7 - Diagnosis and Management of Depression

Editors: Kane, Robert L.; Ouslander, Joseph G.; Abrass, Itamar B.

Title: Essentials of Clinical Geriatrics, 5th Edition

Copyright 2004 McGraw-Hill

> Table of Contents > Part II - Differential Diagnosis and Management > Chapter 6 - Confusion: Delirium and Dementia

Chapter 6

Confusion: Delirium and Dementia

The appropriate diagnosis and management of geriatric patients exhibiting symptoms and signs of confusion can make a critical difference to their overall health and ability to function independently. Confusion can be acute in onset, or it can be manifest by slowly progressive cognitive impairment. The major causes of confusion in the geriatric population are delirium and dementia. As more people live into the tenth decade of life, the chance that they will develop some form of dementia increases substantially. Community-based studies report a prevalence of dementia as high as 47 percent among those 85 years of age and older. Prevalence rates are, however, highly dependent on the criteria used to define dementia (Erkinjuntti et al., 1997). Between 25 and 50 percent of older patients admitted to acute care medical and surgical services are delirious on admission, or develop delirium during their hospital stay. In nursing homes, 50 to 80 percent of those older than age 65 years have some degree of cognitive impairment.

Misdiagnosis and inappropriate management of syndromes causing confusion in geriatric patients can cause substantial morbidity among the patients, hardship to their families, and millions of dollars in health care expenditure. This chapter provides a practical framework for diagnosing and managing geriatric patients who demonstrate confusion. We focus on the most common causes of confusion in the geriatric population delirium and dementia although a variety of other disorders can cause confusion.

DEFINING CONFUSION

Imprecise definition of the abnormalities of cognitive function in older patients labeled as confused has led to problems in the diagnosis and management of these patients. Confusion has been defined as a mental state in which reactions to environmental stimuli are inappropriate because the person is bewildered, perplexed, or unable to orientate himself (Stedman's Medical Dictionary, 2000). This type of definition, although descriptive, is too broad and imprecise to be clinically

P.122

useful. Terms such as confused or confused at times are also imprecise. Descriptions such as impairment of mental function or cognitive impairment coupled with careful documentation of the timing and nature of specific abnormalities provide more precise and clinically useful information. Such documentation is best accomplished by means of a thorough mental status examination.

A thorough mental status examination has several basic components that are essential in diagnosing dementia, delirium, or other syndromes (Table 6-1). In evaluating older patients who appear confused, attention should focus on each of these components in a systematic manner. Recording observations in each area is critical to recognizing and evaluating changes over time. Standardized and validated measures of cognitive function such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (see Appendix), and the Time and Change Test (Inouye et al., 1998a) can be helpful screening tools in these assessments, as well as in subsequent monitoring. Several factors may influence performance and interpretation of standard mental status tests, such as prior educational level, primary language other than English, severely impaired hearing, or poor baseline intellectual function. Thus, scores on one or more of these tests should not be used to replace a more comprehensive examination that includes all the components listed in Table 6-1.

TABLE 6-1 KEY ASPECTS OF MENTAL STATUS EXAMINATIONS | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Important information can be gleaned unobtrusively from simply observing and interacting with the patient during the history. Is the patient alert and attentive? Does the patient respond appropriately to questions? How is the patient dressed and groomed? Does the patient repeat himself or herself or give an imprecise medical history, suggesting memory impairment? Orientation, insight, and judgment can sometimes be assessed during the history as well.

P.123

Questions relating to specific areas of cognitive functioning should be introduced in a nonthreatening manner, because many patients with early deficits respond defensively. Each of the three basic components of memory should be tested: immediate recall (e.g., repeating digits), recent memory (e.g., recalling three objects after a few minutes), and remote memory (e.g., ability to give details of early life). Language and other cognitive functions should be carefully evaluated. Is the patient's speech clear? Can the patient read (and understand) and write? Does there seem to be a good general fund of knowledge (e.g., current events)? Other cognitive functions that can be tested easily include the ability to perform simple calculations (one that relates to making change while shopping, for example) and to copy diagrams. The ability to interpret proverbs abstractly and to list the names of animals (12 names in 1 minute is normal) are sensitive indicators of cognitive function and are easy to test.

