Analysis: YNM S Social Oracles

Analysis: YNM'S Social Oracles

The data indicates that social oracles are effective advertising tools, and the primary aim of this chapter is to understand why. We take a cognitive approach to answering this question based on the theoretical framework of distributed cognition (Hutchins, 1995a, 1995b). Distributed cognition researchers view cognition as more than just a process inside the heads of individuals. Rather, cognition is a process that can extend beyond the individual to incorporate a wide distribution of resources. Thus, a collection of people and technology interacting to perform a task - such as the users that interact through the social oracles - qualifies as a cognitive system. Other examples of supra-individual cognitive systems, which distributed cognition researchers have studied include: air traffic control (Halverson, 1995); aviation (Hutchins, 1995b; Hutchins & Palen, 1998); computer-mediated work (Rogers, 1994); fishing (Hazlehurst, 1994); guitar song imitation (Flor & Holder, 1996); helicopter piloting (Holder, 1999); large ship navigation (Hutchins, 1991); puzzle solving (Zhang & Norman, 1994); computer programming pairs (Flor, 1998); customer-centered businesses (Flor & Maglio, 1997); and video-game playing (Kirsh & Maglio, 1994).

Distributed cognition researchers employ a variety of techniques including field studies, experiments, and computational models, as a means of analyzing cognitive phenomenon conceived as a distributed process. For studying businesses as cognitive systems, Flor and Maglio (2004) have developed a representational analysis technique that combines physical symbol system concepts (Simon, 1981) with distributed cognition principles. Briefly, it is an inductive method where one first charts the movement of a symbolic state (information) across the individuals and technologies (collectively 'agents') that participate in an activity. By abstracting the agents and information in the chart (also known as an information activity map) one can induce the general processes underlying the observed information activity (see also Appendix C for a primer on representational analysis).

Analysis of Oracle 1

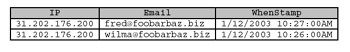

To uncover the social process the Compatibility Game is adapted from, we start by analyzing the information activity in an actual use of the game. Each time a customer, (C), sends a compatibility report to a friend, (F), that customer's IP address is logged, along with the recipient's e-mail address and the time the report was sent. Figure 1-4 depicts a portion of this database log for a user with a specific IP address of 31.202.176.200. The log indicates that this user played the Compatibility Game twice on 1/12/2003 and e-mailed results to two friends .

Figure 1-4: Database entry for the Compatibility Game

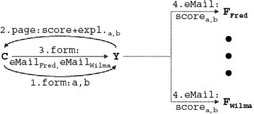

When the user played the game, he or she entered two names into the game's form (1. form: a, b). The game then returned a page with a compatibility report - both scores and explanations - for a and b (2. page: score+expl. a,b ). Next , the user entered e-mail addresses for two friends (3. form: eMail Fred , eMail Wilma ). Finally, YNM sent an e-mail containing just the scores to these friends (4. eMail: score a, b ). Figure 1-5 depicts the information activity map for this specific user.

Figure 1-5: Specific information activity map for the Compatibility Game

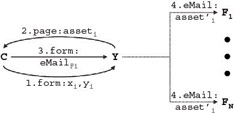

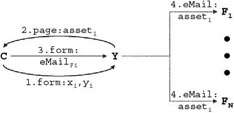

Figure 1-6 is a generalization of the information activity map in Figure 1-5. A customer (C), enters names (1. form: x i , y i ) into the social oracle, which then returns a social asset (2. page: asset i ) - social information that is of interest or value to members of a given community and that C naturally wants to share with friends and associates . C uses YNM to e-mail this social asset (3. form: eMail Fi ) to one or more friends (F 1 F N ). Recall that the friend does not receive the entire asset, just a portion, or derivative, of the asset (4. email: asset' i ).

