5.2 Consumer Power and the Internet

|

5.2 Consumer Power and the Internet

David Gagnon, Susan Lee, Fernando Ramirez, Siva Ravikumar, Jessica Santiago, and Telmo Valido, under the direction of Professor Glen Urban

Although the Internet has not revolutionized the way consumers shop, it has brought more subtle yet equally important management implications. Among these implications is the marketing influence which consumers and suppliers have as a result of the Internet.

On the consumer side, customers have greater bargaining power through increased access to timely and accurate information about their product of interest. On the supply side, marketing automation technology allows targeted promotion and differential pricing. The two forces are generally opposing. Marketing automation supports push marketing and price discrimination, while customer power prevents manufacturers from practicing push marketing.

This paper explores three industries in depth—travel, new automobiles, and health care. For each industry, we examined the pre- and post-Internet industry structures, looked for changes in customer power, and analyzed the strategic responses by firms. From this, we infer which strategies companies should use to balance the forces between increased customer power and increased automation. On the one extreme is pure trust, or advocacy marketing, which entails full, honest information exchange with customers who are regarded as a community. On the other extreme is pure push marketing, which aims to isolate customers and extract the maximum surplus from each customer.

To understand the historical context of the shift in consumer power and its implications for the science of marketing, we look to Douglas McGregor and his impact on the science of management. As noted in chapter 4, in 1957 McGregor posed a new view of what motivates employees. The traditional view, Theory X, held that employees dislike work, avoid responsibility, and prefer to be told what to do. In contrast, McGregor proposed Theory Y, that employees are creative, willing to exercise self-direction and accept responsibility. Theory Y provided a new view of employees as empowered employees, and it led to innovations such as participatory management. Similarly, Theory Y can be applied to marketing. Theory Y marketing provides a view of empowered customers and leads to trust-based marketing. Under trust-based marketing, consumers are seen as imaginative and capable of making decisions. Rather than using one-sided advertisements to push products, companies following trust-based marketing principles provide unbiased information to consumers that helps the consumers make their own decisions.

One element in which all industries seem to be most equally affected by the Internet is in the expansion of the market structure to accommodate new entrants with a prominent online presence. The automotive industry, for example, has seen a massive proliferation of third-party infomediaries and buying services. These companies place themselves between the consumer and the dealer, providing a wealth of resources for the consumer to access, and often generating sales leads that can then be sold to dealerships. In the travel industry, online travel agencies have emerged to enable the consumer to conduct his or her own research and book travel arrangements. This growth has come largely at the expense of independent travel agents, who now find a customer base that is willing to perform the services traditionally managed by the travel agent. The healthcare industry has given rise to online health "super sites" that aim to provide consumers with access to health information previously accessible only to physicians. While the access to prescription medication is still in the control of licensed physicians, the process to determine which drug is most appropriate for a patient can be influenced by an educated patient. This new consumer power has an indirect effect in the pharmaceutical sales process.

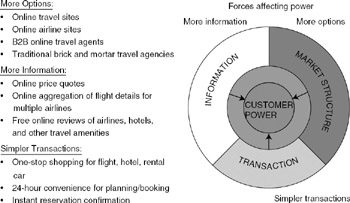

Our research indicates that customer power in this Internet era is largely dictated by three factors: more options, more information, and simpler transactions.

More Options: Does the Internet create new purchase and distribution channels, or is it merely a resource for additional information? Industries that have accommodated the Internet as another option to purchase the product typically provide consumers with a greater degree of power.

More Information: How quickly and easily can consumers obtain timely and valuable information regarding the price, availability, and specifications of available products? The value of this information is enhanced when the consumer has online tools to make direct comparisons between the relevant choices.

Simpler Transactions: Simpler transactions translate into greater consumer power. The Internet empowers customers by facilitating transactions that are easier to evaluate and/or more convenient to execute. Conversely, complicated transactions like those that involve negotiating a final price, customizing an order, or bundling associated products/services tend to mitigate a consumer's power by raising the level of complexity in favor of the retailer.

While we have tried to separate these categories into unique entities, significant overlap often exists, and the three components are highly interdependent. The effect of any one of these components on the total consumer power is a function of the other two components, which becomes obvious in our industry analysis.

The nature of consumer usage varies widely across the three industries we studied in depth. In the automotive industry, the Internet is primarily still a research tool. Over 60 percent of new vehicle shoppers access vehicle information on the Internet before making a purchase, but only about 6 percent employ online purchasing services. In the travel industry, the Internet is a purchase tool that reduces the need for travel agents. Over 35 percent of leisure travelers use the Internet for research and 13 percent of all travel bookings are purchased online. The healthcare industry is more difficult to measure along these dimensions, but over 50 percent of the total active online adult population in the United States are "e-health consumers," meaning that there are approximately 46 million Americans who actively use the Internet to research personal health issues.

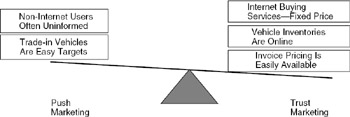

Our breakdown of the factors indicating which strategy (push marketing, full trust or partial trust) is most likely to be successful is summarized below in the weights-and-balance scale analogy.

At one extreme is the pure push business model, which involves virtually no trust. In a push-based business model, a company tries to manipulate customers into buying products and services. The goal is to get as many sales as possible, especially sales of high-margin items. Alluring, flashy ads create hype that drives sales—advertising and marketing emphasize form over substance. Fulfillment and after-sale support are minimal and very cost-oriented. Under the push business model, the goal is to get the next sale, rather than the sale after that.

In the middle is a business model based on partial trust. The company's sales strategy is one that honestly tries to match customers to the products offered by that company. Such a company offers extensive and honest information about its own products, although it will not necessarily provide any useful comparisons to competing products. A partially trust-based company has a value-based pricing strategy so that customers know that they are getting what they pay for. Because trust is one element of such a business model, companies in this middle category will have adequate fulfillment and support services that deliver the promised value to the customer (e.g., good quality products, adequate returns processes, and service guarantees). A partially trust-based company worries about customer retention, but may try to retain customers whose needs are no longer met by that company.

A fully trust-based business model seeks to create customers who trust the company to act on their behalf at all times. Sales, marketing, fulfillment, and support all work together to under-promise and overdeliver. In seeking to unconditionally serve and satisfy customers, a fully trust-based business will actually occasionally act against its own short-term interests (e.g., recommending a competitor's product or covering the cost of some extreme level of service). Because a trustbased company tries to build customers for life, these companies strive to create reputations for impeccable honesty. Although a fully trustbased business can lose customers (whose needs or circumstances change), the quality of the experience means that even ex-customers become delegates of that company's marketing department.

The most significant implication of this model is that the full trust strategy requires a more desirable market presence. This strategy is most successful for companies with the best products and an educated consumer base. These factors also tend to be more stable in the long run, which is another advantage of being on this side of the scale. An educated consumer is able to better validate any corporate claims of product performance, and thus one would expect this customer to be more receptive to the notion of an advocacy relationship with the supplier.

