9 - Instability and Falls

Editors: Kane, Robert L.; Ouslander, Joseph G.; Abrass, Itamar B.

Title: Essentials of Clinical Geriatrics, 5th Edition

Copyright 2004 McGraw-Hill

> Table of Contents > Part II - Differential Diagnosis and Management > Chapter 8 - Incontinence

function show_scrollbar() {}

Chapter 8

Incontinence

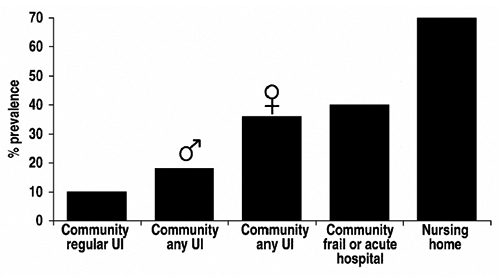

Incontinence is a common, disruptive, and potentially disabling condition in the geriatric population. It is defined as the involuntary loss of urine or stool in sufficient amount or frequency to constitute a social and/or health problem. Figure 8-1 illustrates the prevalence of urinary incontinence. Incontinence is a heterogeneous condition, ranging in severity from occasional episodes of dribbling small amounts of urine to continuous urinary incontinence with concomitant fecal incontinence. Incontinent older persons are not always severely demented, bedridden, or in nursing homes. Many, both in institutions and in the community, are ambulatory and have good mental function.

|

FIGURE 8-1 Prevalence of urinary incontinence in the geriatric population. Regular UI is more often than weekly and/or the use of a pad. |

Approximately 33 percent of women age 65 and above and 15 to 20 percent of men older than 65 years have some degree of urinary incontinence. Between 5 and 10 percent of community-dwelling older adults have incontinence more often than weekly and/or use a pad for protection from urinary accidents. The prevalence is as high as 60 to 80 percent in many long-term care institutions. In both community and institutional settings, incontinence is associated with both impaired mobility and poor cognition.

Physical health, psychological well-being, social status, and the costs of health care can all be adversely affected by incontinence (Table 8-1). Urinary incontinence is curable in many geriatric patients, especially those who have adequate mobility and mental functioning.

TABLE 8-1 POTENTIAL ADVERSE EFFECTS OF URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Even when it is not curable, incontinence can always be managed in a manner that will keep patients comfortable, make life easier for caregivers, and minimize the costs of caring for the condition and its complications. Despite some change in the social perception of incontinence because of television advertisements and public media and educational efforts, many older patients are embarrassed and frustrated by their incontinence and either deny it or do not discuss it with a health professional. It is therefore essential that specific questions about incontinence be included in periodic assessments and that incontinence be noted as a problem when it is detected in institutional settings. Examples of such questions include the following:

Do you have trouble with your bladder?

Do you ever lose urine when you don't want to?

Do you ever wear padding to protect yourself in case you lose urine?

P.174

P.175

This chapter briefly reviews the pathophysiology of geriatric incontinence and provides detailed information on the evaluation and management of this condition. Although most of the chapter focuses on urinary incontinence, much of the pathophysiology also applies to fecal incontinence, which is briefly addressed at the end of the chapter.

NORMAL URINATION

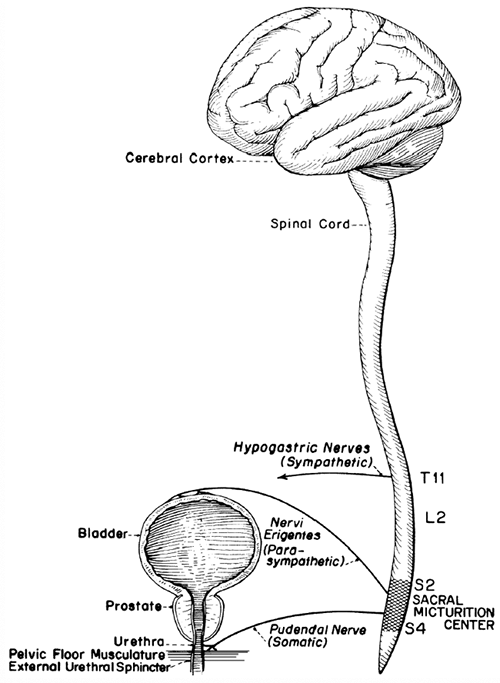

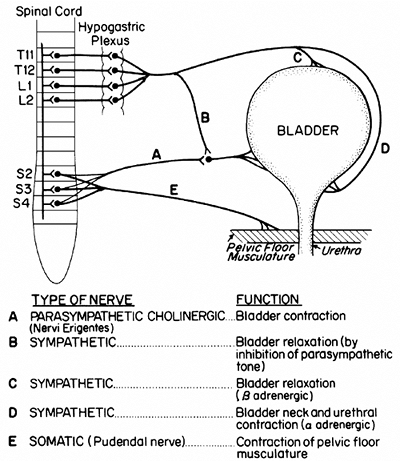

Continence requires effective functioning of the lower urinary tract, adequate cognitive and physical functioning, motivation, and an appropriate environment (Table 8-2). Thus, the pathophysiology of geriatric incontinence can relate to the anatomy and physiology of the lower urinary tract as well as to functional psychological and environmental factors. Several anatomic components participate in normal urination (Fig. 8-2). At the most basic level, urination is governed by reflexes centered in the sacral micturition center. Afferent pathways (via somatic and autonomic nerves) carry information on bladder volume to the spinal cord as the bladder fills. Motor output is adjusted accordingly (Fig. 8-3). Thus, as the

P.176

bladder fills, sympathetic tone closes the bladder neck, relaxes the dome of the bladder, and inhibits parasympathetic tone; somatic innervation maintains tone in the pelvic floor musculature (including striated muscle around the urethra).

TABLE 8-2 REQUIREMENTS FOR CONTINENCE | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

FIGURE 8-2 Structural components of normal micturition. |

|

FIGURE 8-3 Peripheral nerves involved in micturition. |

When urination occurs, sympathetic and somatic tones diminish, and parasympathetic cholinergically mediated impulses cause the bladder to contract. All these processes are under the influence of higher centers in the brainstem, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum. This is a simplified description of a very

P.177

complex process, and the neurophysiology of urination remains incompletely understood. It appears, however, that the cerebral cortex exerts a predominantly inhibitory influence and the brainstem facilitates urination. Thus, loss of the central cortical inhibiting influences over the sacral micturition center from diseases such as dementia, stroke, and parkinsonism can produce incontinence in elderly patients. Disorders of the brainstem and suprasacral spinal cord can interfere with the coordination of bladder contractions and lowering of urethral resistance, and interruptions of the sacral innervation can cause impaired bladder contraction and problems with continence.

