How to Field a Survey

|

Before you start designing a survey, you need to know what you're trying to accomplish. Start by writing a sentence or two about why you're doing this survey—your goal. For example, say that you have a mature product, a Web site that's been around for several years, and although revenue has been decent, the rate with which new people have been finding your site has been slowing down. You have an idea of the size of your market, but that's assuming that your market has not changed, that the kinds of people finding your site now are the same as when the site launched. Further, although your site has some unique features, it has several competitors that have similar feature sets. You've been counting on your unique features to drive customers and although the log files show that the features get used, it's difficult to tell whether they're the reason people use your product or whether they're icing on the cake. Completing the sentence "We are going to run a survey," the reasoning could read as follows:

To understand if our user base has changed since last year, and if so, how; and to understand which features they find most attractive.

Setting the Schedule

Once you've decided on the overall goal for the survey, you need to construct a schedule. Since the preparation of a survey is critical to its success, a typical survey research schedule includes enough time for questions to be written and reviewed, and for the survey to be tested and revised as necessary (Table 11.1). Once a survey has been sent out, no changes can be made to maintain statistical validity, so preparation time is crucial.

| Timing | Activity |

|---|---|

| t - 3 weeks | Determine test audience, goals. |

| t - 3 weeks | Start writing questions and preparing collection software. |

| t - 2 weeks | Finish writing questions, review with a few people. Rewrite as necessary. Write report draft. |

| t - 1 week | Finish collection software preparation. Begin building survey site. Pilot test, using both collection and tabulation software. Write report based on pilot test results. |

| t - 3 days | Rewrite questions based on pilot test feedback; review with a couple of people. |

| t - 2 days | Finish preparing site with software and questions. Test site for functionality under multiple conditions. |

| t | Field the survey (usually 1–14 days, depending on whether there's important daily variation). When done, remove the survey site immediately and shut down data collection. |

| t + 1 day | Begin analysis. |

| t + 3 days | Complete analysis. Begin report. |

| t + 1 week | Complete report. Present to development team, discuss, and note directions for further research. |

Writing the Survey

You should start by enumerating the goals of your survey as specifically as possible, based on your primary reason.

-

Create a demographic, technological, and Web use profile of our audience.

-

Get a prioritized rating of the utility of our main features to the survey audience.

-

Get a list of other sites they commonly use.

With this list, you should have enough information to choose the kind of survey you're going to be fielding.

Brainstorm Your Questions

With the survey goals in mind, brainstorm your questions (you can do this by yourself or with a group).Without stopping, write down every question you can think of that you want to answer with the survey. Don't try to phrase them in "survey-ese," just write down what you want to know.

As you're brainstorming, keep in mind that there are two different kinds of survey goals, descriptive and explanatory.

Descriptive goals aim to profile the audience. They summarize your audience's composition in terms of their personal characteristics, their computer setup, what they want, and how they claim to behave. Although such profiles can be quite extensive and sophisticated, they do not attempt to understand how any of the characteristics affect each other.

Explanatory goals explain people's beliefs and behaviors by uncovering relationships between their answers. For example, a mostly descriptive survey would seek to know which features people use and what their average incomes are, whereas an explanatory survey would try to explain how the size of their income affects the features they prefer. Such goals aim to find inherent relationships between characteristics. The more these relationships can be isolated, the more precise the explanation.

Survey questions themselves come in a variety of flavors. General question categories can be divided into characteristic questions that describe who someone is and what his or her physical and software environment is like, behavior questions that outline how someone behaves, and attitudinal questions that inquire into what people want and believe. Each of these major categories can have lots of subcategories.

Characteristic Categories

-

Demographic. These are questions about who the respondents are. How old are they? What do they do for a living? How educated are they?

-

Technological. These questions ask about their computer setup and experience. What operating system do they run? What is their monitor resolution?

Behavioral Categories

-

Web use. These questions ask people how they use the Web. How long have they been using it? How often do they use it every week? What kinds of things do they use it for? How much computer experience do they have?

-

Usage. What product features do they (claim to) use? How often do they use them? What are the reasons they come to your site? How long have they been using it? These are behavioral questions.

-

Competitive. What other sites do they visit? How often? How long have they been using them? What features do they use?

Attitudinal Categories

-

Satisfaction. Do they like your site? Does it do what they had expected? Are they able to do what they want with it?

-

Preference. What do they find most compelling? Which features do they tell their friends about? What do they consider unnecessary or distracting?

-

Desire. What do they want? What features do they feel are lacking?

Now, with your list of questions in mind, ask other members of your development team to come up with a list of their own. You may want to show them your list, but first ask them to do it from scratch so that they're not biased by your ideas. Then, when you've collected everyone's questions, share them and see if any additional questions appear from the mix.

The list could look like this.

How old are you?

How much do you make?

What's your education level?

What operating system do you use?

Have you ever heard of Linux?

Have you ever used Linux?

How often do you use the Automatic Alarm?

Do you ever use Ebay? Yahoo! Auction?

What speed is your connection?

How much time do you spend on the Web?

How long are you willing to wait to get an answer?

Have you ever used Quicken?

How long have you had your current computer?

How long have you been using the Net?

What's the most important thing to you when it comes to a Web site?

What time zone do you live in?

etc.

Write the Questions

Ask people only questions that they are likely to know the answers to, ask about things relevant to them, and be clear in what you're asking. The danger is that people will give you answers—whether reliable or not.