Judgment and insight can usually be assessed during the examination without asking specific questions, though input from family members or other caregivers can be helpful and sometimes necessary. Any abnormal thought content should also be noted during the examination; bizarre ideas, mood-incongruent thoughts, and delusions (especially paranoid delusions) may be prominent in older patients with cognitive impairment and are important both diagnostically and therapeutically. Observations during the examination may also detect abnormalities of executive control. Executive function involves the planning, sequencing, and executing of goal-directed activities. These functions are critical to the ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living. Screening tests for executive dysfunction, including the EXIT and a Clock-Drawing Test, have been developed and validated (Roman and Royall, 1999). The Clock-Drawing Test can be especially helpful in clinical practice and is performed by asking the patient to draw a clock face with a specific time. Inability to perform this test may be unsuspected and indicate a need for further evaluation.

Throughout the examination, the patient's mood and affect should be assessed. Depression, apathy, emotional liability, agitation, and aggression are common in older patients with cognitive impairment (Lyketsos et al., 2002), and failure to recognize these abnormalities can lead to improper diagnosis and management. In some patients such as those who are very intelligent or poorly educated, or have low intelligence, as well as those in whom depression is suspected more detailed neuropsychological testing by an experienced psychologist is helpful in more precisely defining abnormalities in cognitive function and in differentiating between the many and often interacting underlying causes.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF CONFUSION

The causes of confusion in the geriatric population are myriad. The differential diagnosis in an older patient who presents with confusion includes disorders

P.124

of the brain (e.g., stroke, dementia), a systemic illness presenting atypically (e.g., infection, metabolic disturbance, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure), sensory impairment (e.g., hearing loss), and adverse effects of a variety of drugs or alcohol.

Similar to many other disorders in geriatric patients, confusion often results from multiple interacting processes rather than a single causative factor. Accurate diagnosis depends on specifically defining abnormalities in mental status and cognitive function and on consistent definitions for clinical syndromes. Disorders causing confusion in the geriatric population can be broadly categorized into three groups:

Acute disorders, usually associated with acute illness, drugs, and environmental factors (i.e., delirium).

More slowly progressive impairment of cognitive function as seen in most dementia syndromes.

Impaired cognitive function associated with affective disorders and psychoses.

Old age alone does not cause impairment of cognitive function of sufficient severity to render an individual dysfunctional. Mild, recent memory loss and slowed thinking and reaction time are common. The prognostic and therapeutic implications of mild cognitive impairment are subjects of intensive research. Older patients are often labeled senile because they are unable to answer a question or because they are not given adequate time to respond. Other age-associated disorders such as impaired hearing can also lead to mislabeling an older patient as confused or senile.

Three questions are helpful in making an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause(s) of confusion:

Has the onset of abnormalities been acute (i.e., over a few hours or a few days)?

Are there physical factors (i.e., medical illness, sensory deprivation, drugs) that may contribute to the abnormalities?

Are psychological factors (i.e., depression and/or psychosis) contributing to or complicating the impairments in cognitive function?

These questions focus on identifying treatable conditions, which, when diagnosed and treated, might result in substantially improved cognitive function.

DELIRIUM

Delirium is an acute or subacute alteration in mental status especially common in the geriatric population. The prevalence of delirium in hospitalized geriatric patients is approximately 15 percent on admission (Francis, 1992), and the

P.125

incidence in this setting may be up to one-third (Inouye et al., 1996; Schor et al., 1992). In the past, a variety of labels have been used to describe delirious patients (including acute confusional state, acute brain syndrome, metabolic encephalopathy, and toxic psychosis). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) defines diagnostic criteria for delirium (Table 6-2). The key features of this disorder include the following:

TABLE 6-2 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR DELIRIUM | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

Disturbance of consciousness

Change in cognition not better accounted for by dementia

Symptoms and signs developing over a short period of time (hours to days)

Fluctuation of the symptoms and signs

Evidence that the disturbances are caused by the physiological consequences of a medical condition

The disturbances of consciousness and attention, with the suddenness of onset and the fluctuating cognitive status, are the major features that distinguish delirium from other causes of impaired cognitive function. Delirium is characterized by difficulty in sustaining attention to external and internal stimuli, sensory misperceptions (e.g., illusions), and a fragmented or disordered stream of thought. Disturbances of psychomotor activity (such as restlessness, picking at bedclothes, attempting to get out of bed, sluggishness, drowsiness, and generally decreased psychomotor activity) and emotional disturbances (anxiety, fear, irritability, anger, apathy) are very common in delirious patients. Neurological signs (except

P.126

asterixis) are uncommon in delirium. Many hospitalized patients have delirium on only a single day, but the severity and time course of delirium varies considerably. Many factors predispose geriatric patients to the development of delirium, including impaired sensory functioning and sensory deprivation, sleep deprivation, immobilization, transfer to an unfamiliar environment, and psychosocial stresses such as bereavement.