Figure 1-6: General information activity map for the Compatibility Game

To uncover the social process underlying the Compatibility Game, first realize that the customer does not know that YNM is just e-mailing the scores to a friend. The customer believes that YNM is sending the entire report; both scores and explanations (Figure 1-7).

Figure 1-7: What the customer believes is happening (asseti, vs: asseti')

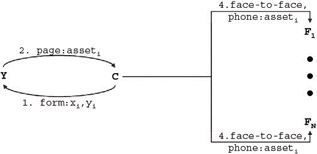

From C's point of view, YNM is simply relaying the same information to C's friends (F i ) that C would have relayed on his or her own. The difference is that YNM uses e-mail as a distribution medium, whereas C would have communicated the information either face- to-face or over the phone, to name just a few of the 'offline' media typically used by C. Figure 1-8 depicts the information activity map if C were to relay the social asset, offline, to his or her friends.

Figure 1-8: Customer conveying the social asset 'offline'

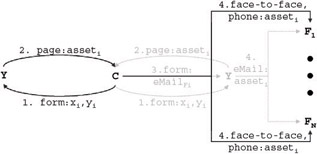

If we superimpose the maps for Figure 1-7 and Figure 1-8 at C (Figure 1-9), it is apparent that both activities accomplish the same function, namely the delivery of a social asset to a customer's friends.

Figure 1-9: Superimposing the maps for Figure 7 (lightgray) and Figure 8 at C

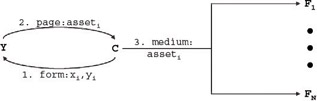

The difference is in the medium used to deliver the asset. In the offline process the asset is distributed face-to-face or via a telephone, while in the online process the asset is delivered by YNM via e-mail. Figure 1-10 depicts a generalization of the information activity maps for both processes.

Figure 1-10: Information activity map generalized across media

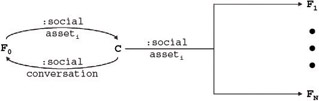

Still, the social process underlying the Compatibility Game is not readily apparent. To uncover this process, we swap in a person for technology. Specifically, by substituting an arbitrary friend of the customer for YNM (F for Y), and replacing the social information that C types into YNM with social conversation between C and the F ( social conversation for x i , y i ), the underlying social process becomes more explicit - the Compatibility Game is a kind of technology-mediated gossiping . Figure 1-11 depicts these substitutions.

Figure 1-11: Compatibility game as gossiping process

In short, the Compatibility Game is based on the rather mundane social practice of gossiping. However, instead of two people creating the gossip, the user interacting with the social oracle generates the gossip. Thus, the Compatibility Game is a kind of technology-mediated gossiping. Next we analyze the social processes underlying the Love Detective.

Analysis of the Social Process Underlying the Love Detective

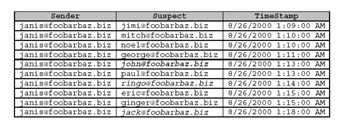

Each time a user plays the Love Detective, his or her e-mail address gets stored in a database table along with the e-mail addresses of the persons they enter as suspects . Figure 1-12 depicts a part of the table for a user (Janis) who was trying to determine which of 10 acquaintances liked her.

Figure 1-12: 1st generation game user (suspects that responded are italicized)

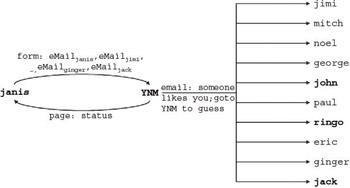

Figure 1-13 depicts the information activity map based on this data. As the order of the information exchanged is straightforward, information sequencing numbers are omitted from the map.

Figure 1-13: Information activity map for a 1st generation user of the Love Detective (suspects that responded are bolded)

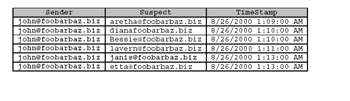

Three users returned to YNM to play the Love Detective in order to find out who sent them the message. Figure 1-14 depicts the database table after one of these users (John) finished playing. Note that he correctly guessed Janis as the original sender.