—Earl Babbie, Survey Research Methods, p. 133

Now it's time to write the questions. In Chapter 6, there are a number of rules for asking nondirected questions, questions that don't lead the person answering them to think that there's a "right" answer. Most of the suggestions in that section concentrate on the moderator's immediate behavior and helping staying nonjudgmental, but they apply equally well to survey questions. However, whereas qualitative research questions need to be flexible not to cramp respondents' answers, survey questions need to be more precise and restricted in order to be countable. Unlike most interviews, where the questions should be open-ended (in other words, they should not limit the set of responses to a list compiled by the interviewer), most survey questions are close-ended by pragmatic necessity. In general, open-ended questions require much more effort from the person answering them and from the analyst. This is desirable in long interview situations with a few people, but much more difficult in a survey situation when there may be potentially thousands of participants. Open-ended questions may be used in surveys—they can provide answers in situations where you have no idea how to write the question in a close-ended way—but they need to be used carefully and sparingly.

The most common type of close-ended survey question is the single-answer multiple-choice question. We've all seen this type of question: it has a range of choices for the respondent, only one of which may be picked.

How long have you been using Internet email?

| ○ | Less than a year |

| ○ | 1–2 years |

| ○ | 2–5 years |

| ○ | 5 years or more |

Another common type of question is the checklist. This question consists of a list of answers, any number of which can be chosen.

What kinds of stories have you read in Wired News in the last week? (check all that apply)

| q | Telecommunications |

| q | New products |

| q | Hackers |

| q | Fashion |

| q | Travel |

| q | Hardware reviews |

| q | Software reviews |

| q | Predictions |

| q | Sports |

| q | Industry analysis |

| q | Political commentary |

| q | Fine arts |

| q | Fiction |

| q | Investment |

| q | Personality profiles |

| q | Other |

| q | I haven't read any Wired News stories in the last week |

In order for close-ended questions to be comfortably answerable by the respondents, the answers to them need to be specific, exhaustive, and mutually exclusive. Specificity reduces the amount of uncertainty when the time comes to analyze the answer. If your audience consists of dance music DJs and you're asking about what kind of music they spin, it may be important to make sure that you don't just ask about "dance music" when the DJs may distinguish between two dozen different subgenres. Exhaustive questions reduce the respondents' frustration, and they reduce errors because people won't be as likely to choose a random answer when they can't find one that represents what they really mean. An exhaustive question features all the possible answers. If you can't make an exhaustive list of answers, the question should not be close-ended. Answers should also be as mutually exclusive as possible to reduce the amount of uncertainty among the choices. If you're asking where people shop and you give them the option to choose between "in my neighborhood" and "nearby," they may not know the differences that you had in mind.

Obviously, close-ended questions limit the kinds of questions you can ask, so rephrase your questions so that they can be asked in a close-ended way, and eliminate the ones that can't be rewritten.

Now, make a grid with four columns. For each question, write the question, the instructions you're going to give to the respondent, the possible answers, and why you're asking the question. The "reasons" column is especially important because you need to make sure that you have a specific justification for each and every question. Why is it important? What is the information going to be used for? Who wants to know?

| Question | Instructions | Answers | Reasons |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is your age? | None. | Pop-up: Under 13 13–18 19–20 21–24 25–34 35–44 45–54 55 and over | For comparison with last year's survey. Compare with experience. |

| What is your gender? | None. | Pop-up: Male Female | For comparison with last year's survey. |

| What kinds of stories have you read in Wired News in the last week? | Check all that apply. | Checklist: Telecommunications New products Hackers Fashion Travel Hardware reviews Software reviews Predictions Sports Computer industry analysis Political commentary Fine arts Fiction Investment Personality profiles | A measure of reader information desires. Compare perceived reading habits to actual behavior based on log analysis. Summarize for ad sales. |

| What operating system do you use most frequently to access the Web? | None. | Pop-up: Windows XP Windows 2000 Windows 95/98 Windows NT Macintosh Linux Other Don't know | Compare with last year's survey. Compare with log analysis. Summarize for design. Summarize for editorial. |

| Note | In some cases, people may have little or no appropriate past experience to base their answers on. For example, the process of buying a home (or getting open-heart surgery or enrolling in a university) is relatively infrequent for most people, and their past experience may have little relation to their future behavior. This is the one time when asking a hypothetical question may be better than asking about past behavior since past behavior would unlikely yield any useful information. |

You may also want to make a second list of information that can be gathered automatically. Web server log files can collect the time a survey was taken, the operating system of the machine used to take the survey, the kind of browser they were using, what Internet domain the machine was on, and so on. Cookies can keep track of who has visited your site before, who has purchased from you before, what their preferences are, and the like.

When writing questions, don't make people predict their behavior. People's past behavior is usually better at predicting their future behavior than their statements are. Unless you're asking about a completely novel concept, keep your questions focused on how people have actually acted in the past, not how they can imagine themselves acting in the future. If you're interested in whether someone would use an online scheduling system, don't ask

Will you use an online scheduling system?

Ask instead

Have you ever used or ever wanted to use an online calendar system such as Yahoo! Calendar or eCalendar?

Avoid negative questions. Negative questions are more difficult to understand and easy to mistake for the positive versions of themselves.

Which of the following features are you not interested in?

can be easily read as

Which of the following features are you interested in?

It's much easier to ask

Which of the following features are you interested in?

and then to infer the ones that are not checked are uninteresting to the respondents.

Don't overload questions. Each question should contain at most one concept that you're investigating. Although multiple concepts may be linked, they should still be divided into separate, clear individual questions. Compound questions are frustrating for the respondent, who only agrees with half of the question, and more complicated for the analyst, who needs to infer the respondent's perspective on both parts of the question.

Do you find yourself frustrated at the Internet's performance because of bandwidth problems?

can be rewritten as

Are you frustrated by the Internet's performance?

If so, which of the following aspects of Internet performance frustrate you?

| q | Page length |

| q | Download time |

| q | Picture size |

etc.

Be specific. Avoid words with multiple or fuzzy meanings ("sometimes," "around," "roughly," "any").When speaking in units other than money, percentages, or other common abbreviations, make sure that the whole name of the unit is written out ("hours" instead of "hrs.," "thousands" instead of "K," etc.). Use exact time periods.