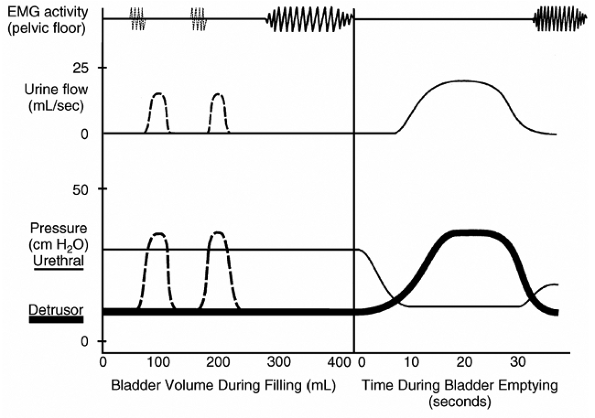

Normal urination is a dynamic process, requiring the coordination of several physiological processes. Figure 8-4 depicts a simplified schematic diagram of the pressure-volume relationships in the lower urinary tract, similar to measurements made in urodynamic studies. Under normal circumstances, as the bladder fills, bladder pressure remains low (e.g., <115 cm H2O). The first urge to void is variable but generally occurs between 150 and 300 mL, and normal

P.178

bladder capacity is 300 to 600 mL. When normal urination is initiated, true detrusor pressure (bladder pressure minus intraabdominal pressure) increases, urethral resistance decreases, and urine flow occurs when detrusor pressure exceeds urethral resistance. If at any time during bladder filling total intravesicular pressure (which includes intraabdominal pressure) exceeds outlet resistance, urinary leakage will occur. This will happen if, for example, intraabdominal pressure rises without a rise in true detrusor pressure when someone with low outlet or urethral sphincter weakness coughs or sneezes. This

P.179

would be defined as genuine stress incontinence in urodynamic terminology. Alternatively, the bladder can contract involuntarily and cause urinary leakage. This would be defined as detrusor motor instability or detrusor hyperreflexia in patients with neurological disorders.

|

FIGURE 8-4 Schematic of the dynamic function of the lower urinary tract during bladder filling (left) and emptying (right). As the bladder fills, true detrusor pressure (thick line at bottom) remains low (less than 5 to 10 cm H2O) and does not exceed urethral resistance pressure (thin line at bottom). As the bladder fills to capacity (generally 300 to 600 mL), pelvic floor and sphincter activity increase as measured by electromyography (EMG, top). Involuntary detrusor contractions (illustrated by dashed lines) occur commonly among incontinent geriatric patients (see text). They may be accompanied by increased EMG activity in attempts to prevent leakage (dashed lines at top). If detrusor pressure exceeds urethral pressure during an involuntary contraction, as shown, urine will flow. During bladder emptying, detrusor pressure rises, urethral pressure falls, and EMG activity ceases in order for normal urine flow to occur. |

CAUSES AND TYPES OF INCONTINENCE

![]() Basic Causes

Basic Causes

There are four basic categories of causes for geriatric urinary incontinence (Fig. 8-5). Determining the cause(s) is essential to proper management.

|

FIGURE 8-5 Basic underlying causes of geriatric urinary incontinence. |

It is very important to distinguish between urological and neurological disorders that cause incontinence and other problems (such as diminished mobility and/or mental function, inaccessible toilets, and psychological problems), which can cause or contribute to the condition. As is the case for a number of other common geriatric problems discussed in this text, multiple disorders often interact to cause urinary incontinence, as depicted in Fig. 8-5.

P.180

Aging alone does not cause urinary incontinence. Several age-related changes can, however, contribute to its development.

In general, with age, bladder capacity declines, residual urine increases, and involuntary bladder contractions become more common (see Fig. 8-4). These contractions are found in up to 80 percent of older incontinent patients, as well as in 5 to 10 percent of older women and in 33 percent or more of older men with no or minimal urinary symptoms. Combined with impaired mobility, these contractions account for a substantial proportion of incontinence in frail geriatric patients.

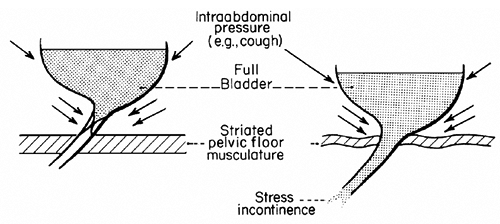

Aging is associated with a decline in bladder outlet and urethral resistance pressure in women. This decline, which is related to diminished estrogen influence and laxity of pelvic structures associated with prior childbirths, surgeries, and deconditioned muscles, predisposes to the development of stress incontinence (Fig. 8-6). Decreased estrogen can also cause atrophic vaginitis and urethritis, which can, in turn, cause symptoms of dysuria and urgency and predispose to the development of urinary infection and urge incontinence. In men, prostatic enlargement is associated with decreased urine flow rates and detrusor motor instability and can lead to urge and/or overflow types of incontinence (see below). Aging is also associated with abnormalities of arginine vasopressin (AVP) levels. Lack of the normal diurnal rhythm of AVP secretion may contribute to nocturnal polyuria, and predispose many older people to nighttime incontinence.

|

FIGURE 8-6 Simplified schematic depicting age-associated changes in pelvic floor muscle, bladder, and urethra-vesicle position, predisposing to stress incontinence. Normally (left), the bladder and outlet remain anatomically inside the intraabdominal cavity, and rises in pressure contribute to bladder outlet closure. Age-associated changes (e.g., estrogen deficiency, surgeries, childbirth) can weaken the structures maintaining bladder position (right); in this situation, increases in intraabdominal pressure can cause urine loss (stress incontinence). |

P.181

![]() Reversible Factors Causing or Contributing to Incontinence

Reversible Factors Causing or Contributing to Incontinence

Numerous potentially reversible conditions and medications may cause or contribute to geriatric incontinence (Tables 8-3 and 8-4).

TABLE 8-3 REVERSIBLE CONDITIONS THAT CAUSE OR CONTRIBUTE TO GERIATRIC URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 8-4 MEDICATIONS THAT CAN AFFECT CONTINENCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The term acute incontinence refers to those situations in which the incontinence is of sudden onset, usually related to an acute illness or an iatrogenic problem, and subsides once the illness or medication problem has been resolved. Persistent incontinence refers to incontinence that is unrelated to an acute illness and persists over time.

P.182

Potentially reversible conditions can play a role in both acute and persistent incontinence. A search for these factors should be undertaken in all incontinent geriatric patients.

The causes of acute and reversible forms of urinary incontinence can be remembered by the acronym DRIP (Table 8-5).

