'

The key to systems engineering is its holistic approach. Each stage in the process is analysed in relation to the overall problem being attacked, using the seven dimensions of operations, performance, testing, manufacturing, cost and schedule, training and support, and disposal. Systems engineering has been traditionally used for building new things in a static situation, such as a nuclear submarine in a dry dock. It has also been used extensively in NASA's space programme, where mission objectives and timetables are fixed many years in advance.

There were two reasons why a traditional systems engineering approach would not work on NAP. First, GCHQ already existed, and so this was a case of a major role change for an existing operational facility, rather than building anew. Second, and equally as important, GCHQ needed to evolve continuously to align proactively to new threats. The earth and planets move in predictable cycles; but GCHQ's business is anything but predictable. PA therefore modified its systems engineering approach with GCHQ to create a methodology tailored to GCHQ's unique circumstances. The modified methodology took into account the volatile external environment in which the organization exists.

This special adaptation of the systems engineering approach made it possible for changes to be safely applied without impacting current operations. PA's skills and knowledge of systems engineering were combined with GCHQ's knowledge of its systems and goals to form a highly capable and integrated team, able to deal with the immense complexity involved in the delivery of a successful solution.

Figure 5.2: Systems engineering approach taken at GCHQ

Working through the move

Even the most sophisticated methodologies only succeed in practice if they are applied in a well-managed, flexible environment. The PA/GCHQ team planned the style of the relocation project to ensure success, paying careful attention to risk reduction, morale and direction.

First, the team designed a step-by-step approach to the relocation in order to minimize risk. Business continuity dictated that the systems, people and data could not be moved in one single bound. Instead, the team developed an incremental plan that involved the reengineering of the legacy systems, integrating these with new systems while addressing business issues, and finally moving the people. This means that a large proportion of the necessary technical redevelopment effort was carried out prior to the physical relocation, thereby breaking any critical dependency between systems and people.

Second, the team determined that meticulous planning, issue management and dynamic testing were all needed to make the complex relocation task achievable. For example, to assure business integrity during enhancements to existing IT applications, the team implemented ‘roll-back' systems. These ensured that if a change was applied to an existing service and it did not work as planned, then the service could quickly revert to its previous stable state, without any interruption to GCHQ's operations.

The third plank of the delivery approach was to use computer simulations. The team ran a range of different simulations to analyse the pros and cons of different ways of tackling the move. The simulations included trade-off analyses to show how different sets of tasks would impact on each other, allowing the team to define an optimal series of activities. Other simulations covered performance analysis and failure mode analysis, enabling the team to design a relocation plan that would minimize the likelihood of loss of service.

The team also performed scenario testing to help decide on how the business could be supported under all foreseeable circumstances. For example, simulation was used to develop a programme schedule that could accommodate massive parallel working. This parallel working was instrumental in meeting the aggressive time schedule.

The fourth aspect to the delivery approach was ‘the people element'. The team knew that moving people physically was only part of the challenge. Ensuring their commitment to the new systems environment, and their flexibility during the move, were key components of the project's overall success. The team developed a change management approach that would fully engage GCHQ staff and ensure that they exploited the changes in their IT systems. This change management strategy had three elements. The first element was operational pilots, with early versions of new systems exposed to staff so that they could begin to familiarize themselves with the coming changes. The second element was the involvement of users in systems design, testing and integration, so that staff had a sense of ownership of the systems being built. The third element was the transfer of learning from other organizations that had experienced the magnitude of large-scale change, which was achieved by liaising with other PA clients.

The final aspect of the delivery approach involved demonstrating the combined expertise of a multi-disciplinary team working in a collaborative style. The project called for strong technical leadership and insights from mission-critical industry sectors, such as air traffic control and rail transport. PA drew on the whole range of its capabilities, including IT skills, programme management, change management, modelling, systems integration and network design. To supply all these competences, PA assembled a team averaging 40 members and representing more than 600 years' experience with complex computing systems. This was the most experienced team that PA had ever fielded, and it was matched by a similarly experienced team from GCHQ. The two groups formed a joint team that exemplified, and encouraged in others, the collaborative style of working that GCHQ wanted to foster in the new headquarters.