So rather than writing a question about how often someone reads news as

How much time have you spent reading news on the Web recently?

| ○ | Some |

| ○ | A lot |

| ○ | Every day |

etc.

the question can be written as

How much time did you spend reading news and information on the Web in the last week?

| ○ | None |

| ○ | 0 to 5 hours |

| ○ | 6 to 10 hours |

| ○ | 11 to 20 hours |

| ○ | More than 20 hours |

Never shut people out. Questions should always give people an option that they feel applies to them. This question, for example, assumes a lot of things about the respondents and their attitudes.

What do you love most about Wired News?

It should be rewritten as

Which of the following features are important to you in Wired News? (check all that apply)

The latter phrasing avoids most of the problems with the earlier question—especially if it provides an option for "None"—and provides most of the same answers.

Stay consistent. Ask questions the same way every time. This means more than just using similar wording for similar questions. You should also strive to maintain consistency in meaning in the order of answer options and in the way the questions are presented.

Avoid extremes. Extreme situations rarely happen, and most people infrequently find themselves exhibiting extreme behavior, so avoid situations that require or imply the need for extreme behavior.

Do you check online news every time you surf the Web?

This would probably produce almost exclusively negative responses since it's likely that only a few people check news every single time they surf. A better way would be to ask

How often do you check online news?

| ○ | Several times a day |

| ○ | Once a day |

| ○ | More than once a week |

| ○ | Once a week |

| ○ | Once a month |

| ○ | Less than once a month |

| ○ | Never |

and compare the responses to how often people say they surf the Web to see the proportion.

Make questions relevant. If people are confronted with a list of questions that don't relate to their experience or their life, they're not likely to finish the survey. For example, a group of computer service technicians will respond differently to questions about the minutia of their computer configuration than will a group of taxi drivers. If the respondent can't answer many of the questions or if they're not interested in the answers, they're not likely to be interested in finishing the survey.

Use Likert scales. Likert scales are a familiar method of presenting multiple-choice answers. They consist of a statement or series of statements followed by a choice of three, five, or seven options (most surveys use three or five) that define a possible range of answers, including a neutral middle option.

Rate the following aspects of news and information Web sites for how interesting they are to you.

| Very interesting | Somewhat interesting | Neutral | Somewhat uninteresting | Very uninteresting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | |||||

| The number of different stories on a given topic | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The number of different topics covered | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| How quickly the page downloads | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The reputation of the news outlet | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| How comprehensively each story is covered | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| A unique editorial perspective | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The quality of the site's search engine | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The visual appearance of the site | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| How quickly stories are covered after they happened | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| How easy it is to get around in the site | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Create follow-up questions. When technologically possible, ask questions that further expand on a given answer. Ideally, follow-up questions should appear only after a specific answer for a given question. This is technologically possible with some online survey systems. When it's impossible, it should be clear that the follow-up questions are related to a given answer and that they should not be answered otherwise.

If one question asks

Check all the sites that you read regularly.

A follow-up can then contain a list of sites that were marked as being read regularly.

Rate how important each of the following sites are to you, from "Crucial" to "Unimportant."

| Note | A list of common questions is provided in the Appendix. However, don't hesitate to experiment with new questions and question types. Much online research still shows its roots in the paper survey world, with online questions essentially the same as their printed ancestors. Using the technology offers a lot of possibilities for innovative questions. A simple example: rather than asking people for the size of their Web browser window (something that many people may not know), it's possible to put a picture of a ruler on-screen and ask "In the image above, what's the largest number you can see without scrolling?" |

Include an opt-out option. Always include an option for people to signify that a question does not apply to them or that none of the suggested options are appropriate. These are typically phrased as variations on "None of the above," "Don't know," or "No Answer," depending on what's appropriate for the question.

Leave space for comments. Although most people won't use them, you should include a space at the end of the survey for people to provide comments about it.

Edit and Order the Questions

The first thing you need to do is to pare down the survey size. One way to maximize the number of responses to a survey is to keep it short. Most people should be able to complete your survey in 20 minutes or less. Surveys that take more than 20 minutes begin feeling like a burden, and respondents have to schedule time to do them. Since reading the instructions takes about 5 minutes and each question takes 30 seconds or so to read and answer, this limits you to about 30 questions total. Keeping a survey to 20 questions leaves you with a safe margin. Besides, as the old game implies, you can find out almost anything about anyone in 20 questions, provided you choose the questions carefully.

Once you've written and culled your questions, it's time to edit and organize them. The question order is as important as the wording. A survey is a dialogue, with every question revealing something to the person taking the survey and providing information to the person receiving the results. Question order should pace, focus, and selectively reveal information.

In some ways, a survey is like a short story. The beginning grabs the readers' attention, drawing them in. As they read the survey, they begin to get an idea of what kind of information the survey is trying to find out. In the middle, big ideas are explored and "twists" on the basic plot are introduced as certain avenues of inquiry are followed. Finally, loose ends are tied up, and the survey ends. Admittedly, even at their best, surveys do not make exciting stories, but writing them with even a small narrative arc can make them more interesting for the participants, which reduces the number of people who drop out due to boredom.

As in a story, you can gradually reveal what the survey is about, not explaining too much up front in order to get people's responses about general topics. Earlier topics may influence people's expectations and thoughts. If your survey is trying to understand how people buy toys online, you may not want to reveal that your survey is about toys until after you've gotten a general picture of their buying behavior.

For example, a survey is trying to understand the relationship between people's food-buying and toy-buying habits. The following two questions are logical ones to pose:

-

What was the total price of groceries you bought last year?

-

How carefully do you track your purchases?

If question A is asked before question B, then people may think B applies only to groceries, which they may track very carefully, but the survey is more interested in people's general purchasing behavior. By asking B before A, the survey collects people's general impressions without constraining their perception of the survey's scope.

A typical survey has the following four parts:

-

An introduction that presents the purpose of the survey, instructions for filling it out, the duration of it, and contact information in case questions arise.