TABLE 8-5 ACRONYM FOR POTENTIALLY REVERSIBLE CONDITIONS* | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

Many older persons, because of urinary frequency and urgency, especially when they are limited in mobility, carefully arrange their schedules (and may even limit social activities) in order to be close to a toilet. Thus, an acute illness (e.g., pneumonia, cardiac decompensation, stroke, lower extremity or vertebral fracture) can precipitate incontinence by disrupting this delicate balance.

Hospitalization, with its attendant environmental barriers (such as bed rails, poorly lit rooms), and the immobility that often accompanies acute illnesses can contribute to acute incontinence. Acute incontinence in these situations is likely to resolve with resolution of the underlying acute illness. Unless an indwelling or external catheter is necessary to record urine output accurately, this type of incontinence should be managed by environmental manipulations, scheduled toiletings,

P.183

P.184

the appropriate use of toilet substitutes (e.g., urinals, bedside commodes) and pads, and careful attention to skin care. In a substantial proportion of patients, incontinence may persist for several weeks after hospitalization and should be evaluated as for persistent incontinence (see below).

Fecal impaction is a common problem in both acutely and chronically ill geriatric patients. Large impactions may cause mechanical obstruction of the bladder outlet in women and may stimulate involuntary bladder contractions induced by sensory input related to rectal distention. Whatever the underlying mechanism, relief of fecal impaction can lead to improvement and sometimes resolution of the urinary incontinence.

Urinary retention with overflow incontinence should be considered in any patient who suddenly develops urinary incontinence. Immobility, anticholinergic and narcotic drugs, and fecal impaction can all precipitate overflow incontinence in geriatric patients. In addition, this condition may be a manifestation of an underlying process causing spinal cord compression and presenting acutely.

Any acute inflammatory condition in the lower urinary tract that causes frequency and urgency can precipitate incontinence. Treatment of an acute cystitis, vaginitis, or urethritis can restore continence.

Conditions that cause polyuria, including hyperglycemia and hypercalcemia, as well as diuretics (especially the rapid-acting loop diuretics), can precipitate acute incontinence. Some older people drink excessive amounts of fluids, and others ingest a large amount of caffeine without understanding the prominent effects it can have on the bladder. Patients with volume-expanded states, such as congestive heart failure and lower extremity venous insufficiency, may have polyuria at night, which can contribute to nocturia and nocturnal incontinence.

As in the case of many other conditions discussed throughout this text, a wide variety of medications can play a role in the development of incontinence in elderly patients via several different mechanisms (see Table 8-4). Whether the incontinence is acute or persistent, the potential role of these medications in causing or contributing to the patients' incontinence should be considered. Whenever feasible, stopping the medication, switching to an alternative, or modifying the dosage schedule can be an important component (and possibly the only one necessary) of the treatment for incontinence.

![]() Persistent Incontinence

Persistent Incontinence

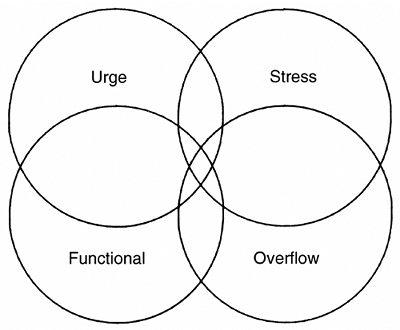

Persistent forms of incontinence can be classified clinically into four basic types. As depicted in Fig. 8-7, these types can overlap. Thus, an individual patient may have more than one type simultaneously. While this classification does not include all the neurophysiological abnormalities associated with incontinence, it is helpful in approaching the clinical assessment and treatment of incontinence in the geriatric population.

|

FIGURE 8-7 Basic types of persistent geriatric urinary incontinence. |

P.185

Three of these types stress, urge, and overflow result from one or a combination of two basic abnormalities in lower genitourinary tract function: (1) Failure to store urine, caused by a hyperactive or poorly compliant bladder or by diminished outflow resistance (2) Failure to empty bladder, caused by a poorly contractile bladder or by increased outflow resistance. Table 8-6 shows the clinical definitions and common causes of persistent urinary incontinence. Stress incontinence is common in older women, especially in ambulatory clinic settings. It may be infrequent and involve very small amounts of urine and need no specific treatment in women who are not bothered by it. On the other hand, it may be so severe and bothersome that it necessitates surgical correction. It is most often associated with weakened supporting tissues and consequent hypermobility of the bladder outlet and urethra caused by lack of estrogen and/or previous vaginal deliveries or surgery (see Fig. 8-6). Obesity and chronic coughing can exacerbate this condition. Women who have had previous vaginal repair and/or surgical bladder neck suspension may develop a weak urethra (intrinsic sphincter deficiency [ISD]). These women generally present with severe incontinence and symptoms of constant wetting with any activity.

TABLE 8-6 BASIC TYPES AND CAUSES OF PERSISTENT URINARY INCONTINENCE | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

This condition should be suspected during office evaluation if a woman loses urine involuntarily with coughing in the supine position during a pelvic examination when her bladder is relatively empty. In general, women with ISD are less responsive to nonsurgical treatment but may benefit from periurethral injections

P.186

P.187

or a surgical sling procedure (see below). Stress incontinence is unusual in men but can occur after transurethral surgery and/or radiation therapy for lower urinary tract malignancy when the anatomic sphincters are damaged.

Urge incontinence can be caused by a variety of lower genitourinary and neurological disorders (see Table 8-6). Patients with urge incontinence typically present with irritative symptoms of an overactive bladder, including frequency (voiding more than every 2 hours), urgency, and nocturia (two or more voids during usual sleeping hours). Urge incontinence is most often, but not always, associated with detrusor motor instability or detrusor hyperreflexia (see Fig. 8-4). Some patients have a poorly compliant bladder without involuntary contractions (e.g., radiation or interstitial cystitis, both relatively unusual conditions).

Other patients have symptoms of an overactive bladder but do not exhibit detrusor motor instability on urodynamic testing. Some patients with neurological disorders have detrusor hyperreflexia on urodynamic testing but do not have urgency and are incontinent without any warning symptoms ( unconscious incontinence ). The above-described patients are generally treated as if they had urge incontinence if they empty their bladders and do not have other correctable genitourinary pathology. A subgroup of older incontinent patients with detrusor motor instability also have impaired bladder contractility emptying less than one-third of their bladder volume with involuntary contractions on urodynamic testing (Resnick and Yalla, 1987; Elbadawi et al., 1993). This condition has been termed detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility (DHIC). Patients with DHIC may present with symptoms that are not typical of urge incontinence and may strain to complete voiding. These patients may be difficult to manage because of their urinary retention.