Push marketing, however, is successful in that companies are able to respond to information-enabling technology (such as the Internet) more quickly than consumers can. Therefore, companies can use marketing automation tools to capitalize on consumers that are not yet fully informed about the product/service features. These customers, in the absence of specific information, are more likely to emphasize how much of a deal they believe they are being offered. Since the seller often easily manipulates these perceptions of value, push marketing has the potential to be most effective in the short-term aftermath of new technology introduction. Eventually, consumers will gain access to the information they need to make better judgments, and the seller's marketing automation efforts will be offset by consumer knowledge.

Table 5.2.1 summarizes the impact that the Internet has had on the travel, automotive, and healthcare industries, as well as how those industries have reacted to the changes that the Internet has catalyzed.

| Industry | Evidence of customer usage | Change in industry structure and leadership | Evidence of consumer power | Corporate response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| | ||||

| Travel | >35% of leisure travelers use the Net for research. Over 50% of all airline tickets are sold via the Internet. | Consumers can research and purchase their travel without an agent, diminishing the role of travel agents. | Airlines discontinued commissions to agents. Over 2,000 brick and mortar travel agents have gone out of business. | Travel agents are trying to reposition themselves as personalized service providers. |

| Auto | >60% of new car buyers use the Net for research; 6% use Internet buying services. | Prominent emergence of third-party information and selling services. Dealer network still intact. | Online purchase transactions using an Internet buying service save an average of $450 per vehicle over the traditional buying processes—a savings of about 1.2% | Dealers purchase customer leads generated by Internet buying services. Many dealers offer sophisticated Internet buying tools directly. |

| Health Care | >50% of adults online conduct research via the Internet. | Comprehensive research sites on the Net empower consumers to research their health needs. | Customers select HMOs, research illnesses online, ask doctors for specific products. | Pharmaceutical manufacturers market directly to consumers, encouraging them to ask their physicians about specific products. |

Air Travel Industry

Industry Structure

Five years ago, 75–80 percent of all travel was booked through agencies. Today, billions of dollars of travel are booked online, which has changed the structure of the industry enormously. The Internet has created a vast repository of information as well as extensive marketing and service opportunities. This has led to the birth of large companies like Orbitz.com, which are now considered by airlines to belong to the same category as American Express.

Jeff Katz, CEO of Orbitz.com, believes that travel is one of the few industries that has truly succeeded in taking advantage of the Internet's resources, and in this particular case, "the Internet has increased consumer's power by 100 percent."

NFO Plog Research's The 2001 American Traveler Survey documents the tremendous effect the Internet has had on the trip planning and booking practices of the overall population of travelers between 1999 and 2001. According to the survey, fewer leisure travelers now use travel agents when planning their vacations: 28 percent, down from 33 percent two years ago. During the same period, usage of the Internet has grown by half. Today, 36 percent of leisure travelers use the Internet to gather travel information, up from 24 percent in 1999. Among heavy leisure air travelers (those taking three or more trips a year), 63 percent report using the Internet for research.

Among online air travelers—defined as air travelers who have an email address—the switch is even more dramatic. Ninety-three percent of the online leisure travelers use the Internet as an information source, up from 57 percent just two years ago. The portion of online business air travelers who consult travel agents has dropped 17 percent since 1999, when 59 percent relied on agents as an information source.

Perhaps the more important question is how the Internet has changed travelers' booking practices. According to the survey, agents continue to see an erosion of market share. Currently, 23 percent of business travelers surveyed typically book through agents, down from 33 percent a year ago. One in ten business travelers now typically book through the Internet, up from 7 percent a year ago. On the other hand, 12 percent of leisure travelers say they typically purchase travel online, up from 9 percent a year ago. The percentage of leisure travelers booking their vacation through an agent dropped from 22 percent a year ago to 18 percent.

Although 87 percent of travel is still booked through traditional travel agents and direct-to-supplier venues, the Internet has enabled a new way of travel planning and has increased the leverage that consumers hold over the traditional travel industry players. As a result, over 2,000 independent travel agents have gone out of business in the past few years.

Evidence of Power

With the Internet, customers have more leverage when making decisions about their travel plans. Figure 5.2.1 shows ways in which the Internet has strengthened consumer power in the travel sector.

Figure 5.2.1: Forces affecting power in the travel industry.

Before the Internet, small businesses had to rely on travel agents for their business travel needs, paying a combination of management and transaction fees. If they spent less than $10 million a year on travel, suppliers would not offer them discounted fares. Furthermore, smallsized businesses typically did not have dedicated travel managers to keep track of travel expenses. With the advent of B2B online travel agents that target small and midsize companies—such as GetThere.com, Yatra.net, Delta's MYOBTravel.com, and Continental's RewardOne program—these smaller businesses can now have more control than ever over one of their biggest expenses. The B2B online agencies not only provide standard travel management tools, such as customer profiles and real-time tracking reports, but they also aggregate purchasing power of multiple customers to negotiate deals with suppliers. As competition heats up in this historically underserved B2B travel market, suppliers are providing additional incentives for these small businesses to book directly through them. For example, MYOBTravel customers receive a discount on the first, fifth, and 10th bookings through the site, representing 10 percent, 20 percent, and 30 percent off the published fares, respectively.

For most consumers, a key attraction of the Internet is the ability to save money by bargain shopping. Having price quotes available online allows consumers to price-shop when it comes to travel planning. Travel sites let consumers go beyond the price quotes from a travel agent and instead explore thousands of possible flights almost instantly. What's more, the cost of obtaining information is virtually zero for consumers with Internet access. Finally, the abundance of online information provides consumers with reviews on airlines, hotels, and other travel amenities that they may not have had access to in the past. Tourist information sites provide consumers with destination information on restaurants, sightseeing tours, and tickets to local events.

With the presence of online travel sites, consumers now have the ability to plan their travel any time, day or night. More travel sites are offering one-stop shopping. Through a few clicks, a consumer can do everything from purchasing airline tickets to shopping for concert tickets to renting a car.

Strategic Response by Industry

In response to emerging customer power, some industry players in the travel industry have decided to further empower consumers with a straightforward business model to build trust and loyalty; others have chosen to use the Internet as a tool to target different market segments. Traditional agents are going back to basics.

Southwest Airlines' Internet strategy is apparent throughout its website—direct and simple. No matter what the route is, the website offers nine standard fares (e.g., Refundable, Child, Senior Citizen, Roundtrip Fare Mon–Fri 6 AM–6:59 PM, Discount, etc.). Southwest also lets customers cancel reservations online or apply funds from a previously unused trip to a new purchase. According to Nielsen//NetRatings and Harris Interactive, Southwest Airlines is the top-ranked online travel site for customer satisfaction. The rankings for customer satisfaction include factors such as site ease-of-use, information availability, flight options, pricing, duration of shopping experience, and customer service.

While Southwest is determined to stay independent in their distribution, other airlines have adopted the strategy to push products to consumers via multiple channels.

According to Delta Airlines' CEO Leo Mullin, the Internet has enabled his company to generate incremental revenue by providing different value propositions to different segments of travelers.