Negotiating bumps along the road

Shipping GCHQ across Cheltenham was clearly not a simple matter of ordering a fleet of pantechnicons and a mountain of boxes. Unpicking the existing IT environment, designing a new target environment and calculating the transforming steps that would turn one into the other called on a range of intellectual skills. Designing the delivery approach called in a number of softer skills, such as issue management and system piloting. Despite these careful preparations, the team still had to deal with unexpected problems - not least the escalation of the organization's role after September 11. The relocation programme coincided with a period of major world conflict, but the systems engineering-driven scheduling approach provided the flexibility to accommodate these events, some at very short notice. The pattern of the relocation was successfully reconfigured on a number of occasions to allow changed priorities to go ahead.

GCHQ has always had to change its IT facilities and business processes as it adapts to changing world conditions. Given the global crises that occurred during this programme, changes were constantly occurring. Configuration management, or knowing the status of GCHQ's systems at all times, therefore became crucial. The specially tailored systems engineering approach meant that NAP could accommodate these changes relatively easily, thereby maintaining the integrity of the overall facility and the viability of the programme.

Even without these unprecedented challenges, GCHQ presents a tough environment for external agents of change. The organization's IT facilities and working practices have evolved over many years and interact in highly complex ways. There is an immense body of knowledge at GCHQ, and in order for the PA people to become effective quickly they had to tackle an extremely steep learning curve. Maintaining the team's level of expertise on a long-term assignment was also a challenge. Careful ‘succession planning' ensured that the PA contingent remained effective over the several years of this assignment, despite inevitable staffing changes. A training scheme quickly brought new team members up to speed.

Knowledge also flowed in the opposite direction, from consultancy to client. Prior to NAP, the government standards for projects and programme management (MSP and Prince 2) were not explicitly aligned with systems engineering. The GCHQ/PA team developed a successful alignment that has since been endorsed as the preferred method for future change programmes.

In its World War II guise as the Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, GCHQ created the world's first electronic computer. Called Colossus, the machine enabled the decryption of messages sent from the German high command, playing a vital role in the allied war effort. Today, the organization is using its experience of moving colossal systems to ensure that the increasingly complex technical environment continues to yield vital intelligence in the fight against global terrorism. By marrying the strength of information-processing systems with human teamwork, GCHQ is now developing a new collaborative culture to replace earlier compartmentalized styles of working.

Convincing experts that the way they solve problems can be captured and taught helped Sun Microsystems claw back more than 16,000 lost days for its customers every year.

Support: an innocuous sounding word implying a sturdy, reliable, and probably simple structure that props up an edifice. But in the business context, while ‘support' may designate a quality that users or customers take for granted, from the point of view of the support provider it can be a major headache - and a cause of critical business failure.

Excellent support is crucial to the IT business, and increasingly to other kinds of business as the goods and services on offer in our markets become ever more complex. While not all customers invoke support, for those who do so it rapidly becomes the defining feature of the customer experience. Getting support right, on a predictable and repeatable basis, directly influences service renewals and repeat product purchases.

The ‘always-on world'

Sun Microsystems is an established provider of hardware, software and services to the business market. By 2000, Sun's worldwide revenues of US $18 billion were being fuelled by sales to large organizations with heavy transaction volumes, such as banks and telecoms companies. These customers are ‘always-on' businesses, responding to customer needs in real time and often working on a global basis. When there is a problem that affects delivery to a customer, every second counts.

Sun was solving most customers' problems quickly and effectively. Many customer problems were rapidly and accurately resolved by generalists and specialists within a country organization. However, problems that escalated from Sun support organizations in individual countries to Sun's worldwide backline support were taking too long to fix.

The engineers in the backline support are the most experienced in Sun, and they see the toughest customer problems. Sun invests continually in their training, support software and processes. With the best people available at the point of pain, what else could Sun do to fix problems faster?

Sun managers found that the handover point between country teams and the backline was a key determinant of success in resolving customer problems. A traditional view of the support function might begin to analyse this situation in terms of structure, and look for ways to change the support team organization. After all, ‘support' sounds like a structural element. Sun, with the help of consultants Kepner-Tregoe, had a key insight that led them to take a different path. They realized that the transition between teams was a process embodying the transfer of information. If the team could improve the capture and presentation of critical information at this point, Sun could mobilize its existing resources to greater effect.

In simple terms, when the backline first heard of a customer problem from their colleagues in the country organizations, information was often missing or vague. Backline staff had to spend additional time gathering problem-specific details before they could progress. If Sun could improve the quality of this vital information, then they could fix their customers' problems faster.