Urinary retention with overflow incontinence can result from anatomic or neurogenic outflow obstruction, a hypotonic or acontractile bladder, or both. The most common causes include prostatic enlargement, diabetic neuropathic bladder, and urethral stricture. Low spinal cord injury and anatomic obstruction in females (caused by pelvic prolapse and urethral distortion) are less common causes of overflow incontinence. Several types of drugs can also contribute to this type of persistent incontinence (see Table 8-4). Some patients with suprasacral spinal cord lesions (e.g., multiple sclerosis) develop detrusor-sphincter dyssynergy and consequent urinary retention, which must be treated in a similar manner as overflow incontinence; in some instances a sphincterotomy is necessary. The symptoms of overflow incontinence are nonspecific and urinary retention is easily missed on physical examination. Thus, a postvoid residual determination must be performed to exclude this condition.

The term functional incontinence refers to incontinence associated with the inability or lack of motivation to reach a toilet on time. Factors that contribute to functional incontinence (such as inaccessible toilets and psychological disorders) can also exacerbate other types of persistent incontinence. Patients with incontinence that appears to be predominantly related to functional factors may also

P.188

have abnormalities of the lower genitourinary tract. In some patients, it can be very difficult to determine whether the functional factors or the genitourinary factors predominate without a trial of specific types of treatment. However, no matter what specific treatments are prescribed, patients with functional incontinence require systematic toileting assistance as a component of their management plan.

These basic types of incontinence may occur in combination, as depicted by the overlap in Fig. 8-7. Older women commonly have a combination of stress and urge incontinence (generally referred to as mixed incontinence). Frail geriatric patients often have urge incontinence with detrusor instability as well as functional disabilities that contribute to their incontinence.

EVALUATION

![]() Basic Evaluation

Basic Evaluation

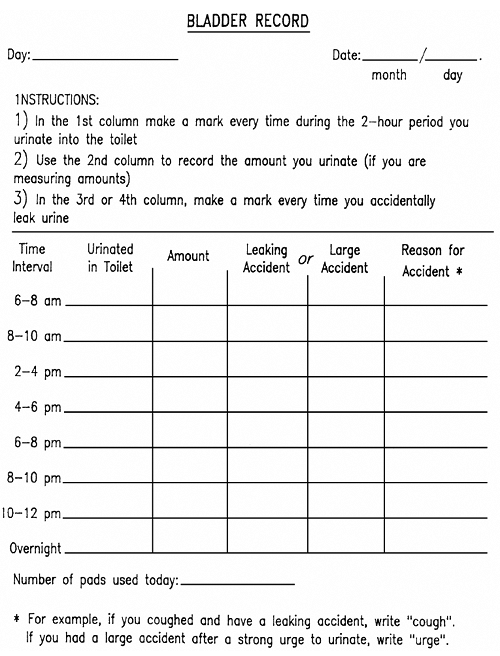

The first step in evaluating incontinent patients is to identify the incontinence by direct observation or the screening questions discussed earlier. In patients with the sudden onset of incontinence (especially when associated with an acute medical condition and hospitalization), the reversible factors that can cause acute incontinence (see Tables 8-3, 8-4, and 8-5) can be ruled out by a brief history, physical examination, postvoid residual determination, and basic laboratory studies (urinalysis, culture, serum glucose or calcium). Table 8-7 shows the basic components of the evaluation of persistent urinary incontinence. Practice guidelines suggest that the basic evaluation should include a focused history, targeted physical examination, urinalysis, and postvoiding residual (PVR) determination (Fantl, Newman, et al., 1996; American Medical Directors Association, 1996). The history should focus on the characteristics of the incontinence, current medical problems and medications, the most bothersome symptom(s), and the impact of the incontinence on the patient and caregivers (Table 8-8). Bladder records or voiding diaries such as those shown in Fig. 8-8 (for outpatients) and Fig. 8-9 (for institutionalized patients) can be helpful in initially characterizing symptoms as well as in following the response to treatment.

TABLE 8-7 COMPONENTS OF THE DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF PERSISTENT URINARY INCONTINENCE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

TABLE 8-8 KEY ASPECTS OF AN INCONTINENT PATIENT'S HISTORY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

FIGURE 8-8 Example of a bladder record for ambulatory care settings. |

|

FIGURE 8-9 Example of a record to monitor bladder and bowel functions in institutional settings. This type of record is especially useful for implementing and following the results of various training procedures and other treatment protocols. (From Ouslander et al., 1986a, with permission.) |

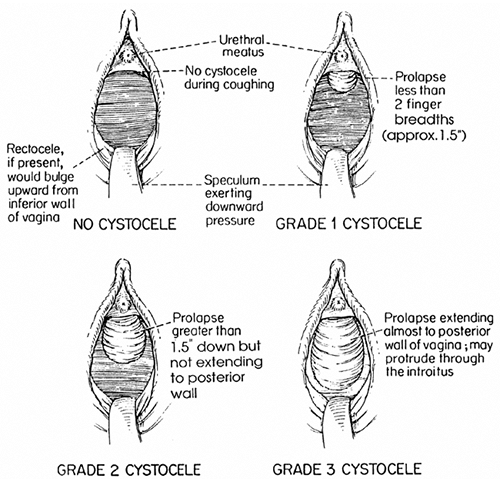

Physical examination should focus on abdominal, rectal, and genital examinations and an evaluation of lumbosacral innervation (Table 8-9). During the history and physical examination, special attention should be given to factors such as mobility, mental status, medications, and accessibility of toilets that may either be causing the incontinence or interacting with urological and neurological disorders to worsen the condition. The pelvic examination in women should include careful inspections of the labia and vagina for signs of inflammation suggestive of atrophic vaginitis and for pelvic prolapse. Most older women have some

P.189

degree of pelvic prolapse (e.g., grade 1 or 2 cystocele as depicted in Fig. 8-10). Not all incontinent older women with these degrees of prolapse need gynecological evaluation (see below).

TABLE 8-9 KEY ASPECTS OF AN INCONTINENT PATIENT'S PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

FIGURE 8-10 Example of a grading system for cystoceles. (From Ouslander et al., 1989a, with permission.) |

A clean urine sample should be collected for urinalysis. For men who are frequently incontinent, making a clean-catch specimen difficult to obtain, a clean specimen can be obtained using a condom catheter after cleaning the penis (Ouslander et al., 1987). For women, a clean specimen can be obtained by

P.190

P.191

cleaning the urethral and perineal area and having the patient void into a disinfected bedpan (Ouslander et al., 1995d). Persistent microscopic hematuria (>5 red blood cells per high-power field) in the absence of infection is an indication for further evaluation to exclude a tumor or other urinary tract pathology.