-

A beginning with teaser questions. These questions should be interesting to the person taking the survey, drawing them in. They should not be demographic questions, which are considered boring and, at this early stage, could be construed as intrusive.

-

A middle, where it's a good idea to keep things moving by alternating questions that are likely to be interesting to the respondents with questions that are not. Questions are grouped thematically, such as "General News Reading Behavior," "Online News Reading Behavior," "Quality of News Sources," and "Unmet Needs and Desires."

-

The end, which concludes with all the remaining demographic questions, provides an open-ended field for general response, and reiterates the contact information.

Within this structure, the survey should be flexible. When there isn't a logical progression in a list of answers to a multiple-choice question (best-to-worst, most-to-least, first-to-last, etc.), the list should be randomized whenever possible. This reduces the chances that the order of the answers will affect how people choose. Some online survey software products do this automatically, but it's also possible to create several versions of the survey with answers in a different order and randomly assign people to them when creating invitations.

Write the Instructions

There are two different kinds of instructions in a survey: general instructions and individual question instructions.

The general survey instructions should be brief and straightforward. They should run a paragraph at the longest and contain several pieces of information:

-

That the survey is important. "We want to make vFork a better service for you. Your participation in this survey is very important to us."

-

What it's for. "The survey is to help us understand the needs and desires of the people using vFork."

-

Why people's answers are safe. "All of your answers are confidential and will be used strictly for research. There will be no sales or marketing follow-up because of your participation in this survey."

-

What the reward is. "By completing this survey, you will have our gratitude and a 1 in 100 chance of winning a Palm personal digital assistant."

-

Who is responsible for the survey, if not the company in question. "This survey is being administered for vFork by Adaptive Path LLC."

-

How long the survey is running." This survey will run from July 17, 2003, until July 24, 2003."

-

Who to contact with questions. "If you have any questions or comments about this survey, you may enter them into the form at the bottom of the survey or email them to Mike Kuniavsky at <mikek@adaptivepath.com>." This also personalizes it (the survey is no longer an anonymous form), which tends to increase the response rate.

Question instructions should likewise be simple and straightforward. Most close-ended questions won't need special instructions, but open-ended questions should say exactly what kind of answers you want. Rather than writing

| Warning | Many places, such as most of the United States, have laws governing sweepstakes (which is what a survey offering a "one in X" chance to win something becomes). Sweepstakes require that their rules be clearly posted along with the survey description. You can get most of what you need by copying the rules from another sweepstakes, but you should absolutely have a lawyer look at what you've written before you launch your survey to the public. Likewise, many places have rules about interviewing children. You should make it clear that the survey should be taken by people 13 and older. If your target audience contains a lot of kids, you should consult with a lawyer about how to allow them to take the survey (often this requires written permission from their parents). |

List your favorite Web sites.

the instructions could say

Make a list of the URLs (Web addresses) of sites that you go to often or that you really like. Write up to 10 addresses.

For questions where you want a single answer, but people may feel that any of several options may be adequate, make it clear that they have to select what they feel is the strongest option.

Likert scale grids generally need a couple of sentences of explanation.

The following is a list of features that can be found on vFork and other online fork sites. If you believe that you have used one of these features on vFork, please rate how important the service is to you when buying forks online. If you have never used a feature on vFork please select "Never Used." If you don't know whether you have never used it, select "Don't Know."

You should also make additional instructions visible whenever it's appropriate, such as for error pages or for sections of questions that resemble other sections, but function differently. For example, if a page is reloaded because of an error, the reasons for the reloaded page and any new instructions should be clearly highlighted on the first screen people see after the new page appears.

Lay Out the Report

The report? But we haven't started yet! That's right, lay out the report. One of the best ways to know what questions to ask is to make a list of the answers you want.

The data you collect should be dependent on what analysis you want to perform, what questions you want to answer. You should never ask questions "just in case" (although it's OK to ask exploratory questions for which you don't have a good idea how people will answer).

Your report should begin with your goals and your methods. Writing as if the survey has already been completed, describe why you've run this survey, your goals, and the design of your research. Include information about your estimates of the size of the total population from which you sampled, your sampling method, the size of the sample, the completion rate, and how you analyzed the data. Then write your conclusions. Of course, before you start analyzing your data, you won't know what your real conclusions will be, so these will be your hypotheses, but you will have some idea of what kinds of conclusions you want to have. So write those down.

Sixty-five percent of the people who bought forks in the last month buy forks three times a year or more.

This tells you that you need to collect information about when the last fork was bought and how many times people buy forks a year, and the people who bought forks in the last month need to be large enough for analysis based on it to produce statistically significant results.

Once you've written down your placeholder conclusions, you should make all the tables and graphs you're going to use to back up your conclusions. As the following example shows, the tables should say exactly what variables are being plotted against what other variables and what's being displayed.

| Features | Length of Time on the Web | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 6 Mo. | 6 Mo.–1 Yr. | 1–2 Yrs. | 2 Yrs. | |

| Fork Finder | ||||

| Shopping Wiz | ||||

| Main Catalog | ||||

Because the process of writing the report can affect the content of the survey, make sure you budget enough time to write the report beforehand. That way you can make changes to the survey method or the kind of data you collect.

After you've run your pilot survey, use your report mock-up and run all the pilot data through the same processes you're planning for the real data, making the same tables and drawing conclusions as you would with the real thing. This will help shake out issues with your analysis procedure.

Web Survey Tips

Now you're ready to build the survey on the Web. I won't go into the technical aspects of creating a survey for the Web since the process will depend on your existing systems if you're using a software package that does much of the presentation and tabulation work. However, the basic structure of all Web surveys is the same: an HTML page containing a form and a backend CGI program or email-based script to collect the results. Tabulation is accomplished via a custom program, a statistical program, or for simpler surveys, a spreadsheet.

