Selected Implications

|

Most organizations will, in the near future, feel their way around in the e-commerce domain. At the same time, they will jockey for position in the e- as well as the real market space. This is also a period when forays into e-commerce initiatives will imply changes to how organizations work and inter-work. The core issue that will determine the success of any e-commerce strategy is the creation of inimitable value. From a value perspective, we discuss two such themes that are important to strategy development. They are governance frameworks across organizations and the need to balance power and trust in the context of e-commerce.

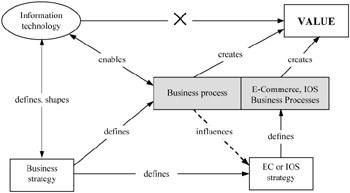

According to Hagel and Brown (2001), the role of the CIO is going to change into an even more entrepreneurial and strategizing one. In other words, CIOs, who are already involved with strategic issues, will find themselves dealing with issues that require couplings between technologies and businesses or between diverse business entities. CIOs who have been mote technology-focused will find themselves having to pay increased attention to issues within and outside their own businesses. It is easy to see from Figure 2 that the CIO will be the steward of not only IS strategy but also that of the e-commerce strategy. This implies that the CIO needs to be coupled closely to the organizational strategy too.

Figure 2: The Role of IOS and E-Commerce.

In addition, a shift to web services architecture would imply that organizations would end up outsourcing more IT functions (as they get standardized) and yet concentrate to develop new and inimitable capabilities (see Case 2). In many ways, this is what Cisco achieved when it seamlessly integrated internal and external information systems based on the Internet protocols and a browser front-end.

Hagel and Brown (2001) also discuss how CIOs will become knowledge brokers (putting together expertise from within and outside their organizations), relationship managers (coordinating the efforts of an array of organizations) and negotiators (necessitating and enabling a shift in leadership style from command-and-control to persuade-and-influence).

Case 3. Changing Roles of an Exchange (Koch, 2001)

For some companies—most notably small suppliers—even the basic software promised by the more ambitious public exchanges is better than what they use now: a phone and a fax. In the food industry, where Schult estimates that 95 percent of supply chain transactions are still done manually, small suppliers can afford to consider renting supply chain software if it means their only infrastructure investment is a PC and a Web browser. It's a possibility that Cargill's planners hadn't counted on when they first plotted the company's e-commerce strategy in 1999. "Originally we thought exchange members would need to be responsible for their own back office," says Geisler. "Now Novopoint has smaller companies asking if they can sign up for its architecture on an ASP [application service provider] basis." Offering software for rent to small companies in the food industry will serve two major purposes for Novopoint. It will expand membership and provide a much-needed revenue stream for the exchange. "We're going from being an exchange to becoming an outsourcer of supply chain visibility and collaboration," says Geisler. There's evidence that waiting for exchange technology to become more real before jumping in will backfire. Public exchanges are making decisions now about how they'll operate, what communications standards they'll use and what functionality they'll offer. Most exchange builders want to be part of those decisions, rather than on the outside looking in. Those who have taken the leap into public exchanges are also discovering the impact they will have on their internal businesses. As Cargill is discovering, the public exchange has the potential to disrupt everything it does, from the way it goes to market to its internal e-commerce efforts. The first realization Cargill had was that Novopoint could become a potential outsourcer for Cargill's internal electronic commerce efforts. "As soon as Novopoint came along, our extranet ceased to have competitive advantage for us," says Geisler. Novopoint has also put pressure on Cargill's business side to figure out how it will remold its businesses to link to customers online. "It keeps us on our toes; but it puts a lot of pressure on our businesses to adapt," says Geisler.

Case 3 demonstrates the organic emergence and unfolding of e-commerce strategy whereby an organization that started as a portal, had to assume the role of an ASP and finally expand roles to enable collaboration and trust. In other words, relating case C to Figure 2, we see that the value propositions for different players emerge over time as new understandings about the technology emerge and as the providers and consumers of e-services begin to develop relationships. For instance, Cargill is as affected by Novopoint, as smaller players with which Cargill interacts via Novopoint.

Of particular interest to us is the case of inter-organizational governance as it applies to the area of information systems. This is going to become increasingly important since, instead of hierarchical planning, task execution and control, interfirm relationship management is based on consensus, agreements, negotiations and understanding among the people involved. While the CIO's area of influence is originally restricted to a specific organization, the CIO's success and internal evaluation may be based on the success of interfirm relationships. Therefore, while the CIO may not be able to manage the relationship, s/he has to ensure the success of the e-commerce systems. Case 4 describes a specific case of such inter-organizational issues.