Because the prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria roughly parallels the prevalence of incontinence, incontinent geriatric patients commonly have significant bacteriuria. In the initial evaluation of incontinent noninstitutionalized patients, especially those in whom the incontinence is new or worsening, otherwise asymptomatic bacteriuria should be treated before further evaluation is undertaken. In the nursing home population, we do not recommend eradicating

P.192

P.193

P.194

bacteriuria unless symptoms of a urinary tract infection are present, because eradicating bacteriuria does not affect the severity of chronic, stable incontinence (Ouslander et al., 1995a). However, the new onset of incontinence, worsening incontinence, unexplained fever, and declines in mental and/or functional status may be the manifestations of a urinary tract infection in this population.

A PVR determination should be done either by catheterization or ultrasonogram to detect urinary retention, which cannot always be detected by physical examination. A portable ultrasonographic device that calculates residual urine is available (Diagnostic Ultrasound, Redmond, WA).

Patients with residual volumes of more than 200 mL should be considered for further evaluation. The need for further evaluation in patients with lesser degrees of retention should be determined on an individual basis, considering the patients' symptoms and the degree to which they complain of straining or are observed to strain with voiding.

P.195

![]() Further Evaluation

Further Evaluation

The need for further evaluation and the specific diagnostic procedures listed in Table 8-7 should be determined on an individual basis. Clinical practice guidelines state that not all incontinent geriatric patients require further evaluation. Patients who have unexplained polyuria should have their blood glucose and calcium levels determined. Patients with significant urinary retention should have renal function tests and be considered for renal ultrasound and urodynamic testing to determine whether obstruction, impaired bladder contractility, or both are present. Persistent microscopic hematuria in the absence of infection is an indication for urine cytology and urological evaluation, including cystoscopy. Even in the absence of hematuria, patients with the recent and sudden onset of irritative urinary symptoms who have risk factors for bladder cancer (heavy smoking, industrial exposure to aniline dyes) should be considered for these evaluations. Women with marked pelvic prolapse (see Fig. 8-10) should be referred for gynecological evaluation.

Complex urodynamic testing is essential to determine the cause(s) of urinary retention and for any older patient for whom surgical intervention is being considered. Simple urodynamic tests, which can be performed without expensive equipment (including observation for straining during voiding, a cough test for stress incontinence with a comfortably full bladder, and simple cystometry) may be helpful in determining the cause(s) of incontinence in settings in which access to complex urodynamic testing is limited.

Table 8-10 summarizes criteria for referral for further evaluation, and Fig. 8-11 summarizes the overall approach to the evaluation of geriatric urinary incontinence.

TABLE 8-10 CRITERIA FOR CONSIDERING REFERRAL OF INCONTINENT PATIENTS FOR UROLOGICAL, GYNECOLOGICAL, OR URODYNAMIC EVALUATION | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

FIGURE 8-11 Algorithm protocol for evaluating incontinence. |

MANAGEMENT

![]() General Principles

General Principles

Several therapeutic modalities can be used in managing incontinent geriatric patients (Table 8-11). Treatment can be especially helpful if specific diagnoses are made and attention is paid to all factors that may be contributing to the incontinence in a given patient. Even when cure is not possible, the comfort and satisfaction of both patients and caregivers can almost always be enhanced.

TABLE 8-11 TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR GERIATRIC URINARY INCONTINENCE | |

|---|---|

|

Special attention should be given to the management of acute incontinence, which is most common among older patients in acute care hospitals. Acute incontinence may be transient if managed appropriately; on the other hand, inappropriate management may lead to a permanent problem. The most common approach to incontinent geriatric patients in acute care hospitals is indwelling catheterization.

P.196

P.197

In some instances, this is justified by the necessity for accurate measurement of urine output during the acute phase of an illness. In many instances, however, it is unnecessary and poses a substantial and unwarranted risk of catheter-induced infection. Although it may be more difficult and time-consuming, making toilets and toilet substitutes accessible and combining this with some form of scheduled toileting is probably a more appropriate approach in patients who do not require indwelling catheterization. Newer launderable or disposable and highly absorbent bed pads and undergarments may also be helpful in managing these patients. These products may be more costly than catheters but probably result in less morbidity (and, therefore, overall cost) in the long run. All of the potential reversible factors that can cause or contribute

P.198

P.199

P.200

to incontinence (see Tables 8-3, 8-4, and 8-5) should be attended to in order to maximize the potential for regaining continence.

Supportive measures are critical in managing all forms of incontinence and should be used in conjunction with other, more specific treatment modalities. A positive attitude, education, environmental manipulations, the appropriate use of toilet substitutes, avoidance of iatrogenic contributions to incontinence, modifications of diuretic and fluid intake patterns, and good skin care are all important.

Specially designed incontinence undergarments and pads can be very helpful in many patients but must be used appropriately. They are now being marketed on television and are readily available in stores. Although they can be effective, several caveats should be noted:

Garments and pads are a nonspecific treatment. They should not be used as the first response to incontinence or before some type of diagnostic evaluation is done.

Many patients are curable if treated with specific therapies, and some have potentially serious factors underlying their incontinence that must be diagnosed and treated.

Pants and pads can interfere with attempts at behavioral intervention and thereby foster dependency.

Many disposable products are relatively expensive and are not covered by Medicare or other insurance.

To a large extent the optimal treatment of persistent incontinence depends on identifying the type(s). Table 8-12 outlines the primary treatments for the basic types of persistent incontinence in the geriatric population. Each treatment modality is briefly discussed below. Behavioral interventions have been well studied in the geriatric population. These interventions are recommended by guidelines as an initial approach to therapy in many patients because they are generally noninvasive and nonspecific (i.e., patients with stress and/or urge incontinence respond equally well) (Fantl et al., 1991; Ouslander et al., 1995a).

TABLE 8-12 PRIMARY TREATMENTS FOR DIFFERENT TYPES OF GERIATRIC URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

![]() Behavioral Interventions

Behavioral Interventions

Many types of behavioral interventions have been described for the management of urinary incontinence. The term bladder training has been used to encompass a wide variety of techniques. It is, however, important to distinguish between procedures that are patient dependent (i.e., necessitate adequate function, learning capability, and motivation of the patient), in which the goal is to restore a normal pattern of voiding and continence, and procedures that are caregiver dependent that can be used for functionally disabled patients, in which the goal is to keep the patient and environment dry. Table 8-13 summarizes behavioral interventions. All the patient-dependent procedures generally involve the patient's

P.201

continuous self-monitoring, using a record such as the one depicted in Fig. 8-8; the caregiver-dependent procedures usually involve a record such as the one shown in Fig. 8-9.