-

Delta.com designed for very loyal business travelers from larger corporations

-

Orbitz.com, financed by American Airlines, Continental Airlines, Delta Airlines, Northwest Airlines, and United Airlines, targets the general leisure segment

-

Priceline.com lures the price-conscious travelers

-

Site59.com attracts those looking for last-minute deals

-

MYOBtravel.com helps small companies take complete control of their business travel

By partnering with these other discount websites, Delta can better manage distressed inventory by selling off unsold seats. Furthermore, with the consumer data harvested through these sites, Delta migrates selected price-conscious travelers to become loyal customers by offering targeted promotions.

In the past, travel agencies were responsible for booking 85 percent or more of the airline tickets purchased, but in the last five years, airlines have drastically cut the commissions they pay to travel agencies. Delta and American Airlines, for example, eliminated travel agent commissions this year. The lack of commissions from airlines has unfortunately forced travel agencies to charge fees for their services.

Despite this negative impact on travel agencies, agencies can offer the advantage of speed—often agents can find in minutes fares that take consumers hours to locate. In addition, the Internet is a valuable tool for travel agents themselves. Agents can access resort, cruise, and tour websites, which provide information that agents can then tailor and pass on to their clients.

Since its debut in March 1996, Travelocity has gone from being the 33,000th largest U.S. travel agency to the sixth largest in terms of gross travel bookings. Travelocity's business model is to provide travelers with choices and control at the best price, but not necessarily the lowest price. "We provide our customers savings in terms of time, as well as money, by offering great choices, deals, 24/7 customer service and convenience, such as FareWatch emails," says Mike Stacey, director of loyalty at Travelocity.

As the leading online travel agency, Travelocity is much more than a website that sells plane tickets. In the wake of airlines' zerocommission policy, Travelocity is diversifying its revenue mix to rely less on transactional air-ticket sales and more on high-margin products like cruises and vacation packages. Although airline tickets remain the biggest segment of Travelocity's business, much of Travelocity's growth has come from other travel needs. According to Stacey, the website experienced a 1,000 percent growth in cruises between February 2001 and February 2002. Having realized that consumers look for more personal interactions when it comes to purchasing complex products like cruise packages, Travelocity recently added call centers in Pennsylvania and Virginia that focus strictly on cruise and vacation sales. Shoppers can now call Travelocity's trained agents seven days a week for information or even to book via the phone. "We are not defining ourselves as an online travel site, but more as a travel agent," says Stacey.

To further reduce reliance on air commission, Travelocity recently agreed to buy Site59.com Inc., a last-minute travel company, for $43 million. Site59.com, named for the 59th minute in an hour, sells bundled vacation packages through partnerships with hotels, rentalcar companies, and airlines. Acquiring Site59 will enable Travelocity to expand its high-margin merchant business, in which it buys hotel rooms and airline seats on consignment at a discount, and then sells them for profit.

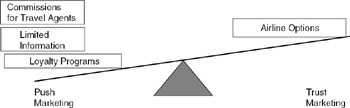

As is evidenced by the diagram in figure 5.2.2, prior to the Internet, the travel industry was dominated by push marketing. The airlines held most of the power and were able to manipulate consumers through the use of loyalty programs, limited information, and by paying travel agents commissions to act as distributors. Although there were multiple airlines, price comparison information between airlines was not easy because it required phoning numerous airlines.

Figure 5.2.2: Balance between push and trust marketing before the Internet.

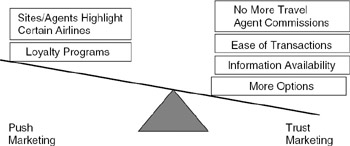

After the Internet (figure 5.2.3), we see that loyalty programs are still an aspect of push marketing, and some websites and travel agencies still choose to highlight certain airlines instead of being unbiased. The bulk of the weight, however, has now shifted to trust marketing. With the Internet, consumers have the luxury of more options, more information, and simpler transactions. In addition, because many airlines have stopped paying commissions to agents, agents can be unbiased when locating low fares for their customers. All of these changes have resulted in the development of an industry in which consumers hold a significant amount of leverage.

Figure 5.2.3: Balance between push and trust marketing after the Internet.

Global Power and Responses

Whereas the United States has led the way in moving travel booking onto the Internet, an increasing number of non-U.S. industry players have entered the market as consumer advocates.

Europe

According to Jupiter mmxi, the European online travel market generated euro 4.3 billion in 2001. Unlike in the United States, where major online agencies outrank most airline websites in terms of sales, budget supplier websites dominate the online travel market in Europe. However, the same trust-based online strategy seems to be working in both markets.

Since its launch in 2000, ryanair.com has quickly become the largest travel website in Europe. Ninety-one percent of seat sales are sold via the Ryan Air website, while the rest is booked through call centers. The formula for success seems to be its special homepage promotions and its guaranteed lowest Internet fares. Ryanair.com "guarantees all Internet users that the air fares purchased at http://www.ryanair.com are the lowest available on the Internet."

To stay in the Internet game, nine European airlines launched a webbased travel agency in December 2001. The website, Opodo, targets leisure customers who surf websites looking for bargain fares. Besides airline websites, travel aggregation sites such as Expedia, Travelocity, lastminute.com, and ebookers.com are among the top travel sites in Europe.

Asia

For the most part, Asian consumers use the Internet to gather information, rather than to make purchases. Unlike the United States, where most airlines are fairly homogeneous and most travel is done within the country, travel in Asia is usually outside the country of origin, entailing visa and passport issues that require an agent's personal service. Many are betting, however, that simpler online transactions and price comparisons will encourage more Asians to buy more travel over the Internet. U.S. companies, such as Priceline, are forming joint ventures with Asian conglomerates in order to offer travel in Asia. Also, similar to the U.S.-based Orbitz, Japan Airlines, All Nippon Airways Co., Japan Air System Co., and major U.S. and Asian airlines have launched a Japanese one-stop online travel Web site called Tabini. Similarly, 11 Asian airlines have established agreements to launch Zuji.com for the Asia-Pacific market.

Forecast for Industry

Travel agencies, both big and small, are here to stay. Online and offline boundaries will disappear. Empowered customers will push airlines to simplify their pricing structures.

Delta, American, and Continental airlines have eliminated commissions for most travel agencies in 2002. Following the lead of the airline industry, Hertz Corp. announced elimination of commissions to travel agents handling negotiated corporate and government accounts in the United States and Canada. We believe that travel aggregators will continue to play the important role of consumer advocate, via the Internet or other future technology platforms. Nonetheless, not all agencies will survive. The small online-only agencies will likely face major consolidation. Large agencies will survive because of their negotiation power. For example, travel agencies like Travelocity and Expedia have sealed marketing partnerships with most major airlines to replace the eliminated transactional commission fees. Furthermore, major online players are becoming wholesalers—buying discounted seats and rooms from airlines and hotels, and making money by marking up and bundling extras such as theatre tickets or dinner reservations. Currently, only one-quarter to one-third of Expedia's revenue comes from airline commissions, and Priceline does not rely on commissions at all. Large corporate travel agencies redesigned their businesses to rely on customers to pay transaction fees, rather than relying on commissions from suppliers. According to American Express's 2001 Annual Report, 70 percent of AmEx's travel revenues came from customer fees and only 30 percent came from suppliers.