Case 4. A CIO's Dilemma

Kelly Knepley is trapped in the middle of a battle for his company's information. It's a fight that pits big auto manufacturers such as DaimlerChrysler, Ford and GM against the so-called tier-one suppliers, such as Dana and Johnson Controls. The issue: Both want to control the flow of supply chain information at smaller tier-two suppliers such as Knepley's company, Hayes-Lemmerz. The battle could be worth billions. In an industry that makes some of the most complex products in the world, improving the electronic flow of information—about processes such as inventory, manufacturing schedules, product design and procurement—could shave at least 6 percent off the cost of building a car, according to industry analysts. So it's not surprising that manufacturers are ganging up to control that vital and valuable data pipeline through Covisint, the online exchange owned jointly by the top manufacturers. But big suppliers aren't buying in to the Covisint vision. Instead, they're gearing up their own e-commerce exchanges, designed to control their burgeoning supply chains. Neither effort will be successful without the support of people like Knepley. As the director of IT for the suspension and power train business units of his company, Knepley manages the information links between Hayes-Lemmerz and its biggest customers. Right now, he tends a garden of laughably redundant, expensive computer systems that have sprung up during the past 20 years in response to his customers' demands to share supply chain information. Ford requires all its suppliers to use one system, DaimlerChrysler requires its suppliers to use another and so on. Knepley estimates that he uses the manpower of at least one-half an IT staffer at each of Hayes-Lemmerz's 22 manufacturing plants just to manage these different systems—at a yearly maintenance cost of about $500,000. He'd like to dig the garden up and replace it with a single electronic tree that connects him with all of his customers.

This brings us to the last component of the importance of managing interfaces in the development of e-commerce strategies. Trust is the ultimate frontier that needs to be crossed to actualize the potential of collaborative e-commerce strategies [10]. So far researchers have "not identified even one public company in an existing traditional tangible goods supply chain that has opted to open an electronic channel directly to its end users." Barros et al. (1998) also agree that the largest untapped opportunity in electronic commerce will go to the value chains that adopt the electronic business model that aligns the strategic sources of value of the distributor/retailer with the manufacturer and supplier while eliminating the inefficient transaction costs. Until such alignment takes place (involving interfirm process creation and re-engineering), marginal savings will be achieved instead of order of magnitude strategic improvements.

Case 5. Building Trust (Koch, 2001)

Companies in every major industry are making devil pacts with their fiercest competitors and staking out the best 40 acres they can find online to begin building their industry's monster hub for e-business. Getting arch competitors to agree on anything will be a tall order. Convincing suppliers to believe that exchanges are meant to do anything but beat them down on prices is another challenge. Building software specific enough to serve member and supplier needs while keeping the software simple enough for everyone to use will be an unprecedented feat. No one, not even Wal-Mart, has done that yet. Still, the difficulty of exchange building hasn't kept industry heavyweights from locking themselves in smoke-filled rooms and scheming for B2B dominance. If there's anything they've agreed on so far, it's that the exchanges must remain independent from the big companies backing them. Nearly all the major public exchanges are separate companies or joint ventures, with the backing companies owning a percentage of the new entity. The arrangement gives the owners a chance to make back their investment one day by spinning the exchange out as an IPO.

But for now, it is a tool to develop trust among the members themselves, but also among the suppliers and competitors they want to join the exchange.

For Covisint, the big auto industry exchange, time and urgency have helped erode the walls around each of the owners. "At the beginning, you couldn't have a meeting without a representative from each [Big Three automaker] being there," says Shankar Kiru, business development executive for Covisint. "But we quickly realized we weren't going to get anywhere operating that way." Meetings without quorums are now allowed, but Covisint still needs to maintain strict neutrality on the big issues. The relationship of the members is not exactly cozy, but for the notoriously competitive auto industry, it's a big step. "This is the first time since WWII that the auto industry has agreed on how to do things together," jokes Kiru.

In terms of impact on the industry, the Internet provides a cause to rally around and streamline the automakers' Byzantine supply chains. "Ford, GM and Chrysler all compete—but what they have in common is a passion to break through on the supply chain and streamline it," says Kiru. At least Ford, GM and Chrysler all do basically the same thing. About the only thing Albertson's and the other companies in the WWRE have in common is that they all sell stuff. That limits the WWRE's bulk buying power to commodity items such as paper and pens. So WWRE's Steele has already begun looking beyond auctions for his payback from the exchange. The first few auctions may bring lower prices, but the gains are going to bottom out quickly once everyone finds the cheapest paper and pens, says Steele. "Auctions allow buyers and sellers who didn't know each other existed to get together," he says. "But it can't sustain 20 percent price reductions each year because eventually you'd get to zero."

