Teambuilding and the Stages of Team Development

Teambuilding and the Stages of Team Development

Effective leaders match their style and behavior to the situations they face. Hersey and Blanchard (1996) point out that when teams are new to the situation and do not know each other very well, it is better for the leader to be able to tell people what needs to be done and how to do it. As the team matures as a unit and gains experience in doing the tasks , the leader should shift to selling ideas about how to do things and to work together. Once the team becomes familiar with the work and each other, the leader participates with the team, identifying problems and options but ensuring that the input of team members and the leader is utilized in any decisions affecting activities. Ultimately, the leader delegates responsibility to the team to decide how to get the work done in a collaborative manner, while the leader skillfully provides the connection with the larger organization by clarifying expectations, gaining resources, and recognizing the team's accomplishments. Thus the level of maturity of a team determines which leadership style is most effective.

All teams tend to go through various stages as they develop. Perhaps the best-known model for these stages was developed by Tuckman and Jensen (1977), as follows :

-

Forming: Clarifying the task and getting the members acquainted

-

Storming: Encouraging the expression of different points of view in a constructive manner and resolving the natural competition for influence among the team members

-

Norming: Establishing the team's standards for performance and the unwritten rules that govern members' behaviors

-

Performing: Accomplishing the tasks and fulfilling the team's mission

-

Closing: Disbanding the team.

In reality, things are not quite that cut-and- dried , but the model does serve as a useful framework for determining the help teams may need as they mature. Whenever the organization provides a deadline for accomplishing a task, the team will attempt to jump to the Performing stage. The model lays out the kinds of things teambuilding sessions should facilitate to produce a team capable of delivering up to its maximum potential when performing.

Helping Teams Through the Forming Stage

If you are being asked to help launch a new team in your organization, you will need to identify the team's membership and its purpose. Chapter 4 will provide you with valuable tools, such as team chartering, to identify purpose, goals, responsibilities, procedures, and ground rules to get the team off on the right foot . As a leader, you need to provide a means for getting the team organized to accomplish the tasks it was formed to achieve. You need to help the team understand why it exists in your organization.

The other side of the Forming stage is recruiting and selecting the members of the team. You need to help identify people to handle the job responsibilities and to build respectful and trusting relationships with each other. If you have the opportunity to influence who will be on the team, you will want to ensure that the range of technical skills needed to accomplish the tasks is represented. In addition, thought should be given to which constituencies are likely to be affected by the work this team will be asked to do. To gain political clout and the subsequent commitment to implement the ideas generated by the team, representatives from these stakeholders could be included. Politics will always be involved to some extent in the selection of team members, especially on committees and task forces. Don't forget to include an examination of the interpersonal skills needed to help your team succeed. This is especially important if you are hiring new employees to form this team. If your organization is serious about using a team concept as a key strategy and structure for building a better company, then you need to include team skills as part of your selection procedures as you search for the "right" people to join the team. What talent, knowledge, and personal qualities are needed? What protocol and organizational politics should be kept in mind when selecting members for the team? Table 8 lists some things you should consider in the selection of team members.

| With the purpose of the team firmly in mind, the following guidelines can help you get the "right" people on the team. What talent, knowledge, and personal qualities are needed? What protocol and organizational politics should be considered ?

|

The first meeting of your new team should have both a task and a relationship component. The task component would involve having the members understand (or establish/negotiate) the team's charter. It would be useful to have a representative from senior management attend this portion of the meeting to further establish the importance of the team being formed. The establishment of a team charter will be covered thoroughly in chapter 4. The other half of this first team meeting should be dedicated to having the members get acquainted with each other. There are many ways to do this. You might consider having team members pair up and interview each other and then act as a "designated bragger" for their new teammate. This reduces the inhibition of having to say great things about oneself and it establishes that everyone needs to speak up at team meetings. I have found that even shy team members want to make sure they do not let their new-found friend down.

A more common practice is to have members introduce themselves to their teammates. It is useful to establish a document that captures the collective talents that exist on your team. It is motivating to see that you are part of a body that includes so much knowledge and talent. Here are a few questions to help inventory the talents of the team:

-

What knowledge bases exist on this team?

-

What skill bases exist on this team?

-

What knowledge and/or skill bases might be missing? To whom can we turn to fill in the gaps?

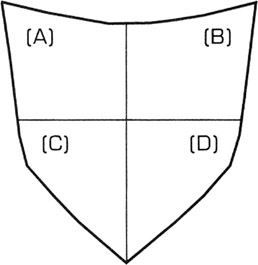

Exercise 11 provides another way for members to get to know each other. It asks each member to develop a personal "coat of arms" as a means of sharing personal information with others. Directions should be provided to team members in advance so that they can prepare their coat of arms and use the meeting time to present it to their new teammates. You can also make this a fun activity for everyone to do at the session itself. Bring in lots of magazines from which people can cut out pictures ”many people are inhibited about drawing pictures. Do what you can to produce a friendly, supportive atmosphere. Remember, the purpose of this exercise is for members to get acquainted, not to judge artistic talent.

| |

Personal "Coat of Arms"

The purpose of this exercise is to get team members to reveal information about who they are as a person in a fun and symbolic manner.