Among hospitalized geriatric patients, several factors are associated with the development of delirium (Schor et al., 1992; Inouye and Charpentier, 1996), including:

Age greater than 80 years

Male sex

Preexisting dementia

Fracture

Symptomatic infection

Malnutrition

Addition of three or more medications

Use of neuroleptics and narcotics

Use of restraints

Bladder catheters

Rapid recognition of delirium is critical because it is often related to other reversible conditions and its development may be a poor prognostic sign for adverse outcomes including nursing home placement and death (Inouye et al., 1998b). Inouye and colleagues described a strategy to identify delirium, termed the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Inouye et al., 1990). The diagnosis of delirium by the CAM requires the presence of:

Acute onset and fluctuating course and

Inattention and

Disorganized thinking or

Altered level of consciousness

It is also important to differentiate delirium from dementia, because the latter is not immediately life-threatening, and inappropriately labeling a delirious patient as demented may delay the diagnosis of serious and treatable conditions. It is not possible to make the diagnosis of dementia when delirium is present in a patient with previously normal or unknown cognitive function. The diagnosis of dementia must await the treatment of all of the potentially reversible causes of delirium, as discussed below. Table 6-3 shows some of the key clinical features that are helpful in differentiating delirium from dementia. Sundowning is a term that describes an increase in confusion which commonly occurs in geriatric patients, especially those with preexisting dementia, at night. This condition is probably related to sensory deprivation in unfamiliar surroundings (such as the acute care hospital) and patients who sundown may actually meet the criteria for delirium.

TABLE 6-3 KEY FEATURES DIFFERENTIATING DELIRIUM FROM DEMENTIA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

P.127

P.128

A complete list of conditions that can cause delirium in the geriatric population would be too long to be useful in a clinical setting. Table 6-4 lists some of the common causes of this disorder. Several of them deserve further attention. Each geriatric patient who becomes acutely confused should be evaluated to rule out treatable conditions such as metabolic disorders, infections, and causes for decreased cardiac output (i.e., dehydration, acute blood loss, heart failure). Sometimes this workup is unrevealing. Small cortical strokes, which do not produce focal symptoms or signs, can cause delirium. These events may be difficult or impossible to diagnose with certainty, but there should be a high index of suspicion for this diagnosis in certain subgroups of patients especially those with a history of hypertension, previous strokes, transient ischemic attacks, or cardiac arrhythmias. If delirium recurs, a source of emboli should be sought and associated conditions (such as hypertension) should be treated optimally. Fecal impaction and urinary retention, common in geriatric patients (especially those in acute care hospitals),

P.129

can have dramatic effects on cognitive function and may be causes of acute confusion. The response to relief from these conditions can be just as impressive.

TABLE 6-4 COMMON CAUSES OF DELIRIUM IN GERIATRIC PATIENTS | |

|---|---|

|

Drugs are a major cause of acute as well as chronic impairment of cognitive function in older patients (Medical Letter, 2002). Table 6-5 lists commonly prescribed drugs that can cause or contribute to delirium. Every attempt should be made to avoid or discontinue any medication that may be worsening cognitive function in a delirious geriatric patient. Environmental factors, especially rapid changes in location (such as being hospitalized, going on vacation, or entering a nursing home) and sensory deprivation, can precipitate delirium. This is especially true of those with early forms of dementia (see below). Measures such as preparing older patients for changes in location, placing familiar objects in the surroundings, and maximizing sensory input with lighting, clocks, and calendars may help prevent or manage delirium in some patients. A Hospital Elder Life Program has been described that may help prevent delirium, and cognitive and functional decline among high risk older patients in acute hospitals (Inouye et al., 2000). This program incorporates several strategies for identifying potentially reversible causes of delirium and medical behavioral and environmental interventions for patients who develop delirium.

TABLE 6-5 DRUGS THAT CAN CAUSE OR CONTRIBUTE TO DELIRIUM AND DEMENTIA* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

DEMENTIA

Dementia is a clinical syndrome involving a sustained loss of intellectual functions and memory of sufficient severity to cause dysfunction in daily living. Its key features include:

P.130

A gradually progressing course (usually over months to years)

No disturbance of consciousness

Dementia in the geriatric population can be grouped into two broad categories:

Reversible or partially reversible dementias

Nonreversible dementias

![]() Reversible Dementias

Reversible Dementias

While it is especially important to rule out treatable and potentially reversible causes of dementia in individual patients, these dementias account for fewer than 20 percent of all causes of dementia in most series (Costa et al., 1996; Clarfield, 1988). Moreover, finding a reversible cause does not guarantee that the dementia will improve after the putative cause has been treated.