TABLE 8-13 EXAMPLES OF BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS FOR URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises are an essential component of patient-dependent behavioral interventions. These exercises consist of repetitive contractions and relaxations of the pelvic floor muscles.

The exercises may be taught by having the patient interrupt voiding to get a sense of the muscles being used or by having women squeeze the examiner's fingers during a vaginal examination (without doing a Valsalva maneuver, which is the opposite of the intended effect). A randomized trial has documented that many young-old women (mean age in the mid to upper sixties) can be taught these exercises during an office exam and derive significant reductions in incontinence (Burgio et al., 2002).

Many women, however, especially those older than age 75, require biofeedback to help them identify the muscles and practice the exercises. One exercise

P.202

P.203

P.204

is a 10-second squeeze and a 10-second relaxation. Most older women will have to build endurance gradually to this level. Once learned, the exercises should be practiced many times throughout the day (up to 40 exercises per day) and, importantly, should be used in everyday life during situations (e.g., coughing, standing up, hearing running water) that might precipitate incontinence. Vaginal cones (weights) may be useful adjuncts to pelvic muscle exercises in some patients. Electrical stimulation may also be used to help identify and train pelvic muscles. This technique (using a different frequency of stimulation) may also be useful in suppressing the involuntary bladder contractions associated with urge incontinence. Many older patients are reluctant to purchase the devices for a therapeutic trial.

Biofeedback generally involves the use of vaginal (or rectal) pressure or electromyography (EMG) and abdominal muscle EMG recordings to train patients to contract pelvic floor muscles and relax the abdomen. Studies show that these techniques can be very effective for managing both stress and urge incontinence in the geriatric population Numerous software packages are now available to assist with biofeedback training.

Other forms of patient-dependent interventions include bladder training and bladder retraining. Bladder training involves education, pelvic muscle exercises (with or without biofeedback), strategies to manage urgency, and the regular use of bladder records (see Fig. 8-8). Bladder training is highly effective in selected community-dwelling patients, especially.

Table 8-14 provides an example of a bladder retraining protocol. This protocol is applicable to patients who have had indwelling catheterization for monitoring of urinary output during a period of acute illness or for treatment of urinary retention with overflow incontinence. Such catheters should always be removed as soon as possible, and this type of bladder retraining protocol should enable most indwelling catheters to be removed from patients in acute care hospitals as well as some in long-term care settings. A patient who continues to have difficulty voiding after 1 to 2 weeks of bladder retraining should be examined for other potentially reversible causes of voiding difficulties, such as those mentioned in the preceding discussion of acute incontinence. When difficulties persist, a urological referral should be considered in order to rule out correctable lower genitourinary pathology.

TABLE 8-14 EXAMPLE OF A BLADDER RETRAINING PROTOCOL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

The goal of caregiver-dependent interventions is to prevent incontinence episodes rather than to restore normal patterns of voiding and complete continence. Such procedures are effective in reducing incontinence in selected nursing home residents (Ouslander et al., 1995b). In its simplest form, scheduled toileting involves toileting the patient at regular intervals, usually every 2 h during the day and every 4 h during the evening and night. Habit training involves a schedule of toiletings or prompted voidings that is modified according to the patient's pattern of continent voids and incontinence episodes as demonstrated by a monitoring record such as that shown in Fig. 8-9. Adjunctive techniques to prompt

P.205

P.206

voiding (e.g., running tap water, stroking the inner thigh, or suprapubic tapping) and to facilitate complete emptying of the bladder (e.g., bending forward after completion of voiding) may be helpful in some patients. Prompted voiding has been the best-studied of these procedures. Table 8-15 provides an example of a prompted voiding protocol. Up to 40% of incontinent nursing home residents may become essentially dry during the day with a consistent prompted voiding program (Ouslander et al., 1995b). The success of these interventions is largely dependent on the knowledge and motivation of the caregivers who are implementing them, rather than on the physical functional and mental status of the incontinent patient. Targeting of prompted voiding to selected patients after a 3-day trial (see Table 8-15) may enhance its cost-effectiveness. Quality assurance methods, based on principles of industrial statistical quality control, have been shown to be helpful in maintaining the effectiveness of prompted voiding in nursing homes (Schnelle et al., 1995). However, unless adequate staffing, training, and administrative support for the program persist, the effectiveness of prompted voiding will not be maintained.

TABLE 8-15 EXAMPLE OF A PROMPTED VOIDING PROTOCOL FOR A NURSING HOME | |

|---|---|

|

![]() Drug Treatment

Drug Treatment

Table 8-16 lists the drugs used to treat various types of incontinence.

TABLE 8-16 DRUGS USED TO TREAT URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The efficacy of drug treatment has not been as well studied in the geriatric population as it has in younger populations. However, for many patients, especially those with urge or stress incontinence, drug treatment may be very effective. Drug treatment can be prescribed in conjunction with various behavioral interventions. There are few data on the relative efficacy of drug versus behavioral versus combination treatment (Burgio et al., 1998). Treatment decisions should be individualized and will depend in large part on the characteristics and preferences of the patient and the preference of the health care professional.

For urge incontinence, drugs with anticholinergic and relaxant effects on the bladder smooth muscle are used. All of them can have bothersome systemic anticholinergic side effects, especially dry mouth, and they can precipitate urinary retention in some patients.

Men with some degree of outflow obstruction, diabetics, and patients with impaired bladder contractility are at the highest risk for developing urinary retention and should be followed carefully when these drugs are prescribed. Patients with Alzheimer's disease must be followed for the development of drug-induced delirium, which is, however, unusual. The newest bladder relaxant, tolterodine, appears to have an efficacy similar to that of other anticholinergics (Appell, 1997). Tolterodine and oxybutynin are both available in long-acting preparations. Tolterodine has proven efficacy in the geriatric population (Malone-Lee et al., 2001). Some functionally impaired patients may respond to these drugs when they are prescribed in conjunction with prompted voiding (Ouslander et al., 1995c).

P.207

P.208

P.209

P.210

The goal of treatment in these patients may not be to cure the incontinence but to reduce its severity and prevent discomfort and complications.

For stress incontinence, drug treatment involves a combination of an alpha agonist and estrogen. Drug treatment is appropriate for motivated patients who have mild to moderate degrees of stress incontinence, do not have a major anatomic abnormality (e.g., grade 3 cystocele or intrinsic sphincter deficiency), and do not have any contraindications to these drugs. These patients may also respond to concomitant behavioral interventions, as described above. For stress incontinence, estrogen alone is not as effective as it is in combination with an alpha agonist (Fantl, Bump, et al., 1996). Estrogen is also used for the treatment of irritative voiding symptoms and urge incontinence in women with atrophic vaginitis and urethritis. Oral estrogen is probably not as effective as topical estrogen for these symptoms. Vaginal estrogen can be prescribed 5 nights per week for 1 to 2 months initially and then reduced to a maintenance dose of one to three times per week. A vaginal ring that slowly releases estradiol is also available.

