What Causes Conflict?

There are two primary sources of conflict among people, in both their personal and business relationships: individual differences and stylistic clashes . In business relationships, a third factor contributes to the generation of conflict: organizational conditions.

Individual Differences

No two human beings ”not even identical twins ”are alike in all aspects. No big news here. Each person is unique, and uniqueness implies differences. As a result, all of us bring to relationships different:

-

Wants and needs

-

Values and beliefs

-

Assumptions and interpretations

-

Degrees of knowledge and information

-

Expectations

-

Culture

When we encounter other people whose wants and needs, values and beliefs, assumptions and interpretations differ from our own, we may find ourselves in conflict with them. But that does not mean that we must "butt heads." People can have differences without taking them personally , and one of the keys to successfully managing conflict is learning to depersonalize it, or to view it as a business case .

Most of the differences previously mentioned are fairly universal and easily understood . Culture, however, is a far more complicated source of conflict than the others. It may be that culture plays a pivotal role in determining how conflict expresses itself, both between individuals and in groups. Some cultures, at least stereotypically, are said to be conflict-averse, preferring to sidestep controversy to preserve peace and promote the common good. We suggest using caution with these stereotypes.

Germany is touted to be a place where, even today, leaders brook little disagreement , much less overt conflict. Recently, one group of twenty-five German managers was working on its conflict-resolution skills. The company's director of human resources described the group 's leader as " harsh , rigid, and judgmental." According to this individual, anyone who wanted to help this group to improve its performance had to first understand that "Germans don't criticize their leaders. They go along with them out of respect." Given his international experience in conflict management, the facilitator leading the effort was skeptical. He knew that you cannot "respect away" conflict, although you might try to submerge it.

At the initial team meeting, the facilitator turned to the leader and advised him to be open , to admit that he valued candor, and to encourage everyone to be honest. The leader readily agreed. "What's important," he told the group, "is that we come out of here with a better sense of how we need to operate and how I can be a better leader."

This opened up the floodgates. For the first time, team members told their leader how much they resented the fact that decisions were handed to them as faits accomplis . They said they were tired of only being seen; they wanted to be heard . They told their leader that he needed to respect their contribution to the business. The leader not only accepted their open criticism of him but thanked them for their candor. He promised to do better in the future, thereby paving the way for a new way of interacting with them. So much for stereotypes!

Individual and Perceptual Differences

Individual differences are often the result of differences in perception. People often say that perception is reality, but in fact, perception is only a partial reality ”ours and not the other person's. And it is on our perception that we base our wants, needs, values, beliefs, and so forth.

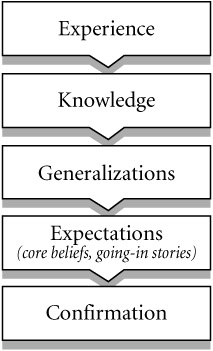

Perception tends to evolve in the same way for all of us. As we go through life, we accumulate experience ”some positive, some negative. From that experience, we develop our knowledge base. If, for example, you have a great experience with a winning team, then you "know" that teams can accomplish more than a single contributor . But a bad experience deposits a different data point in your memory bank: You "know" that working in a team creates stress, slows down productivity, and produces mediocre outcomes .

We tend to generalize what we learn from our experiences, and these generalizations form our perceptions. So, if you have knowledge of a positive team experience, you might have a perception that teamwork is a good thing. Conversely, if you have knowledge of a disastrous team outcome, you might develop a negative perception of teamwork.

The Power of Going-In Stories

Perceptions create expectations , or core beliefs , about what will happen when we enter a situation similar to the one we have already experienced . These, in turn , give rise to what we call " going-in stories ." Based on my experience, if my core belief is that teams work well, I will be more likely to enter a team situation with the going-in story that differences among team members should be viewed as constructive challenges and a way to create better goals and outcomes. If my core belief is that teams do not work well, when I see team members challenging one another I will probably tell myself the story that this is merely another example of group chaos and the outcome will likely be negative. I will probably become argumentative and defensive, thereby increasing whatever tension may already exist. In other words, I tend to look for evidence to confirm that my core belief/story is valid, then behave accordingly . My continued resistance to team efforts helps to perpetuate the tension in the group, which adds to my knowledge base that teams do not work, and thus the cycle repeats itself.