Table 6-6 lists causes of reversible dementia. These disorders can be detected by careful history, physical examination, and selected laboratory studies. Drugs known to cause abnormalities in cognitive function (see Table 6-5) should be discontinued whenever feasible. There should be a high index of suspicion regarding excessive alcohol intake in older patients. The incidence of alcohol consumption varies considerably in different populations but is easily missed and can cause dementia as well as delirium, depression, falls, and other medical complications.

TABLE 6-6 CAUSES OF POTENTIALLY REVERSIBLE DEMENTIAS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

One particular disorder, depressive pseudodementia, deserves special emphasis. This term has been used to refer to patients who have reversible or partially

P.131

reversible impairments of cognitive function caused by depression. Depression may coexist with dementia in more than one-third of outpatients with dementia, and in an even greater proportion in nursing homes. The interrelationship between depression and dementia is complex. Many patients with early forms of dementia become depressed. Sorting out how much of the cognitive impairment is caused by depression and how much by an organic factor(s) can be difficult. Some clinical characteristics can be helpful in diagnosing depressive pseudodementia, including prominent complaints of memory loss, patchy and inconsistent cognitive deficits on exam, and frequent don't know answers. Detailed neuropsychological testing, performed by a psychologist or other health care professional skilled in the use of these tools, can be helpful in many patients. At times, even after a complete assessment, uncertainty still exists regarding the role of depression in producing intellectual deficits. Under these circumstances, a careful trial of antidepressants (in rare instances, electroconvulsive therapy) is justified to facilitate the diagnosis and may help improve overall (but not cognitive) functioning. Older patients who develop reversible cognitive impairment while depressed appear at relatively high risk for developing dementia over the following few years, and their cognitive function should be followed closely over time.

![]() Nonreversible Dementias

Nonreversible Dementias

Several different classifications have been recommended for the nonreversible dementias. The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) guideline on Alzheimer's and related dementias (Costa et al., 1996) lists four basic categories, based on the work of Katzman et al. (1988) (Table 6-7):

TABLE 6-7 CAUSES OF NONREVERSIBLE DEMENTIAS | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Degenerative diseases of the central nervous system

Vascular disorders

Trauma

Infections

Alzheimer's disease, other degenerative disorders, and vascular dementias account for a vast majority of dementias in the geriatric population, and are the focus of discussion in this chapter.

Alzheimer's and Other Degenerative Diseases Alzheimer's disease accounts for close to two-thirds of dementias in the geriatric population. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) accounts for up to 25 percent of dementias in some series, and may overlap with Alzheimer's and Parkinson's dementia (Small et al., 1997; McKeith et al., 1996). In addition to the characteristic pathological findings, DLB is characterized by

Detailed visual hallucinations

Parkinsonian signs

Alterations of alertness and attention

P.132

Table 6-8 lists the diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease (AD). Family history and increasing age are the primary risk factors for AD. Approximately 6 to 8 percent of persons older than age 65 have AD. The prevalence doubles every 5 years, so that nearly 30 percent of the population older than age 85 has AD. By the age of 90, almost 50 percent of persons with a first-degree relative suffering from AD might develop the disease themselves. Rare genetic mutations on chromosomes 1, 14, and 21 cause early onset familial forms of AD, and some forms of late-onset AD are linked to chromosome 12 (Small et al., 1997). The strongest genetic linkage with late-onset AD identified thus far is the apolipoprotein E epsilon-4 (APOE-E4) allele on chromosome 19.

TABLE 6-8 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR ALZHEIMER'S DEMENTIA | ||

|---|---|---|

|

P.133

The relative risk of AD associated with one or more copies of this allele in whites is approximately 2.5. However, APOE-E4 does not appear to confer increased risk for AD among African Americans or Hispanics. One study suggests, however, that the cumulative risks of AD to age 90 in the general population, adjusted for education and sex, are four times higher for African Americans and two times higher for Hispanics than for whites (Tang et al., 1998). Because the presence of one or more APOE-E4 alleles is neither sensitive nor specific, there is disagreement on recommending it as a screening test for AD (Small et al., 1997; Mayeux et al., 1998). Until more sensitive and specific tests become available, routine screening, even among high-risk populations, is generally not recommended.