We predict that small, independent agencies will form a "super agency" to negotiate for incentive commissions. The survivors will be niche and specialized agencies that work closely with popular vacation destinations, such as the Caribbean and Jamaica. These agencies provide value to consumers by offering trusted expert advice (perhaps certified by the destination tourism authority) that is richer than the static information posted on travel websites. To better serve travelers' needs, they will form alliances with local entertainment and tour providers to create customized vacation packages. They will likely charge both suppliers and customers fees to cover the higher expenses.

The boundary between "click" and "brick" will disappear as companies serve different customer segments. Travelocity customers can place orders online or call trained agents by phone for advice. Priceline is considering adding call centers and retail kiosks to its Asian operations to overcome potential online skepticism from Asian consumers. Likewise, "bricks" travel industry veteran Thomas Cook added e-commerce capability to its website and became the fourth most visited travel site in the U.K.

As our data has shown, the Internet has become a critical channel to sell travel products, but it will not be the only channel. We predict that the distinction between online and traditional travel agents will disappear, and companies will use multiple channels to meet consumers' needs in whatever manner is most appropriate.

The Internet empowered travelers by providing them with easier transactions, more information, and more options. Because of the intense competition for travel dollars, consumers can now choose from a variety of ways to buy travel: through a traditional agent, through an aggregator site, or by booking directly with the supplier. As we mentioned, instead of fighting this rising consumer power, travel industry players are embracing it by offering simplified fare structures (Southwest), low-price guarantees (Ryanair), easy and unbiased price comparisons (Orbitz) and convenient transactions (Travelocity). Is this a paradigm shift or simply an aberration? We believe it is a paradigm shift, because companies with a trust-based approach will be the only ones that empowered consumers accept.

The Automotive Industry

Industry Structure

The Internet is having a tremendous impact on consumer behavior in the U.S. automotive industry, which measured 17.4 million vehicles sold in 2001.[1] Although Internet sales account for only about one out of every twenty new vehicle purchases, more than 60 percent of all new vehicle buyers research their vehicle online before purchase.[2] Those who use the Internet visit 6.8 websites on average and focus on two types of websites—original equipment manufacturer (OEM) sites and the third-party independent sites. Seventy-eight percent say they visit at least one OEM site. Table 5.2.2 shows the increase in Internet use in the vehicle purchase process.

| 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| | ||||

| Percentage of customers who use the Internet for research purposes in the new-vehicle shopping process | 25% | 40% | 54% | 62% |

| Percentage of new vehicles that are sold through an Internet channel | 1.1% | 2.7% | 4.7% | 6.0% |

| Source: JD Power and Associates. An online buyer is defined as a new-vehicle buyer who purchases their vehicle from the same dealer to whom they are referred by an online buying service. | ||||

The majority of Internet shoppers first visit a third-party site to compare vehicle specifications, narrow their consideration set to a few models, and then review detailed information for each model at the manufacturer's site. Next, the consumer returns to a third-party site and/or an Internet Buying Service (IBS) to perform detailed comparisons of pricing and financing. At this point, it appears that a majority choose to purchase offline, although inadequate responses from dealers to online inquiries may contribute to this decision. Interviews with dealers confirmed that they perceive Internet consumers to be more informed about features and pricing than non-Internet shoppers. These customers usually have more realistic views of fair pricing, which shortens the time spent selling a vehicle and negotiating a price. One dealer reported that it was not uncommon for a customer to bargain with a computer printout of a competitor's price or some assessment of fair market value.

For those who attempt to buy through an Internet buying service, the Internet has a mixed impact on consumer power. On the one hand, only 12 percent of new-vehicle leads sent to dealers through an online buying service actually result in a sale. Most leads are either not adequately served or are not serious leads.[3] A customer submits information detailing their vehicle of interest along with other basic personal information (i.e., zip code and contact information). The IBS uses this information to group leads by profile and then distribute them to the dealers awarded exclusive territories or, in some cases, to sell to the dealer who bids highest for that category of lead. In the latter case, rather than being based only on inventory and geography, the inquiry goes to the dealer with the highest interest and presumably greatest capability in servicing that customer profile. This matching process can benefit both the dealer and the customer, because it potentially introduces a greater efficiency to the shopping process for all parties. The dealership saves money on marketing and customer acquisition costs compared to the traditional recruiting process, and the customer saves time in the shopping stages while also having the convenience of beginning the shopping process from home.

The current industry structure is mostly an extension of the pre-Internet structure. The primary difference is that information and resource players, who were once a minor influence, have developed into a major influence in the industry. This is due to the emergence of the Internet as a high-quality source of information for consumers, to which some OEMs and dealers are scrambling to respond.

The first movers into the Internet space were third-party information providers and vehicle purchasing referral services, although the distinction between these two entities has been blurred over the past several years through alliances, acquisitions, and joint marketing agreements.

Although some of the most popular sites are Internet extensions of brick-and-mortar companies like Kbb.com of Kelly's Blue Book or edmunds.com of Edmunds, many of the popular third-party information sites provide services only on the Internet, such as Carpoint.com, AOL Auto, and AutoVantage.com. These companies strive mainly to provide information and impartial recommendations.

Another type of entrant is the Internet Buying Service (IBS), such as Autobytel.com, CarsDirect.com, and AutoNation's etailNetwork. These firms forge marketing relationships with dealers and serve as intermediaries to help consumers reach purchase agreements with dealers in exchange for a commission. The generation and sale of customer leads via the Internet has rapidly developed into a complex, multilevel distribution system. There are agents who sometimes serve as wholesale middlemen aggregating this demand information and selling it to dealerships. The high customer acquisition costs that dealers incur through the traditional marketing process (generally on the order of several hundred dollars per customer) allow great potential for improvement through Internet lead generation. The consumer also benefits, because many of these services offer a combination of nohaggle pricing and convenience.

Another segment of third-party information providers is aggregators such as Automotive Information Center (AIC), which is part of Autobytel Inc., and Autofusion. These companies are more shielded from the public's attention, and their main role is to aggregate vehicle detail content and sell access to other website providers.

Not to be left out of the Internet action, manufacturers and dealerships have made varied levels of effort in their online presence. Most manufacturers have introduced websites that are aimed at providing and collecting information, much like an interactive brochure. FordDirect.com and GM BuyPower connect consumers to their dealer networks with access to inventory, vehicle configuration tools, and current incentives.

Dealer websites vary widely, from being basic online advertisements to having many advanced capabilities such as a virtual showroom, updated inventory status, and online vehicle service scheduling. Inconsistent response by dealers to sales inquiry e-mails from customers demonstrates this variation among dealer websites. One study found that only 42 percent of such inquiries received responses, and less than half of the responses received included all the information requested.[4] In contrast, two dealers we interviewed who are focused on developing online sales have succeeded in attaining significantly larger market share through online sales.

Evidence of Power

Customer power seems to derive from three sources: more purchase options, more valuable and timely information, and the degree of transaction simplicity. That is, car buyers can search among a greater number of dealers, are better informed, and can simplify the negotiation process with no-haggle and online fixed pricing (figure 5.2.4).

