The Two Dimensions Of Helping To Learn

The Two Dimensions Of ‘Helping To Learn'

The core model of mentoring - the dynamic that drives a high proportion of the schemes and programmes around the world outside the USA - derives from two key relationship variables.

The first of these is ‘Who's in charge?'

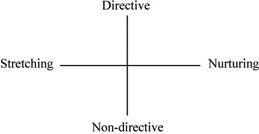

If the mentor takes primary responsibility for managing the relationship (by deciding the content, timing and direction of discussion, by pointing the mentee towards specific career or personal goals, or by giving strong advice and suggestions), then the relationship is directive in tone. If he or she, by contrast, encourages the mentee to set the agenda and initiate meetings, encourages the mentee to come to his or her own conclusions about the way forward and generally stimulates the development of self-reliance, then the relationship is relatively non-directive (see Figure 2). Support for this dimension of helping behaviour comes from a variety of resources both within the mentoring literature and in the parallel literatures on counselling and coaching as well as interviewing and appraisal.

Figure 2: Two dimensions of helping

For example, Barham and Conway's (1998) study of the influence of cultural factors on mentor behaviour concludes that where managers expect their normal role to be that of expert,

The style of the mentoring relationship will be more didactic and less empowered from the mentee's perspective.

Where the culture expects managers to be facilitators, however,

The balance of the relationship will be more equal and it will be about mutual learning and sharing. There will be an empowered ‘feel' to the mentoring relationships.

Recent studies suggest strongly that the most effective relationships in which personal development is the desired outcome are those in which the mentee is relatively proactive and the mentor relatively passive or reactive. The opposite is probably true for relationships that are more focused on sponsorship behaviours.

The second dimension relates to the individual's need.

Is it primarily about learning - being challenged and stretched - or about nurturing - being supported and encouraged? Again, this is a dimension well established in the general psychological literature, and in particular that on leadership. Blake and Mouton (1964), Schriesheim and Murphy (1976), Likert (1961) and others emphasise the importance of both task orientation and consideration/social support in achieving group goals. The effective mentoring relationship similarly requires a mixture (often shifting with the needs of the mentee) of task-focus (for which read challenge or stretching) and supporting behaviours (for which read nurturing). Authors such as Darling (1984) refer to both types of behaviours in their descriptions of what mentors do.

The stretching/nurturing dimension also reflects the complex duality of the goddess Athena - the real mentor in the Greek myth. She is at the same time the macho, fearsome huntress and the nurturing Earth Mother. Athena, who was closely associated with the owl as a symbol of wisdom, was frequently depicted in full armour and even was supposed to have been born fully armed! Yet she was also closely associated with handicrafts and agriculture. It is tempting to view these as masculine/feminine characteristics, and some writers have done just that. However, in my experience this can all too easily lead people into styles of mentoring behaviour based on gender stereotypes. The essence of effective mentoring is that mentors have the facility to move along the dimensions, in any direction, in response to their observation of the learner's need at the time.

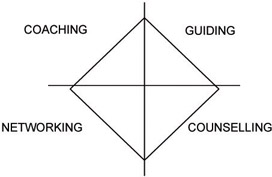

The beauty of this model is its combination of simplicity and inclusiveness. All ‘helping to learn' behaviours fit within these broad dimensions. (‘Teaching' is not necessarily a helping-to-learn behaviour per se - being taught is something that is done to you, whereas learning is something you do yourself, or with someone else. ) We can isolate four primary ‘helping to learn' styles based on the dimensions (see Figure 3), on which a fifth is based.

Figure 3: Four basic styles of helping

Coaching

Coaching is a relatively directive means of helping someone develop competence. It is relatively directive because the coach is in charge of the process. Although there are, in turn, four basic styles of coaching, which range from the highly directive to more stimulative, learner-driven approaches, it is common for the learning goals to be set either by the coach or by a third party. In the world of work, coaching goals are most frequently established as an outcome of performance appraisal. The issue of learner commitment (is this really what matters to them?) is therefore relevant. Some of the useful behaviours effective coaches may display include challenging the learner's assumptions, being a critical friend and demonstrating how they do something the learner is having difficulties with.