This process is represented in Figure 1-1:

Figure 1-1: The Evolution of Perception.

We rely on our perceptions to guide us through our interactions with others. The trouble occurs when we act in accordance with our perceptions, but there is a disconnect between our view of things and the views of those with whom we are dealing. By not opening ourselves up to data that broadens our perspective, we become prisoners of our perceptions. Our core beliefs turn into " core limiting beliefs ," and by holding on to them, we lock ourselves hopelessly into ongoing conflict. Our objective becomes not to seek common ground but to prove that our perception ”our core limiting belief ”is the right one. To this end, we develop going-in stories that become self-fulfilling prophecies.

In a business situation, going-in stories can revolve around people's sense of self and others, their feelings about their function, or their interpretation of the organization as a whole. Recently, when the global team of a large food products corporation met to work on its conflict-resolution skills, a female executive in her forties, who had been with the company for three or four years , shared with the group her feeling that she often was not taken seriously by the others because she was viewed as being "too young" or "the new kid on the block." This perception, she revealed, often kept her from offering suggestions and giving opinions , even when she felt strongly about issues. She was taken aback when the members of the group told her that they had never considered her too inexperienced and, indeed, valued her perspective. It was her own going-in story, not the view of her colleagues, that limited her effectiveness.

People's perceptions are often limited by their positional role and are influenced by supporting systems such as the performance management and rewards processes. This sets the stage for conflict before they even begin to interact with those in other functions.

Peter Wentworth, vice president of global human resources for Pfizer's consumer health care division, illustrates this point when he discusses the perceptions of his organization's regional players:

Regional players have the potential to be very territorial. Their going-in story is that the best way to drive global growth is by growing their own region. So they attempt to optimize what they do individually. Yet, the people who run the global category are the ones who have responsibility for driving global growth. The global head of oral care, for example, will say, "This is where we need to be investing; these are the product lines that we need to grow; this is how we need to balance our global portfolio and allocate resources across the various geographies." But, given his going-in story, the regional head is likely to respond with, "I know what our customers need, and in order to meet our growth goals we are going to do 'A.' I know you want to do 'B,' but that's just not a priority for us."

Wentworth knows that it is difficult to avoid conflict when people's going-in stories are so parochial. He concludes,

Evolved team leaders know, however, that such conflict can be managed. The key: changing the going-in stories of all the individual players so that they perceive themselves first and foremost as members of a global team who share common goals and only secondarily as regional, category, or functional executives.

Sometimes an entire organization will subscribe to a going-in story about the limits that exist within the organization and the punishment that is likely to be meted out to anyone who dares to cross the line. In many cases, these stories no longer have any foundation or never did, but they are perpetuated nonetheless and can deaden creativity and morale . One vice president of marketing shared an example of this type of going-in story:

Several years ago, we had a president who made all the calls himself and wasn't open to change. He did not allow individuals to voice their opinion, and many people were intimidated and, therefore, never challenged him. People who did weren't very successful. As a result, there was a lot of fear about speaking up. Today, even though we have had two presidents since he left and our current president has done a lot to encourage candor, we still hear stories about people being afraid to speak their mind. When you begin to drill down and try to understand what it is all about, why it exists, you find out that it has to do with the way people were managed then. But it held us back until we were able to successfully work through our stories.

There is a way to avoid being trapped by your going-in story: Use the input of others to build, modify, test, and perhaps abandon perceptions. By asking other people for their opinions and by probing how those opinions were formed , we open ourselves up to entirely new ways of looking at the people and events around us.

To successfully manage conflict we must also be willing to share our perceptions with others ”to tell them exactly what we value and what we expect from them. Only when each party opens up to the other, revealing their perceptions, can conflict be resolved ”which brings us to the second factor that often generates conflict: stylistic clashes.