As of 2002, in addition to a myriad of commercial products, there are several free online survey presentation and tabulation services that, though not as fully featured as a commercial product, address most of the needs of simple survey research.

-

Sparklit (www.sparklit.com)is an ad-based polling service that allows you to ask basic multiple-choice questions and then tabulates the results as simple tables.

-

Zoomerang (www.zoomerang.com)offers a larger set of question types, a selection of premade surveys, and the option for more sophisticated analysis tools for a fee.

-

Survey Monkey (www.surveymonkey.com)similarly offers a larger selection of question types and more survey options.

In addition, there is phpESP (phpesp.sourceforge.net),an Open Source survey construction and tabulation package that runs on Web servers that have the (likewise Open Source) PHP server-side scripting language installed.

There are some things to keep in mind when building any kind of Web-based survey.

Error checking. The backend system can check how people responded. If any are missing or incorrectly filled out (for example, if someone checked a checkbox for a specific choice and "None of the Above"), the page should be reproduced with the incorrectly filled-in responses clearly flagged.

Functionality. Survey pages should be checked like any other page on your site for functioning HTML, even more than usual. The survey page should download quickly and look right on as many browsers, operating systems, screen sizes, and modem speeds as possible. If you expect a segment of your user base to be using AOL or to be behind a firewall, make sure you check the performance with those systems, too. If you use JavaScript in the page, make sure that it works on all browsers and that there's an appropriate error message for people who have JavaScript turned off (or can't interpret JavaScript at all).

Usability. Usability-test the survey just as if it were a new feature. This helps to make sure that everything works and that people's experience of it matches their expectations.

Timing. Since you can keep track of when responses are returned, do so. This will help keep track of what responses arrived within the research period, and it provides another piece of information about the behavior of your user population. If a large group of your respondents claim to be in the eastern standard time zone and their responses arrived between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. EST, you can hypothesize that they were accessing your site from work.

Mortality. Keep track of the people who drop out of the survey. Note at which points they dropped out, and try to draw some conclusions about how they differ based on the answers they completed.

Response rate. Similar to mortality, this is a count of people who were offered to take the survey versus how many actually responded. This is critical information when projecting your analysis to a larger population.

Distinguishing between skipped responses and default responses in Web surveys can be difficult unless forms are set up to anticipate it. Create a difference by making the default option a space character. This doesn't sway people toward selecting a specific option and makes it clear when something is selected (and the space character makes sure that there's someresponse in the file, which makes it easier to process the data and exchange the data). The HTML for a blank pull down menu is

<select name="news_quality> <option value="1> Strongly agree <option value="2> Agree <option value="3> Neither agree nor disagree <option value="4> Disagree <option value="5> Strongly disagree <option selected value=" "> <\select>

For radio buttons, don't define any options as "checked" by default.

<P>What is your gender?<\P> <blockquote> <P> <input type="radio" name="gender" value="M"> Male <br> <input type="radio" name="gender" value="F"> Female </P>

As opposed to

<input type="radio" name="gender" value="F" checked>

Test the Survey

Take every opportunity to pretest each aspect of the study design under whatever testing conditions may be available.

—Earl Babbie, Survey Research Methods, p. 235

A survey can often only be run once. Rerunning a whole survey is almost as expensive as running the survey the first time; surveys shouldn't be changed on the fly. Pretesting the survey (also known as pilot testing) is a critical part of its development and can eliminate a lot of costly mistakes.

A pretest is run just like the real thing, using all the same software, the same recruiting methods, the same data collection methods, and the same analysis methods as the final survey. You should even make a pretest report using your report template, drawing conclusions just as you would with the final data. The difference is in terms of sample size. A pilot sample contains 5–10 responses from people who are, ideally, representative of the group who will be responding to the survey (if you can't get people who match that profile, it's OK to use people who may match only some of the key criteria). Don't tell the participants that it's a pretest. Use the same invitation materials you would use for the regular test, and see if the answers they provide are what you had expected.

| Note | If you have the resources or if this is going to be a particularly involved survey, consider running a prepilot survey, where you present 5–10 people with the survey questions phrased in an open-ended way. If all of their responses fit within the responses you have written in your prepared survey, you can be pretty sure you've covered the appropriate ground. |

Afterwards, or simultaneously, do two or three in-person user tests of the survey, watching people as they take the survey. Keep track of how long it takes them to take it and what problems and questions they have about it. You can also follow up with an email to the pilot participants, asking them to discuss how the survey went, what kinds of problems they had, and so forth.

The Incentive

Unless your survey is extremely short, you should provide an incentive for people to take it. You will want to provide an incentive that's related to the complexity of your survey and the interests of your audience. Knowing your audience is important to picking the right incentive. The incentive for a site for teenagers and one for middle-aged millionaires will have different incentives, but the goal is the same: it's a reward for giving up a portion of their time and personal information. An online gaming information site offered a chance to get one Microsoft XBox in exchange for its visitors' participation in a survey. Ninety-five percent of the people visiting the site took the survey, a proportion that beats many censuses.

The way you present your incentive is important. If you're offering something that's worth $2 for a completed response and your survey takes half an hour to complete, many people may not think that it's worth their time to fill out. However, if you offer a 1 in 100 chance to win something that costs $200, you're likely to get more responses. Although the end costs to you are the same, it's been shown that people would rather gamble with their time for something that's worth more than take a sure thing that's worth less. Why? Who knows.

Fielding the Survey

Fielding a survey is the process of inviting people to take it. It sounds simple, but it's not. Surveys are neither censuses, which attempt to get responses from the entire population, nor questions answered by a haphazard group of people. They attempt to contact a randomly selected, evenly distributed subset of the population in a controlled way.