Drug treatment for chronic overflow incontinence using a cholinergic agonist or an -adrenergic antagonist is rarely efficacious.

Bethanechol may be helpful when given for a brief period subcutaneously in patients with persistent bladder contractility problems after an overdistension injury, but it is seldom effective when given over the long term orally. -adrenergic blockers may be helpful in relieving symptoms associated with outflow obstruction in some patients but are probably not efficacious for long-term treatment of overflow incontinence. These drugs are, however, effective in treating irritative voiding symptoms associated with urge incontinence in men with benign prostatic enlargement (Lepor et al., 1996).

![]() Surgery

Surgery

Surgery should be considered for older women with stress incontinence that continues to be bothersome after attempts at nonsurgical treatment and in women with a significant degree of pelvic prolapse or ISD. As with many other surgical procedures, patient selection and the experience of the surgeon are critical to success. All women being considered for surgical therapy should have a thorough evaluation, including urodynamic tests, before undergoing the procedure.

Women with mixed stress incontinence and detrusor motor instability may also benefit from surgery, especially if the clinical history and urodynamic findings suggest that stress incontinence is the predominant problem. Many modified techniques of bladder neck suspension can be done with minimal risk and are highly successful in achieving continence over about a 5-year period. Urinary retention can occur after surgery, but it is usually transient and can be managed by a brief period of suprapubic catheterization. Periurethral injection of collagen

P.211

and other materials is now available and may offer patients with ISD an alternative to surgery. Surgical intervention for patients with ISD involves a perivaginal sling procedure rather than bladder neck suspension.

Surgery may be indicated in men in whom incontinence is associated with anatomically and/or urodynamically documented outflow obstruction. Men who have experienced an episode of complete urinary retention are likely to have another episode within a short period of time and should have a prostatic resection, as should men with incontinence associated with a sufficient amount of residual urine to be causing recurrent symptomatic infections or hydronephrosis. The decision about surgery in men who do not meet these criteria must be an individual one, weighing carefully the degree to which the symptoms bother the patient, the potential benefits of surgery (obstructive symptoms often respond better than irritative symptoms), and the risks of surgery, which may be minimal with newer prostate resection techniques. A small number of older patients, especially men who have stress incontinence related to sphincter damage due to previous transurethral surgery, may benefit from the surgical implantation of an artificial urinary sphincter.

![]() Catheters and Catheter Care

Catheters and Catheter Care

Three basic types of catheters and catheterization procedures are used for the management of urinary incontinence: external catheters, intermittent straight catheterization, and chronic indwelling catheterization.

External catheters generally consist of some type of condom connected to a drainage system. Improvements in design and observance of proper procedure and skin care when applying the catheter will decrease the risk of skin irritation as well as the frequency with which the catheter falls off. Patients with external catheters are at increased risk of developing symptomatic infection. External catheters should be used only to manage intractable incontinence in male patients who do not have urinary retention and who are extremely physically dependent. As with incontinence undergarments and padding, these devices should not be used as a matter of convenience, since they may foster dependency.

Intermittent catheterization can help in the management of patients with urinary retention and overflow incontinence because of an acontractile bladder or DHIC. The procedure can be carried out by either the patient or a caregiver and involves straight catheterization two to four times daily, depending on catheter urine volumes and patient tolerance. In general, bladder volume should be kept to less than 400 mL. In the home setting, the catheter should be kept clean (but not necessarily sterile).

Intermittent catheterization may be useful for certain patients in acute care hospitals and nursing homes, for example following removal of an indwelling catheter in a bladder retraining protocol (see Table 8-14). Nursing home residents,

P.212

however, may be difficult to catheterize, and the anatomic abnormalities commonly found in older patients' lower urinary tracts may increase the risk of infection as a consequence of repeated straight catheterizations. In addition, using this technique in an institutional setting (which may have an abundance of organisms that are relatively resistant to many commonly used antimicrobial agents) may yield an unacceptable risk of nosocomial infections, and using sterile catheter trays for these procedures would be very expensive; thus, it may be extremely difficult to implement such a program in a typical nursing home setting.

Chronic indwelling catheterization is overused in some settings and increases the incidence of a number of complications, including chronic bacteriuria, bladder stones, periurethral abscesses, and even bladder cancer. Nursing home residents, especially men, managed by this technique are at relatively high risk of developing symptomatic infections. Given these risks, it seems appropriate to recommend that the use of chronic indwelling catheters be limited to certain specific situations (Table 8-17). When indwelling catheterization is used, certain principles of catheter care should be observed in order to attempt to minimize complications (Table 8-18).

TABLE 8-17 INDICATIONS FOR CHRONIC INDWELLING CATHETER USE | |

|---|---|

|

TABLE 8-18 KEY PRINCIPLES OF CHRONIC INDWELLING CATHETER CARE | |

|---|---|

|

FECAL INCONTINENCE

Fecal incontinence is less common than urinary incontinence. Its occurrence is relatively unusual in older patients who are continent with regard to urine; however, a large proportion (30 to 50 percent) of geriatric patients with frequent urinary incontinence also have episodes of fecal incontinence. This coexistence suggests common pathophysiological mechanisms.

P.213

Defecation, like urination, is a physiological process that involves smooth and striated muscles, central and peripheral innervation, coordination of reflex responses, mental awareness, and physical ability to get to a toilet. Disruption of any of these factors can lead to fecal incontinence. The most common causes of fecal incontinence are problems with constipation and laxative use, neurological disorders, and colorectal disorders (Table 8-19). Constipation is extremely common in the geriatric population and, when chronic, can lead to fecal impaction and incontinence. The hard stool (or scybalum) of fecal impaction irritates the rectum and results in the production of mucus and fluid. This fluid leaks around the mass of impacted stool and precipitates incontinence. Constipation is difficult to define; technically it indicates less than three bowel movements per week, although many patients use the term to describe difficult passage of hard stools or a feeling of incomplete evacuation. Poor

P.214

dietary and toilet habits, immobility, and chronic laxative abuse are the most common causes of constipation in geriatric patients (Table 8-20).