Stylistic Clashes

If you master the skill of sending and receiving clear messages, you hold a key to forging successful relationships, from marriage to the workplace.

Communication may be the one area where style is not only sizzle but substance. When we talk about style, we are referring to how each individual approaches interpersonal communication. Some people are comfortable revealing their innermost thoughts and feelings, while others find it extremely awkward and embarrassing to open up, especially in front of a group. The fight-like-cats-and-dogs-and-then-kiss-and-make-up style works for many couples ”and many business partners ”while others are appalled by such unabashed displays. Our style of interacting with other people can often be traced back to our ethnic roots. In Australia and the United States, greeting a business acquaintance with a slap on the back and a "How ya been?" is perfectly acceptable. But do not try backslapping in Japan!

Effective communication is critical for resolving differences, and each one of us needs to be aware of how we communicate. What is our primary style? Do we use it some, all, or most of the time? Do we vary our style depending on the situation? The person we are currently communicating with? The issue that is on the table?

Although human behavior does not lend itself to neat typologies, we have found it helpful to think about the method we use to communicate in terms of three broad styles: nonassertive , assertive , and aggressive . We will discuss the three styles ”and how a person can move among them ”in detail in Chapter 5, but we would like to point out here that one of the toughest tasks is accurately identifying your own personal style.

For example, one important exercise that occurs during a conflict-resolution session involves asking the team members, one by one, to pinpoint where on the continuum from nonassertive to assertive to aggressive they believe their behavior generally falls . The facilitator then asks each of the other team members to comment on the person's self-assessment. The results are often revealing.

On one high-level cross-functional team, a manager named Dan rated himself highly assertive, as represented by the x on the behavioral continuum shown in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2: The Behavioral Continuum.

When the rest of the team discussed Dan's self-assessment, it quickly became apparent that there was a fairly large disconnect between his image of himself and theirs. The majority of the group said that they considered Dan to be very aggressive. They pointed to his intensity and the fact that he was "wound tight." They said that when he presented his viewpoint he was not open to discussion or critique. One or two of his colleagues confessed that they felt intimidated by Dan. The group's average assessment of Dan is represented by the y at the far right of the continuum.

Dan was surprised by the disconnect between his assessment of himself and that of the group, and this gave him new insight into the way he was communicating with other people. It is not always easy to see ourselves as other people see us, but until we do, our perceptions will remain limited ”and limiting.

The behavioral continuum applies not only to individual managers but also to organizations. In one Northeast-based financial organization, for example, the culture was squarely on the far right (or aggressive) side of the continuum. When the organization implemented a new performance-management system, the divisional CEOs knew that they needed to move toward becoming more collaborative. This meant abandoning the winner-take-all mentality that had long characterized their behavior. The biggest challenge, it turns out, was getting the CEOs' team members to express their legitimate differences of opinion with their leaders. For too long, they had been cowered into submission.

By discussing the behavioral continuum, the CEOs quickly saw that different behaviors on the continuum can have very different consequences. For example, the overarching aggressive style of the CEOs had led to the formation of underground resistance armies that had quietly sandbagged divisional decisions. With this insight, the CEOs moved to a less aggressive, but more assertive point on the continuum and this, in turn, led to more open and honest discussion and debate.

Organizational Conditions

The conditions under which we work can be a significant conflict producer. Hierarchical structure, policies and procedures, performance reviews, reward systems, organizational culture, and even physical plant conditions can, on occasion, turn even the mildest-mannered employee into a raging bull.

Adding to the stress is the fact that today's companies are matter in motion, to paraphrase Thomas Hobbes. Downsizing, rightsizing, restructuring, reengineering, delayering ”you name it ”continue on as an unending parade of changes within most organizations. This constant churn increases the potential for disagreement. Executives frequently find themselves competing for resources, clarifying roles and procedures, setting standards, and establishing goals and priorities. Change, by its very nature, tends to put the status quo on trial. No sooner are resources allocated, roles clarified, and goals established then along comes a new change initiative, and the wrangling begins anew.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 99