P.134

Other possible risk factors for AD include previous head injury, female sex, lower education level, and other yet-to-be-identified susceptibility genes. Possible protective factors include the use of estrogen, antioxidants, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. The clinical significance of these possible protective effects, however, remains to be proven.

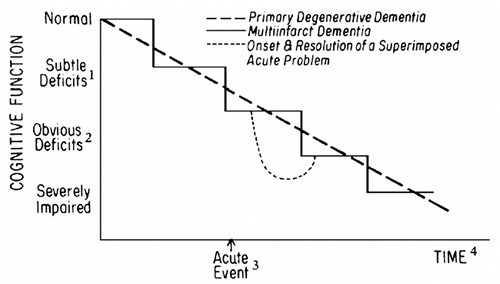

Vascular Dementias Vascular dementias, predominately caused by multiple infarcts (multiinfarct dementia), account for approximately 15 percent of dementia in the geriatric population. Multiinfarct dementia can occur alone or in combination with other disorders that cause dementia. Autopsy studies suggest that cerebrovascular disease may play an important role in the presence and severity of symptoms of AD (Snowdon et al., 1997). Multiinfarct dementia results when a patient has sustained recurrent cortical or subcortical strokes. Many of these strokes are too small to cause permanent or residual focal neurological deficits or evidence of strokes on computed tomography (CT). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be more sensitive in detecting small infarcts, but there has been a tendency to overinterpret some of these findings as more MRI scans are being done. Table 6-9 identifies characteristics of patients likely to have multiinfarct dementia and compares the clinical characteristics of primary degenerative and multiinfarct dementias. A key feature of multiinfarct dementia is the stepwise deterioration in cognitive functioning, as illustrated in Fig. 6-1. Another form of vascular form of dementia has been described, termed senile dementia of the Binswanger type, which may be impossible to differentiate clinically from multiinfarct dementia. It has become increasingly important to differentiate vascular from other dementias because patients with the former may benefit from more aggressive treatment of hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors (Forette et al., 2002; Murray et al., 2002), whereas new pharmacological treatments for AD may not help patients with vascular forms of dementias.

TABLE 6-9 ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE VERSUS MULTIINFARCT DEMENTIA: COMPARISON OF CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

FIGURE 6-1 Primary degenerative dementia versus multiinfarct dementia: comparison of time courses. 1 Recognized by patient, but only detectable on detailed testing. 2 Deficits recognized by family and friends. 3 See text for explanation. 4 Exact time courses are variable; see text. |

EVALUATION

The AHCPR practice guideline (Costa et al., 1996) and a consensus statement of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer's Association, and the American Geriatrics Society (Small et al., 1997) have updated recommendations for the evaluation of patients suspected of having a dementia syndrome. The first step is to recognize clues that dementia may be present. Table 6-10 lists symptoms that should suggest further evaluation. Patients suspected of having dementia should undergo the following:

TABLE 6-10 SYMPTOMS THAT MAY INDICATE DEMENTIA | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Focused history and physical examination, including assessment for delirium and depression and identification of comorbid conditions (e.g., sensory impairment, physical disability)

A functional status assessment (see Chap. 3)

A mental status examination (see above and Table 6-1)

Selected laboratory studies to rule out reversible dementia and delirium

P.135

P.136

Table 6-11 outlines key aspects of the history. Because many physical illnesses and drugs can cause cognitive dysfunction, active medical problems and use of prescription and nonprescription drugs (including alcohol) should be reviewed. The nature and severity of the symptoms should be characterized. What are the deficits? Does the patient admit to them or is the family member describing them? How is the patient reacting to the problems? The responses to these questions can be helpful in differentiating between dementia and depressive pseudodementia. The onset of symptoms and the rate of progression are particularly important. The sudden onset of cognitive impairment (over a few days) should prompt a search for one of the underlying causes of delirium listed in Table 6-4. Irregular, stepwise decrements in cognitive function (as opposed to a more even and gradual loss) favor a diagnosis of multiinfarct dementia (see Table 6-9 and Fig. 6-1). Patients with dementia are often brought for evaluation at a time of sudden worsening of cognitive function (as illustrated by the broken line in Fig. 6-1) and may even meet the criteria for delirium. These sudden changes may be triggered by a number of acute events (a small stroke without focal signs, acute physical illness, drugs, changes in environment, or personal loss such as the death or departure of a relative). Only a careful history (or familiarity with the patient) will

P.137

help to determine when an acute event has been superimposed on a preexisting dementia. Appropriate management of the acute event will, in many instances, result in improvement in cognitive function (see Fig. 6-1, broken line).