Poor utilization of power relationships and unpleasant past practices can also dilute the level of trust. Case 5 shows how the biggest challenge for Covisint is not technology or even process having to do with inter-organizational exchanges. It is developing a relationship of trust between the players. This requires an industry-level discourse that generates its own consensus. This process takes time and the implication is that organizations (both large and small) will hedge their bets and not necessarily put all their eggs in one basket. For instance, in the low trust environment, a small organization like Heyes-Lemmerz sees itself maintaining multiple information system architectures as required by different automakers. This is an instance of power-relationships at work. First tier suppliers in the auto industry—like Dana and Johnson Controls—are also building their own exchanges and, in doing so have, complicated the playing field. So, for the near term, both tier 1 and tier 2 suppliers will tend to manage an increased diversity of systems. This implies, that in the near-term, e-commerce enabled benefits will be marginal—at least in the auto industry.

Another instance of trust, or the lack of it, is seen in the now infamous case of Cisco's $2 billion write-off (Case 6). This case can now be considered a classic in terms of demonstrating how the effectiveness of the most sophisticated e-commerce framework can be undermined because of the non-synergistic interplay of power and trust between organizations.

Case 6. How Power, Trust and Technology Led to Cisco's Supply Chain Fiasco

Berinato (2001) reports how Solectron's forecasts were slowly diverging from Cisco. Solectron's were less optimistic, based on the general economy. There were meetings about it, but nothing was resolved about the growing disparity between what Cisco's outsourcers and customers thought was happening and what Cisco said was happening. "You try to talk it over. Sometimes it doesn't work. Can you really sit there and confront a customer and tell him he doesn't know what he's doing with his business? The numbers might suggest you should. At the same time," Shah (Solectron's CEO) laughs, trying to picture it, "I'd like to see someone in that conference room doing it." Demand forecasting is an art alchemized into a science. Reports from sales reps and inventory managers, based on anything from partners' data to conversations in an airport bar, are gathered along with actual sales data and historical trends and put into systems that use complex statistical algorithms to generate numbers. But there's no way for all the supply chain software to know what's in a sales rep's heart when he predicts a certain number of sales, Shah says. It's the same for allocation. If an inventory manager asks for 120 when he needs 100, the software cannot intuit, interpret or understand the manager's strategy. It sees 120; it believes 120; it reports 120. In this instance, the outsourced manufacturing model worked against Cisco because Cisco's partners were simply not as invested in delivering a loud wake-up call as an in-house supplier would have been. Shah also says it would have been presumptuous to confront a company like Cisco and tell it that it was wrong. When had Cisco ever been wrong? But now Shah thinks that over reliance on the forecasting technology led people to undervalue human judgment and intuition, and inhibited frank conversations among partners. On top of that, there's the possibility that despite what the publicity said, Cisco's supply chain was not quite as wired as was hyped. Cisco, Solectron and others do plenty of business with companies that still fax data. Some customers simply won't cater to the advanced infrastructure, making it harder to collect and aggregate information.

Cisco's case points to the situation where manufacturers of network devices for Cisco were caught in the position of acting as suppliers first and then as stakeholders in an extended enterprise. This implied that even if they perceived a problem in the forecasted numbers, it was not easy for them to challenge, or even question, Cisco primarily because Cisco was the client (and clients are never wrong) and secondly, it was difficult to question Cisco—a company that had done everything right—until then. The problem was more of managing agreements rather than disagreements—with the result being that everyone ended up being where no one wanted to be in the first place. This is identical to the Abilene Paradox (Harvey, 1974). It is important, from a strategy standpoint, therefore to ensure that trust is treated as a process and that complementary and matching processes are created within and across organizations that mitigate against lack of trust.

[10]Cisco's Pat Frey, Manager of Supply Chain Operations describes the problem of sharing information between supply chain partners when she says, "We've run into quite a bit of resistance. Lots of people just aren't ready to start sharing information on this level" (Barros et al., 1998). This is similar to the problem between Ford's suppliers and Ford. If the distribution channel doesn't trust the intentions of the manufacturer you can bet they will resist sharing their most valuable assets, i.e., customer intelligence.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 195