More Options:

-

Traditional Dealers

-

Online Dealers

-

Internet Buying Services

More Information:

-

Free Access to Specification and Pricing Information

-

Online Buying Guides

-

Interactive Comparison Tools

Simpler Transactions:

-

Online Dealer and IBS Quote Requests

-

Online Fixed-price Quotes

Figure 5.2.4: Forces affecting power in the auto industry.

Customers can now choose between the traditional buying process and the online process, or some hybrid of the two. In addition, the Internet enables customers to cross-shop among dealers over a larger geographic area and increase the set of competing dealers. Although a relatively low percentage of consumers actually commit to making a vehicle purchase online, the IBS and Manufacturer Referral Sites (MRS) have nevertheless increased customers' geographic access to dealers. Recent evidence shows that buyers who use the Internet for price quotes typically drive 10 miles farther to purchase a vehicle than those who do not.[5]

The Internet has provided broader and lower-cost access to high levels of information, and usage statistics show that greater numbers of customers are accessing this information. In particular, studies cited that access to detailed information on dealer invoice pricing, online buying guides, extensive comparison tools, and dealer inventories is improving the convenience and quality of information for a great number of consumers. The consensus among the dealers we interviewed is that customers are more informed about what they want, what they are willing to pay, and what their purchasing options are.

The obvious manner in which the Internet has helped simplify the purchase process for customers is the no-haggle, fixed-price offerings by the IBS. Once a customer selects a vehicle, these online services provide a convenient means to complete most of the transaction by computer. Less apparent is the effect of the increased access to data. Many websites provide tools to help manage all the data—from basic vehicle comparison tools to sophisticated interactive decision advisors. Anecdotally, the evidence points toward a shorter purchase process at the dealership for customers who have researched online. That is, dealers report that the transaction process was shorter with well-informed customers because they tend to have more knowledge about vehicle specifications and a better understanding of fair pricing.

These changes in the purchase process lead one to expect that if customers have access to more information, lower search costs, and easier access to a larger number of dealers, they are experiencing increased bargaining power in the form lower prices. Indeed, one study comparing prices paid by online purchasers to offline purchasers found that IBS customers are in fact realizing lower purchase prices.

Strategic Response of Participants

Vehicle manufacturers have taken advantage of the Internet effect to cultivate a better relationship with consumers. The Internet has proven to be a powerful point of contact that enables two-way communication with the consumer. One recent initiative, which aims to expand the role of the manufacturer, is Auto Choice Advisor, created by General Motors (GM). This website service provides impartial recommendations from a database of over 300 vehicles, most of which are non-GM products. The consumer enters a variety of preferences for major attributes, and the website applies an algorithm to rank order the "best" vehicles based on the individual preferences. GM hopes this tool will provide meaningful insight into which vehicle attributes customers value most. The success of this website depends largely on how much trust the consumer is willing to place in GM as a source of advice, which GM is attempting to bolster by partnering with trusted sources such as JD Power and AIC.

Manufacturers are also experimenting with Internet sites that support dealer sales operations and connect consumers with local dealerships. However, simultaneous efforts by manufacturers to acquire an ownership stake in some dealership operations has overlapped with these Internet efforts and created confusion and skepticism within the dealer community. Both Ford and General Motors have experienced resistance from their dealer networks in their attempts to strengthen the Internet link from consumer to dealer via the manufacturer website. Some dealers see this as part of a larger strategy by the manufacturers to assume control in the selling process, a power that dealers will not voluntarily surrender.

Once heavily threatened by the potential of the Internet as an alternate purchase channel, the dealer network has responded with its own Internet tools. The response, however, has been slow owing to the federal franchise laws that require all new vehicle sales be made through an authorized dealership, thus reducing the perceived threat from the Internet entrants who cannot sell directly to consumers.

The Internet has presented dealers with an opportunity to redefine their relationship with the consumer. The task is not easy, though, because the industry suffers from a long history of strong distrust between consumers and dealership sales representatives. The most progressive dealers have responded by establishing a customized sales process to cater to Internet-savvy consumers. Since many consumers now walk into a dealership with full knowledge of invoice pricing and vehicle availability, there is higher potential for a trust-based sales process, with more emphasis on matching a customer with their desired vehicle, and less effort on trying to manipulate the customer's opinion.

In terms of the "push versus trust" scale, dealers find they have elements on all three areas of the scale. The fact that there are a substantial number of buyers that focus exclusively on the bottom-line price means that dealers should not abandon the push process with these customers, as there is little chance to make a sale with a full-trust, upfront price disclosure sales approach. Early recognition by sales representatives of which buyers are in this deal-prone segment is important in being able to effectively employ the push strategy without alienating the rest of the customer base that might be more receptive to a trust strategy.

As more customers rely on the Internet for research in the shopping process, the scale clearly tips toward the trust side. The customer armed with Internet information is able to quickly verify dealer claims about invoice pricing, options content, and even regional availability. Thus, the Internet presents a breakthrough opportunity for dealers to change the mindset of many customers in how they perceive the trustworthiness of the dealership. As the role of the Internet continues to expand in the automotive sales industry, the effectiveness of trustbased strategies is expected to increase. Although dealers are caught in the middle between push and trust today, the industry appears to be steadily progressing towards the full-trust model in the long term.

Internet companies, which positioned themselves between consumer and dealer, are beginning to find themselves squeezed from all directions. The Internet space is crowded. Advertising revenue models have proved unsustainable, so many of these online companies are forced to find alternate sources of revenue. This struggle has prompted the beginning of "Super Sites," which aim to provide full-service capability from one source. These services range from information, ratings, recommendations, buying services, financing referrals, and even insurance referrals. The best evidence of this trend is seen in Autobytel Inc., which in 2001 acquired a host of smaller companies such as Autoweb.com, Carsmart.com, Autosite.com, and AIC.

Third-party information providers find they have an advantage over dealers and manufacturers in that consumers trust these independent sites the most, as confirmed in many surveys. However, there is no evidence that consumers are willing to pay for information, especially since they are accustomed to accessing it for free. In order to stay in business, many of these companies rely on sales-lead generation and sale to dealerships. In this regard, these companies face an enormous challenge. They must maintain consumer trust when providing accurate information, convenience, or efficiency in the shopping process. At the same time, they must generate high-quality leads that can be sold to dealerships in order to secure a source of revenue.

Therefore, the Internet companies must expand their services to continue luring customers without compromising the perception of trust. For example, Edmunds.com provides consumers with a TMV (True Market Value) for any major make and model, new or used vehicle. Since most consumers view Edmunds as an unbiased and trustworthy source of information, it is no surprise that Edmunds's website commonly ranks as one of the most useful sites in consumer surveys. A strong brand name, impartial position, and leading-edge features are critical to staying in the Internet domain as a third-party service provider. Ultimately, there are only a small number of companies with these resources, and so the wave of proliferation in websites that occurred in the 1990s is expected to quickly reverse through a period of consolidation, alliances, and failure.