Figure 1-14: Activity from one of the suspects (correct guess in bold)

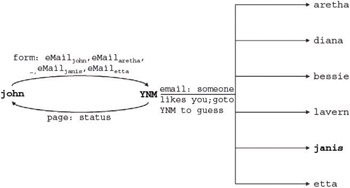

Figure 1-15 depicts the information activity map for this suspect using the Love Detective.

Figure 1-15: Information activity for a suspect (correct guess in bold)

The information activity maps show that the Love Detective is an effective advertising mechanism, because both users and suspects typically enter multiple e-mail addresses to determine who likes them. In turn , for each e-mail address entered, the Love Detective sends a message informing the target recipient that someone likes him or her, but he or she must visit YNM and play the Love Detective to find out who it is.

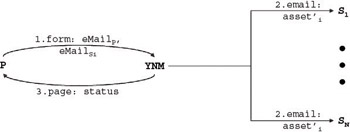

Figure 1-16 depicts the more general situation. A person (P) enters his or her e-mail address (email P ) along with the email addresses (email Si ) of one or more suspects (S i ) - individuals whom the person 'suspects' likes him or her. The suspects receive an e-mail containing potentially valuable information (email: asset' i ), namely a message that someone likes them. However, the information is incomplete and does not specify who. The social oracle returns whether or not there is a mutual interest (page: status).

Figure 1-16: General information activity map for a person playing the Love Detective

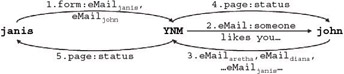

To understand the social process underlying the information activity, let us focus on just the activity between the original sender (Janis) and the person who guessed correctly (John). Figure 1-17 superimposes the maps for Janis (Figure 1-13) and John (Figure 1-15) at the YNM node.

Figure 1-17: Information activity map for Janis and John

We first generalize the agents in the map: Janis as Person , and John as Suspect . When the person and suspect enter e-mail addresses, they are effectively expressing the proposition person likes suspect . However, when YNM sends an e-mail to the suspect, it does not specify the person. The proposition expressed is of the form: someone likes suspect . We next change the labels in the information activity map to represent the propositional content of the information exchanged. The resulting map (Figure 1-18) depicts a person using technology (YNM) to 'ask' another person (the suspect) if there is a mutual interest, by having suspect guess various names (Name i ).

Figure 1-18: Information activity map with player, suspect and information generalized

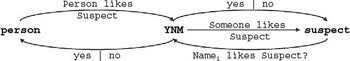

Finally, if we substitute the technology (YNM) with a person (Friend) we can better see the social process that the Love Detective is based on (Figure 1-19) - a hypothetical social process where one person asks a friend to find out if another person, the suspect, likes him or her.

Figure 1-19: Information activity map with a friend substituted for YNM

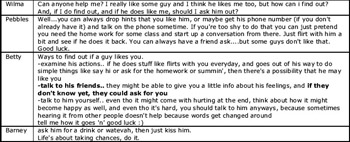

Further evidence for the existence of this hypothetical social process comes from YNM's users. Figure 1-20 is a transcript of a thread in which a user (Wilma) asks how she can 'find out' if 'some guy' likes her. Three users reply (Pebbles, Betty, and Barney) with different opinions . Each opinion describes one or more social processes for finding out if a suspect likes a person. Betty's opinion, in particular, includes a description of a social process similar to - 'talk to his friends if they don't know they could ask for you.'

Figure 1-20: Descriptions of various social processes for finding out if a suspect likes a person

To summarize, the Love Detective is based on a common social process where a person has a friend ask a suspect if he or she likes the person. However, when a person uses the Love Detective, it substitutes for the friend asking the suspect. Thus, like the Compatibility Game, the Love Detective is a technology-mediated version of an ordinary social process. However, through technology mediation these social processes somehow become advertising tools.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 164