TABLE 6-11 EVALUATING DEMENTIA: THE HISTORY | |

|---|---|

|

The history should also include specific questions about common problems requiring special attention in patients with dementia. These problems may include wandering, dangerous driving and car crashes, disruptive behavior (e.g., verbal agitation, physical aggression, and nighttime agitation), delusions or hallucinations, insomnia, poor hygiene, malnutrition, and incontinence. They require careful management and most often substantial involvement of family or other caregivers.

A social history is especially important in patients with dementia. Living arrangements and social supports should be assessed. Along with functional status, these factors play a major role in the management of patients with dementia and are of critical importance in determining the necessity for institutionalization. A patient with dementia and weak social supports may require institutionalization at a higher level of function than will a patient with strong social supports. In addition to the lack of availability of a spouse, child, or other relative who can

P.138

serve as a caregiver, the caregiver's employment and/or poor health can play an important role in determining the need for institutional care.

A general physical examination should focus particularly on cardiovascular and neurological assessment. Hypertension and other cardiovascular findings and focal neurological signs (such as unilateral weakness or sensory deficit, hemianopsia, Babinski reflex) favor a diagnosis of multiinfarct dementia. Pathological reflexes (such as the glabellar sign and grasp, snout, and palmomental reflexes) are nonspecific and occur in many forms of dementia as well as in a small proportion of normal aged persons. These frontal lobe release signs as well as impaired stereognosis or graphesthesia, gait disorder, and abnormalities on cerebellar

P.139

testing are significantly more common in patients with Alzheimer's disease than in age-matched controls. Parkinsonian signs (tremor, bradykinesia, muscle rigidity) should be sought because they may indicate either dementia associated with Lewy bodies or frank Parkinson's disease.

A careful mental status examination (see Table 6-1) and a standardized mental status test should be performed. Although practice guidelines indicate that no single test is clearly superior, the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Time and Change Test are rapid tests that can be used in clinical practice (see Appendix). Neuropsychological testing can be helpful when there is a normal mental status score but also functional and/or behavioral changes (this can occur in patients with high baseline intelligence) or when there is a low score without functional deficits (this can occur in patients with lower educational levels). Neuropsychological testing can also be helpful in differentiating depression and dementia and in pinpointing specific cognitive strengths and weaknesses for patients, families, and health providers.

Selected diagnostic studies are useful in ruling out reversible forms of dementia (Table 6-12). Although CT and MRI scans of the head are expensive, many clinicians and experts order one of these tests for patients with dementia of recent onset in whom no other clinical findings explain the dementia and in those with focal neurological signs or symptoms. Cerebral atrophy on one of these scans

P.140

does not establish the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease; it can occur with normal aging as well as with several specific disease processes. The scan is thus recommended to rule out treatable causes (e.g., subdural hematoma, tumors, normal-pressure hydrocephalus). CT and MRI each have advantages and disadvantages. They are roughly equivalent in the detection of most remediable structural lesions. MRI will demonstrate more lesions than CT in patients with multiinfarct dementia, but will also demonstrate white matter changes of uncertain clinical significance (Small et al., 1997). Position emission tomography (PET) scanning is increasingly available, but remains largely a research tool. PET scanning quantitates glucose metabolism and reveals decreases in specific areas (e.g., frontotemporal) that are highly associated with Alzheimer's disease. PET scan abnormalities can precede the development of clinical deficits by several years in patients at risk for Alzheimer's disease.

TABLE 6-12 EVALUATING DEMENTIA: RECOMMENDED DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES | |

|---|---|

|

MANAGEMENT OF DEMENTIA

![]() General Principles

General Principles

Although complete cure is not available for the vast majority of dementias, optimal management can provide improvements in the ability of these patients to function, as well as in their overall well-being and that of their families and other caregivers. Table 6-13 outlines key principles for the management of dementia.