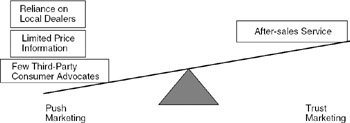

The unflattering stereotype of the pushy car salesman is one that is familiar to anyone who has purchased a vehicle from a dealership. Unfortunately for consumers, it exists for good reason. Before the Internet, dealer sales representatives could be pushy because it paid to do so. Consumers generally had little knowledge of invoice pricing and were unfamiliar with what inventory they could expect the dealer to have. Furthermore, finding out what inventory other dealers had typically meant visiting those dealerships—an inconvenient, timeconsuming process. Consumers found themselves relying on the dealership for almost all of the vehicle information, a scenario that rewarded pushy sales tactics (figures 5.2.5–6).

Figure 5.2.5: Balance between push and trust marketing before the Internet.

Figure 5.2.6: Balance between push and trust marketing after the Internet.

With the Internet, consumers have as much information as they want, including pricing and even dealer inventory. As a result, educated consumers can walk into a dealership and tell the sales representative exactly what vehicle they want, how much they are willing to pay for it, and where they will go for the next best alternative in the event that negotiations at the first dealership fail. The major factor that keeps the scales from tipping further in the direction of trust-based marketing is that there are still about 40 percent of consumers that do not conduct research on the Internet, and so the dealerships that are quick to identify these consumers are still able to rely on push marketing.

Global Power and Responses

Outside of the United States, the impact of the Internet on automotive shopping has been most prominent in Europe, a market largely similar to the United States. European markets have also seen the emergence of rapidly growing automotive websites that provide research tools for pricing, specifications, options, and availability.[6] This market is experiencing a lag of about one year compared to the United States in terms of percentage of new car shoppers that use the Internet in their search process. This effect is due primarily to the overall lag of Internet adoption in Europe compared to the United States.

One major impact of the Internet in the European market has been on unofficial imports across national borders. Owing in large part to highly variable tax structures in different countries, the prices of automobiles can vary by 30 to 50 percent from one country to another. Britain, the most expensive new-car market in Europe,[7] has seen a surge in vehicles that are imported into the country by individuals purchasing in lower-cost countries such as the Netherlands. More than 5 percent of new car registrations in Britain are now from unofficial import purchases. Figures for Germany, Austria, and France are also on the rise.

The Internet is a major enabler to this import process, giving broad access to pricing and availability in other countries. In fact, importing intermediaries, which operate primarily through a website, are providing shoppers with nearly all the vehicle information as well as transaction logistic details needed to make a purchase. In contrast, dealers in low-price countries are taking a cautious approach to selling cars for export. They have avoided overt promotions of this business, citing contractual arrangements with the manufacturers. However, by law, any EU citizen can freely purchase a car in any EU country. Empowered by pricing and logistical information, British customers are finding it easier to import cars and can even schedule a "Car Cruise" journey for the round-trip journey to select their vehicle.[8]

Forecast for the Industry

Manufacturers have opportunity and ample resources to build powerful, sophisticated Web sites with convenient tools to enhance the shopping and ownership experience. Manufacturers also have the advantage of strong brand names which consumers are more willing to associate with trust and honesty in information. We expect that the presence and appeal of manufacturer websites will grow steadily in the coming years.

Dealers are currently still on the opposite end of the trust scale, but they benefit from the tremendous potential which the Internet provides in building trust-based sales strategies. Although the learning process has been slow, dealers are beginning to better understand how to segment the customers who will respond favorably to trust-based marketing. While the dealer network as a whole has a long way to go in this regard, the startling success of a few savvy dealers who aggressively use the Internet to reach a wider customer base is an indication of the future. That is, those dealers who have used the Internet to lower costs, like customer acquisition expenses, are able to enhance market share and increase profits even when selling at lower prices. The transparency of successful Internet tactics encourages imitation, and so it is just a matter of time before best practices are common throughout the dealer network.

The outlook for third-party Internet companies and buying services looks difficult assuming that manufacturers and dealers move toward trust-based marketing. Although the Internet information providers are currently rated as the most useful and most trusted sources for the research process, generating revenue while maintaining this image presents a challenge. Charging consumers who are accustomed to free information looks less than promising, and relying on advertising too much could threaten the image of impartiality. The most promising source of revenue for these Internet companies is the sale of customer leads that they can generate through buying services. However, as manufacturers enhance their dealer referral online tools, and dealers expand their ability to generate their own leads, the strategic advantage of third-party sites dwindles rapidly.

The extent to which one considers the Internet to be a paradigm shift in the automotive industry depends on one's initial vision of the Internet. For those that saw the Internet as a new way to purchase cars that would obsolete the existing dealer network in favor of virtual dealers, the Internet has been an aberration. Consumers have shown a preference for "kicking the tires" prior to making a purchase, and dealer franchising laws protecting the traditional process for completing a sales transaction have been upheld.

From the standpoint of reaching customers in the research process, the Internet has indeed created a paradigm shift. The business of marketing to consumers in the automotive industry is undergoing a radical shift in reaction to the increase in consumer power. The ability of customers to aggregate information, compare brands, and shop across dealers of the same brand is increasing in scale and scope. Because early evidence indicates that dealers who respond with "trust-based" marketing are showing success, we believe that they will be positioned best for taking advantage of the Internet to develop customer relationships (table 5.2.3).

| Name of Web site | New car buying New car information | process |

|---|---|---|

| | ||

| Information aggregators Kelly Blue Book (KBB.com) | car reviews, car and option pricing, buying advice, interactive decision guide | provides a choice of clickthrough to IBS, MRS, local dealer if available |

| Cars.com | car reviews, car and option pricing, buying advice | provides a choice of local dealers for requesting price quote |

| Internet buying services (IBS) AutoVantage.com/AutoNation | car reviews, car and option pricing, buying advice | Provides quote request form for AutoNation etailNetwork |

| Carpoint.com | car reviews, car and option pricing, buying advice, interactive decision guide | forwards quote request to network dealer |

| CarsDirect.com | car reviews, car and option pricing, quotes advice | provides fixed online buying |

| Manufacturer referral sites (MRS) Ford.com/FordDirect.com | car and option pricing, interactive decision guide | provides access to dealer inventories and forwards quote requests to dealers |

| GMBuyPower.com | third-party comparison reviews, car and option pricing | provides access to dealer inventories and forwards quote requests to dealers |

| Dealer sites DriversSeat.com (NADA) | car reviews, car and option pricing, links to manufacturers | provides choice of local dealers to request price quote, some access to inventory |

| Autonation.com | car reviews, car and option | access to inventory pricing and quote request |

| (JD Power 2001 New Autoshopper Study, 1/02) | ||

The Healthcare Industry

Industry Structure

Pharmaceutical companies face new challenges to their business model with the emergence of Internet infomediaries. Today's business model is not a one-dimensional supply chain, but a supply web with new links in the traditional chain. Internet infomediaries are these new links. Internet infomediaries are Web sites that allow buyers to bypass traditional sales and distribution links. They provide a more direct conduit between pharma companies and patients. This emerging link in the supply chain puts patients in touch with pharma companies in an easier, faster, and cheaper fashion.