Sun therefore launched the Sun Global Resolution SM (SGR) troubleshooting project in July 2000. The goal was dramatically to speed up resolution of customer problems by using rational troubleshooting processes. The new processes would be institutionalized within the customer support service chain: baked in to the way Sun dealt with all customer problems throughout its global operations.

Experts in action

‘Rational troubleshooting' may sound like a contradiction in terms. Our mental image of troubleshooters is of lone, taciturn and expensive individuals who are called in to work some kind of magic when mere mortals have failed. If leading managers are lauded for their ability to take ‘a helicopter view', troubleshooters are the daredevils dangling beneath the spinning rotors.

Consultants Kepner-Tregoe have a different take on troubleshooting. Founded in the 1950s, Kepner-Tregoe was built on the premise that people can be taught to think critically. The firm's founders had studied breakdowns in decision-making at the US Strategic Air Command while working for the Rand Corporation. They discovered that successful decision-making by Air Force officers had less to do with rank or career path than the logical process an officer used to gather, organize, and analyse information before taking action. Their work proved that applied expertise can be mapped, and taught. Shifting their studies into the civilian world, Kepner and Tregoe observed the practices of both effective and ineffective decision-makers responding to complex, repetitive challenges.

They developed their findings into the ‘rational process', which became the Kepner-Tregoe method for effective organization management. The firm also pioneered the ‘train-the-trainer' concept, an approach to skills transfer now widely implemented throughout the business world.

Kepner-Tregoe's cultural origins are similar to those of Sun. Both companies share a heritage of academic rigour and garage start-up pragmatism. Working together on Sun's support capability, the combined team was able to maximize the expert value of Sun's engineers to improve the customer experience radically.

Sun asked Steve White, a UK-based senior backline engineer trained to coach his colleagues in Kepner-Tregoe troubleshooting, to lead the SGR troubleshooting project. White says:

We already knew that Kepner-Tregoe's troubleshooting processes gave us what we needed to create the SGR troubleshooting project. But a project of this scale needs genuine partnership, not simply intellectual property. Right from the start we established a baseline of trust with Kepner-Tregoe's consultants. Kepner-Tregoe's processes gave us a common way of working together that meant that when issues arose, we could sort things out quickly.

Escalation ping-pong

Like almost all technical support organizations, Sun used a management escalation process to deal with problems raised by customers. Escalation allows organizations to tag problems for priority and severity depending on the age of the problem, and the degree of customer pain it is creating. The escalation process itself notifies an increasing number of senior managers, so that more and more of the organization's resources are steadily applied to the problem in the pursuit of its resolution.

According to Kepner-Tregoe's Mike Bird: ‘Most organizations have a blurred escalation process that's driven by perceptions of expertise. And the support organization is structured according to those perceptions.' In other words, organizations' structures and processes are based on how people believe problems are solved, rather than direct, objective evidence of the reality.

Sun's support approach had developed alongside its product and service set. However, the business value of its offerings had begun to change in the customers' perceptions, and not always in line with Sun's own preconceptions. Many businesses had moved online - a development partly inspired and encouraged by Sun itself - and now relied heavily on their systems for business survival. Traditional back-office functionality was now being operated directly by customers. If that functionality failed, the bottom line registered the failures immediately. Problems now attracted much greater exposure than in the past.

The existing support structure used four escalation levels. Level 1 comprised call handling. At this stage, incoming problems would be logged and routed to generalists at level 2. A generalist would be able to address common problems within defined standard response times. A typical example would be remedying a well-understood Unix problem within a 15-minute call-back period.

The support structure's level 3 was made up of product specialists. These specialists were trained in particular Sun products, such as its enterprise servers. In most cases level 3 specialists were grouped within a Sun country organization, although in some territories level 3 staff were shared at a regional basis.

The fourth level was the backline: Sun's engineering gurus. Level 4 specialists form an elite corps drawn from the teams that create Sun's hardware and software. They were used to taking support calls from all over the world, but did not interface directly with customers.

Sun was finding that in the lower levels of its escalation structure, many of the easier problems needed to be fixed faster. With Sun boxes taking enterprise-critical roles, quick fixes needed to be quicker. The company therefore brought in a knowledge base and a range of support tools. These remedies gave level 1, 2 and 3 staff faster access to the organization's knowledge, streamlining its ability to respond to the classes of simpler, well-described problems. However, the new tools did not address efficiency and effectiveness at level 4.