TABLE 8-19 CAUSES OF FECAL INCONTINENCE | |

|---|---|

|

TABLE 8-20 CAUSES OF CONSTIPATION | |

|---|---|

|

Appropriate management of constipation will prevent fecal impaction and resultant fecal incontinence. The first step in managing constipation is the identification of all possible contributory factors. If the constipation is a new complaint and represents a recent change in bowel habit, then colonic disease, endocrine or metabolic disorders, depression, or drug side effects should be considered (see Table 8-19).

Proper diet, including adequate fluid intake and bulk, is important in preventing constipation. Crude fiber in amounts of 4 to 6 g (equivalent to 3 or 4 tablespoons of bran) a day is generally recommended. Improving mobility, body positioning during toileting, and the timing and setting of toileting are all important in managing constipation.

Defecation should optimally take place in a private, unrushed atmosphere and should take advantage of the gastrocolic reflex, which occurs a few minutes after eating. These factors are often overlooked, especially in nursing home settings.

A variety of drugs can be used to treat constipation (Table 8-21). These drugs are often overused; in fact, their overuse may cause an atonic colon and contribute to chronic constipation ( cathartic colon ).

TABLE 8-21 DRUGS USED TO TREAT CONSTIPATION | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Laxative drugs can also contribute to fecal incontinence. Rational use of these drugs necessitates knowing the nature of the constipation and quality of the stool. For example, stool softeners will not help a patient with a large mass of already soft stool in the rectum. These patients would benefit from a glycerin or irritant suppositories.

The use of osmotic and irritant laxatives should be limited to no more than three or four times a week.

Fecal incontinence from neurological disorders is sometimes amenable to biofeedback therapy, although most severely demented patients are unable to

P.215

cooperate. For those patients with end-stage dementia who fail to respond to a regular toileting program and suppositories, a program of alternating constipating agents (if necessary) and laxatives on a routine schedule (such as giving laxatives or enemas three times a week) is often effective in controlling defecation.

Experience suggests that these measures should permit management of even severely demented patients. As a last resort, specially designed incontinence undergarments are sometimes helpful in managing fecal incontinence and preventing complications. Frequent changing is essential, because fecal material, especially in the presence of incontinent urine, can cause skin irritation and predispose to pressure ulcers.

References

American Medical Directors Association: Urinary Incontinence: Clinical Practice Guideline. Columbia, MD, AMDA, 1996.

Appell RA: Clinical efficacy and safety of tolterodine in the treatment of overactive bladder: a pooled analysis. Urology 50(Suppl 6A):90 96, 1997.

Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al: Behavioral vs. drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women. JAMA 280(23):1995 2000, 1998.

P.216

Burgio KL, Goode PS, Locher JL, et al: Behavioral training with and without biofeedback in the treatment of urge incontinence in older women. JAMA 288(18):2293 2299, 2002.

Elbadawi A, Yalla SV, Resnick N: Structural basis of geriatric voiding dysfunction: I. Methods of a prospective ultrastructural/urodynamic study and an overview of the findings. J Urol 150:1650 1656, 1993.

Fantl JA, Wyman FJ, McClish DK, et al: Efficacy of bladder training in older women with urinary incontinence. JAMA 265:609 613, 1991.

Fantl JA, Newman DK, Colling J, et al: Urinary Incontinence in Adults: Acute and Chronic Management. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 2, 1996, Update (AHCPR Publication No. 96 0682). Rockville, MD, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1996a.

Fantl JA, Bump RC, Robinson D, et al: Efficacy of estrogen supplementation in the treatment of urinary incontinence: the Continence Program for Women Research Group. Obstet Gynecol 88:745 749, 1996b.

P.217

Lepor H, Williford WO, Barry MJ, et al: The efficacy of terazosin, finasteride, or both in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study Group. N Engl J Med 335:533 539, 1996.

Malone-Lee JG, Walsh JB, Maugourd MF, et al: Tolterodine: a safe and effective treatment for older patients with overactive bladder. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:700 705, 2001.

Ouslander JG, Uman GC, Urman HN: Development and testing of an incontinence monitoring record. J Am Geriatr Soc 34:83 90, 1986a.

Ouslander JG, Greengold BA, Silverblatt FJ, et al: An accurate method to obtain urine for culture in men with external catheters. Arch Intern Med 147:286 288, 1987.

Ouslander JG, Leach GE, Staskin DR: Simplified tests of lower urinary tract function in the evaluation of geriatric urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc 37:706 714, 1989a.

Ouslander JG, Schapira M, Schnelle J, et al: Does eradicating bacteriuria affect the severity of chronic urinary incontinence among nursing home residents? Ann Intern Med 122:749 754, 1995a.

Ouslander JG, Schnelle JF, Uman G, et al: Predictors of successful prompted voiding among incontinent nursing home residents. JAMA 273:1366 1370, 1995b.

Ouslander JG, Schnelle JF, Uman G, et al: Does oxybutynin add to the effectiveness of prompted voiding for urinary incontinence among nursing home residents? a placebo-controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 43:610 617, 1995c.

Ouslander JG, Schapira M, Schnelle JF: Urine specimen collection from incontinent female nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 43:279 281, 1995d.

Resnick NM, Yalla SV: Detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractile function: an unrecognized but common cause of incontinence in elderly patients. JAMA 257:3076 3081, 1987.

Schnelle JF, McNees P, Crook V, et al: The use of a computer-based model to implement an incontinence management program. Gerontologist 35:656 665, 1995.

Suggested Readings

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A (eds): Incontinence. 2nd International Consultation on Incontinence. Plymouth, United Kingdom, Plybridge Distributors, 2001.

Barry MJ: A 73-year-old man with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. JAMA 287(24):2178 2184, 1997.

Brown JS, Vittinghoff E, Wyman JF, et al: Urinary incontinence: does it increase risk for falls and fractures? J Am Geriatr Soc 48:721 725, 2000.

Ouslander JG (ed): Aging and the lower urinary tract. Am J Med Sci 314(4):214 218, 1997.

Ouslander JG, Maloney C, Grasela TH, et al: Implementation of a nursing home urinary incontinence management program with and without tolterodine. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2:207 214, 2001.

P.218

Ouslander JG, Schnelle JF: Incontinence in the nursing home. Ann Intern Med 122:438 449, 1995.

Resnick NM, Ouslander JG (eds): NIH consensus conference on urinary incontinence in adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 38:263 386, 1990.

Romero Y, Evans JM, Fleming KC, Phillip SF: Constipation and fecal incontinence in the elderly population. Mayo Clin Proc 71:81 92, 1996.

Skelly J, Flint AJ: Urinary incontinence associated with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 42:286 294, 1995.

Yoshimura N, Chancellor MB: Current and future pharmacological treatment for overactive bladder. J Urol 168:1897 1913, 2002.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 23