Infomediaries such as online pharmacies are more efficient because patients don't have to drive to a drugstore and wait in line to fill prescriptions. The online option is often cheaper because it eliminates several layers of overhead. In addition, infomediaries provide not only products but also information on drugs, doctors, hospitals, counseling, and other services—one stop shopping at its best. Infomediaries are empowering patients to become better informed and more active in managing their own health.

The number of American e-health consumers (i.e., all Internet users that access health information) in the first quarter of 2001 was 45.8 million, 52 percent of the total active online adult population. Internet and e-health users are forecasted to reach 81.6 million in 2006. The growth of e-health and the momentum provided by the empowered healthcare consumer is strong, with a positive outlook for continued growth.

Historically, pharmaceutical companies have operated in a patentprotected vertical integrated market, where they dominated the whole supply chain from early stage development to manufacturing, marketing, and distribution. Their goal was to educate doctors on the benefits of their drugs and create high incentives for them to prescribe the drugs.

The pressure of Healthcare Management Organizations (HMOs), however, coupled with the development of generics, the increasing demystification of the doctor role, and the increasing flow of information, has made pharma companies shift their focus to the patient. Regulatory changes now permit pharmaceutical companies to advertise directly to consumers, which can create brand awareness and build trust and loyalty. While the upstream value chain remains unaltered, the underlying assumptions of marketing and distribution have changed significantly. Nowadays, patients are much better informed about their diseases, and they ask their doctor about what medicine they want to take. Medical doctors find that "patients now come to the clinic better prepared and able to discuss the issues related to their illness. They ask pertinent questions and they look for second opinions."[9]

The Internet accelerates consumer power because it provides an easy-to-find space for information to flow rapidly and allows new infomediary business models. Websites like WebMD, Yahoo!Health, and AOL Health play the customer advocacy role in the industry to attract new visitors to their networks.

Evidence of Power

Although it is clear that the power of the health consumer is increasing, the potential to change is far from being met. Analysis was performed on three dimensions: more information, more options, and simpler transactions (figure 5.2.7).

More Options:

-

More Treatment Options (different drugs, different options)

-

Increased Rivalry of Generics

-

Tiered Co-pays Offered by Insurers

More Information:

-

Increase in Direct-to-Consumer Marketing

-

Emergence of Online Information

-

FDA Regulations Require More Disclosure

Figure 5.2.7: Forces affecting power in the healthcare industry.

About 52 percent of the adult American population has already used the Internet to search health information.[10] A lot of information is available: from drug manufacturer corporate websites, product-specific websites, disease management programs, online pharmacies and PBMs, managed care organizations, federal and state agencies, mass media, and generic portals. Consumers see the Internet as a way to seek information about health for themselves or others and to get a second or third opinion in an anonymous way. According to a Cyber Dialogue Inc. Survey in 2001, two-thirds of adults view the Internet as a potential solution to reduce medical errors.

However, the information is still difficult to find, hard to trust, and hard to use. Irrelevance of information and concerns about trust and privacy are the main problems with health websites today.

Information about drugs is not easy to quantify and, therefore, drugs are difficult to compare. Regulations allow drugs to be compared,[11] as long as companies provide adequate evidence of the claims made. But, this evidence can be very costly,[12] because it often has to be built on drug-to-drug clinical trials. Drug-to-placebo data could not support drug-to-drug comparisons. None of the above-cited players has a tool that compares therapies for a disease or drugs within the same category.

The process of purchasing a drug remains complex because of the number of players involved. Consumers must have prescriptions from their doctors, and HMOs have a say in which medications are reimbursable at which levels.

Nonetheless, these relations might change as more information becomes available and health expenses increase on household budgets. Patients with chronic diseases, like asthma, tend to both know everything about their disease and be more concerned (or otherwise be pressured by HMOs or health insurers) about the cost of therapy. They are therefore more involved in the transaction. Consumers who are subject to chronic diseases, or have relatives who are, show a higher tendency to purchase products online (33 percent) compared to those consumers who have no history of chronic illness themselves or in their families (27 percent). This effect may be caused by a higher price elasticity of demand and higher predictability of the needs from the chronic patients. The use of lifestyle drugs (like diet-related therapies) or the presence of children also increases the tendency to purchase online.

Strategic Response by Industry

Big pharmaceutical companies seem to be trying different approaches to reach the online consumer, running tests on several Internet business models. The different responses made by pharmaceutical companies can be categorized into four groups:

Drug manufacturing companies have built large corporate websites. As well as in other industries, some of these websites broadcast corporate information for investors, industry experts, or job seekers. However, for some of these companies, the corporate website is integrated with e-strategy and works as a marketing tool. These websites offer a variety of services like medical publications, software, etc. For example, Merck offers an interactive version of its well-known "Merck Manual" at its corporate website.[13]

One of the most common Internet approaches is to build product websites for branded drugs. Merck's Vioxx.com and Pfizer's Viagra.com are good examples of proprietary sites that build brand loyalty with consumers. These websites help companies build and support communities around a product or therapy, providing useful technical information both for consumers and healthcare professionals and, sometimes, lifestyle counseling. Product websites are aimed at consumers and at healthcare professionals. The success of these websites is not easy to measure. Little is known about how many visits to Vioxx.com can actually be transformed into a visit to the doctor about arthritis.[14]

Another successful model is the disease education website. Drug manufacturers provide information about diseases on websites, without mentioning their specific therapy or product. The goal of these websites is to educate the consumer and increase the number of visits to the doctor about a certain disease. Drug manufacturers expect conversations between doctors and patients about the disease to increase and to be more efficient. Doctors sometimes find that consumers know too much, but they like the fact that information can be easily updated.[15] Merck's thinhair.com or GSK's iBreathe.com are examples of this type of site.

Merck is also providing health services to healthcare professionals—through merckmanual.com and merckmedicus.com—and to patients, through mercksource.com.

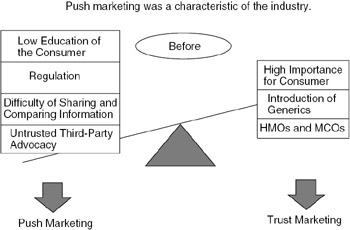

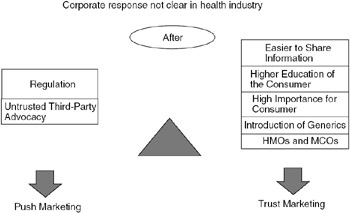

The options of trust versus push marketing differ in their approach to the customer. Product websites, for instance, seem to be oriented toward one-time transactions and focus on giving information about the product and educating the consumer on the need to visit the doctor and have a smarter conversation about the disease. Community websites and medical information websites look forward to a longer relationship and try to build trust with the consumer (figures 5.2.8–9).

Figure 5.2.8: Balance between push and trust marketing before the Internet.

Figure 5.2.9: Balance between push and trust marketing after the Internet.

Pharmaceutical companies have moved to building their brands within the consumers, creating awareness of their products and knowledge about the diseases. This is recognition of the increasing power of the consumers.