TABLE 6-13 KEY PRINCIPLES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF DEMENTIA | |

|---|---|

|

If causes of reversible or partially reversible forms of dementia are identified (see Table 6-6), they should be specifically treated. Small strokes (lacunar infarcts), which can cause further deterioration of cognitive function in patients with AD, as well as those with vascular dementia, may be prevented by controlling hypertension; thus hypertension should be aggressively treated in patients with dementia as long as side effects can be avoided. Other specific diseases such as Parkinson's disease should be optimally managed. The treatment of these and other medical conditions is especially challenging because treatment (usually drugs) may have adverse effects on cognitive function.

![]() Pharmacological Treatment of Dementia

Pharmacological Treatment of Dementia

There are three basic approaches to the pharmacological treatment of dementia:

Agents that enhance cognition and function

Drug treatment of coexisting depression

Pharmacological treatment of complications such as paranoia, delusions, psychoses, and agitation (verbal and physical)

P.141

P.142

Drug treatment of depression is discussed in detail in Chap. 7. Pharmacological treatments including antipsychotics and sedatives are discussed in Chap. 14.

The primary pharmacological approach to the treatment of AD has been the use of cholinesterase inhibitors. Some evidence suggests that these drugs are also effective for DLB and multiinfarct dementia. There are four approved drugs of this class on the market (tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine). Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials suggest that these drugs can have clinically important positive effects on cognitive function, and may improve or prevent decline in overall function and potentially delay nursing home admission. Tacrine is potentially hepatotoxic, and is generally not prescribed for this reason. No studies have compared the other three drugs in this class to each other. Gastrointestinal side effects can be problematic and include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. On the other hand, the benefits of these drugs include slight improvements in cognitive function (e.g., generally less than 3 points on a Mini-Mental State Exam), improvements in behavior, and a substantial several month delay in the progression of cognitive impairment and the development of related behavioral symptoms.

Other drugs, including estrogen (in women), vitamin E, ginkgo biloba, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, are commonly used to prevent dementia. There is, however, no evidence that these drugs are effective in preventing or treating dementia (most evidence suggests they are not). The role of these agents in preventing dementia is under active investigation. Many geropsychiatrists and geroneurologists do prescribe vitamin E in addition to a cholinesterase inhibitor for patients with new onset and early dementia.

![]() Nonpharmacological Management

Nonpharmacological Management

A variety of supportive measures and other nonpharmacological management techniques are useful in improving the overall function and well-being of patients with dementia and their families (see Table 6-13). These interventions range from specific recommendations for caregivers, such as alterations in the physical environment, the use of memory aids, the avoidance of stressful tasks, and preparation for the patient's move to another living setting with a higher level of care, to more general techniques, such as providing information and counseling services. Many nursing homes have developed special care units for dementia patients. With few exceptions, however (Rovner et al., 1996), there is little evidence that such units improve outcomes (Phillips et al., 1997). Assisted-living facilities are now establishing specialized dementia units, with optimally designed environments, trained staff, and intensive activities programming, and without the more hospital-like environment typical of many nursing homes.

P.143

The provision of ongoing care is especially important in the management of dementia patients. Reassessment of the patient's cognitive abilities can be helpful in identifying potentially reversible causes for deteriorating function and in making specific recommendations to family and other caregivers. The family is the primary target of strategies to help manage dementia patients in noninstitutional settings. Caring for relatives with dementia is physically, emotionally, and financially stressful. Information on the disease itself and the extent of impairment and on community resources helpful in managing these patients can be of critical importance to family and caregivers. The local chapter of the Alzheimer's Association and the Area Agency on Aging are examples of community resources that can provide education and linkages with appropriate services. Anticipating and teaching family members strategies to cope with common behavioral problems associated with dementia such as wandering, incontinence, day night reversal, and nighttime agitation can be of critical importance. Hazardous driving that can result in car crashes is an especially troublesome problem. Several states now require reporting patients with dementia who maintain drivers' licenses. There remain, however, no validated methods of assessing driving capabilities and safety among individuals with early dementia. Wandering may be especially hazardous for the dementia patient's safety and is associated with falls. Incontinence is common and often very difficult for families to manage (see Chap. 8). Books providing information and suggestions for family management techniques are very useful (see Suggested Readings). Support groups for families of patients with Alzheimer's disease through the Alzheimer's Association are available in most large cities. Family counseling can be helpful in dealing with a variety of issues such as anger, guilt, decisions on institutionalization, handling the patient's assets, and terminal care. Dementia patients and their families should also be encouraged to discuss and document their wishes, using a durable power of attorney for health care or an equivalent mechanism early in the course of the illness (see Chap. 17). Family members should be encouraged to seek respite care periodically to provide time for themselves. Some communities have formal respite care programs available. In the absence of such programs, informal arrangements can often be made to relieve the primary family caregivers for short periods of time at regular intervals. Such relief will help the caregiver to cope with what is generally a very stressful situation. Often a multidisciplinary group of health professionals made up of a physician, a nurse, a social worker, and, when needed, rehabilitation therapists, a lawyer, and a clergy member must coordinate efforts to manage these patients and provide support to family and caregivers.