So before thinking about how to field your survey, it's important to discuss what it means to pick a sample from a population.

| Note | Since a large amount of survey analysis is understanding the uncertainty of the collection method, one of your chief goals in survey design should be to reduce the number of variables that need to be considered and controlled. Everything can influence how people respond to the survey, from who sees the survey to how fast the description page downloads. Thus, as you're creating the survey and the mechanisms for gathering respondents and collecting responses, continually think of ways of reducing the number of unknown variables. |

The Sample and the Sampling Frame

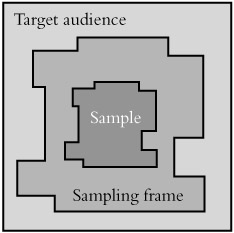

The group of people who fill out your survey is called a sample, but what is it a sample of? It's a randomly chosen subset of the group of people your sampling method can put you in contact with. This group is called the sampling frame (see Figure 11.1). In other words, out of the universe of all of your users, there's a subset your methods allow you to contact and a subset they don't. The subset you can hypothetically contact is your sampling frame; a random selection of people from your sampling frame is your sample.

Figure 11.1: Sample and sampling frame.

Ideally, the sampling frame matches the whole population of people you're interested in. If it doesn't, then your results can be inaccurate and misleading since they will not represent the views of your entire audience. For example, if you field a survey only to the people who have complained about your product, you're not likely to get a good representation of your whole audience's opinion. Likewise, if you talk only to people who have signed up for a mailing list or who have purchased something from your site, you're talking only to a group of people who have expressed an active interest in your product, and those people likely form a minority of all the people who may be interested in what you have to offer.

Sampling frame mismatches can come in all kinds of flavors as well. If a survey is run only on Monday and Tuesday for a ski conditions site that gets the majority of their users on Thursday and Friday, the results will not be representative since the weekend ski audience is likely to be different from the midweek audience. Likewise, just running the survey on Thursday and Friday may miss a key market of hardcore ski enthusiasts. Knowing the composition of your sampling frame is critical to knowing how valid your results are. Unfortunately, there are many, many ways to sample badly and get the wrong sampling frame.

First, define the groups of users you're most interested in. Usage frequency is a good place to start. Are they regular users? (How do you define "regular"? Every day? Every week?) First-time users? Infrequent users?

Now add other characteristics that are important and that can affect the way you recruit people for your survey. Are they people who have bought products from your site? Are they from a specific geographic region? Are they students? People who are thinking of switching from your competitors' products? Power users?

Your survey may end up being the combination of several subgroups (power users and frequent users, European purchasers, and others).

Having decided who your users are, you will have to create a way that will comprehensively invite the people who make up your target audience, without missing or over representing any groups. Each characteristic will create a different method of inviting people and a different set of potential problems in terms of data collection.

For example, say you're interested in the usability problems of frequent users, so you'd like to profile people who use your site all the time. Although it may be interesting to know if there's an observable difference between people who visit often and people who visit and buy your products, you need to stay focused on your target audience choices. So, for example, you decide that your target audience is "users who visit the site at least once a week and who have bought something."

So how do you contact these people? You could use a tracking cookie and ask questions of people whose cookies are less than a week old. But that's dependent on people not having switched machines, deleted their cookies, or changed browsers. What's more, it assumes that you have tracking cookies. It may be easier to randomly invite users and filter out the responses of anyone who doesn't say they visit at least once a week. Moreover, you will need to run your survey for at least a week or in week-long increments, so as not to over represent the visitors who show up on any given day. But is that still guaranteed to target all the users who fit your target profile? No. Some of them may be on vacation; others may skip a week and miss your survey. However, since people do these things randomly, it's unlikely that this will affect your results. There may also be other groups of users—say, people who shop infrequently but buy a lot—who are also important to you, but you're not aware of their existence. Missing these people can really affect your results. So how are you going to know about and contact all these people? You won't and you can't, but you should strive to contact enough people that their responses can make a positive change in your product.

All this is to say that the more you know about your population and their habits, the better you can choose your sampling frame. However, if you know little about your audience, don't panic. Your first survey can be fielded to reveal a lot about your audience's profile, and qualitative research (contextual inquiry, focus groups) can reveal things about their behavior so that subsequent surveys can be more accurately targeted.

Sample Size

So how many people do you invite? Surveys always contain some amount of uncertainty. There always is a possibility of error in a sample since you're not asking every single member of the population the same questions in the same way. The size of the uncertainty can be estimated mathematically, but the amount that's acceptable will have to be decided by you.

Ultimately, surveys depend on the variation in your population. If all of your users are identical, then you need to ask only one of them to understand how all of them would respond. But all of your users aren't identical, so you have to estimate how many to ask based on how varied the population is. This is a classic chicken-and-egg problem: you can't find out how varied your audience is without surveying them, and you can't survey them unless you know how varied they are. Fortunately, it's possible to estimate how many people to invite by assuming that your population has a pretty "standard" variation and then adjusting future surveys if the estimate turns out to be too low (asking too many people is rarely a problem, other than the extra work it involves).

Let's start with the assumption that your entire user population has 10,000 people in it. That means that if you count everyone who has ever used your site or is ever likely to use it (within reason, say, within the next year), you'll get 10,000 people. Now you want to find out how many of them you need to survey in order to be able to get an idea of how all (or the majority) would answer your questions. You'll never get the "real" values unless you survey all 10,000 people, but (without going into the math—that's covered later in this chapter) by asking 300 of them, you can be 95% confident that the answers you get from them will fall in a 10% range ("plus or minus 5%," as they say on TV) of what you'd get if you asked everyone. What does "95% confident" mean? It too is explained later in the chapter, but for now you can read it as "pretty darned confident."