Global Power and Responses

As Amazon.com allowed books to be sold globally—and thereby partially put an end to local monopolies—the same is happening with drugs. Before the Internet, some Americans would travel to Canada to fill their prescriptions in order to save money. Now, with the Internet, the process is even easier and other companies around the world might enter this global business. This poses high threats to some countries' debilitated national healthcare systems and raises ethical issues about monopolistic pricing policies, participation of the government, length and extent of patent protection, and level of competition allowed in these markets.

Another interesting shift towards globalization is the possibility that patients have better access to a second opinion from a doctor and may search for the world expert in the matter.

Forecast for Industry

Regulations play a major role in the healthcare industry. On the one hand, politicians feel the pressure of increasing costs of health care, especially those related to prescription drugs, and they might be compelled to foster competition among different companies. Similarly, HMOs and MCOs are working to have generic drugs on the market as soon as patent protection periods end. On the other hand, politicians still have to protect pharmaceutical companies to the extent that they are the source of innovation in the drug development area.

So far, it is not clear which player will be a customer advocate and gain the trust of consumers. The doctors were the source of trust in the past, but the pressure of both pharmaceutical companies on one side and HMOs on the other has recently created some mistrust. It should be noted that in the early days, HMOs presented themselves as the future customer advocates and ended up focusing too much on costs and less on benefits for consumers.

Insurers could be customer advocates for healthcare services. Insurers have incentives to take a long-term view and establish a relationship rather than a mere transaction, which could make them move toward trust. However, insurers will end up paying for variable healthcare costs against the fixed fees paid previously, which will make them hard to trust.

Pharmacies have high interaction with customers and have an incentive to focus more on the relationship than on the transaction. In a business model that takes a fee out of each product sold, pharmacies have to trade off possibly higher revenues today with higher trust and possibly more loyal customers tomorrow.

The Internet is not, as many once believed, a mere diversion for small groups of doctors who are technophiles. Rather, the Internet is widely used by doctors to increase their knowledge. Also, large pharmaceutical companies have realized the importance of the Internet in conveying the right message about a disease and the drugs to cure such diseases. This vehicle is also a key way to reach the doctors who regularly see a large number of patients. Pharmaceutical companies and MCOs have spent billions of dollars to reach these targets through offline channels.

From this study, we feel strongly that healthcare industries as a whole are slowly moving toward trust-based strategies through the Internet as a medium. The industry—which has been very closed in its approach over the centuries, highly regulated, and closely monitored by governments—will not quickly break away from the traditional push-based way of doing things. Pharmaceutical companies protect their revenues through whatever legal channels are possible. They have slowly begun to realize the importance of gaining consumers' confidence, respect, and loyalty not just for their brand products, but also for their company as a whole. Thus, we have seen increased spending by these players in direct-to-consumer marketing online. This spending is still far less than the traditional channels, but we see a slow shift that is critical on a long-term basis. We also see a strong trust-based approach in the online sites for health advocacy groups. Some of the sites are sponsored by large pharmaceuticals, which suggests that on one hand they are pushing their drugs to the consumer and on the other hand they understand the importance of trust creation among the consumer group. Also, we see a strong effort being made by the intermediaries to create neutral sites to help doctors and consumers in making the right choice of drugs.

Although we cannot say the behavior is a paradigm shift at this stage, we predict that in the next five years a strong shift is going to be evident. It may not match the timeframe of other industries like travel or automotive, but it will eventually catch up as more and more healthcare players see their ROI increasing through use of the Internet.

Conclusion

Our research has found evidence across industries of growing consumer power. The Internet makes it easy for customers to learn about products and services, to compare offerings between companies, and to read third-party evaluations of product/service performance. The Internet also provides a new channel for buying products and services, which gives customers more options in buying a given product or service. Finally, the Internet makes transactions simpler, removing the need for haggling or automating them via online auctions.

Companies across industries are responding to the changes brought by the Internet. Leading companies are creating comprehensive websites that not only provide depth of information and enable transactions, but that seek to build ongoing relationships with customers. Although push-based marketing strategies still work in situations where customers are relatively uninformed, we're seeing a shift toward trust-based marketing. The premise of trust-based marketing is an honest sharing of information with the customer—being an advocate of the customer. In some cases, being an advocate of the customer means recommending a competitor product, as we saw in the case of GM's Auto Choice Advisor, which recommends either GM cars or competitor cars based on the each customer's specific needs. Although such marketing strategies seem counterintuitive at first, trust-based businesses can extract themselves from margin-killing price competition by proving to customers that they deliver true value. Trust-oriented businesses have high customer retention and more stable revenue streams. Ultimately, we predict that trust-based businesses will have higher sales volumes and lower marketing costs than pushbased businesses.

Our research, and the evidence presented here, suggests two major implications for management education. First, we suggest making trust the focus of basic marketing courses. Second, we recommend that advanced marketing courses provide a deeper view into the trustbased strategies associated with marketing, including trust-based product development, trust-based selling, trust-based pricing, and trust-based advertising and promotion. Each aspect of marketing has a trust-based component, and an emphasis on trust changes the traditional approach to each of these marketing activities.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our appreciation to the managers at the following organizations that were instrumental in our understanding of industry dynamics. Their insightful comments proved helpful during our research process. We would like to thank AMR Corporation; Autobytel, Inc.; AutoNation, Inc.; Aventis Pharmaceuticals Inc.; CVS Corporation; Federal Drug Administration; Ford Motor Company; General Motors Corporation; Harvard Medical School; Herb Chambers Companies; JD Power & Associates, Inc.; Lee Travel; Massachusetts Office of Travel and Tourism; Merck & Co., Inc.; Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc.; Orbitz; Pfizer, Inc.; Travelocity.com L.P.; and Yatra Corporation.

[1]Automotive News, January 7, 2002.

[2]JD Power and Associates 2001 New Autoshopper.com Study.

[3]JD Power and Associates 2001 Dealer Satisfaction with Online Buying Services Study.

[4]JD Power and Associates 2001 Dealer E-Mail Responsiveness Study.

[5]L. Jackson, "Web Influence on Automotive Retailing," HoustonChronicle.com, 2001.

[6]Clare Saliba, "European Auto Sites Enjoy Traffic Surge," E-Commerce Times, April 25, 2001.

[7]Marjorie Miller, Los Angeles Times, July 23, 1999.

[8]Brandon Mitchener, "Tax Arbitrage: For a Good Deal on a British Car, You'll Need a Boat," Wall Street Journal, July 19, 1999.

[9]Interview with Dr. Arnold Epstein—same point of view was provided by Melanie Kittrell and Melissa Moncavage.

[10]The Coming Battle for the Hearts and Minds of the Cyberchondriacs, Harris Interactive, February 19, 2001.

[11]Interview with Melissa Moncavage, FDA.

[12]Interview with Ernst Berndt, MIT Sloan.

[13]Merck website http://www.merck.com

[14]Interview with Melanie Kittrell, Merck.

[15]Interview with Dr. Arnold Epstein, Harvard Medical School.

|

EAN: N/A

Pages: 55