By running a troubleshooting pilot in two sites, the joint team discovered that the problem affecting the level 4 handover was bound up with the quality of information contained in the transition. At this point in the escalation, the problem effectively became invisible as the interfacing teams attempted to communicate without a shared language. The organization suffered from what Sun called ‘escalation ping-pong' as colleagues batted undefined problems between themselves. Level 3 staff would take a problem to level 4 colleagues precisely because they did not understand the problem. But level 4 staff could not grasp the problem because their level 3 counterparts could not describe it.

One of the team's insights is that problem-solving loses visibility because it is conducted privately and silently by experts. Bird says: ‘The quality of the solving is invisible because the diagnosis is going on in their heads, and their outputs are questions and suggestions.'

The sources of the experts' comments remain obscure to the person with whom they are working, leading to a lack of shared understanding and trust. In a situation lacking a tangible, shared agenda, it is easy for the belief to arise that every problem is unique.

Information in transit

Sun use the example of medical experts to explain how problem-solving actually works, and its generic features. A doctor making a diagnosis asks lots of questions, most of which will seem baffling to the patient. However, the doctor is not asking questions at random. His or her questions are designed to rule out areas of enquiry as quickly as possible. The diagnostic process is one of pruning: carefully discarding those branches of the solution tree that are not relevant to the case in hand.

Medicine also provides a good example of how clear information sets assist in handovers between levels in an escalation process. For example, at the scene of an accident a police officer will use first aid skills to make the victim safe and comfortable, and report to the paramedic a defined set of information, including the time elapsed since the accident, any obvious wounds and any observed behaviours. For their part, the ambulance team will make a next-level report to the receiving medical team at the hospital. This team's report will include data on vital signs and the results of any first-line tests they have completed during the journey. The information package delivered alongside the patient is standardized and acceptable throughout the medical profession within a country. This practice of capturing diagnostic data at each escalation level is repeated throughout the healthcare profession, notably at the interface between general practitioners and consultants. This particular professional interface is similar to the level 3-4 handover point at Sun.

The hard graft of making change in organizations comes down to influencing the day-to-day, minute-by-minute behaviour of a large number of individuals: individuals with opinions, experience and pride. Computer engineers, in particular, live with a stereotyped view of their profession that casts them as uncommunicative and arrogant. Managing such individuals, and suggesting that their working practices can be improved, requires sensitivity and openness - and the ability to see beyond limiting stereotypes. Steve White, an engineer himself, was not encumbered by prejudice. But he was aware that querying the processes of any professional risks damaging organizational relationships and delivery: ‘Sun's engineers are among the best in the world. How could we persuade these engineers to change the way they work on the most complex and difficult problems? And do so without damaging the great work they are already doing? There was more to the solution than training.'

The answer came in two parts. The first part was the concept of triggers. A trigger is a defined point in the call workflow when an engineer should use the new process. So, when a country engineer has spent a short time trying to solve a problem on his or her own and then wants to escalate the call to the worldwide backline, the trigger asks for the problem data to be handed over in the precise format defined by the team. Every problem call passed to the backline now contains answers to the same questions, in the same format, regardless of the technology of the problem.

The data format combines questions that together isolate and compare the problem. Basic questions formed around ‘What …', ‘Where …', ‘When …', ‘How big …' and so on provide structural elements to the problem definition. Comparison questions help to refine further the problem boundary and distinguish it from unrelated problems with which it might have surface similarities. For example, if the answer to a ‘What' question is ‘Box A is broken', then a follow-on comparison question might be: ‘Is Box B broken?' The method uses logical operators such as ‘is not' to explore the space around the problem.

The method also uses scale to narrow down various dimensions of the problem. For example, when exploring the time attributes of a problem, the user may be asked: ‘When did Box A break down this time? When has it broken down in the past? How many times has it broken down in its lifetime?' Again, these are very similar questions to those asked by a doctor seeking to establish a historical context for a current condition.

A troubleshooting environment

The new information format and the triggers associated with its use provided the vehicle for the improvement Sun needed to make. Achieving a change in actual practice required further actions. As Roy Garcia, Sun's leader of the SGR troubleshooting method in the United States says: ‘Sun engineers are smart, practical and experienced people. We needed to set up the process so that the engineers wanted to use it and so that customers saw the benefit as quickly as possible.'

Applying triggers meant extra work for country engineers - but the backline (and the customer) would see the benefit, not them. What would country engineers get in return?