Hypotheses Development

As indicated earlier, innovativeness can be conceptualized at four levels of generality. These four conceptualizations of innovativeness can be represented in a simple model (Figure 15-1) showing their hierarchical relationships from general to more specific: global innovativeness marketplace innovativeness domain specific innovativeness time-of-adoption. The broadest and most general level can be termed global innovativeness . This can be described as a personality trait that explains and predicts how people react to new and different things, ranging from rejection to avidly seeking novelty. Global innovativeness appears in several larger personality schemas. For example, Jackson's (1976) personality theory contains 'innovation' as one of twenty personality dimensions along with conformity , risk taking, tolerance, and other global traits. The Five-Factor Model of Personality (Costa and McCrae 1992) contains a trait called 'openness to experience' that has been described as how willing people are to make adjustments in notions and activities in accordance with new ideas or situations (Popkins 1998). Costa and McCrae (1992) characterize 'openness' as curiosity and a motivation toward learning. In these schemas, personality is described by the effects and interactions of a limited number of abstract concepts that summarize consistent individual differences. Thus, global innovativeness may influence many human behaviors, including reaction to new marketplace phenomena, such as online buying.

Less abstract and more specific than global innovativeness is a concept we can call marketplace innovativeness . This term is meant to refer to what most marketers mean when they use the terms 'consumer innovativeness' or 'consumer innovators.' The famous American Tastemakers (1959) reports described 'a leadership elite' of highly mobile and cosmopolitan buyers , who adopted new products quickly and influenced others to also do so. More recently, a positive reaction to new and different products is also proposed by the VALS psychographic segmentation typology , which explicitly contains a category of people termed 'innovators' (SRI-BI, 2003). Consumer behavior texts describe consumer innovators as 'venturesome risk takers' (Hawkins, Best, and Coney, 1998, p. 255) or as especially knowledgeable and influential consumers (Peter and Olsen, 1999, p. 388). Thus, we can describe a type of innovativeness at a less global (or more specific) level of conceptualization than that proposed by personality psychology.

Most consumer and marketing researchers recognize, however, that consumer innovativeness can be studied at an even more specific level of abstraction than marketplace innovativeness. This is the concept of domain specific innovativeness (Goldsmith and Hofacker, 1991). While it is true that some consumers seem to be innovative with regard to many product categories, consumer innovativeness chiefly manifests itself as eagerness to buy new products within specific product categories or domains. Fashion innovators, car buffs, and techno- geeks , for example, will be highly knowledgeable and be opinion leaders within their domains of interest. They also will be heavy users of and relatively price insensitive for their chosen product domain, but their innovative behavior will only overlap with related product categories and will not characterize all their marketplace behavior. Moreover, innovators in a product domain do not share demographics and lifestyles with innovators in other product categories.

The most specific and concrete level at which innovativeness can be conceptualized is the actual behavior of the innovators described by Rogers' (1995) time-of-adoption criterion, whereby degree of innovativeness is indicated by the timing of new product trial (innovators early/laggards late). Measurement of this construct is provided by the time elapsed since new product introduction to individual adoption. In contrast, the other personality concepts of innovativeness are measured by self-report, as are almost all other unobservable, hypothetical, latent constructs. The model also proposes that the effects of each level of innovativeness are mediated by the influence of innovativeness at the subsequent level. Goldsmith et al. (1995) verified that domain-specific innovativeness mediated the link between global innovativeness and purchase (time-of- adoption) of new products in two product categories, clothing and consumer electronics.

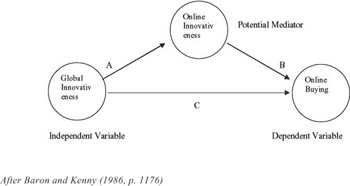

This study assesses the relationships between global innovativeness and domain- specific innovativeness (online innovativeness) with online buying (Figure 15-2). Four hypotheses were tested :

Figure 15-2: A model of the relationships between global and domain specific innovativeness with online buying

After Baron and Kenny (1986, p. 1176)

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 164