References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision. Washington, DC, APA, 2000.

P.144

Clarfield AM: The reversible dementias: do they reverse? Ann Intern Med 109:476 186, 1988.

Costa PT Jr, Williams TF, Somerfield M, et al: Recognition and Initial Assessment of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 19. Rockville, MD, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR Publication No. 97 0702. November 1996.

Erkinjuntti T, Ostbye T, Steenhuis R, et al: The effect of different diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of dementia. N Engl J Med 337:1667 1674, 1997.

Forette F, Seux M-L, Staessen JA, et al: The prevention of dementia with antihypertensive treatment. Arch Intern Med 162:2046 2052, 2002.

Francis J: Delirium in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 40:829 838, 1992.

Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM: The hospital elder life program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 48:1697 1706, 2000.

Inouye SK, Charpentier PA: Precipitating factors of delirium in hospitalized elderly persons: predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA 275:852 857, 1996.

Inouye SK, Robison JT, Froehlich TE, Richardson ED: The time and change test: a simple screening test for dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 53A(4):M281 M286, 1998a.

Inouye SK, Rushing JT, Foreman MD, Palmer RM, Pompei P: Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? J Gen Intern Med 13:234 242, 1998b.

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al: Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 113:941 948, 1990.

Katzman R, Lasker B, Bernstein N: Advances in the diagnosis of dementia: accuracy of diagnosis and consequences of misdiagnosis of disorders causing dementia, in Terry RD (ed): Aging and the Brain, 17 62. New York, Raven Press, 1988.

Lipowski ZJ: Delirium (acute confusional states). JAMA 258:1789 1792, 1987.

Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al: Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. JAMA 288(12):1475 1483, 2002.

Mayeux R, Saunders AM, Shea S, et al: Utility of the apolipoprotein E genotype in the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 338:506 511, 1998.

McKeith LG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al: Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report on the consortium of DLB international workshop. Neurology 47:1113 1124, 1996.

Medical Letter: Drugs that may cause psychiatric symptoms. Med Lett 44(1134):59 62, 2002.

Murray MD, Lane KA, Gao S, et al: Preservation of cognitive function with antihypertensive medications. Arch Intern Med 162:2090 2096, 2002.

Phillips C, Sloane P, Hawes C, et al: Effects of residence in Alzheimer disease special care units on functional outcomes. JAMA 278:1340 1344, 1997.

Roman GC, Royall DR: Executive control function: a rational basis for the diagnosis of vascular dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 13:S69 S80, 1999.

P.145

Rovner BW, Steele CD, Shmuely Y, Folstein MF: A randomized trial of dementia care in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 44:7 13, 1996.

Schor JD, Levkoff SE, Lipsitz LA, et al: Risk factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA 267:827 831, 1992.

Small GW, Rabins PV, Barry PP, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. JAMA 278:1363 1371, 1997.

Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, et al: Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer's disease: the nun study. JAMA 277:813 817, 1997.

Stedman's Medical Dictionary, New York, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.

Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, et al: The ApoE-E4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA 279:751 755, 1998.

Suggested Readings

Cohen-Mansfield J: Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 9:361 381, 2001.

Geldmacher DS, Whitehouse PJ: Evaluation of dementia. N Engl J Med 335:330 336, 1996.

Gomez-Tortosa E, Ingraham AO, Irizarry MC, Hyman BT: Dementia with Lewy bodies. J Am Geriatr Soc 46:1449 1458, 1998.

Mace NL (ed): Dementia care: patient, family and community. Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990.

Martin JB: Molecular basis of the neurodegenerative disorders. N Engl J Med 340(25):1970 1980, 1999.

Mayeux R, Sano M: Treatment of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 341(22):1670 1679, 1999.

Silverman DHS, Small GW, Chang CY, et al: Positron emission tomography in evaluation of dementia: regional brain metabolism and long-term outcome. JAMA 286(17):2120 2127, 2001.

Williams ME: The American Geriatrics Society's Complete Guide to Aging and Health. New York, American Geriatrics Society, 1995.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 23