Counselling

Counselling - in the context of support and learning, as opposed to therapy - is a relatively non-directive means of helping someone cope. By acting as a sounding-board, helping someone structure and analyse career-influencing decisions, and sometimes simply by being there to listen, the mentor supports the mentee in taking responsibility for his or her career and personal development.

Networking

To function effectively within any organisation, people need personal networks. At the very least they need an information network (how do I find out what I need to know?) and an influence network (how do I get people, over whom I have no direct control, to do things for me?). The same is true for the unemployed young adult in the context of community mentoring, for newly recruited researchers at university and for people in many other situations where mentoring can be applied. Effective mentors help their mentees develop self-resourcefulness by making them aware of the plethora of influence and information resources available to them - people, organisations and more formal repositories of knowledge. They may make an introduction to someone they already know, or talk the mentee through how he or she will make his or her own introduction to that person, or help the mentee build entire chunks of virgin network.

Guiding

Guiding (effectively acting as a guardian) is another relatively hands-on role and is the one most managers find easiest because it is closest to what they do normally. Giving advice comes naturally. It is unfortunate that so many managers who have attended coaching courses or read well-meant books on the developmental role of the supervisor come away feeling guilty, or worse, that they have to constantly restrain themselves from giving straight answers to their direct reports. The reality is that there are many situations where asking ‘What do you think you should do?' is not an appropriate response. Using the tools of reflective analysis at inappropriate times is likely to have a far greater demotivating effect than simply leaving well alone. Equally, however, always providing the answer is not going to help someone grow. Because being a guide/guardian tends to carry with it a relatively strong element of being a role model - an example of success in whatever field the learner has chosen to pursue - one's behaviours, good or bad, are likely to be passed on to the learner along with more practical support. At an extreme, guide/guardians become sponsors or godfathers, taking a very direct interest in the learner's development, putting the learner forward for high-profile tasks, tipping him or her off about opportunities and actively moulding the learner's career. This can be very stifling for the recipient, who may not be in a position to resist this largesse should the learner prefer to succeed by his or her own resources. If learners comply with the mentors' manipulations, a subtle psychological contract often emerges in which career progression is traded for loyalty and respect. Some cultures regard this more positively than others.

Mentoring

Finally, mentoring draws on all four other ‘helping to learn' styles. Indeed, the core skill of a mentor can be described as having sufficient sensitivity to the mentee's needs to respond with the appropriate behaviours. Thus, the effective mentor may use the challenging behaviours of stretch coaching at one point and the empathetic listening of counselling a short while later.

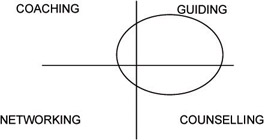

Where an organisation, or a national culture, or a mentoring pair, decide to draw the boundaries of what is appropriate behaviour for a mentor may vary substantially. What we call developmental mentoring assumes a diamond across the middle of the diagram (Figure 4). Traditional US mentoring, by contrast, is concentrated on a circle centred in the top right-hand corner (Figure 5), and often encompasses a high level of sponsoring behaviours.

Figure 4: Developmental mentoring

Figure 5: Sponsoring mentoring

Table 1 (next page) explains the distinction between developmental and sponsoring mentoring in more detail. Essentially, one emphasises empowerment and personal accountability; the other the effective use of power and influence.

| Developmental mentoring | Sponsoring mentoring |

|---|---|

| Mentee (literally, one who is helped to think) | Protégé (literally, one who is protected |

| Two-way learning | One-way learning |

| The power and authority of the mentor are ‘parked' | The mentor's power to influence is central to the relationship |

| Mentor helps mentee decide what he/she wants and plan how to achieve it | Mentor intervenes on mentee's behalf |

| Begins with an ending in mind | Often ends in conflict, when mentee outgrows mentor and rejects advice |

| Built on learning opportunities and friendship | Built on reciprocal loyalty |

| Most common form of help is stimulating insight | Most common forms of help are advice and introductions |

| Mentor may be peer or even junior - it is experience that counts | Mentor is older and more senior |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 124