Directions for team members:

-

Draw a coat of arms divided into four sections as shown, enlarged to fill an 8 1/2 — 11 ³ sheet of paper. The sections could be designated in advance by the facilitator, or team members could be asked for their preferences.

Examples:

-

(A) key relationships, (B) work experience, (C) education, (D) values or personality

-

(A) past, (B) present, (C) short-term future, (D) long- term future

-

(A) skills, (B) knowledge, (C) personal qualities/values, (D) aspirations/hopes/dreams

You might also make up your own four sections.

-

-

Fill each portion with drawings, small pictures cut out of magazines, and a key word or two.

-

Present your personal coat of arms to the other participants and explain the symbolism behind the things you included.

-

Respond to questions from the other participants.

-

State what you learned about yourself and what you learned about the others who participated.

| |

Helping Teams Through the Storming Stage

It is natural for teams to experience some conflict. A major benefit of using a team approach is having differing points of view to consider. This leads to competition for influence. As a leader, you can help the team learn how to handle constructively the resulting arguments and discussions. You can help by letting the team know that conflict is natural. You can help by channeling members' competitive urges toward the accomplishment of the team goal instead of toward each other. The more specific the goals, the easier this will be. Training sessions for developing conflict resolution skills may be required. Chapter 7 provides material and tools for such sessions.

Helping Teams Through the Norming Stage

The best teams choose how they are going to conduct business. They have a methodology for how they will hold meetings, solve problems, make decisions, and go about their tasks. While there is no one best way to do any of these procedures, discussing and agreeing on an approach to them and then seeing that everyone on the team actually uses it helps build belief in the team. Trust is developed through actions, not words, so here is a chance to gain members' trust. Team members with a high need for achievement may be reluctant to count on the team to deliver. They may secretly feel, "If it is going to be, it is up to me." Later they may complain that others are not doing their fair share of the tasks. Perhaps the real problem is that the team does not have norms for how to conduct these procedures or standards for performance. Your job as leader is to help them establish these norms and standards, perhaps by

-

Updating the team charter

-

Sending team members to training sessions on problem solving, decision making, and running effective meetings, and then expecting them to practice what they learn in the sessions

-

Providing awareness and feedback about the processes that have already evolved.

Table 9 includes a list of team norms I have helped teams identify about themselves. Some they have wanted to keep and some they have decided to try to change.

|

|

Have your team use this list as well as its own observations to determine which norms describe how it operates. Many norms and procedures seem to materialize unconsciously. Your job is to help your team become conscious of them. Facilitate a discussion about whether the team wants to continue following the norms identified or to change them. What standards does your team want to live up to? How can members of the team monitor whether their behavior is living up to these standards? Help your team help itself.

Helping Teams Through the Performing Stage

Team members need to know the score. As a leader in a team environment, what can you do to help the team know whether it is accomplishing the goals and progressing according to plan? Many companies are providing boards near each team's work space with more information on productivity and quality than was traditionally provided to the workforce. What can you do to help team members comprehend the information provided? How can you help ensure that information is updated in a timely fashion? How can you remind members of the commitments they made during problem-solving efforts? The key to the leader's role during the Performing stage is letting members do their work and providing feedback on the team's progress against the expectations. Chapter 10 provides more detailed advice on the data that should be collected for evaluating the outcomes and processes of your team during the Performing stage.

Helping Teams Through the Closing Stage

Tuckman and Jensen's (1977) revised model of stages of group development suggests that there are common behavioral reactions to the realization that a team will soon be disbanded. When the team has completed its task, the leader can help bring about positive closure to the team's experience in a number of ways. The team should feel appreciated for its efforts and be recognized by management for the degree to which it has accomplished its tasks. Problem-solving teams will also want to feel assured that their ideas will be implemented. Perhaps most important, team members and the organization as a whole will benefit from spending time identifying the lessons learned, which could be used to improve future team efforts.

But you really shouldn't wait until the Closing stage to identify these lessons. Many organizations now insist on teams adhering to a system that regularly identifies lessons learned and makes those lessons available to other teams as well. The U.S. Army's procedure known as "after-action review" is now being copied by many business organizations (see table 10). The after-chapter reviews in this book are based on it. Establishing some sort of debriefing system will help your organization learn from the experience of its teams and make members feel that they are part of the system.

| After each significant event in a team's life, 15 “60 minutes should be dedicated to documenting and learning from the experience. The six questions listed below, modeled after the U.S. Army's approach, can be used to match the needs and opportunities presented by the team concept in your organization.

|

It should be noted that the Closing stage of a team's existence may produce changes in the behavior of some members as the time approaches to disband the team. Some members may experience separation anxiety. Others who have been relatively inactive may suddenly try to contribute ideas as they see the opportunity slipping away. Sometimes teams come to the point where they have solved those problems within their control but now see other problems they wish the organization would address. This may produce frustration. If members continue to meet and focus on what cannot be addressed, they may become angry or depressed. This is not conducive to the future success of the team concept. If you cannot get management to expand the scope of the team's charter, you may need to suggest disbanding the team. Again, the best you can do is provide a sense of genuine celebration for what has been accomplished and the opportunity to learn from the team's experience. Leaders sometimes have to help people experience the wisdom of letting go. Help them understand and address the things they can control and understand and let go of the things they cannot ”and feel the wisdom of knowing the difference between the two.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 137