Three hundred people is fine, it's not such a big number, but what if your audience has a million people in it? Thirty thousand is a lot of people to have in a survey. Fortunately, the relationship between the number of people in your population and the number of people you need to talk to is not proportional in that way. The way the math works, you need to sample only 2000, which is significantly easier. So, without consulting a statistician, you can use the following table to estimate the number of people you need in your sample.

| Population | Sample Size |

|---|---|

| | |

| 1000 | 150 |

| 10,000 | 300 |

| 100,000 | 800 |

These numbers are a very rough minimum number of responses necessary for you to be able to extrapolate a survey statistic to the population at large. Statisticians will chastise me for butchering the statistics involved (and, believe me, they are butchered), but the numbers are close enough to make some educated guesses.

To complicate things a bit more, these numbers don't apply to your whole sample size, but to any single group you're going to be studying. If you're going to be segmenting your audience into subgroups (such as by gender or by experience or by region) and doing calculations on the subgroups, then each subgroup needs to be that big. For example, if your product has 10,000 unique users and you're planning to analyze frequent users separately from infrequent users, both sets of data must have at least 300 entries. This means you'll need to have at least 600 responses in your total sample.

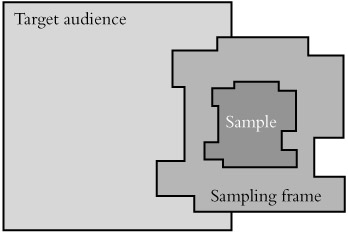

Bias

Sampling bias is the Great Satan of survey research. It's clever, insidious, omnipresent, and impossible to eradicate. It's when the people who you thought would respond—the members of your sampling frame—are not members of the population that you're trying to sample (as illustrated in Figure 11.2). This is very dangerous.

Figure 11.2: Sampling bias.

For a sample to provide useful information about the population as a whole, it needs to resemble that population and their views. If it does not, then certain subgroups or views will be over represented while other groups and views get shortchanged. When the data from a biased survey are tabulated, the results don't describe the population. Since the purpose of a survey is to describe your users, misrepresenting elements of your audience undermines the whole endeavor.

To some extent, you are always going to exclude certain people. Just by fielding your survey on the Web, you are cutting out people who are not on the Web. By writing your survey in English, you are cutting out those who don't read English. The keys are to know whom you are excluding (or misrepresenting) and to make sure that they are not members of your target audience and that you do not include them in your analysis.

One of the most common and important kinds of bias is nonresponder bias. Some number of people will always ignore your invitation, but if there's a pattern to those who do, it's bias. If your survey is repelling a certain group, then they'll never be represented in your research. For example, if you're surveying people about their time use, and your survey takes 45 minutes to complete, you may be missing the most important segment of your market simply because they don't have time to fill out your survey. There are many other different kinds of nonresponder bias.

-

Timing bias. Does the time you invited people affect the way they answered? If you ask people about how much they enjoy shopping for gifts on the day before Christmas, you may get a different response than if you ask at a time when people aren't frantically grabbing toys off the shelf.

-

Duration bias. Some behavior is cyclical: it consistently peaks during a certain part of the day or week or month. If your target audience consists of commodities traders and you run your survey from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. when most traders are too busy to fill out surveys, you will likely miss a large portion of your audience.

-

Invitation bias. How did you invite people to participate in the survey? The places, times, incentive, and wording all affect who is going to respond. If you're trying to invite skateboarders and you begin your invitation with "Dear Sir or Madam, you are cordially invited to . . ." you likely lose much of your audience (unless the invitation is obviously ironic). If you offer T-shirts as an incentive to senior managers, you're not likely to get a representative group.

-

Self-selection. A special kind of invitation bias and a common mistake in Web surveys is the practice of letting people choose whether they want to participate in a survey without explicitly inviting them. "Click here to take our survey!" is often how this is presented. Who is going to take that survey? Why will they take it? In an opt-in situation like this, you have no idea who the people who aren't clicking on the link are. They could be the same kind of people who click on the link, but it's doubtful. Opt-in surveys tend to attract people who have extreme opinions and specialized interests, which is rarely the only group that you want to attract. It's better to have people have to opt out of a survey than opt in. That way you know that a random distribution saw the invitation, how many people were invited, and how many chose not to take it.

-

Presentation bias. The way you present the survey, the survey's look and feel, also determines who feels interested in answering it. Technologically, if you use JavaScript to perform a certain key function and a portion of your key population has JavaScript turned off, they won't be able to take your survey. Esthetically, if you present the survey with a bunch of cute cartoon characters around it, businesspeople may be reticent to take it (conversely, if you present a plain black-and-white screen full of text to a group of teenagers, they may think it's too boring to pay attention to). The visual polish of surveys should match that of the sites they're being linked from. If a slick site links to a survey that is stylistically drastically different, it may cause confusion (and, if the shift is too harsh, it may even affect people's perception of the site brand).

-

Expectation bias. People have expectations of what a survey is going to be about and why they should take it. If those expectations are not met during the course of taking it, they may abandon it. In a pretest of a survey, one user said "Oh, I thought that this was going to be about me and it's asking all these questions about how I change the oil. I don't care about that."

The art of survey design is in tracking response rates to minimize and understand all the preceding factors while maximizing participation. Tabulating results and drawing conclusions are pretty straightforward in comparison. Typical online survey response rates vary between 20% and 40% (which means that between 20% and 40% of the people who are offered to take the survey take it and finish it). Much less than 20% and the results of a survey are highly dubious. As Joshua Grossnickle, co-author of The Handbook of Online Marketing Research, says, "a survey with a 1% response rate is worthless data." Testing your survey and understanding the implications of your design in terms of the groups that it is excluding are key ways of minimizing the amount of bias.

Invitation

After bias reduction, the next task to consider is how to randomize your sample. Finding a truly random sample can be tough and depends on how you invite people. There are a number of common ways of inviting people to take your survey, and each method has its own benefits and carries its own problems.

Invitation Link

This is the easiest but least accurate survey invitation method. It consists of a link from a key page (generally the home page) inviting people to participate in a survey. Its benefits are that it's cheap and unobtrusive, but it suffers heavily from self-selection bias. There's no guarantee that a random selection of users to the site sees it, and there's no attempt to distribute the invitation among visitors, so the people who take it are likely to be people who want to communicate something about the site. These groups are likely to be experienced users who have strong opinions. Their views are useful, but are rarely representative of the typical user's views.

If you do use a front-door invitation link, keep track of all the unique visitors to that page and compare it to the number of people who responded. This will give you some idea of how many have seen the invitation versus how many filled out the survey. If the response rate is small (say, 5% of the number of people who have seen the site), then there's a high chance that the responses are not representative of your audience. The survey may still produce useful information, but it's unlikely that the conclusions can be extrapolated to the population at large.

If you have a list of known users, you can select a random subset of them and invite them to take the survey. Such an invitation list won't reach users who aren't in your database (and therefore haven't used the services of your site that get them into your database), and it won't reach people who have opted out of having email sent to them, but it will let you contact people who almost certainly use your site. More important, it lets you issue explicit invitations so that you know that all potential users were exposed to the same invitation (thus reducing the problems of self-selection), and it lets you track exactly how many invitations resulted in responses.

| Warning | When using tracking identifiers, make it clear that the survey software possesses this capability so that respondents who expect the survey to be anonymous know that it's not. Also make it clear that even though it's not anonymous, responses will still be confidential. |

There are two basic kinds of email survey invitation: one that's just an invitation to visit a Web-based survey and one that results in an email-based survey. Although email-based surveys can reach a wider group of people, they involve more work on the data collection side since the responses have to be parsed (either by hand or with software).Web-based surveys are generally preferred.

Ideally, each email survey invitation will have a unique identifier that will allow you to track which and how many people responded.

Interruption

An interruption invitation works by inviting random users to take a survey as they are visiting your site. Every user has an equal chance of being invited (either every time they visit the site or once per user), and the invitation interrupts their experience of your site such that they have to actively accept or decline the invitation to continue using the site. This tells you exactly how many people were invited, ensures that they were all equally aware of the survey, and guarantees that they are a random sample of all users.

Random interruptions can be done either by probability or systemically. Sampling by probability involves choosing visitors according to a probability that will make the total amount of visitors that meet that probability roughly equal to the expected number of responses. In practice, this generally involves picking a random number for each visitor; if the random number matches a predetermined "magic number," then the person is invited to take the survey. Otherwise, they experience the site normally, never knowing that a survey is under way for others. So if you have determined that you need 1000 responses for a week-long survey and the site gets about 100,000 unique visitors per week, then each visitor during that week should have a 1 in 100 probability of being invited to take the survey.

A useful way of creating a consistent probability sample is to include a piece of code on every page. This code snippet performs the necessary calculations about whether the current visitor should be offered the survey and leaves a cookie in his or her browser so that the visitor isn't considered for invitation more than once per survey (unless, of course, the survey is measuring behavior per visit, rather than per visitor, but those types of surveys are considerably rarer).

Here is a piece of JavaScript written by Joshua Grossnickle and Oliver Raskin, authors of The Handbook of Online Marketing Research. It works in most situations (though, of course, not if the recipient's browser has JavaScript turned off).

<script language="javascript"> //<!— //the variables sLocation and sRate //are set to the location of your survey and //the desired sampling rate var sLocation="http://www.adaptivepath.com/survey.html"; var sRate = 15; var cookieName = "SurveyCookie"; var cookieValue = getCookie(cookieName); if (cookieValue == null) { setCookie(cookieName, "Sampled"); var sampled = Math.random(); if (sampled < sRate) { window.open(sLocation,'sWindow','scrollbars,resizable'); } } function getCookie(Name) { var search = Name + "="; if (document.cookie.length > 0) { offset = document.cookie.indexOf(search); if (offset != -1) { offset += search.length; end = document.cookie.indexOf(";",offset); if (end == -1); end = document.cookie.length; return unescape(document.cookie.substring(offset,end)); } } } function setCookie(name,value,expire,domainname) { document.cookie = name + "=" + escape(value) + ((expire == null) ? "" : ("; expires=" + expire.toGMTString()) + "; path=/" } //—> </script> In order to accurately measure all visitors, not just those who visit the home-page, the code needs to be inserted into every page that someone can get to by typing in a URL. This is easiest with dynamically generated sites, or sites that include a uniform navigation header (in which case the code can be inserted as part of the header), but even sites that are "flat," made with plain HTML, should still have it inserted at all the likely entry points into a site.

Systemic interruptions are sometimes simpler. A systemic sample works by inviting every nth visitor. In our example, this would equate to picking a random number between 1 and 100 and then taking every 100th visitor after that person until 1000 visitors have been invited. This is more of a traditional paper survey technique, where it has the advantage of being simpler to implement, but it's not as flexible.

Telephone, In-Person, and Standard Mail Surveys

Traditional survey techniques such as telephone, in-person, and paper mailed surveys are beyond the scope of this book, but they should not be forgotten because they're the most effective ways to get a truly random sample of the population. These are the typical survey techniques used by political and market research. One typical tool is the random phone call: a machine randomly dials phone numbers within a certain area code and telephone exchange until someone answers, then a person takes over and begins reading a telephone survey script. However, users of a specific software product or visitors to a certain Web site are likely harder to find by randomly dialing phone numbers than people who belong to a certain political party or who buy a certain product, so the technique isn't as efficient for finding users. Although collecting data in person seems to defy the global nature of the Internet, if your audience is easily accessible—such as for a site that's serving the teachers in a local school district—then the flexibility and information-gathering potential of an in-person survey is hard to beat. These methods are generally more time consuming and expensive than Web-based surveys, but they should not be forgotten just because they're not digital.

| Warning | The world abounds with bad survey research that's bandied about just because it contains numbers. Do not be deceived by numbers, and do not try to deceive with numbers. Just because there are numbers does not mean that a rigorous process has been used to arrive at those numbers. |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 144